Joe Biden

Joe Biden | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2021 | |

| 46th President of the United States | |

| Assumed office January 20, 2021 | |

| Vice President | Kamala Harris |

| Preceded by | Donald Trump |

| 47th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 2009 – January 20, 2017 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | Dick Cheney |

| Succeeded by | Mike Pence |

| United States Senator from Delaware | |

| In office January 3, 1973 – January 15, 2009 | |

| Preceded by | J. Caleb Boggs |

| Succeeded by | Ted Kaufman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. November 20, 1942 Scranton, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (1969–present) |

| Other political affiliations | Independent (before 1969) |

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Relatives | Biden family |

| Education | Archmere Academy |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | List of honors and awards |

| Signature |  |

| Website | |

Other offices

| |

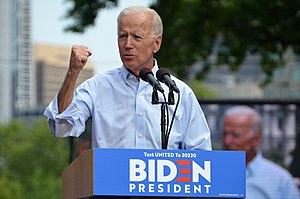

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. is an American politician, former vice president (2009–2017), and 46th President of the United States (2021–2024). Biden prevailed in the November 5, 2020 election against Donald Trump, making him the oldest person inaugurated as a U.S. president at age 78. During Biden's long political career, he represented Delaware in the Senate for over three decades, and chaired influential committees. He served two terms as vice president under Barrack Obama. Biden was known early on for his modest upbringing and understanding of working-class struggles, often referring to himself as "middle-class Joe", a term no longer befitting his net worth at around $8 million as vice president, rising to around $10 million in August 2023, after he became president.

President Biden made history again by appointing Ketanji Brown Jackson as the first Black woman to serve on the Supreme Court. He has signed significant legislation, such as the American Rescue Plan Act which was enacted to address the COVID-19 pandemic and recession; however, after a year into the plan, increasing inflation brought mixed reviews. Harvard professor Jason Furman, former economic advisor to Obama, said the plan was supposed to "create a success that would make people want to do more". In practice, the plan "contributed to inflation that made people want to do less." Inflation hit its highest rate in four decades at 7.9% under Biden, with approximately 2.5–3 percentage points attributed to the plan. Another notable challenge Biden faced during his administration was his chaotic withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan in 2021, which raised questions about his leadership and legacy.

In foreign policy, Biden rejoined the Paris Agreement on climate change and responded to the Russian invasion of Ukraine by imposing sanctions and providing aid to Ukraine. Concerns emerged over potential global conflicts, including tensions between Russia and Ukraine, as well as the conflict between Hamas and Israel, fueling fears of a broader conflict and possibly World War III.

Throughout his presidency, Biden's cognitive abilities have been scrutinized, with concerns raised about his verbal missteps and mental sharpness. A New York Times/Siena College poll indicated there were widespread doubts about his fitness for office, further highlighted by a special counsel report revealing memory limitations. Despite assertions from the White House, questions remain about Biden's suitability to be commander-in-chief.

Early life (1942–1965)

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. was born on November 20, 1942,[1] at St. Mary's Hospital in Scranton, Pennsylvania,[2] to Catherine Eugenia "Jean" Biden (née Finnegan) and Joseph Robinette Biden Sr.[3][4] The oldest child in a Catholic family, he has a sister, Valerie, and two brothers, Francis and James.[5] Jean was of Irish descent,[6][7][8] while Joseph Sr. had English, Irish, and French Huguenot ancestry.[9][10][8] Biden's paternal line has been traced to stonemason William Biden, who was born in 1789 in Westbourne, England, and emigrated to Maryland in the United States by 1820.[11]

Biden's father had been wealthy and the family purchased a home in the affluent Long Island suburb of Garden City in the fall of 1946,[12] but he suffered business setbacks around the time Biden was seven years old,[13][14][15] and for several years the family lived with Biden's maternal grandparents in Scranton.[16] Scranton fell into economic decline during the 1950s and Biden's father could not find steady work.[17] Beginning in 1953 when Biden was ten,[18] the family lived in an apartment in Claymont, Delaware, before moving to a house in nearby Mayfield.[19][20][14][16] Biden Sr. later became a successful used-car salesman, maintaining the family in a middle-class lifestyle.[16][17][21]

At Archmere Academy in Claymont,[22] Biden played baseball and was a standout halfback and wide receiver on the high school football team.[16][23] Though a poor student, he was class president in his junior and senior years.[24][25] He graduated in 1961.[24] At the University of Delaware in Newark, Biden briefly played freshman football,[26][27] and, as an unexceptional student,[28] earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1965 with a double major in history and political science and a minor in English.[29][30]

Biden has a stutter, which has improved since his early twenties.[31] He says he reduced it by reciting poetry before a mirror,[25][32] but some observers suggested it affected his performance in the 2020 Democratic Party presidential debates.[33][34][35]

Marriages, law school, and early career (1966–1973)

On August 27, 1966, Biden married Neilia Hunter (1942–1972), a student at Syracuse University,[29] after overcoming her parents' reluctance for her to wed a Roman Catholic. Their wedding was held in a Catholic church in Skaneateles, New York.[36] They had three children: Joseph R. "Beau" Biden III (1969–2015), Robert Hunter Biden (born 1970), and Naomi Christina "Amy" Biden (1971–1972).[29]

In 1968, Biden earned a Juris Doctor from Syracuse University College of Law, ranked 76th in his class of 85, after failing a course due to an acknowledged "mistake" when he plagiarized a law review article for a paper he wrote in his first year at law school.[28] He was admitted to the Delaware bar in 1969.[1]

Biden had not openly supported or opposed the Vietnam War until he ran for Senate and opposed Nixon's conduct of the war.[37] While studying at the University of Delaware and Syracuse University, Biden obtained five student draft deferments, at a time when most draftees were sent to the Vietnam War. In 1968, based on a physical examination, he was given a conditional medical deferment; in 2008, a spokesperson for Biden said his having had "asthma as a teenager" was the reason for the deferment.[38]

In 1968, Biden clerked at a Wilmington law firm headed by prominent local Republican William Prickett and, he later said, "thought of myself as a Republican".[39][40] He disliked incumbent Democratic Delaware governor Charles L. Terry's conservative racial politics and supported a more liberal Republican, Russell W. Peterson, who defeated Terry in 1968.[39] Biden was recruited by local Republicans but registered as an Independent because of his distaste for Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon.[39]

In 1969, Biden practiced law, first as a public defender and then at a firm headed by a locally active Democrat[41][39] who named him to the Democratic Forum, a group trying to reform and revitalize the state party;[42] Biden subsequently reregistered as a Democrat.[39] He and another attorney also formed a law firm.[41] Corporate law, however, did not appeal to him, and criminal law did not pay well.[16] He supplemented his income by managing properties.[43]

In 1970, Biden ran for the 4th district seat on the New Castle County Council on a liberal platform that included support for public housing in the suburbs.[44][41][45] The seat had been held by Republican Henry R. Folsom, who was running in the 5th District following a reapportionment of council districts.[46][47][48] Biden won the general election by defeating Republican Lawrence T. Messick, and took office on January 5, 1971.[49][50] He served until January 1, 1973, and was succeeded by Democrat Francis R. Swift.[51][52][53][54] During his time on the county council, Biden opposed large highway projects, which he argued might disrupt Wilmington neighborhoods.[55]

1972 U.S. Senate campaign in Delaware

In 1972, Biden defeated Republican incumbent J. Caleb Boggs to become the junior U.S. senator from Delaware. He was the only Democrat willing to challenge Boggs, and with minimal campaign funds, he was given no chance of winning.[41][16] A few months before the election, Biden trailed Boggs by almost thirty percentage points,[41] but won with 50.5 percent of the vote. He was 29 years old at the time, but reached the constitutionally required age of 30 before he was sworn in as Senator.[56]

Death of wife and daughter

On December 18, 1972, a few weeks after Biden was elected senator, his wife Neilia and one-year-old daughter Naomi were killed in an automobile accident while Christmas shopping in Hockessin, Delaware.[29][57] Neilia's station wagon was hit by a semi-trailer truck as she pulled out from an intersection. Their sons Beau (aged 3) and Hunter (aged 2) were taken to the hospital in fair condition, Beau with a broken leg and other wounds and Hunter with a minor skull fracture and other head injuries.[58] Biden considered resigning to care for them,[21] but Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield persuaded him not to.[59]

Years later, Biden said he believed the truck driver had been drinking before the crash, but was never charged, and the driver's family said the deaths haunted him until he died in 1999.[60] Biden later apologized to the driver's family.[61][62][63][64][65] The accident filled Biden with anger and religious doubt. He wrote that he "felt God had played a horrible trick" on him,[66] and he had trouble focusing on work.[67][68]

Second marriage, and death of his eldest son

Biden met teacher Jill Tracy Jacobs in 1975 on a blind date.[69] They married at the United Nations chapel in New York on June 17, 1977.[70][71] They spent their honeymoon at Lake Balaton in the Hungarian People's Republic.[72][73] Biden credits her with the renewal of his interest in politics and life.[74] They are Roman Catholics and attend Mass at St. Joseph's on the Brandywine in Greenville, Delaware.[75]

Their daughter Ashley Biden (born 1981)[29] is a social worker, and is married to physician Howard Krein.[76] Beau Biden became an Army Judge Advocate in Iraq, and later Delaware Attorney General[77] before his death in 2015 from glioblastoma, a type of brain cancer.[78][79] Beau was an Iraq War veteran, and was awarded a Bronze Star.[80] Biden's second child, Hunter Biden, has a law degree from Yale, has struggled with a long term addiction to crack cocaine and alcohol, and has been involved in various questionable business ventures.[81]

Brain surgeries

In February 1988, after several episodes of increasingly severe neck pain, Biden was taken by ambulance to Walter Reed Army Medical Center for surgery to correct a leaking intracranial berry aneurysm.[82][83] While recuperating, he suffered a pulmonary embolism, a serious complication.[83] After a second aneurysm was surgically repaired in May,[83][84] Biden's recuperation kept him away from the Senate for seven months.[85]

Teaching

From 1991 to 2008, as an adjunct professor, Biden co-taught a seminar on constitutional law at Widener University School of Law.[86][87] The seminar often had a waiting list. Biden sometimes flew back from overseas to teach the class.[88][89][90][91]

Biden family investigation

Both President Biden and his son Hunter have been under investigation by the DOJ and Congress as a result of Hunter's controversial laptop, which is reported to contain a number of email disclosures and nude photographs. Other issues include Hunter's addiction to crack cocaine and alcohol, illegal gun possession, family business dealings, and apparent influence peddling with communist China. Hunter also landed a high paying position on the board of Burisma, a Ukrainian energy company that was under investigation for corruption.[92] Hunter's business dealings are intertwined with his influence peddling, and may well have cast an irreparable shadow over his father's legacy, but not without help from President Biden himself. Dating back to October 22, 2020, Joe Biden lied about his son making money in China, and referred to then President Trump as “the only guy who made money from China".[93] In December 2023, President Biden faced accusations of dishonesty after previously denying any interactions with his family's foreign business associates. Evidence from bank records and witness testimony presented by the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability contradicted his statement, revealing numerous instances where Biden engaged with his son Hunter Biden's foreign business contacts. These interactions included phone conversations, attendance at dinners and meetings, and coffee meetings with individuals such as Russian and Kazakhstani oligarchs, a Burisma executive, and Chinese nationals who contributed substantial sums to his son's ventures.[94][95]

U.S. Senate (1973–2009)

During his early Senate years, Biden prioritized consumer protection, environmental issues, and government accountability, while aligning as liberal on civil rights, senior citizens' concerns, and healthcare, yet conservative on matters such as abortion and military conscription.[96][97] He also gained prominence for his vocal criticism of the Reagan administration's support for apartheid-era South Africa, notably excoriating Secretary of State George Shultz during a Senate hearing.[39]

Elected to the Senate in 1972, Biden secured reelection in subsequent years with consistent support, maintaining about 60% of the vote,[98] initially serving alongside William Roth until Roth's defeat in 2000.[99] Biden's early mentor in the Senate was Robert Byrd, although Byrd's prior affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan is noted, Biden eulogized him in 2010 as a "mentor" and "dear friend."[100][101] By 2022, Biden ranked as the 19th-longest-serving senator in U.S. history.[102]

Presidential campaigns of 1988 and 2008

1988 campaign

Biden formally declared his candidacy for the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination on June 9, 1987.[103] He was considered a strong candidate because of his moderate image, his speaking ability, his high profile as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee at the upcoming Robert Bork Supreme Court nomination hearings, and his appeal to Baby Boomers; he would have been the second-youngest person elected president, after John F. Kennedy.[39][104][105] He raised more in the first quarter of 1987 than any other candidate.[104][105]

Plagiarism issues

By August his campaign's messaging had become confused due to staff rivalries,[106] and in September, it was discovered that he plagiarized a speech by British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock.[107] Biden's speech had similar lines about being the first person in his family to attend university. Biden had credited Kinnock with the formulation on previous occasions,[108][109] but did not on two occasions in late August.[110]: 230–232 [109] Kinnock himself was more forgiving; the two men met in 1988, forming an enduring friendship.[111] Biden had also used passages from a 1967 speech by Robert F. Kennedy (for which his aides took blame) and a short phrase from John F. Kennedy's inaugural address; two years earlier he had used a 1976 passage by Hubert Humphrey.[112] Biden responded that politicians often borrow from one another without giving credit, and that one of his rivals for the nomination, Jesse Jackson, had called him to point out that he (Jackson) had used the same material by Humphrey that Biden had used.[21][28]

Biden has also lied about his early life: that he had earned three degrees in college, that he attended law school on a full scholarship, that he had graduated in the top half of his class,[113][114] and that he had marched in the civil rights movement.[115] The limited amount of other news about the presidential race amplified these disclosures[116] and on September 23, 1987, Biden withdrew his candidacy, saying it had been overrun by "the exaggerated shadow" of his past mistakes.[117]

2008 campaign

After exploring the possibility of a run in several previous cycles, in January 2007, Biden declared his candidacy in the 2008 elections.[98][118][119] During his campaign, Biden focused on the Iraq War, his record as chairman of major Senate committees, and his foreign-policy experience. In mid-2007, Biden stressed his foreign policy expertise compared to Obama's.[120] Biden was noted for his one-liners during the campaign; in one debate he said of Republican candidate Rudy Giuliani: "There's only three things he mentions in a sentence: a noun, and a verb and 9/11."[121]

In the first contest on January 3, 2008, Biden placed fifth in the Iowa caucuses, garnering slightly less than one percent of the state delegates.[122] He withdrew from the race that evening.[123] Despite the Biden campaign's inability to raise adequate campaign funds and draw people to its rallies,[124] their efforts still managed to raise Biden's stature in the political world.[125]: 336 In particular, it changed the relationship between Biden and Obama. Although they had served together on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, they had not been close: Biden resented Obama's quick rise to political stardom,[126][127] while Obama viewed Biden as garrulous and patronizing.[125]: 28, 337–338 Having gotten to know each other during 2007, Obama appreciated Biden's campaign style and appeal to working-class voters, and Biden said he became convinced Obama was "the real deal".[127][125]: 28, 337–338

2008 vice-presidential campaign

Biden's vice-presidential campaigning gained little media attention, as the press devoted far more coverage to the Republican nominee, Alaska Governor Sarah Palin.[128][129] Under instructions from the campaign, Biden kept his speeches succinct and tried to avoid offhand remarks, such as one he made about Obama's being tested by a foreign power soon after taking office, which had attracted negative attention.[130][131] Privately, Biden's remarks frustrated Obama. "How many times is Biden gonna say something stupid?" he asked.[125]: 411–414, 419 Obama campaign staffers called Biden's blunders "Joe bombs" and kept Biden uninformed about strategy discussions, which in turn irked Biden.[132] Relations between the two campaigns became strained for a month, until Biden apologized on a call to Obama and the two built a stronger partnership.[125]: 411–414 Publicly, Obama strategist David Axelrod said Biden's high popularity ratings had outweighed any unexpected comments.[133]

On November 4, 2008, Obama and Biden were elected with 53% of the popular vote and 365 electoral votes to McCain–Palin's 173.[134][135][136]

At the same time Biden was running for vice president he was also running for reelection to the Senate,[137] as permitted by Delaware law.[98] On November 4, he was reelected to the Senate, defeating Republican Christine O'Donnell.[138] Having won both races, Biden made a point of waiting to resign from the Senate until he was sworn in for his seventh term on January 6, 2009.[139] Biden cast his last Senate vote on January 15, supporting the release of the second $350 billion for the Troubled Asset Relief Program,[140] and resigned from the Senate later that day.[n 2]

Vice presidency (2009–2017)

During his tenure as Vice President from 2009 to 2017 under President Barack Obama, Joe Biden navigated a multitude of domestic and international challenges. Biden played a pivotal role in shaping the Obama administration's response, which included the passage of the historic Affordable Care Act (ACA), which was aimed at expanding access to healthcare for millions of Americans but with little regard to increasing costs for middle America. A recent study by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) revealed significant increases in premiums for ACA marketplace plans. In 2023, the average annual health insurance premiums reached $8,435 for single coverage and $23,968 for family coverage, marking a 7% rise from the previous year alone. Notably, family premiums have surged by 22% since 2018 and a staggering 47% since 2013. According to healthcare.gov, employer-sponsored coverage is considered "affordable" in 2023 if it constitutes less than 9.12% of household income.[144]

Throughout his vice presidency, Biden was a staunch advocate for progressive policies, championing initiatives to combat climate change and promote renewable energy sources. His leadership on these fronts helped set the stage for future efforts to address pressing environmental issues. Biden's tenure as Vice President was not without criticism, particularly regarding certain foreign policy decisions. The withdrawal of American troops from Iraq and the administration's response to the escalating civil war in Syria faced scrutiny from both domestic and international observers. Additionally, questions arose about the handling of classified documents during the transition out of his vice presidential office in 2017, leading to a special counsel investigation by Robert K. Hur. The final report stated that Biden had retained and disclosed classified material after leaving the vice presidency in 2017. However, the report concluded that no criminal charges were warranted. Hur criticized Biden for sharing classified content from notebooks with a ghostwriter for his memoir, Promise Me, Dad. Although the evidence did not establish Biden's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, some of the findings created a political crisis for the White House. Hur portrayed Biden as having a poor memory during interviews, citing his age and suggesting it would be difficult to convict a former president well into his 80s of a felony requiring a mental state of willfulness.[145]

Biden never cast a tie-breaking vote in the Senate, making him the longest-serving vice president with this distinction.[146]

Role in the 2016 presidential campaign

As of September 11, 2015[update], Biden was still uncertain about running. He felt his son's recent death had largely drained his emotional energy, and said, "nobody has a right ... to seek that office unless they're willing to give it 110% of who they are."[147] On October 21, speaking from a podium in the Rose Garden with his wife and Obama by his side, Biden announced his decision not to run for president in 2016.[148][149][150] In January 2016, Biden affirmed that it was the right decision, but admitted to regretting not running for president "every day".[151]

After Obama endorsed Hillary Clinton on June 9, 2016, Biden endorsed her later that day.[152] Throughout the 2016 election, Biden strongly criticized Clinton's opponent, Donald Trump, in often colorful terms.[153][154]

Subsequent activities (2017–2019)

After leaving the vice presidency, Biden became an honorary professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Titled the "Benjamin Franklin Presidential Practice Professor", Biden led panel discussions on history and politics and developed the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement.[155] He also continued to lead efforts to find treatments for cancer.[156] In 2017, he wrote a memoir, Promise Me, Dad, and went on a book tour.[157] Biden earned $15.6 million from 2017 to 2018.[158] In 2018, he gave a eulogy for Senator John McCain, praising McCain's embrace of American ideals and bipartisan friendships.[159] Biden was targeted by two pipe bombs that were mailed to him during the October 2018 mail bombing attempts, which targeted democratic lawmakers and critics of then President Trump. One device was noticed and identified as a bomb in New Castle, Delaware, due to insufficient postage and subsequent examination, while another was found at a Wilmington, Delaware, postal facility and intercepted there.[160] The devices were later found to have been intentionally designed to not detonate.[161]

Biden remained in the public eye, endorsing candidates while continuing to comment on politics, climate change, and the presidency of Donald Trump.[162]Greenwood, Max (May 31, 2017). "Biden: Paris deal 'best way to protect' US leadership". The Hill. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2021.</ref> He also continued to speak out in favor of LGBT rights, continuing advocacy on an issue he had become more closely associated with during his vice presidency.[163] In 2019, Biden criticized Brunei for its intention to implement Islamic laws that would allow death by stoning for adultery and homosexuality, calling this "appalling and immoral" and saying, "There is no excuse—not culture, not tradition—for this kind of hate and inhumanity."[164] By 2019, Biden and his wife reported that their assets had increased to[clarification needed] between $2.2 million and $8 million from speaking engagements and a contract to write a set of books.[165]

2020 presidential campaign

A political action committee known as Time for Biden was formed in January 2018, seeking Biden's entry into the race.[166] He finally launched his campaign on April 25, 2019,[167] saying he was prompted to run, among other reasons, by his "sense of duty."[168]

Campaign

Throughout 2019 and into 2020, Joe Biden faced a series of controversies and challenges, including allegations of inappropriate physical contact from multiple women, which he acknowledged and pledged to address.[169][170] Meanwhile, he navigated political scrutiny over his role in Ukraine, with accusations from President Trump and allies regarding his son Hunter Biden's involvement with Burisma Holdings. Despite investigations by Senate committees, no evidence of wrongdoing by Joe Biden was found at the time. Additionally, a resurgence of allegations against Hunter Biden in 2023, prompted by a released FBI document, reignited debate over the Bidens' dealings in Ukraine.[171]

None of the allegations against Biden were adequately covered by mainstream media for various reasons.[172][173] Whenever coverage was published in mainstream outlets, some journalists labeled the allegations as conspiracy theories, or dismissed them for lack of evidence, or wrote that the actions by the Bidens were not a big deal as were the allegations against Trump.[174] On the other hand, historians, fact-checkers, and various academic reviewers of media's coverage of Trump vs Biden, such as the Columbia Journalism Review and Pew Research, have provided some rather unflattering reviews of mainstream media's coverage.[175][176] Biden maintained a lead in national polls for the Democratic nomination, though he faced setbacks in early primary contests. However, strong showings in key states, particularly in South Carolina and on Super Tuesday, propelled him to front-runner status. By April 2020, with Bernie Sanders suspending his campaign, Biden secured the Democratic Party's presidential nomination, endorsed by Sanders and former President Barack Obama. He committed to selecting a woman as his running mate, eventually choosing Kamala Harris. In August 2020, Biden was officially nominated as the Democratic Party's candidate for president in the 2020 election at the Democratic National Convention.[177]

Election and Presidential transition

Biden prevailed in the 2020 United States presidential election against incumbent Donald Trump, and became the 46th president of the United States. After the election, reports of voter fraud with scant evidence to support it had been circulating among Trump supporters and his administration. Several court cases were filed in swing states questioning the outcome of the election. Senator Ted Cruz along with several others in congress said they would reject the certification of the Electoral College votes if an emergency audit is not conducted. Trump and many others were convinced the election had been "stolen", and demanded an investigation.[178]

On November 24, 2020, President Trump announced his administration's readiness to cooperate with President-elect Joe Biden's transition to the White House, marking the end of a delay that had faced criticism from both parties as his attempts to contest the election outcome faltered. Emily Murphy, head of the General Services Administration, who had delayed the transition for over two weeks citing election result uncertainties, also declared that her agency would provide Biden with federal resources necessary for a smooth transfer of power. Trump stated that he had instructed his aides to assist in the transition process as approved by the GSA, while reiterating his commitment to pursuing legal avenues to challenge the election outcome. He expressed confidence in prevailing but emphasized the importance of prioritizing the nation's interests by facilitating the initial transition protocols.[179]

On January 6, 2021, members of the House and Senate gathered in the House Chamber of the White House to count the official votes of the Electoral College, which formally ends the vote naming Joe Biden president. Several Republican Senators were prepared to challenge the vote, and call for investigations into unproven allegations of voter fraud and various other wrongdoings in swing states.[180]. That same day, Trump and thousands of his supporters attended his Save America rally held at The Ellipse, also referred to as President's Park South, a 52-acre (21 ha) park south located south of the White House,and north of Constitution Avenue. When the rally ended, protestors marched to the Capitol, saying, "We will never give up. We will never concede. It doesn't happen. You don't concede when there's theft involved."[181] Many others were already at the Capitol protesting peacefully, wanting their voices heard as to their concerns over what so many Americans believed was a stolen election. attacked the Capitol. During the insurrection at the Capitol, Biden addressed the nation, calling the events "an unprecedented assault unlike anything we've seen in modern times." He specifically called on Trump to "go on national television now to fulfill his oath and defend the Constitution and demand an end to this siege", adding, "it must end now."[182][183] After the Capitol was cleared, Congress resumed its joint session and officially certified the election results with Pence declaring Biden and Harris the winners.[184]

Presidency (2021–present)

2021

In his first two days as president, Biden signed 17 executive orders. By his third day, orders had included rejoining the Paris Climate Agreement, ending the state of national emergency at the border with Mexico, directing the government to rejoin the World Health Organization, face mask requirements on federal property, measures to combat hunger in the United States,[185][186][187][188] and revoking permits for the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline.[189][190][191] In his first two weeks in office, Biden signed more executive orders than any other president since Franklin D. Roosevelt had in their first month in office.[192]

Other significant legislation Biden signed into action included the American Rescue Plan Act to address the COVID-19 pandemic and recession; however, after the first year into the plan, it brought mixed reviews. Critics argue that Biden's stimulus policies have inadvertently fueled inflation, hindering Democratic efforts to enact significant societal changes, such as expanded education programs and subsidized childcare. Harvard professor Jason Furman, once an economic advisor to former President Obama, suggests that while the intention was to spur further action, the result has been counterproductive, contributing to a 7.9% inflation rate, the highest in four decades. Furman estimates that the rescue plan responsible for this inflation surge accounts for about 2.5 percentage points, while Michael Strain of the American Enterprise Institute suggests a higher figure of 3 percentage points.[193]

In the first eight months of his presidency, Morning Consult polling showed Biden's approval rating above 50%. A Gallup Poll showed that during his first year in office, his approval ratings started relatively strong at 57%, but had dropped to 43% by September. A January 2022 Gallup poll shows it as 40% after his Afghanastan withdrawal.[194] Other factors contributing to the decline include increasing hospitalizations from the Delta variant, high inflation and gas prices, disarray within the Democratic Party, and a general decline in popularity customary in politics.[195][196][197][198]

2022

In early 2022, Biden made efforts to change his public image after entering the year with low approval ratings due to inflation and high gas prices, which continued to fall to approximately 40% in aggregated polls by February.[199][200][201] He began the year by endorsing a change to the Senate filibuster to allow for the passing of the Freedom to Vote Act and John Lewis Voting Rights Act, on both of which the Senate had failed to invoke cloture.[202] The rules change failed when two Democratic senators, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, joined Senate Republicans in opposing it.[203]

COVID-19 diagnosis

On July 21, 2022, Biden tested positive for COVID-19 with reportedly mild symptoms.[204] According to the White House, he was treated with Paxlovid.[205] He worked in isolation in the White House for five days[206] and returned to isolation when he tested positive again on July 30.[207]

2022 election

On September 2, 2022, in a nationally broadcast Philadelphia speech, Biden called for a "battle for the soul of the nation." Off camera he called active Trump supporters "semi-fascists," which Republican commentators denounced.[208][209][210]

2023

Fewer Americans now see President Joe Biden as having several positive qualities as compared to what they believed in 2020. The biggest drop is in the belief that Biden can effectively manage the government, with decreases of at least six percentage points across the board. Meanwhile, perceptions of Donald Trump, who's likely to challenge Biden in 2024, haven't really shifted much. This suggests that many still see Trump as a strong leader, especially when compared to Biden's recent decline in public perception.[211]

Pew Research

In general, 62% of Americans hold an unfavorable opinion of Biden, which closely mirrors the 60% of Americans who perceive Trump negatively. Regarding Biden, line charts illustrate that the American populace regards both Biden and Trump less favorably than favorably. Although Biden's favorability ratings have remained relatively stable over the past year, they have become more negative compared to 2022. This change is primarily observed within his own party: in July 2022, 75% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning individuals viewed him positively, whereas today, positive views are at 67%. Republicans' unfavorable opinions of Biden have remained consistent during this period. Presently, 94% express an unfavorable view of him.[212]

Political positions

Biden is considered a moderate Democrat[213] and a centrist.[214][215] Throughout his long career, his positions have been aligned with the center of the Democratic Party.[216] In 2022, journalist Sasha Issenberg wrote that Biden's "most valuable political skill" was "an innate compass for the ever-shifting mainstream of the Democratic party."[217] He has a lifetime liberal 72% score from the Americans for Democratic Action through 2004, while the American Conservative Union gave him a lifetime conservative rating of 13% through 2008.[218]

Reputation

Biden was consistently ranked one of the least wealthy members of the Senate,[219][220][221] which he attributed to his having been elected young.[222] Feeling that less-wealthy public officials may be tempted to accept contributions in exchange for political favors, he proposed campaign finance reform measures during his first term. As of November 2009[update], Biden's net worth was $27,012.[223] By November 2020[update], the Bidens were worth $9 million, largely due to sales of Biden's books and speaking fees after his vice presidency.[224][225][226][227]

The political writer Howard Fineman has written, "Biden is not an academic, he's not a theoretical thinker, he's a great street pol. He comes from a long line of working people in Scranton—auto salesmen, car dealers, people who know how to make a sale. He has that great Irish gift."[43] Political columnist David S. Broder wrote that Biden has grown over time: "He responds to real people—that's been consistent throughout. And his ability to understand himself and deal with other politicians has gotten much much better."[43] Journalist James Traub has written that "Biden is the kind of fundamentally happy person who can be as generous toward others as he is to himself."[126]

In recent years, especially after the 2015 death of his elder son Beau, Biden has been noted for his empathetic nature and ability to communicate about grief.[228][229] In 2020, CNN wrote that his presidential campaign aimed to make him "healer-in-chief", while The New York Times described his extensive history of being called upon to give eulogies.[230]

Journalist and TV anchor Wolf Blitzer has described Biden as loquacious.[231] He often deviates from prepared remarks[232] and sometimes "puts his foot in his mouth."[233][128][234][235] The New York Times wrote that Biden's "weak filters make him capable of blurting out pretty much anything."[128] In 2018, Biden called himself "a gaffe machine".[236] Some of his gaffes have been characterized as racially insensitive.[237][238][239][240]

According to The New York Times, Biden often embellishes elements of his life to create a exaggerated political personality. His exaggerations include being an active civil rights activist who was repeatedly arrested during protests. Biden has also claimed to have been an excellent student who earned three different degrees. During a visit to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Fiona, he said he had been "raised in the Puerto Rican community at home, politically", even though Puerto Rico is not mentioned in his biographies. The Times wrote, "Mr. Biden's folksiness can veer into folklore, with dates that don't quite add up and details that are exaggerated or wrong, the factual edges shaved off to make them more powerful for audiences."[241]

Publications

Books

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr.; Helms, Jesse (April 1, 2000). Hague Convention on International Child Abduction: Applicable Law and Institutional Framework Within Certain Convention Countries Report to the Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7567-2250-0.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (July 8, 2001). Putin Administration's Policies toward Non-Russian Regions of the Russian Federation: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-7567-2624-9.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (July 24, 2001). Administration's Missile Defense Program and the ABM Treaty: Hearing Before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-7567-1959-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (September 5, 2001). Threat of Bioterrorism and the Spread of Infectious Diseases: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-7567-2625-6.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (February 12, 2002). Examining The Theft Of American Intellectual Property At Home And Abroad: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-7567-4177-8.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (February 14, 2002). Halting the Spread of HIV/AIDS: Future Efforts in the U.S. Bilateral & Multilateral Response: Hearings before the Comm. on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7567-3454-1.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (February 27, 2002). How Do We Promote Democratization, Poverty Alleviation, and Human Rights to Build a More Secure Future: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-7567-2478-8.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (August 1, 2002). Hearings to Examine Threats, Responses, and Regional Considerations Surrounding Iraq: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-7567-2823-6.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (January 1, 2003). International Campaign Against Terrorism: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7567-3041-3.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (January 1, 2003). Political Future of Afghanistan: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7567-3039-0.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (September 1, 2003). Strategies for Homeland Defense: A Compilation by the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7567-2623-2.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (July 31, 2007). Promises to Keep. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6536-3. Also paperback edition, Random House 2008, ISBN 978-0-8129-7621-2.

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (November 14, 2017). Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose. Flatiron Books. ISBN 978-1-250-17167-2.

Book contributions

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (2005). "Foreword". In Nicholson, William C. (ed.). Homeland Security Law and Policy. C. C Thomas. ISBN 978-0-398-07583-5.

- Biden, Joseph R., Jr. (2009). "Foreword". In Hayman, Robert L., Jr.; Leland, Ware (eds.). Choosing Equality: Essays and Narratives on the Desegregation Experience. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-03433-1.

Pamphlets

- Biden, Joseph R., Jr., and Les Aspin, William Louis Dickinson, Brent Scowcroft (1982). Arms Sales: A Useful Foreign Policy Tool? American Enterprise Institute. AEI Forum 56. Moderated by John Charles Daly.

Articles

- Biden, Joseph R. Jr.; Purev-Ochir, Miga (Spring 2015). "U.S.-Russian Relations in a Post-Cold War World: A Strategic Vision: Mapping a Future for U.S.-Russian Relations". Harvard International Review. 36 (3): 72–76. JSTOR 43649299.

See also

Notes

- ^ Biden held the chairmanship from January 3 to 20, then was succeeded by Jesse Helms until June 6, and thereafter held the position until 2003.

- ^ Delaware's Democratic governor, Ruth Ann Minner, announced on November 24, 2008, that she would appoint Biden's longtime senior adviser Ted Kaufman to succeed Biden in the Senate.[141] Kaufman said he would serve only two years, until Delaware's special Senate election in 2010.[141] Biden's son Beau ruled himself out of the 2008 selection process due to his impending tour in Iraq with the Delaware Army National Guard.[142] He was a possible candidate for the 2010 special election, but in early 2010 said he would not run for the seat.[143]

References

Citations

- ^ a b United States Congress. "Joseph R. Biden (id: b000444)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ Witcover (2010), p. 5.

- ^ Chase, Randall (January 9, 2010). "Vice President Biden's mother, Jean, dies at 92". WITN-TV. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Smolenyak, Megan (September 3, 2002). "Joseph Biden Sr., 86, father of the senator". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Witcover (2010), p. 9.

- ^ Smolenyak, Megan (July 2, 2012). "Joe Biden's Irish Roots". HuffPost. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ "Number two Biden has a history over Irish debate". The Belfast Telegraph. November 9, 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Witcover (2010), p. 8.

- ^ "French town's historic links to Joe Biden's inauguration". Connexionfrance.com. January 22, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Smolenyak, Megan (April–May 2013). "Joey From Scranton—VP Biden's Irish Roots". Irish America. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Nevett, Joshua (June 12, 2021). "Joe Biden: Unearthing the president's unsung English roots". BBC News. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Entous, Adam (August 15, 2022). "The Untold History of the Biden Family". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ Russell, Katie (January 8, 2021). "Joe Biden's family tree: how tragedy shaped the US president-elect". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Biden, Joe (2008). Promises to Keep: On Life and Politics. Random House. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-8129-7621-2.

- ^ Witcover (2010), pp. 7-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Broder, John M. (October 23, 2008). "Father's Tough Life an Inspiration for Biden". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2008.

- ^ a b Rubinkam, Michael (August 27, 2008). "Biden's Scranton childhood left lasting impression". Fox News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ Farzan, Antonia Noori (May 21, 2019). "Joe Biden, who left Scranton at 10, 'deserted' Pennsylvania". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Jennifer (January 20, 2021). "Joe Biden's houses". Homes and Gardens. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ Newman, Meredith (June 24, 2019). "How Joe Biden went from 'Stutterhead' to senior class president". News Journal. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c Almanac of American Politics 2008, p. 364.

- ^ Witcover (2010), pp. 27, 32.

- ^ Frank, Martin (September 28, 2008). "Biden was the stuttering kid who wanted the ball". The News Journal. p. D.1. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013.

- ^ a b Witcover (2010), pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Taylor (1990), p. 99.

- ^ Biden, Promises to Keep, pp. 27, 32–33.

- ^ Montanaro, Domenico. "Fact Check: Biden's Too Tall Football Tale". NBC News. Archived from the original on December 21, 2012.

- ^ a b c Dionne, E. J. Jr. (September 18, 1987). "Biden Admits Plagiarism in School But Says It Was Not 'Malevolent'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "A timeline of U.S. Sen. Joe Biden's life and career". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. August 23, 2008. Archived from the original on September 25, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ^ Taylor (1990), p. 98.

- ^ Biden, Joseph R. Jr. (July 9, 2009). "Letter to National Stuttering Association chairman" (PDF). National Stuttering Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ Hook, Janet (September 16, 2019). "Joe Biden's childhood struggle with a stutter: How he overcame it and how it shaped him". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Hendrickson, John (January–February 2020). "What Joe Biden Can't Bring Himself to Say". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ Bailey, Isaac J. (March 11, 2020). "Is Biden's Stutter Being Mistaken for "Cognitive Decline"?". Nieman Reports. Cambridge, MA: Nieman Foundation for Journalism. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Carlisle, Madeleine (December 20, 2019). "Sarah Huckabee Sanders Apologizes To Joe Biden After Mocking Debate Response on Stuttering". Time. New York, NY. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Biden, Promises to Keep, pp. 32, 36–37.

- ^ Witcover (2010), pp. 50, 75.

- ^ Caldera, Camille (September 16, 2020). "Fact check: Biden, like Trump, received multiple draft deferments from Vietnam". USA Today. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Leubsdorf, Carl P. (September 6, 1987). "Biden Keeps Sights Set On White House". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021. Reprinted in "Lifelong ambition led Joe Biden to Senate, White House aspirations". The Dallas Morning News. August 23, 2008. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008.

- ^ Barrett, Laurence I. (June 22, 1987). "Campaign Portrait, Joe Biden: Orator for the Next Generation". Time. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Current Biography Yearbook 1987, p. 43.

- ^ Witcover (2010), p. 86.

- ^ a b c Palmer, Nancy Doyle (February 1, 2009). "Joe Biden: 'Everyone Calls Me Joe'". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Witcover (2010), p. 59.

- ^ Harriman, Jane (December 31, 1969). "Joe Biden: Hope for Democratic Party in '72?". Newspapers.com. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Delaware Republican State Headquarters (1970). "Republican Information Center: 1970 List of Candidates" (PDF). University of Delaware Library Institutional Repository. Newark, DE: University of Delaware. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "County Ponders Housing Code". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. October 1, 1969. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lockman, Norm (December 20, 1969). "New Housing Code Favored for County". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "County Council to Take Oath". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. January 2, 1971. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Conner Calls Shake of 7 Lucky Omen for Council". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. January 6, 1971. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Maloney Seeks New Businesses". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. January 2, 1973. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Swift Seeks 4th District County Seat". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. March 30, 1972. p. 41. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Frump, Bob (November 8, 1972). "GOP Decade Ends with Slawik Win". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Zintl, Terry (March 14, 1973). "Shop Center Hackles Rise In Hockessin". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. p. 64. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Witcover (2010), p. 62.

- ^ "President Joe Biden: 25 Things You Don't Know About Me!". Us Weekly. A360 Media LLC. January 20, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "Biden's Wife, Child Killed in Car Crash". The New York Times. December 19, 1972. p. 9. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Witcover (2010), pp. 93, 98.

- ^ Levey, Noam M. (August 24, 2008). "In his home state, Biden is a regular Joe". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ Orr, Bob (March 24, 2009). "Driver In Biden Crash Wanted Name Cleared". CBS News. New York, NY.

- ^ Kipp, Rachel (September 4, 2008). "No DUI in crash that killed Biden's 1st wife, but he's implied otherwise". The News Journal. p. A.1. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "A Senator's Past: The Biden Car Crash". Inside Edition. August 27, 2008. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ^ Orr, Bob (March 24, 2009). "Driver In Biden Crash Wanted Name Cleared". CBS News. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Hamilton, Carl (October 30, 2008). "Daughter of man in '72 Biden crash seeks apology from widowed Senator". Newark Post. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Kruse, Michael (January 25, 2019). "How Grief Became Joe Biden's 'Superpower'". Politico. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Biden, Promises to Keep, p. 81

- ^ Bumiller, Elisabeth (December 14, 2007). "Biden Campaigning With Ease After Hardships". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ "On Becoming Joe Biden". Morning Edition. NPR. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on September 9, 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. (August 24, 2008). "Jill Biden Heads Toward Life in the Spotlight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Dart, Bob (October 24, 2008). "Bidens met, forged life together after tragedy". Orlando Sentinel. Cox News Service. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Biden, Promises to Keep, p. 117.

- ^ Sarkadi, Zsolt (November 8, 2020). "Biden és felesége 1977-ben a Balatonnál voltak nászúton". 444.hu (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ Adler, Katya (November 8, 2020). "US election: What does Joe Biden's win mean for Brexit Britain and Europe?". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ Biden, Promises to Keep, p. 113.

- ^ Gibson, Ginger (August 25, 2008). "Parishioners not surprised to see Biden at usual Mass". The News Journal. p. A.12. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "Ashley Biden and Howard Krein". The New York Times. June 3, 2012. p. ST15. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Cooper, Christopher (August 20, 2008). "Biden's Foreign Policy Background Carries Growing Cachet". The Wall Street Journal. p. A4. Archived from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ Helsel, Phil (May 31, 2015). "Beau Biden, Son of Vice President Joe Biden, Dies After Battle With Brain Cancer". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Kane, Paul (May 31, 2015). "Family losses frame Vice President Biden's career". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "How President Biden's Son, Beau Biden, Died of Brain Cancer". Advanced Neurosurgery Associates. December 18, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Evans, Heidi (December 28, 2008). "From a blind date to second lady, Jill Biden's coming into her own". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ Altman, Lawrence K. (February 23, 1998). "The Doctor's World; Subtle Clues Are Often The Only Warnings Of Perilous Aneurysms". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ a b c Altman, Lawrence K. (October 19, 2008). "Many Holes in Disclosure of Nominees' Health". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ "Biden Resting After Surgery For Second Brain Aneurysm". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 4, 1988. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Woodward, Calvin (August 23, 2008). "V.P. candidate profile: Sen. Joe Biden". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ Evon, Dan (October 16, 2020). "Did Biden Teach Constitutional Law for 21 Years?". Snopes. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Fauzia, Miriam (October 28, 2020). "Fact check: If he loses election, Biden said he wants to teach, but where is uncertain". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "Faculty: Joseph R. Biden, Jr". Widener University School of Law. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ^ "Senator Biden becomes Vice President-elect". Widener University School of Law. November 6, 2008. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ Purchla, Matt (August 26, 2008). "For Widener Law students, a teacher aims high". Metro Philadelphia. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ^ Carey, Kathleen E. (August 27, 2008). "Widener students proud of Biden". Delaware County Daily and Sunday Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ^ Bruggeman, Lucien (September 14, 2023). "What to know about the Hunter Biden investigations". ABC News. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Levenson, Michael (December 8, 2023). "A Timeline of Hunter Biden's Life and Legal Troubles". The New York Times. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "Joe Biden Met Nearly Every Foreign Associate Funneling His Family Millions". United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability. February 14, 2024. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Nelson, Steven (December 6, 2023). "Biden denies 'lies' he talked with son, brother's business partners". New York Post. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "200 Faces for the Future". Time. July 15, 1974. Archived from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ Kelley, Kitty (June 1, 1974). "Death and the All-American Boy". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c Almanac of American Politics 2008, p. 366.

- ^ "Obama introduces Biden as running mate". CNN. August 23, 2008. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ^ Users, Social Media (October 10, 2020). "Biden did not eulogize former KKK "grand wizard"". AP News. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Youngman, Sam (June 28, 2010). "Biden remembers Byrd as mentor and 'dear friend'". The Hill. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Longest Serving Senators". United States Senate. United States Senate. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Dionne, E. J. Jr. (June 10, 1987). "Biden Joins Campaign for the Presidency". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Toner, Robin (August 31, 1987). "Biden, Once the Field's Hot Democrat, Is Being Overtaken by Cooler Rivals". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Taylor (1990), p. 83.

- ^ Taylor (1990), pp. 108–109.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (September 12, 1987). "Biden's Debate Finale: An Echo From Abroad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Randolph, Eleanor (September 13, 1987). "Plagiarism Suggestion Angers Biden's Aides". The Washington Post. p. A6. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Risen, James; Shogan, Robert (September 16, 1987). "Differing Versions Cited on Source of Passages: Biden Facing New Flap Over Speeches". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Germond, Jack; Witcover, Jules (1989). Whose Broad Stripes and Bright Stars? The Trivial Pursuit of the Presidency 1988. Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-51424-8.

- ^ Smith, David (September 7, 2020). "Neil Kinnock on Biden's plagiarism 'scandal' and why he deserves to win: 'Joe's an honest guy'". The Guardian. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (September 16, 1987). "Biden Is Facing Growing Debate On His Speeches". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Dionne, E. J. Jr. (September 22, 1987). "Biden Admits Errors and Criticizes Latest Report". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ "1988 Road to the White House with Sen. Biden". C-SPAN via YouTube. August 23, 2008. Archived from the original on November 14, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ^ Flegenheimer, Matt (June 3, 2019). "Biden's First Run for President Was a Calamity. Some Missteps Still Resonate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Pomper, Gerald M. (1989). "The Presidential Nominations". The Election of 1988. Chatham House Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-934540-77-3. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Dionne, E. J. Jr. (September 24, 1987). "Biden Withdraws Bid for President in Wake of Furor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 21, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ "Sen. Biden not running for president". CNN. August 12, 2003. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ^ Balz, Dan (February 1, 2007). "Biden Stumbles at the Starting Gate". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ "Transcript: The Democratic Debate". ABC News. August 19, 2007. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ^ Farrell, Joelle (November 1, 2007). "A noun, a verb and 9/11". Concord Monitor. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ^ "Iowa Democratic Party Caucus Results". Iowa Democratic Party. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ Murray, Shailagh (January 4, 2008). "Biden, Dodd Withdraw From Race". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 20, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- ^ "Conventions 2008: Sen. Joseph Biden (D)". National Journal. August 25, 2008. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Heilemann, John; Halperin, Mark (2010). Game Change: Obama and the Clintons, McCain and Palin, and the Race of a Lifetime. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-173363-5.

- ^ a b Traub, James (November 24, 2009). "After Cheney". The New York Times Magazine. p. MM34. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Wolffe, Renegade, p. 218.

- ^ a b c Leibovich, Mark (September 19, 2008). "Meanwhile, the Other No. 2 Keeps On Punching". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (September 14, 2008). "Joe Who?". ABC News. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ Broder, John M. (October 30, 2008). "Hitting the Backroads, and Having Less to Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 31, 2008. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ Tumulty, Karen (October 29, 2008). "Hidin' Biden: Reining In a Voluble No. 2". Time. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ Leibovich, Mark (May 7, 2012). "For a Blunt Biden, an Uneasy Supporting Role". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ "Biden reliable running mate despite gaffes". Asbury Park Press. Associated Press. October 26, 2008.

- ^ "Obama: 'This is your victory'". CNN. November 4, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ^ Franke-Ruta, Garance (November 19, 2008). "McCain Takes Missouri". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ "President—Election Center 2008". CNN. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ Chase, Randall (August 24, 2008). "Biden Wages 2 Campaigns At Once". Fox News. Associated Press. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- ^ Nuckols, Ben (November 4, 2008). "Biden wins 7th Senate term but may not serve". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ Gaudiano, Nicole (January 7, 2009). "A bittersweet oath for Biden". The News Journal. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ Turner, Trish (January 15, 2009). "Senate Releases $350 Billion in Bailout Funds to Obama". Fox News. Associated Press. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Milford, Phil (November 24, 2008). "Kaufman Picked by Governor to Fill Biden Senate Seat (Update 3)". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on November 16, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ Kraushaar, Josh (November 24, 2008). "Ted Kaufman to succeed Biden in Senate". Politico. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ Hulse, Carl (January 25, 2010). "Biden's Son Will Not Run for Delaware's Open Senate Seat". The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Plemons, Carly (February 29, 2024). "eHealth". Why is Health Insurance so Expensive?. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ Thrush, Glenn (February 8, 2024). "Special Counsel Report Clears Biden on Documents but Raises Questions on His Memory". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ Bycoffe, Aaron (February 7, 2017). "Pence Has Already Done Something Biden Never Did: Break A Senate Tie". FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

Twelve vice presidents, including Biden, never broke a tie; Biden was the longest-serving vice president to never do so.

- ^ "Joe Biden still undecided on presidential run". BBC News. September 11, 2015. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Mason, Jeff (October 21, 2015). "Biden says he will not seek 2016 Democratic nomination". aol.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ Reilly, Mollie (October 21, 2015). "Joe Biden Is Not Running For President In 2016". Huff Post. Archived from the original on April 5, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ McCain Nelson, Colleen; Nicholas, Peter (October 21, 2015). "Joe Biden Decides Not to Enter Presidential Race". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ Fabian, Jordan (January 6, 2016). "Biden regrets not running for president 'every day'". The Hill. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ Dovere, Edward-Isaac (June 9, 2016). "Joe Biden endorses Hillary Clinton". Politico. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Shabad, Rebecca (June 20, 2016). "Joe Biden slams Donald Trump on wall, Muslim entry ban". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Parks, Maryalice (October 22, 2016). "Biden Says He Wishes He Could Take Trump 'Behind the Gym' Over Groping Comments". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Hingston, Sandy (October 23, 2021). "The Biden Administration Keeps Tapping Penn People for Major Roles: D.C.'s gain is Philly's loss". Philadelphia. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ O'Brien, Sara Ashley (March 12, 2017). "Joe Biden: The fight against cancer is bipartisan". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on May 26, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Kane, Paul (June 11, 2018). "Biden wraps up book tour amid persistent questions about the next chapter". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Viser, Matt; Narayanswamy, Anu (July 9, 2019). "Joe Biden earned $15.6 million in the two years after leaving the vice presidency". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Friedman, Megan (August 30, 2018). "Joe Biden Just Gave an Incredibly Powerful Speech at John McCain's Memorial". Town & Country. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Ockerman, Emma (October 25, 2018). "Two new pipe bombs said to target Joe Biden". Vice News. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Hays, Tom; Neumeister, Larry (August 5, 2019). "Cesar Sayoc, the Florida man who sent pipe bombs to Trump critics, is sentenced to 20 years". AP News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2022.

- ^ Hutchins, Ryan (May 28, 2017). "Biden backs Phil Murphy, says N.J. governor's race 'most important' in nation". Politico. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Dovere, Edward-Isaac (March 26, 2014). "VP's LGBT comments raise eyebrows". Politico. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Ananthalakshmi, A. (March 30, 2019). "Brunei defends tough new Islamic laws against growing backlash". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Eder, Steve; Glueck, Katie (July 9, 2019). "Joe Biden's Tax Returns Show More Than $15 Million in Income After 2016". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Charnetzki, Tori (January 10, 2018). "New Quad City Super PAC: "Time for Biden"". WVIK. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ Scherer, Michael; Wagner, John (April 25, 2019). "Former vice president Joe Biden jumps into White House race". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ Dovere, Edward-Isaac (February 4, 2019). "Biden's Anguished Search for a Path to Victory". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ Arnold, Amanda; Lampen, Claire (April 12, 2020). "All the Women Who Have Spoken Out Against Joe Biden". The Cut. Archived from the original on December 17, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Brice-Saddler, Michael (March 29, 2019). "Nevada Democrat accuses Joe Biden of touching and kissing her without consent at 2014 event". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability". United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability. March 6, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Mahdawi, Arwa (March 28, 2020). "Why has the media ignored sexual assault allegations against Biden?". the Guardian. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ "Here's why the media isn't reporting on the Hunter Biden emails". NBC News. October 30, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Tom (June 21, 2023). "How fair was media coverage of the Hunter Biden story?". Poynter. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Gerth, Jeff (January 30, 2023). "The press versus the president, part one". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Mitchell, Amy; Gottfried, Jeffrey; Stocking, Galen; Matsa, Katerina Eva; Grieco, Elizabeth (October 2, 2017). "Covering President Trump in a Polarized Media Environment". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. Retrieved March 20, 2024.

- ^ Olorunnipa, Toluse; Janes, Chelsea; Sonmez, Felicia; Itkowitz, Colby; Wagner, John (August 19, 2020). "Joe Biden officially becomes the Democratic Party's nominee on convention's second night". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Ura, Alexa (January 2, 2021). "Ted Cruz says he'll object to certification of Electoral College votes that will make Joe Biden's victory official". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ Ballhaus, Andrew Restuccia and Rebecca, Trump Clears Way for Biden Transition Process to Begin After Weeks of GSA Delay, retrieved April 10, 2024

- ^ Huguelet, Austin (January 5, 2021). "Past objections to Electoral College vote counts for president". Springfield News-Leader. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ "Transcript of Trump's Speech at Rally Before US Capitol Riot". U.S. News & World Report. January 13, 2021. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Kimble, Lindsay (January 6, 2021). "Joe Biden Calls on Donald Trump to 'Step Up' amid Chaos Led by 'Extremists' at Capitol". People. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ Weissert, Will; Superville, Darlene (January 7, 2021). "Biden urges restoring decency after 'assault' on democracy". Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ King, Ledyard; Groppe, Maureen; Wu, Nicholas; Jansen, Bart; Subramanian, Courtney; Garrison, Joey (January 6, 2021). "Pence confirms Biden as winner, officially ending electoral count after day of violence at Capitol". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Biden's first act: Orders on pandemic, climate, immigration". Associated Press. January 20, 2021. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Erikson, Bo (January 20, 2021). "Biden signs executive actions on COVID, climate change, immigration and more". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ "Joe Biden is taking executive action at a record pace". The Economist. January 22, 2021. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Cassella, Megan (January 22, 2021). "Biden signs executive orders aimed at combating hunger, protecting workers". Politico. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Allassan, Fadel; Perano, Ursula (January 20, 2021). "Biden will issue executive order to rescind Keystone XL pipeline permit". Axios. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Massie, Graeme (January 23, 2021). "Canada's Trudeau 'disappointed' with Biden order to cancel Keystone pipeline". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 9, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Nickel, Rod; Volcovici, Valerie (January 21, 2021). "TC Energy cuts jobs as Keystone pipeline nixed, but markets start to move on". Reuters. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Keith, Tamara (February 3, 2021). "With 28 Executive Orders Signed, President Biden Is Off To A Record Start". NPR. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Megerian, Chris; Miller, Zeke (March 11, 2022). "Biden relief plan: Major victory gets mixed one-year reviews". AP News. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Gallup, Inc.; Jones, Jeffrey M. (January 18, 2022). -polarized.aspx "Biden Year One Approval Ratings Subpar, Extremely Polarized". Gallup.com. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Frostenson, Sarah (October 12, 2021). "Why Has Biden's Approval Rating Gotten So Low So Quickly?". FiveThirtyEight. Archived from the original on October 12, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ Graham, David A. (November 19, 2021). "Six Theories of Joe Biden's Crumbling Popularity". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Rupar, Aaron (September 20, 2021). "Why Biden's approval numbers have sagged, explained by an expert". Vox. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ Montanaro, Domenico (September 2, 2021). "Biden's Approval Rating Hits A New Low After The Afghanistan Withdrawal". NPR. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ Liptak, Kevin; Mattingly, Phil (January 28, 2022). "Biden is aiming to hit the road to reset his presidency. He starts with yet another stop in Pennsylvania". CNN. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ "President Biden Job Approval". RealClearPolitics. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ Daniel, Will (July 18, 2022). "Inflation drives President Biden's economic approval rating to a record low". Fortune. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ Subramanian, Courtney (January 11, 2022). "'Let the majority prevail': Biden backs filibuster change to pass voting rights in Atlanta speech". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Foran, Clare; Zaslav, Ali; Barrett, Ted (January 19, 2022). "Senate Democrats suffer defeat on voting rights after vote to change rules fails". CNN. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Wingrove, Josh; Sink, Justin (July 21, 2022). "Biden Tests Positive for Covid, Has Mild Symptoms, White House Says". Bloomberg News. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Shear, Michael (July 21, 2022). "Biden, 79, is experiencing fatigue, a runny nose and a dry cough after testing positive". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Liptak, Kevin; Klein, Betsy; Sullivan, Kate (July 27, 2022). "Biden 'feeling great' and back to work in person after testing negative for Covid-19". CNN. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ CNN, Kevin Liptak (July 30, 2022). "President Joe Biden tests positive for Covid-19 again". CNN. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ O'Keefe, Ed; Cook, Sara (September 2, 2022). "Biden delivers prime-time speech on the "battle for the soul of the nation" in Philadelphia". CBS News. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan (September 2, 2022). "Four takeaways from President Biden's speech in Philadelphia". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ Naughtie, Andrew (September 5, 2022). "Jan 6 committee members back Biden remarks on Trump 'fascism' after rally guest defends neo-Nazi rioter: Joe Biden's warnings of creeping fascism on the pro-Trump right have fired up ex-president's followers and dissenters alike". The Independent. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ Gallup, Inc.; Jones, Jeffrey M. (April 3, 2024). "Biden Bests Trump on Likability; Trump Seen as Better Leader". Gallup.com. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Gracia, Shanay; Hartig, Hannah (March 19, 2024). "About 1 in 4 Americans have unfavorable views of both Biden and Trump". Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 9, 2024.