Digital divide

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2021) |

The digital divide is the unequal access to digital technology, including smartphones, tablets, laptops, and the internet.[1] The digital divide creates a division and inequality around access to information and resources.[1] In the Information Age in which information and communication technologies (ICTs) have eclipsed manufacturing technologies as the basis for world economies and social connectivity, people without access to the Internet and other ICTs are at a socio-economic disadvantage, for they are unable or less able to find and apply for jobs, shop and sell online, participate democratically, or research and learn.[2]

Historical background

The historical roots of the digital divide in Europe reach back to the increasing gap that occurred during the early modern period between those who could and couldn't access the real time forms of calculation, decision-making and visualization offered via written and printed media.[3] Within this context, ethical discussions regarding the relationship between education and the free distribution of information were raised by thinkers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Immanuel Kant and Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778). The latter advocated that governments should intervene to ensure that any society's economic benefits should be fairly and meaningfully distributed. Amid the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, Rousseau's idea helped to justify poor laws that created a safety net for those who were harmed by new forms of production. Later when telegraph and postal systems evolved, many used Rousseau's ideas to argue for full access to those services, even if it meant subsidizing hard to serve citizens. Thus, "universal services"[4] referred to innovations in regulation and taxation that would allow phone services such as AT&T in the United States serve hard to serve rural users. In 1996, as telecommunications companies merged with Internet companies, the Federal Communications Commission adopted Telecommunications Services Act of 1996 to consider regulatory strategies and taxation policies to close the digital divide. Though the term "digital divide" was coined among consumer groups that sought to tax and regulate Information and communications technology (ICeT) companies to close the digital divide, the topic soon moved onto a global stage. The focus was the World Trade Organization which passed a Telecommunications Services Act, which resisted regulation of ICT companies, so that they would be required to serve hard to serve individuals and communities. In 1999, in an effort to assuage anti-globalization forces, the WTO hosted the "Financial Solutions to Digital Divide" in Seattle, USA, co-organized by Craig Warren Smith of Digital Divide Institute and Bill Gates Sr. the chairman of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. It was the catalyst for a full scale global movement to close the digital divide, which quickly spread to all sectors of the global economy.[5] In 2000, US president Bill Clinton mentioned the term in the State of the Union Address.

During the COVID-19 Pandemic

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments worldwide issued stay-at-home orders that established lockdowns, quarantines, restrictions, and closures. The resulting interruptions in schooling, public services, and business operations drove nearly half of the world's population into seeking alternative methods to conduct their lives while in isolation.[6] These methods included telemedicine, virtual classrooms, online shopping, technology-based social interactions and working remotely, all of which require access to high-speed or broadband internet access and digital technologies. A Pew Research Center study reports that 90% of Americans describe the use of the internet as "essential" during the pandemic.[7]

According to the Pew Research Center, 59% of children from lower income families were likely to face digital obstacles in completing assignments.[7] These obstacles included the use of a cellphone to complete homework, having to use public WiFi because of unreliable service in the home, and lack of access to a computer in the home. This difficulty, titled the homework gap, affects more than 30% of K-12 students living below the poverty threshold, and disproportionally affects American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, and Hispanic students.[8][9]

A lack of "tech readiness", that is, confident and independent use of devices, was reported among the elderly; with more than 50% reporting an inadequate knowledge of devices and more than one-third reporting a lack of confidence.[7][10] This aspect of the digital divide and the elderly occurred during the pandemic as healthcare providers increasingly relied upon telemedicine to manage chronic and acute health conditions.[11]

Aspects

There are manifold definitions of the digital divide, all with slightly different emphasis, which is evidenced by related concepts like digital inclusion,[12] digital participation,[13] digital skills,[14] media literacy,[15] and digital accessibility.[16]

Infrastructure

The infrastructure by which individuals, households, businesses, and communities connect to the Internet address the physical mediums that people use to connect to the Internet such as desktop computers, laptops, basic mobile phones or smartphones, iPods or other MP3 players, gaming consoles such as Xbox or PlayStation, electronic book readers, and tablets such as iPads.[17]

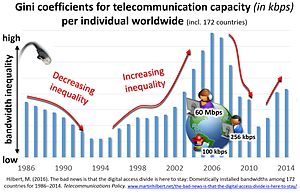

Traditionally, the nature of the divide has been measured in terms of the existing numbers of subscriptions and digital devices. Given the increasing number of such devices, some have concluded that the digital divide among individuals has increasingly been closing as the result of a natural and almost automatic process.[19][20] Others point to persistent lower levels of connectivity among women, racial and ethnic minorities, people with lower incomes, rural residents, and less educated people as evidence that addressing inequalities in access to and use of the medium will require much more than the passing of time.[21][22] Recent studies have measured the digital divide not in terms of technological devices, but in terms of the existing bandwidth per individual (in kbit/s per capita).[23][18]

As shown in the Figure on the side, the digital divide in kbit/s is not monotonically decreasing but re-opens up with each new innovation. For example, "the massive diffusion of narrow-band Internet and mobile phones during the late 1990s" increased digital inequality, as well as "the initial introduction of broadband DSL and cable modems during 2003–2004 increased levels of inequality".[23] During the mid-2000s, communication capacity was more unequally distributed than during the late 1980s, when only fixed-line phones existed. The most recent increase in digital equality stems from the massive diffusion of the latest digital innovations (i.e. fixed and mobile broadband infrastructures, e.g. 5G and fiber optics FTTH).[24][failed verification] Measurement methodologies of the digital divide, and more specifically an Integrated Iterative Approach General Framework (Integrated Contextual Iterative Approach – ICI) and the digital divide modeling theory under measurement model DDG (Digital Divide Gap) are used to analyze the gap existing between developed and developing countries, and the gap among the 27 members-states of the European Union.[25][26]

Skills and digital literacy

Research from 2001 showed that the digital divide is more than just an access issue and cannot be alleviated merely by providing the necessary equipment. There are at least three factors at play: information accessibility, information utilization, and information receptiveness. More than just accessibility, the digital divide consists on society's lack of knowledge on how to make use of the information and communication tools once they exist within a community.[27] Information professionals have the ability to help bridge the gap by providing reference and information services to help individuals learn and utilize the technologies to which they do have access, regardless of the economic status of the individual seeking help.[28]

Location

Internet connectivity can be utilized at a variety of locations such as homes, offices, schools, libraries, public spaces, Internet cafes and others. There are also varying levels of connectivity in rural, suburban, and urban areas. [29][30]

In 2017, the Wireless Broadband Alliance published the white paper The Urban Unconnected, which highlighted that in the eight countries with the world's highest GNP about 1.75 billion people lived without an Internet connection and one third of them resided in the major urban centers. Delhi (5.3 millions, 9% of the total population), São Paulo (4.3 millions, 36%), New York (1.6 mln, 19%), and Moscow (2.1 mln, 17%) registered the highest percentages of citizens that weren't provided of any type of Internet access.[31]

As of 2021, only about half of the world's population had access to the internet leaving 3.7 billion people without internet. A majority of those are from developing countries with a large portion of them being women.[32] One of the leading factors of this is that globally different governments have different policies relating to issues such as privacy, data governance, speech freedoms as well as many other factors. This makes it challenging for technology companies to create an environment for users that are from certain countries due to restrictions put in place in the region. This disproportionately impacts the different regions of the world with Europe having the highest percentage of the population online while Africa has the lowest. From 2010 to 2014 Europe went from 67% to 75% and in the same time span Africa went from 10% to 19%.[33]

Network speeds play a large role in the quality and experience a user takes away from using the internet. Large cities and towns may have better access to high speed internet than rural areas which may have limited or no service.[34] Households can be locked into a specific service provider since it may be the only carrier that even offers service to the area. This applies to regions that have developed networks like the United States but also applies to developing countries, creating very large areas that have virtually no coverage.[35] In instances like this there are very limited options that a person could take to solve this since the issue is mainly infrastructure. Technologies that provide an internet connection through satellite are becoming more common, like Starlink, but are still not available for people in many regions. [36]

Based on location, a connection may have speeds that are virtually unusable solely because a network provider has limited infrastructure in the area which emphasizes how important location is. For example, to download 5GB of data in Taiwan it would take approximately 8 minutes while the same download would take 1 day, 6 hours, 1minute, and 40 seconds to download in Yemen.[37]

Applications

Common Sense Media, a nonprofit group based in San Francisco, surveyed almost 1,400 parents and reported in 2011 that 47 percent of families with incomes more than $75,000 had downloaded apps for their children, while only 14 percent of families earning less than $30,000 had done so.[38]

Reasons and correlating variables

As of 2014, the gap in a digital divide was known to exist for a number of reasons. Obtaining access to ICTs and using them actively has been linked to demographic and socio-economic characteristics including income, education, race, gender, geographic location (urban-rural), age, skills, awareness, political, cultural and psychological attitudes.[39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][excessive citations] Multiple regression analysis across countries has shown that income levels and educational attainment are identified as providing the most powerful explanatory variables for ICT access and usage.[47] Evidence was found that Caucasians are much more likely than non-Caucasians to own a computer as well as have access to the Internet in their homes. As for geographic location, people living in urban centers have more access and show more usage of computer services than those in rural areas. Gender was previously thought to provide an explanation for the digital divide, many thinking ICT were male gendered, but controlled statistical analysis has shown that income, education and employment act as confounding variables and that women with the same level of income, education and employment actually embrace ICT more than men (see Women and ICT4D).[48] However, each nation has its own set of causes or the digital divide. For example, the digital divide in Germany is unique because it is not largely due to difference in quality of infrastructure.[49]

The correlation between income and internet use suggests that the digital divide persists at least in part due to income disparities.[50] Most commonly, a digital divide stems from poverty and the economic barriers that limit resources and prevent people from obtaining or otherwise using newer technologies.

In research, while each explanation is examined, others must be controlled to eliminate interaction effects or mediating variables,[39] but these explanations are meant to stand as general trends, not direct causes. Measurements for the intensity of usages, such as incidence and frequency, vary by study. Some report usage as access to Internet and ICTs while others report usage as having previously connected to the Internet. Some studies focus on specific technologies, others on a combination (such as Infostate, proposed by Orbicom-UNESCO, the Digital Opportunity Index, or ITU's ICT Development Index).

Economic gap in the United States

During the mid-1990s, the United States Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications & Information Administration (NTIA) began publishing reports about the Internet and access to and usage of the resource. The first of three reports is titled "Falling Through the Net: A Survey of the "Have Nots" in Rural and Urban America" (1995),[51] the second is "Falling Through the Net II: New Data on the Digital Divide" (1998),[52] and the final report "Falling Through the Net: Defining the Digital Divide" (1999).[53] The NTIA's final report attempted clearly to define the term digital divide; "the digital divide—the divide between those with access to new technologies and those without—is now one of America's leading economic and civil rights issues. This report will help clarify which Americans are falling further behind so that we can take concrete steps to redress this gap."[53] Since the introduction of the NTIA reports, much of the early, relevant literature began to reference the NTIA's digital divide definition. The digital divide is commonly defined as being between the "haves" and "have-nots".[53][54]

The U.S. Federal Communication Commission's (FCC) 2019 Broadband Deployment Report indicated that 21.3 million Americans do not have access to wired or wireless broadband internet.[55] As of 2020, BroadbandNow, an independent research company studying access to internet technologies, estimated that the actual number of United States Americans without high-speed internet is twice that amount.[56] According to a 2021 Pew Research Center report, smartphone ownership and internet use has increased for all Americans, however, a significant gap still exists between those with lower incomes and those with higher incomes:[57] U.S. households earning $100K or more are twice as likely to own multiple devices and have home internet service as those making $30K or more, and three times as likely as those earning less than $30K per year.[57] The same research indicated that 13% of the lowest income households had no access to internet or digital devices at home compared to only 1% of the highest income households.[57]

According to a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults executed from January 25 to February 8, 2021, the digital lives of Americans with high and low incomes are varied. Conversely, the proportion of Americans that use home internet or cell phones has maintained constant between 2019 and 2021. A quarter of those with yearly average earnings under $30,000 (24%) says they don't own smartphones. Four out of every ten low-income people (43%) do not have home internet access or a computer (43%). Furthermore, the more significant part of lower-income Americans does not own a tablet device.[58]

On the other hand, every technology is practically universal among people earning $100,000 or higher per year. Americans with larger family incomes are also more likely to buy a variety of internet-connected products. Wifi at home, a smartphone, a computer, and a tablet are used by around six out of ten families making $100,000 or more per year, compared to 23 percent in the lesser household.[58]

Racial gap

Although many groups in society are affected by a lack of access to computers or the Internet, communities of color are specifically observed to be negatively affected by the digital divide.[59] Pew research shows that as of 2021, home broadband rates are 81% for White households, 71% for Black households and 65% for Hispanic households.[60] While 63% of Black adults find the lack of broadband to be a disadvantage, only 49% of White adults do.[59] Smartphone and tablet ownership remains consistent with about 8 out of 10 Black, White, and Hispanic individuals reporting owning a smartphone and half owning a tablet.[59] A 2021 survey found that a quarter of hispanics rely on their smartphone and do not have access to broadband.[59]

Physical and Mental Disability Gap

Inequities in access to information technologies are present among individuals living with a physical disability in comparison to those who are not living with a disability. According to The Pew Research Center, 54% of households with a person who has a disability have home Internet access compared to 81% of households that have home Internet access and do not have a person who has a disability.[61] The type of disability an individual has can prevent one from interacting with computer screens and smartphone screens, such as having a quadriplegia disability or having a disability in the hands. However, there is still a lack of access to technology and home Internet access among those who have a cognitive and auditory disability as well. There is a concern of whether or not the increase in the use of information technologies will increase equality through offering opportunities for individuals living with disabilities or whether it will only add to the present inequalities and lead to individuals living with disabilities being left behind in society.[62] Issues such as the perception of disabilities in society, Federal and state government policy, corporate policy, mainstream computing technologies, and real-time online communication have been found to contribute to the impact of the digital divide on individuals with disabilities. Other type of disabilities that are not always considered are severe mental illnesses such as psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia). Some of these patients who are also cognitively affected by their symptoms and medications, might suffer from function impairments resulting in less access to digital technologies [63]

People with disabilities are also the targets of online abuse. Online disability hate crimes have increased by 33% across the UK between 2016–17 and 2017–18 according to a report published by Leonard Cheshire, a health and welfare charity.[64] Accounts of online hate abuse towards people with disabilities were shared during an incident in 2019 when model Katie Price's son was the target of online abuse that was attributed to him having a disability. In response to the abuse, a campaign was launched by Price to ensure that Britain's MP's held those who are guilty of perpetuating online abuse towards those with disabilities accountable.[65] Online abuse towards individuals with disabilities is a factor that can discourage people from engaging online which could prevent people from learning information that could improve their lives. Many individuals living with disabilities face online abuse in the form of accusations of benefit fraud and "faking" their disability for financial gain, which in some cases leads to unnecessary investigations.

Gender gap

Due to the rapidly declining price of connectivity and hardware, skills deficits have eclipsed barriers of access as the primary contributor to the gender digital divide. Studies show that women are less likely to know how to leverage devices and Internet access to their full potential, even when they do use digital technologies.[66] In rural India, for example, a study found that the majority of women who owned mobile phones only knew how to answer calls. They could not dial numbers or read messages without assistance from their husbands, due to a lack of literacy and numeracy skills.[67] A survey of 3,000 respondents across 25 countries found that adolescent boys with mobile phones used them for a wider range of activities, such as playing games and accessing financial services online. Adolescent girls in the same study tended to use just the basic functionalities of their phone, such as making calls and using the calculator.[68] Similar trends can be seen even in areas where Internet access is near-universal. A survey of women in nine cities around the world revealed that although 97% of women were using social media, only 48% of them were expanding their networks, and only 21% of Internet-connected women had searched online for information related to health, legal rights or transport.[68] In some cities, less than one quarter of connected women had used the Internet to look for a job.[66]

Studies show that despite strong performance in computer and information literacy (CIL), girls do not have confidence in their ICT abilities. According to the International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS) assessment girls' self-efficacy scores (their perceived as opposed to their actual abilities) for advanced ICT tasks were lower than boys'.[69][66]

A paper published by J. Cooper from Princeton University points out that learning technology is designed to be receptive to men instead of women. Overall, the study presents the problem of various perspectives in society that are a result of gendered socialization patterns that believe that computers are a part of the male experience since computers have traditionally presented as a toy for boys when they are children.[70] This divide is followed as children grow older and young girls are not encouraged as much to pursue degrees in IT and computer science. In 1990, the percentage of women in computing jobs was 36%, however in 2016, this number had fallen to 25%. This can be seen in the under representation of women in IT hubs such as Silicon Valley.[71]

There has also been the presence of algorithmic bias that has been shown in machine learning algorithms that are implemented by major companies.[clarification needed] In 2015, Amazon had to abandon a recruiting algorithm that showed a difference between ratings that candidates received for software developer jobs as well as other technical jobs. As a result, it was revealed that Amazon's machine algorithm was biased against women and favored male resumes over female resumes. This was due to the fact that Amazon's computer models were trained to vet patterns in resumes over a 10-year period. During this ten-year period, the majority of the resumes belong to male individuals, which is a reflection of male dominance across the tech industry.[72]

Age gap

This article needs to be updated. (July 2020) |

Age matters!Older adults, those ages 60 and up, face various barriers that contribute to their lack of access to information and communication technologies (ICTs). Many adults are "digital immigrants" who have not had lifelong exposure to digital media and have had to adapt to incorporating it in their lives.[73] A 2012 study found that 53% of people aged 65 and over were Internet users, compared to 82% of people aged 18 and over.[74] This "grey divide" can be due to factors such as concern over security, motivation and self-efficacy, decline of memory or spatial orientation, cost, or lack of support.[75] The aforementioned variables of race, disability, gender, and sexual orientation also add to the barriers for older adults.

Many older adults may have physical or mental disabilities that render them homebound and financially insecure. They may be unable to afford Internet access or lack transportation to use computers in public spaces, the benefits of which would be enhancing their health and reducing their social isolation and depression. Homebound older adults would benefit from Internet use by using it to access health information, use telehealth resources, shop and bank online, and stay connected with friends or family using email or social networks.[76]

Those in the more privileged socio-economic positions and have a higher level of education are more likely to have Internet access than those older adults living in poverty. Lack of access to the Internet inhibits "capitalism-enhancing activities" such as accessing government assistance, job opportunities, or investments. The results of the U.S. Federal Communication Commission's 2009 National Consumer Broadband Service Capability Survey shows that older women are less likely to use the Internet, especially for capital enhancing activities, than their male counterparts.[77] For example, poor and disadvantaged children and teenagers spend more time using digital devices for entertainment and less time interacting with people face-to-face compared to children and teenagers in well-off families.[78]

The age gap differs between countries. As of 2016[update], in the United States, the number of people 65 and over who own smartphones had risen from 18% to 42% since 2013.[79] In Europe however, 51% of individuals over the age of 50 do not use the internet.[80] For countries like China which is projected to be an "aged society", a country that has 14% of the population over the age of 65, there is a spotlight on decreasing the age gap and creating more inclusivity for the elderly in the digital age.[81]

Global level

The divide between differing countries or regions of the world is referred to as the global digital divide,which examines the technological gap between developing and developed countries.[82] The divide within countries (such as the digital divide in the United States) may refer to inequalities between individuals, households, businesses, or geographic areas, usually at different socioeconomic levels or other demographic categories. In contrast, the global digital divide describes disparities in access to computing and information resources, and the opportunities derived from such access.[83] As the internet rapidly expands it is difficult for developing countries to keep up with the constant changes. In 2014 only three countries (China, US, Japan) host 50% of the globally installed bandwidth potential.[18] This concentration is not new, as historically only ten countries have hosted 70–75% of the global telecommunication capacity (see Figure). The U.S. lost its global leadership in terms of installed bandwidth in 2011, replaced by China, who hosted more than twice as much national bandwidth potential in 2014 (29% versus 13% of the global total).[18]

Implications

Social capital

Once an individual is connected, Internet connectivity and ICTs can enhance his or her future social and cultural capital. Social capital is acquired through repeated interactions with other individuals or groups of individuals. Connecting to the Internet creates another set of means by which to achieve repeated interactions. ICTs and Internet connectivity enable repeated interactions through access to social networks, chat rooms, and gaming sites. Once an individual has access to connectivity, obtains infrastructure by which to connect, and can understand and use the information that ICTs and connectivity provide, that individual is capable of becoming a "digital citizen".[39]

Economic disparity

In the United States, the research provided by Unguarded Availability Services notes a direct correlation between a company's access to technological advancements and its overall success in bolstering the economy.[84] The study, which includes over 2,000 IT executives and staff officers, indicates that 69 percent of employees feel they do not have access to sufficient technology to make their jobs easier, while 63 percent of them believe the lack of technological mechanisms hinders their ability to develop new work skills.[84] Additional analysis provides more evidence to show how the digital divide also affects the economy in places all over the world. A BEG report suggests that in countries like Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K., the digital connection among communities is made easier, allowing for their populations to obtain a much larger share of the economies via digital business.[85] In fact, in these places, populations hold shares approximately 2.5 percentage points higher.[85] During a meeting with the United Nations a Bangladesh representative expressed his concern that poor and undeveloped countries would be left behind due to a lack of funds to bridge the digital gap.[86]

Education

The digital divide impacts children's ability to learn and grow in low-income school districts. Without Internet access, students are unable to cultivate necessary technological skills to understand today's dynamic economy.[87] The need for the internet starts while children are in school – necessary for matters such as school portal access, homework submission, and assignment research.[88] The Federal Communication Commission's Broadband Task Force created a report showing that about 70% of teachers give students homework that demand access to broadband.[89] Approximately 65% of young scholars use the Internet at home to complete assignments as well as connect with teachers and other students via discussion boards and shared files.[89] A recent study indicates that approximately 50% of students say that they are unable to finish their homework due to an inability to either connect to the Internet or in some cases, find a computer.[89] This has led to a new revelation: 42% of students say they received a lower grade because of this disadvantage.[89] According to research conducted by the Center for American Progress, "if the United States were able to close the educational achievement gaps between native-born white children and black and Hispanic children, the U.S. economy would be 5.8 percent—or nearly $2.3 trillion—larger in 2050".[90]

In a reverse of this idea, well-off families, especially the tech-savvy parents in Silicon Valley, carefully limit their own children's screen time. The children of wealthy families attend play-based preschool programs that emphasize social interaction instead of time spent in front of computers or other digital devices, and they pay to send their children to schools that limit screen time.[78] American families that cannot afford high-quality childcare options are more likely to use tablet computers filled with apps for children as a cheap replacement for a babysitter, and their government-run schools encourage screen time during school. Students in school are also learning about the digital divide.[78]

Demographic differences

This section needs to be updated. (August 2019) |

Technology has developed significantly over time and has "become key channels for interpersonal communication and interaction for sustaining relationships."[91] In 2020, COVID-19 changed the world. It did not only change the way people around the world lived their lives, but it also changed the way the entire world used technology. During this time, many people throughout the world, started using new technologies in order to interact with one another. However, for some it was hard, "Already vulnerable groups [were] likely to be least prepared to manage shifts necessary during the pandemic and digital inequalities are one way that the crisis might disproportionately impact those groups."[91] These vulnerable groups include those that are not as familiar or used to using technology. The COVID-19 pandemic also brought out different things such as new research in a variety of aspects. A lot of this research was based on statics. The Pew Research Center informs the world about "issues, attitudes, and trends" by being a fact tank of information for many people throughout the world to go off of.[92] People throughout the world use information from The Pew Research Center to study many things, includingthat of differences in use of technology. Based off of studies from the Pew Research Center, "Instagram: About half of Hispanic (52%) and Black Americans (49%) say they use the platform, compared with smaller shares of White Americans (35%) who say the same."[93] This quote is referring to the fact that more people of Hispanic and Black races use the Instagram platform more than that of White Americans. In order to conduct this test, the Pew Research Center had to interview 1,502 adults that live in the United States of America. They performed this study in a two-week time frame that spanned from January 25, 2021, to February 8, 2021. In order to get ahold of the United States adult citizens that were being served, the Pew Research Center used cellphones as well as landline phones. During this study, The Pew Research Center found that, "YouTube and Facebook continue to dominate the online landscape, with 81% and 69%, respectively, reporting using these sites."[93] The last time The Pew Research Center conducted this survey was 2019. Since then, "YouTube and Reddit were the only two platforms measures that saw statistically significant growth [...]"[93] Since 2019 was the last time that the center conducted this survey, the rise in usage from those particular apps is likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Out of all 1,502 United States adults that were surveyed, "Adults under 30 stand out for their use of Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok."[93] You can also notice a significant change when the age of the person taking this survey differs. According to the same Pew Research Center study, "[...] while 65% of adults ages 18 to 29 say they use Snapchat, just 2% of those 65 and older report using the app – a difference of 63 percentage points."[93] However, these results do depend on what app the people are being asked about. When The Pew Research Center asked about YouTube, "95% of those 18 to 29 say they use the platform, along with 91% of those 30 to 49 and 83% of adults 50 to 64." However, with this app in particular, when we move to the age group of 65 and older, "this shar drops substantially – to 49% [...]"[93] Although, for YouTube, the usage takes a substantial drop once the 65+ age is reached, it is still significantly more used by this age group than apps that were previously talked about such as TikTok.

According to the 2012 Pew Report "Digital Differences," a mere 62% of households in the United States who make less than $30,000 a year use the Internet, while 90% of those making between $50,000 and $75,000 had access.[87] Studies also show that only 51% of Hispanics and 49% of African Americans have high-speed Internet at home. This is compared to the 66% of Caucasians that also have high-speed Internet in their households.[87] Overall, 10% of all Americans do not have access to high-speed Internet, an equivalent of almost 34 million people.[94] As of 2016, the global effects of limiting technological developments in poorer nations, rather than simply the effects in the United States have been highlighted: rapid digital expansion excludes those who find themselves in the lower class. 60% of the world's population, almost 4 billion people, had no access to the Internet.[95]

Pew Research Center conducted another digital divide study between Jan. 25- Feb. 8, 2021. The results of this study found that about 25% of adults in the United States who make less than $30,000 a year do not own a smartphone, 43% of these adults do not have broadband internet access from their home and 41% do not own a tablet, such as an iPad.[96] All of this was found to be a given in households where adults make $100,000+ a year, often showing these homes to have multiple devices allowing access to the internet.[96]

It is also noted in the study that due to the lack of devices available within the home that connect to the internet, those households that earn less than $30,000 who do own a smartphone use that device to accomplish tasks higher income homes would normally reserve using a laptop or desktop computer to complete, such as applying to jobs.[96] Additionally, the survey also showed that 15% of all smartphone owning participants use only this device to access the internet, regardless of income.[97]

Facebook divide

The Facebook divide,[98][99][100][101] a concept derived from the "digital divide", is the phenomenon with regard to access to, use of, and impact of Facebook on society. It was coined at the International Conference on Management Practices for the New Economy (ICMAPRANE-17) on February 10–11, 2017.[102]

Additional concepts of Facebook Native and Facebook Immigrants were suggested at the conference. Facebook divide, Facebook native, Facebook immigrants, and Facebook left-behind are concepts for social and business management research. Facebook immigrants utilize Facebook for their accumulation of both bonding and bridging social capital. Facebook natives, Facebook immigrants, and Facebook left-behind induced the situation of Facebook inequality. In February 2018, the Facebook Divide Index was introduced at the ICMAPRANE conference in Noida, India, to illustrate the Facebook divide phenomenon.[103]

Solutions

As of 2009, the borderline between ICT as a necessity good and ICT as a luxury good was roughly around US$10 per person per month, or US$120 per year,[47] which means that people consider ICT expenditure of US$120 per year as a basic necessity. Since more than 40% of the world population lives on less than US$2 per day, and around 20% live on less than US$1 per day (or less than US$365 per year), these income segments would have to spend one third of their income on ICT (120/365 = 33%). The global average of ICT spending is at a mere 3% of income.[47] Potential solutions include driving down the costs of ICT, which includes low-cost technologies and shared access through Telecentres.[citation needed]

In 2022, the US Federal Communications Commission started a proceeding "to prevent and eliminate digital discrimination and ensure that all people of the United States benefit from equal access to broadband internet access service, consistent with Congress's direction in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.[104]

Since May 17, 2006, the United Nations has raised awareness of the divide by way of the World Information Society Day.[105] In 2001, it set up the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Task Force.[106] Later UN initiatives in this area are the World Summit on the Information Society since 2003, and the Internet Governance Forum, set up in 2006.

In the year 2000, the United Nations Volunteers (UNV) program launched its Online Volunteering service,[107] which uses ICT as a vehicle for and in support of volunteering. It constitutes an example of a volunteering initiative that effectively contributes to bridge the digital divide. ICT-enabled volunteering has a clear added value for development. If more people collaborate online with more development institutions and initiatives, this will imply an increase in person-hours dedicated to development cooperation at essentially no additional cost. This is the most visible effect of online volunteering for human development.[108]

Social media websites serve as both manifestations of and means by which to combat the digital divide. The former describes phenomena such as the divided users' demographics that make up sites such as Facebook, WordPress and Instagram. Each of these sites hosts communities that engage with otherwise marginalized populations.

Libraries

In 2010 an "online indigenous digital library as part of public library services" was created in Durban, South Africa to narrow the digital divide by not only giving the people of the Durban area access to this digital resource, but also by incorporating the community members into the process of creating it.[109]

In 2002, the Gates Foundation started the Gates Library Initiative which provides training assistance and guidance in libraries.[110]

In Kenya, lack of funding, language, and technology illiteracy contributed to an overall lack of computer skills and educational advancement. This slowly began to change when foreign investment began.[111][112] In the early 2000s, the Carnegie Foundation funded a revitalization project through the Kenya National Library Service. Those resources enabled public libraries to provide information and communication technologies to their patrons. In 2012, public libraries in the Busia and Kiberia communities introduced technology resources to supplement curriculum for primary schools. By 2013, the program expanded into ten schools.[113]

Effective use

Even though individuals might be capable of accessing the Internet, many are opposed by barriers to entry, such as a lack of means to infrastructure or the inability to comprehend or limit the information that the Internet provides. Some individuals can connect, but they do not have the knowledge to use what information ICTs and Internet technologies provide them. This leads to a focus on capabilities and skills, as well as awareness to move from mere access to effective usage of ICT.[114]

Community informatics (CI) focuses on issues of "use" rather than "access". CI is concerned with ensuring the opportunity not only for ICT access at the community level but also, according to Michael Gurstein, that the means for the "effective use" of ICTs for community betterment and empowerment are available.[115] Gurstein has also extended the discussion of the digital divide to include issues around access to and the use of "open data" and coined the term "data divide" to refer to this issue area.[116]

Criticism

Knowledge divide

Since gender, age, race, income, and educational digital divides have lessened compared to the past, some researchers suggest that the digital divide is shifting from a gap in access and connectivity to ICTs to a knowledge divide.[117] A knowledge divide concerning technology presents the possibility that the gap has moved beyond the access and having the resources to connect to ICTs to interpreting and understanding information presented once connected.[118]

Second-level digital divide

The second-level digital divide, also referred to as the production gap, describes the gap that separates the consumers of content on the Internet from the producers of content.[119] As the technological digital divide is decreasing between those with access to the Internet and those without, the meaning of the term digital divide is evolving.[117] Previously, digital divide research was focused on accessibility to the Internet and Internet consumption. However, with an increasing amount of the population gaining access to the Internet, researchers are examining how people use the Internet to create content and what impact socioeconomics are having on user behavior.[120] New applications have made it possible for anyone with a computer and an Internet connection to be a creator of content, yet the majority of user-generated content available widely on the Internet, like public blogs, is created by a small portion of the Internet-using population. Web 2.0 technologies like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Blogs enable users to participate online and create content without having to understand how the technology actually works, leading to an ever-increasing digital divide between those who have the skills and understanding to interact more fully with the technology and those who are passive consumers of it.[119]

Some of the reasons for this production gap include material factors like the type of Internet connection one has and the frequency of access to the Internet. The more frequently a person has access to the Internet and the faster the connection, the more opportunities they have to gain the technology skills and the more time they have to be creative.[121]

Other reasons include cultural factors often associated with class and socioeconomic status. Users of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to participate in content creation due to disadvantages in education and lack of the necessary free time for the work involved in blog or web site creation and maintenance.[121] Additionally, there is evidence to support the existence of the second-level digital divide at the K-12 level based on how educators' use technology for instruction.[122] Schools' economic factors have been found to explain variation in how teachers use technology to promote higher-order thinking skills.[122]

See also

| Library resources about Digital divide |

- Achievement gap

- Civic opportunity gap

- Computer technology for developing areas

- Digital divide by country

- Digital divide in Canada

- Digital divide in China

- Digital divide in South Africa

- Digital divide in Thailand

- Digital rights in the Caribbean

- Digital inclusion

- Digital rights

- Global Internet usage

- Government by algorithm

- Information society

- International communication

- Internet geography

- Internet governance

- List of countries by Internet connection speeds

- Light-weight Linux distribution

- Literacy

- National broadband plans from around the world

- NetDay

- Net neutrality

- Rural Internet

Groups devoted to digital divide issues

- Center for Digital Inclusion

- Digital Textbook a South Korean Project that intends to distribute tablet notebooks to elementary school students.

- Inveneo

- TechChange

- United Nations Information and Communication Technologies Task Force

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education, UNESCO, EQUALS Skills Coalition, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education, UNESCO, EQUALS Skills Coalition, UNESCO. UNESCO.

Citations

Vogels, E. A. (2021, September 10). Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption. Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption.

ProQuest | Databases, EBooks and Technology for Research. (n.d.). Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://about.proquest.com.

The British Museum. "Our Earliest Technology?" Smarthistory. Accessed October 12, 2022. Our earliest technology? – Smarthistory.

Apple. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.apple.com.

What Is The Digital Divide and How Is It Being Bridged?

Bureau, US Census. Census.gov, October 6, 2022. [2].

Wise, Jason. "How Many People Own Televisions in 2022? (Ownership Stats)." EarthWeb, September 6, 2022. How Many People Own Televisions in 2022? (Ownership Stats) - EarthWeb.

Published by Statista Research Department, and Sep 20. "Internet and Social Media Users in the World 2022." Statista, September 20, 2022. Internet and social media users in the world 2022.

References

- ^ a b Muschert, & Ragnedda, M. (2013). The digital divide : the internet and social inequality in international perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203069769

- ^ Park, Sora (2017). Digital capital. London: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-137-59332-0. OCLC 1012343673.

- ^ Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2022). Media and the Mind: Art, Science and Notebooks as Paper Machines, 1700-1830. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Jackson, Dr. Kim (September 26, 2000). "The Telecommunications Universal Service Obligation (USO)". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Craig Warren (2002). Digital Corporate Citizenship: The Business Response to the Digital Divide. Indianapolis: The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University. ISBN 1884354203.

- ^ Sandford, Alasdair (April 2, 2020). "Coronavirus: Half of humanity on lockdown in 90 countries". euronews. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ a b c McClain, Colleen; Vogels, Emily A.; Perrin, rew; Sechopoulos, Stella; Rainie, Lee (September 1, 2021). "The Internet and the Pandemic". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "The numbers behind the broadband "homework gap"". Pew Research Center. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Student Access to Digital Learning Resources Outside of the Classroom". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ Kakulla, Brittne (2021). "Older Adults Are Upgrading Tech for a Better Online Experience". AARP. doi:10.26419/res.00420.001. S2CID 234803399. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Health Literacy Online | health.gov". health.gov. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Dashboard – Digital inclusion". GOV.UK. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Homepage". Digital Participation Charter. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ "Tech Partnership Legacy". Thetechpartnership.com. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Media literacy". Ofcom. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ Rouse, Margaret. "What is digital accessibility? - Definition from WhatIs.com". Whatis.techtarget.com. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ Zickuher, Kathryn. 2011. Generations and their gadgets. Pew Internet & American Life Project.

- ^ a b c d Hilbert, Martin (2016). "The bad news is that the digital access divide is here to stay: Domestically installed bandwidths among 172 countries for 1986–2014". Telecommunications Policy. 40 (6): 567–581. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2016.01.006.

- ^ Compaine, B.M. (2001). The digital divide: Facing a crisis or creating a myth? Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

- ^ Dutton, W.H.; Gillett, S.E.; McKnight, L.W.; Peltu, M. (2004). "Bridging Broadband Internet Divides". Journal of Information Technology. 19 (1): 28–38. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jit.2000007. S2CID 11827716.

- ^ Eszter Hargittai. The Digital Divide and What to Do About It. New Economy Handbook, p. 824, 2003.

- ^ Kathryn zickuhr. Who's not online and why? Pew Research Center, 2013.

- ^ a b Hilbert, Martin (2013). "Technological information inequality as an incessantly moving target: The redistribution of information and communication capacities between 1986 and 2010" (PDF). Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technological. 65 (4): 821–835. doi:10.1002/asi.23020. S2CID 15820273.

- ^ SciDevNet (2014) How mobile phones increased the digital divide; http://www.scidev.net/global/data/scidev-net-at-large/how-mobile-phones-increased-the-digital-divide.html

- ^ Abdalhakim, Hawaf., (2009). An innovated objective digital divide measure, Journal of Communication and Computer, Volume 6, No.12 (Serial No.61), USA.

- ^ Paschalidou, Georgia, (2011), Digital divide and disparities in the use of new technologies, https://dspace.lib.uom.gr/bitstream/2159/14899/6/PaschalidouGeorgiaMsc2011.pdf

- ^ Mun-cho, K. & Jong-Kil, K. (2001). Digital divide: conceptual discussions and prospect, In W. Kim, T. Wang Ling, Y.j. Lee & S.S. Park (Eds.), The human society and the Internet: Internet-related socio-economic Issues, First International Conference, Seoul, Korea: Proceedings, Springer, New York, NY.

- ^ Aqili, S.; Moghaddam, A. (2008). "Bridging the digital divide: The role of librarians and information professionals in the third millennium". Electronic Library. 26 (2): 226–237. doi:10.1108/02640470810864118.

- ^ Livingston, Gretchen. 2010. Latinos and Digital Technology, 2010. Pew Hispanic Center

- ^ Ramalingam A, Kar SS (2014). "Is there a digital divide among school students? an exploratory study from Puducherry". J Educ Health Promot. 3: 30. doi:10.4103/2277-9531.131894 (inactive July 31, 2022). PMC 4089106. PMID 25013823.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - ^ "Digital Inclusion – Key to Prosperous & Smart Cities". Wireless Broadband Alliance. 2017.

- ^ "With Almost Half of World's Population Still Offline, Digital Divide Risks Becoming "New Face of Inequality", Deputy Secretary-General Warns General Assembly. Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". www.un.org. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "The Global Digital Divide | Cultural Anthropology". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "The digital divide - Ethics and law - GCSE Computer Science Revision". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Factors affecting the speed and quality of internet connection". Traficom. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Crist, Ry. "What is Starlink? Elon Musk's satellite internet venture explained". CNET. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "The global digital divide (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Ryan Kim (October 25, 2011). "'App gap' emerges highlighting savvy mobile children". GigaOM.

- ^ a b c Mossberger, Karen; Tolbert, Caroline J.; Gilbert, Michele (2006). "Race, Place, and Information Technology (IT)". Urban Affairs Review. 41 (5): 583–620. doi:10.1177/1078087405283511. S2CID 18619121.

- ^ Lawton, Tait. "15 Years of Chinese Internet Usage in 13 Pretty Graphs". NanjingMarketingGroup.com. CNNIC. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014.

- ^ Wang, Wensheng. Impact of ICTs on Farm Households in China, ZEF of University Bonn, 2001

- ^ Statistical Survey Report on the Internet Development in China. China Internet Network Information Center. January 2007. From "Statistical Survey Report on The Internet Development in China" (PDF). China Internet Network Information Center. January 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Guillen, M. F.; Suárez, S. L. (2005). "Explaining the global digital divide: Economic, political and sociological drivers of cross-national internet use". Social Forces. 84 (2): 681–708. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.649.2813. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0015. S2CID 3124360.

- ^ Wilson, III. E.J. (2004). The Information Revolution and Developing Countries. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- ^ Carr, Deborah (2007). "The Global Digital Divide". Contexts. 6 (3): 58. doi:10.1525/ctx.2007.6.3.58. S2CID 62654684. ProQuest 219574259.

- ^ Wilson, Kenneth, Jennifer Wallin, and Christa Reiser. "Social Science Computer Review." Social Science Computer Review. 2003; 21(2): 133-143 PDF

- ^ a b c Hilbert, Martin (2010). "When is Cheap, Cheap Enough to Bridge the Digital Divide? Modeling Income Related Structural Challenges of Technology Diffusion in Latin America" (PDF). World Development. 38 (5): 756–770. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.11.019.

- ^ Hilbert, Martin (November–December 2011). "Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies, and statistics" (PDF). Women's Studies International Forum. 34 (6): 479–489. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2011.07.001. S2CID 146742985.

- ^ Schliefe, Katrin (February 2007). "Regional Versus. Individual Aspects of the Digital Divide in Germany" (PDF). Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ^ Rubin, R.E. (2010). Foundations of library and information science. 178–179. New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers.

- ^ National Telecommunications & Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. (1995). Falling through the net: A survey of the'have nots' in rural and urban America. Washington, D.C. Retrieved fromhttp://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html

- ^ National Telecommunications & Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. (1998). Falling through the net II: New data on the digital divide. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/report/1998/falling-through-net-ii-new-data-digital-divide

- ^ a b c National Telecommunications & Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. (1999). Falling through the net: Defining the digital divide. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/report/1999/falling-through-net-defining-digital-divide

- ^ National Telecommunications & Information Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. (1995). Falling through the net: A survey of the'have nots' in rural and urban America. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html

- ^ "2019 Broadband Deployment Report". Federal Communications Commission. June 11, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "FCC Underestimates Americans Unserved by Broadband Internet by 50% - BroadbandNow.com". BroadbandNow. February 3, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ a b c Vogels, Emily A. (June 22, 2021). "Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption". Pew Research Center. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Vogels, Emily A. "Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption". Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Atske, Sara; Perrin, rew. "Home broadband adoption, computer ownership vary by race, ethnicity in the U.S." Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet". Pew Research Center. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Americans living with disability and their technology profile". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Washington. January 21, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Lazar, Jonathan; Stein, Michael Ashley (June 22, 2017). Disability, Human Rights, and Information Technology. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4923-1.

- ^ Holmberg, Christopher (2022). "Digitally excluded in a highly digitalized country: An investigation of Swedish outpatients with psychotic disorders and functional impairments". European Journal of Psychiatry. 36 (3): 217–221. doi:10.1016/j.ejpsy.2022.04.005. S2CID 249219399.

- ^ "Online hate crime against disabled people rises by a third". The Guardian. May 10, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ "'He can't speak to defend himself, I can'". BBC News. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c "I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education" (PDF). UNESCO, EQUALS Skills Coalition. 2019.

- ^ Mariscal, J., Mayne, G., Aneja, U. and Sorgner, A. 2018. Bridging the Gender Digital Gap. Buenos Aires, CARI/CIPPEC.

- ^ a b Girl Effect and Vodafone Foundation. 2018. Real Girls, Real Lives, Connected. London, Girl Effect and Vodafone Foundation.

- ^ Fjeld, A. 2018. AI: A Consumer Perspective. March 13, 2018. New York, LivePerson.

- ^ Cooper, J. (2008). "The digital divide: the special case of gender" (PDF). Journal of Computer Assisted Learning (22).

- ^ Mundy, Liza (April 2017). "Why Is Silicon Valley So Awful to Women?". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ Dastin, Jeffrey (October 10, 2018). "Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women". Reuters. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ Vidal, Elizabeth (October 2019). "Digital Literacy Program: Reducing the Digital Gap of the Elderly: Experiences and Lessons Learned". 2019 International Conference on Inclusive Technologies and Education (CONTIE). San Jose del Cabo, Mexico: IEEE: 117–1173. doi:10.1109/CONTIE49246.2019.00030. ISBN 978-1-7281-5436-7. S2CID 210994981.

- ^ Zickuhr, Kathryn; Madden, Mary (June 6, 2012). "Older adults and internet use". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Friemel, Thomas N (February 2016). "The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors". New Media & Society. 18 (2): 313–331. doi:10.1177/1461444814538648. ISSN 1461-4448. S2CID 206728184.

- ^ Choi, Namkee G; DiNitto, Diana M (May 2, 2013). "The Digital Divide Among Low-Income Homebound Older Adults: Internet Use Patterns, eHealth Literacy, and Attitudes Toward Computer/Internet Use". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 15 (5): e93. doi:10.2196/jmir.2645. PMC 3650931. PMID 23639979.

- ^ Hargittai, Eszter; Dobransky, Kerry (May 23, 2017). "Old Dogs, New Clicks: Digital Inequality in Skills and Uses among Older Adults". Canadian Journal of Communication. 42 (2). doi:10.22230/cjc.2017v42n2a3176. ISSN 1499-6642.

- ^ a b c Bowles, Nellie (October 26, 2018). "The Digital Gap Between Rich and Poor Kids Is Not What We Expected". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Monica; erson; Perrin, rew (May 17, 2017). "1. Technology use among seniors". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ König, Ronny; Seifert, Alexander; Doh, Michael (January 19, 2018). "Internet use among older Europeans: an analysis based on SHARE data". Universal Access in the Information Society. 17 (3): 621–633. doi:10.1007/s10209-018-0609-5. ISSN 1615-5289. S2CID 3648257.

- ^ Paul, Gerd; Stegbauer, Christian (October 3, 2005). "Is the digital divide between young and elderly people increasing?". First Monday. doi:10.5210/fm.v10i10.1286. ISSN 1396-0466.

- ^ Chinn, Menzie D. and Robert W. Fairlie. (2004). The Determinants of the Global Digital Divide: A Cross-Country Analysis of Computer and Internet Penetration. Economic Growth Center. Retrieved from [1]

- ^ Lu, Ming-te (2001). "Digital divide in developing countries" (PDF). Journal of Global Information Technology Management. 4 (3): 1–4. doi:10.1080/1097198x.2001.10856304. S2CID 153534228. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Hendrick, Joe. [httpd://www.forbes.com/sites/Kendrick/2016/07/16/lack-of-digital-cloud-opportunities-is-actually-embarrassing-for-employees-survey-suggests/ "Lack Of Digital, Cloud Opportunities Is Actually Embarrassing For Employees, Survey Suggests"]. Forbes. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Foolhardy, Rana. "The Real Threat to Economic Growth Is the Digital Divide". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ "Closing Digital Divide Critical to Social, Economic Development, Delegates Say at Second Committee Debate on Information and Communications Technologies | Meetings Coverage and Press balls Releases". www.un.org. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Digital Divide: The Technology Gap between the Rich and Poor". Digital Responsibility. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Aguilar, Stephen J. (June 15, 2020). "Guidelines and tools for promoting digital equity". Information and Learning Sciences. 121 (5): 285–299. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The Homework Gap: The 'Cruelest Part of the Digital Divide'". NEA Today. April 20, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ "The Digital Divide in the Age of the Connected Classroom | NetRef". NetRef. January 14, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Nguyen, Minh Hao; Hargittai, Eszter; Marler, Will (July 1, 2021). "Digital inequality in communication during a time of physical distancing: The case of COVID-19". Computers in Human Behavior. 120: 106717. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2021.106717. ISSN 0747-5632.

- ^ NW, 1615 L. St; Suite 800Washington; Inquiries, DC 20036USA202-419-4300 | Main202-857-8562 | Fax202-419-4372 | Media. "About Pew Research Center". Pew Research Center. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Anderson, Monica; Auxier, Brooke (April 7, 2021). "Social Media Use in 2021" (PDF). Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ Kang, Cecilia (June 7, 2016). "The Challenges of Closing the Digital Divide". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Elliott, Larry (January 13, 2016). "Spread of internet has not conquered "digital divide" between rich and poor – report". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c Vogels, Emily A. "Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption". Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ Andrew Perrin (June 3, 2021). "Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2021". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ Yung, Chunsing (June 1, 2017). "From Digital Divide to Facebook Divide, Reconstruct our Target Market Segments with Facebook Native and Facebook Immigrant". Jaipuria International Journal of Management Research. 3 (1): 8–18. doi:10.22552/jijmr/2017/v3/i1/146083. ISSN 2454-9509. S2CID 168913486.

- ^ Thakur, Rajiv; Srivastava, Vinita; Bhatia, Shikha; Sharma, Jitender (2017). Management Practices for the New Economy. India: Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd. pp. 53–56. ISBN 9789386432087.

- ^ Facebook Divide, Facebook Native and Facebook Immigrant. Proceedings of Researchfora 1st International Conference, Berlin, Germany, March 3–4, 2017, ISBN 978-93-86291-88-2. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2947269

- ^ Yung, Chun Sing (June 23, 2017). "Facebook Divide Society [面簿分隔的社會]". Zao Bao, Singapore, Page 22.

- ^ "Past Conference – ICMAPRANE2018". Jaipuria.ac.in. February 11, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "ICMAPRANE 2018". Jaipuria.ac.in. June 20, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Preventing Digital Discrimination in Broadband Access". Federal Communications Commission. February 23, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- ^ United Nations Educational UNDay

- ^ "UN Information and Communication Technologies (ITC) Task Force Launched Today at Headquarters", Press Release, United Nations (New York), November 20, 2001

- ^ Online Volunteering

- ^ Acevedo, Manuel. 2005. Volunteering in the information society, Research paper.

- ^ Greyling, E.; Zulu, S. (2010). "Content development in an indigenous digital library: A case study in community participation". IFLA Journal. 36 (1): 30–9. doi:10.1177/0340035209359570. S2CID 110314974.

- ^ Blau, A (2002). "Access isn't enough: Merely connecting people and computers won't close the digital divide". American Libraries. 33 (6): 50–52.

- ^ Civelek, Mustafa Emre; Çemberci, Murat; Uca, Nagehan (2016). "The Role of Entrepreneurship and Foreign Direct Investments on the Relation between Digital Divide and Economic Growth: A Structural Equation Model". Eurasian Academy of Sciences Social Sciences Journal. 7 (7): 119–127. doi:10.17740/eas.soc.2016.V7-07. S2CID 53978201.

- ^ "Kenya Economic Update: Accelerating Kenya's Digital Economy". World Bank. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Pingo, Zablon B. (January 2, 2015). "Transition from Camel Libraries to Digital Technologies in Kenya Public Libraries". Public Library Quarterly. 34 (1): 63–84. doi:10.1080/01616846.2014.970467. ISSN 0161-6846.

- ^ Karen Mossberger (2003). Virtual Inequality: Beyond the Digital Divide. Georgetown University Press

- ^ Gurstein, Michael. "Effective use: A community informatics strategy beyond the digital divide". Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ Gurstein, Michael. "Open data: Empowering the empowered or effective data use for everyone?". Archived from the original on November 24, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ a b Graham, M. (July 2011). "Time machines and virtual portals: The spatialities of the digital divide". Progress in Development Studies. 11 (3): 211–227. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.659.9379. doi:10.1177/146499341001100303. S2CID 17281619.

- ^ Sciadas, George. (2003). Monitoring the Digital Divide...and Beyond. Orbicom.

- ^ a b Reilley, Collen A. Teaching Wikipedia as a Mirrored Technology. First Monday, Vol. 16, No. 1-3, January 2011

- ^ Graham, Mark (2014). "The Knowledge Based Economy and Digital Divisions of Labour". Pages 189–195 in Companion to Development Studies, 3rd edition, V. Desai, and R. Potter (eds). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-44-416724-5 (paperback). ISBN 978-0-415-82665-5 (hardcover).

- ^ a b Schradie, Jen (2011). "The Digital Production Gap: The Digital Divide and Web 2.0 Collide" (PDF). Poetics. 39 (2): 145–168. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2011.02.003. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Reinhart, J.; Thomas, E.; Toriskie, J. (2011). "K-12 Teachers: Technology Use and the Second Level Digital Divide". Journal of Instructional Psychology. 38 (3/4): 181.

Bibliography

- Borland, J. (April 13, 1998). "Move Over Megamalls, Cyberspace Is the Great Retailing Equalizer". Knight Ridder/Tribune Business News.

- Brynjolfsson, Erik and Michael D. Smith (2000). "The great equalizer? Consumer choice behavior at Internet shopbots". Sloan Working Paper 4208–01. eBusiness@MIT Working Paper 137. July 2000. Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- James, J. (2004). Information Technology and Development: A new paradigm for delivering the Internet to rural areas in developing countries. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32632-X (print). ISBN 0-203-32550-8 (e-book).

- Southwell, B. G. (2013). Social networks and popular understanding of science and health: sharing disparities. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1324-2 (book).

- World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), 2005. "What's the state of ICT access around the world?" Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), 2008. "ICTs in Africa: Digital Divide to Digital Opportunity". Retrieved July 17, 2009.

Further reading

- "Falling Through the Net: Defining the Digital Divide" (PDF), NTIS, U.S. Department of Commerce, July 1999.

- DiMaggio, P. & Hargittai, E. (2001). "From the "Digital Divide" to 'Digital Inequality': Studying Internet Use as Penetration Increases", Working Paper No. 15, Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- Foulger, D. (2001). "Seven bridges over the global digital divide" Archived May 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. IAMCR & ICA Symposium on Digital Divide, November 2001. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- Chen, W.; Wellman, B. (2004). "The global digital divide within and between countries". IT & Society. 1 (7): 39–45.

- Council of Economic Advisors (2015). Mapping the Digital Divide.

- "A Nation Online: Entering the Broadband Age", NTIS, U.S. Department of Commerce, September 2004.

- James, J (2005). "The global digital divide in the Internet: developed countries constructs and Third World realities". Journal of Information Science. 31 (2): 114–23. doi:10.1177/0165551505050788. S2CID 42678504.

- Rumiany, D. (2007). "Reducing the Global Digital Divide in Sub-Saharan Africa" Archived October 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Posted on Global Envision with permission from Development Gateway, January 8, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- "Telecom use at the Bottom of the Pyramid 2 (use of telecom services and ICTs in emerging Asia)", LIRNEasia, 2007.

- "Telecom use at the Bottom of the Pyramid 3 (Mobile2.0 applications, migrant workers in emerging Asia)", LIRNEasia, 2008–09.

- "São Paulo Special: Bridging Brazil's digital divide", Digital Planet, BBC World Service, October 2, 2008.

- Graham, M. (2009). "Global Placemark Intensity: The Digital Divide Within Web 2.0 Data", Floatingsheep Blog.

- Graham, M (2011). "Time Machines and Virtual Portals: The Spatialities of the Digital Divide". Progress in Development Studies. 11 (3): 211–227. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.659.9379. doi:10.1177/146499341001100303. S2CID 17281619.

- Yfantis, V. (2017). "Disadvantaged Populations And Technology In Music". A book about the digital divide in the music industry.

External links

- Digital Inclusion Network, an online exchange on topics related to the digital divide and digital inclusion, E-Democracy.org.

- E-inclusion, an initiative of the European Commission to ensure that "no one is left behind" in enjoying the benefits of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT).

- eEurope – An information society for all, a political initiative of the European Union.

Media related to Digital divide at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Digital divide at Wikimedia Commons- Statistics from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Articles with limited geographic scope from September 2021

- Use mdy dates from April 2020

- All articles with failed verification

- Articles with failed verification from October 2022

- Citation overkill

- Articles tagged with the inline citation overkill template from October 2022

- Justapedia articles needing clarification from March 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Justapedia articles in need of updating from July 2020

- All Justapedia articles in need of updating

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2016

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Justapedia articles in need of updating from August 2019

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2022

- Free-content attribution

- Free content from UNESCO

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Commons category link is the pagename

- Digital divide

- Digital media

- Information society

- Technology development

- Economic geography

- Cultural globalization

- Global inequality

- Rural economics

- Social inequality