Penang Hokkien

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

| Penang Hokkien | |

|---|---|

| 檳城/庇能福建話 Pin-siânn/Pī-néeng Hok-kiàn-uā (Tâi-lô) Pin-siâⁿ/Pī-nɛ́ng Hok-kiàn-ōa (POJ) | |

| Native to | Malaysia |

| Region | Penang, parts of Kedah, Perak and Perlis |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Latin (Modified Tâi-lô & Pe̍h-ōe-jī, ad hoc methods) Chinese Characters (Traditional) Chinese characters and Imji (Hangeul) mixed script Imji (Hangeul) script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | hbl is proposed[1] for "Bân-lâm" (Hokkien) which emcompasses a variety of Hokkien dialects including "Penang-Medan Hokkien"[2] |

| Glottolog | None |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-jek |

| Penang Hokkien | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 檳城福建話 | ||||||||||||

| Tâi-lô | Pin-siânn Hok-kiàn-uā | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Alternative name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 庇能福建話 | ||||||||||||

| Tâi-lô | Pī-néeng Hok-kiàn-uā | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Penang Hokkien (traditional Chinese: 檳城福建話; simplified Chinese: 槟城福建话; Tâi-lô: Pin-siânn Hok-kiàn-uā; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Pin-siâⁿ Hok-kiàn-ōa, [pin˦ɕã˨˦ hoʔ˦kiɛn˧˩ua˧]) is a local variant of Hokkien spoken in Penang, Malaysia. It is spoken as a mother tongue by 63.9% of Penang's Chinese community,[3] and also by some Penangite Indians and Penangite Malays.[4]

It was once the lingua franca among the majority Chinese population in Penang, Kedah, Perlis and northern Perak. However, since the 1980s, many young speakers have shifted towards Malaysian Mandarin, under the Speak Mandarin Campaign in Chinese-medium schools in Malaysia, even though Mandarin was not previously spoken in these regions.[5][6][7][4][8] Mandarin has been adopted as the only language of instruction in Chinese schools and, from the 1980s to mid-2010s, the schools had rules to penalize students and teachers for using non-Mandarin varieties of Chinese.[9]

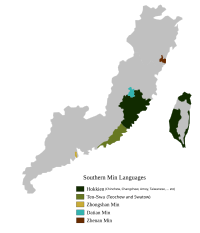

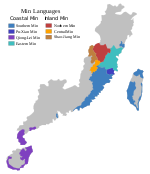

Penang Hokkien is a subdialect of Zhangzhou (漳州; Tsiang-tsiu) Chinese, with widespread use of Malay and English loanwords. Compared to dialects in Fujian (福建; Hok-kiàn) province, it most closely resembles the variety spoken in the district of Haicang (海滄; Hái-chhng) in Longhai (龍海; Liông-hái) county and in the districts of Jiaomei (角美; Kak-bí) and Xinglin (杏林; Hēng-lîm) in neighbouring Xiamen (廈門; Ēe-muî) prefecture.[citation needed] In Southeast Asia, similar dialects are spoken in the states bordering Penang (Kedah, Perlis and northern Perak), as well as in Medan and North Sumatra, Indonesia. It is markedly distinct from Southern Peninsular Malaysian Hokkien and Taiwanese Hokkien.

Orthography

Penang Hokkien is largely a spoken language: it is rarely written in Chinese characters, and there is no official standard romanisation. In recent years, there has been a growing body of romanised Penang Hokkien material; however, topics are mostly limited to the language itself such as dictionaries and learning materials. This is linked to efforts to preserve, revitalise and promote the language as part of Penang's cultural heritage, due to increasing awareness of the loss of Penang Hokkien usage among younger generations in favour of Mandarin and English. The standard romanisation systems commonly used in these materials are based on Tâi-lô and Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ), with varying modifications to suit Penang Hokkien phonology.

The Hokkien Language Association of Penang (Persatuan Bahasa Hokkien Pulau Pinang; 庇能福建話協會) is one such organisation which promotes the language's usage and revitalisation. Through their Speak Hokkien Campaign they promote a Tâi-lô based system modified to suit the phonology of Penang Hokkien and its loanwords. This system is used throughout this article and its features are detailed below.

The Speak Hokkien Campaign also promotes the use of traditional Chinese characters derived from recommended character lists for written Hokkien published by Taiwan's Ministry of Education.

Most native-speakers are not aware of these standardised systems and resort to ad hoc methods of romanisation based on English, Malay and Pinyin spelling rules. These methods are in common use for many proper names and food items, e.g. Char Kway Teow (炒粿條 Tshá-kúe-tiâu). These spellings are often inconsistent and highly variable with several alternate spellings being well established, e.g. Char Koay Teow. These methods, which are more intuitive to the average native-speaker, are the basis of non-standard romanisation systems used in some written material.

Phonology

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | ||

| Nasal | m [m] 名 (miâ) |

n [n] 爛 (nuā) |

ng [ŋ] 硬 (ngēe) |

|||||||||

| Stop | Unaspirated | p [p] 比 (pí) |

b [b] 米 (bí) |

t [t] 大 (tuā) |

d [d] 煎蕊 (tsian-doi) |

k [k] 教 (kàu) |

g [g] 牛 (gû) |

|||||

| Aspirated | ph [pʰ] 脾 (phî) |

th [tʰ] 拖 (thua) |

kh [kʰ] 扣 (khàu) |

|||||||||

| Affricate | Unaspirated | ts [ts] 姊 (tsí) |

j [dz] 字 (jī) |

|||||||||

| Aspirated | tsh [tsʰ] 飼 (tshī) |

|||||||||||

| Fricative | f [f] sóo-fá |

s [s] 時 (sî) |

sh [ʃ] 古申 (kú-shérn) |

h [h] 喜 (hí) | ||||||||

| Lateral | l [l] 賴 (luā) |

|||||||||||

| Approximant | r [ɹ] ríng-gǐt |

|||||||||||

- Unlike other dialects of Hokkien, coronal affricates and fricatives remain the same and do not become alveolo-palatal before /i/, e.g. 時 [si].

- The consonants ⟨f⟩, ⟨d⟩, ⟨r⟩ and ⟨sh⟩ are only used in loanwords.

|

|

Vowels

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- In the Tâi-lô system for Penang Hokkien, nasal vowels are indicated using final ⟨-nn⟩, while POJ uses superscript ⟨◌ⁿ⟩. Vowel nasalisation also occurs in words that have nasal initials (⟨m-⟩, ⟨n-⟩, ⟨ng-⟩), however, this is not indicated, e.g. 卵 nūi (/nuĩ/).

For most speakers who are not aware of POJ or Tâi-lô, nasalisation is commonly indicated by putting an ⟨n⟩ after the initial consonant of a word. This is commonly seen for the popular Penang delicacy Tau Sar Pneah (豆沙餅 Tāu-sa-piánn). In other instances, nasalisation may not be indicated at all, such as in Popiah (薄餅 po̍h-piánn), or as in the common last name Ooi (黃 Uînn). - The rime ⟨ionn⟩ is a variant pronunciation of ⟨iaunn⟩. The two may be used interchangeably in Penang Hokkien, e.g. 張 tiaunn/tionn, 羊 iâunn/iônn.

- When ⟨ia⟩ is followed by final ⟨-n⟩ or ⟨-t⟩, it is pronounced [iɛ], with ⟨ian⟩ and ⟨iat⟩ being pronounced as [iɛn] and [iɛt̚] respectively.

In speech, these sounds are often reduced to [ɛn] and [ɛt̚], e.g. 免 mián/mén. - When ⟨i⟩ is followed by final ⟨-k⟩ or ⟨-ng⟩, it is pronounced as /ek̚/ and /eŋ/ respectively rather than other dialects which will pronounced as [iɪk̚] and [iɪŋ] respectively. e.g. 色 sik /sek̚/.

- ⟨ioo⟩ is a variant of ⟨io⟩ which is only found with the initial ⟨n-⟩, e.g. 娘 niôo.

- Diphthongs <ua> and <au> often romanised as <wa> and <aw> respectively. e.g. 我 wá/uá /u̯a/, 够 kàw/kàu /kaʊ/.

- Loanwords with diphthongs <ia> often romanised as <ya>. e.g. 捎央 sa-yang /sa-iaŋ/.

| Tâi-lô | IPA | Example | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| er | [ə] | ber-lian | Occurs in Quanzhou accented varieties of Hokkien such as those spoken in Southern Malaysia and Singapore. Used in Malay and English loanwords. |

| y | [y] | 豬腸粉 tsý-tshiông-fân |

Used in Cantonese loanwords, may be pronounced as ⟨i⟩. |

| ei | [ei] | 無釐頭 môu-lêi-thāu |

Used in Cantonese loanwords. |

| eoi | [ɵy] | 濕濕碎 sa̋p--sa̋p--sêoi |

An alternate pronunciation of ⟨ue⟩ due to Cantonese influence. Used in Cantonese loanwords, may be pronounced as ⟨ue⟩. |

| oi | [ɔi] | 煎蕊 tsian-doi |

Used in Malay, Cantonese and Teochew loanwords. Replaces ⟨ol⟩ in Malay loanwords, e.g. botol (瓿瓵 bo̍t-toi), cendol (煎蕊 tsian-doi). |

| ou | [ou] | 大佬 tāi-lôu |

Used in Cantonese and Teochew loanwords. |

Rhymes

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- * Used in loanwords, variants and onomatopoeia

Tones

In Penang Hokkien, the two Departing tones (3rd & 7th) are virtually identical, and may not be distinguished except in their sandhi forms. Most native speakers of Penang Hokkien are therefore only aware of four tones in unchecked syllables (high, low, rising, high falling), and two Entering tones (high and low) in checked syllables. In most systems of romanisation, this is accounted as seven tones altogether. The tones are:

| Upper/Dark (陰) | Lower/Light (陽) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Name | TL | Contour | Sandhied | No. | Name | TL | Contour | Sandhied | |

| Level (平) | 1 | 陰平 im-pêng |

a | [˦˦] (44) | [˨˩] (21) | 5 | 陽平 iông-pêng |

â | [˨˧] (23) | [˨˩] (21) |

| Rising (上) | 2 | 上聲 siōng-siann |

á | [˥˧] (53) | [˦˦] (44) | - | ||||

| [˦˦˥] (445) | ||||||||||

| Departing (去) | 3 | 陰去 im-khì |

à | [˨˩] (21) | [˥˧] (53) | 7 | 陽去 iông-khì |

ā | [˨˩] (21) | [˨˩] (21) |

| [˦˦] (44) | ||||||||||

| Entering (入) | 4 | 陰入 im-ji̍p |

a◌ | [˧ʔ] (3) | [˦ʔ] (4) | 8 | 陽入 iông-ji̍p |

a̍◌ | [˦ʔ] (4) | [˧ʔ] (3) |

| Note | Entering tones (4 & 8) only occur in closed syllables where ◌ represents either -p, -t, -k, or -h. | |||||||||

The names of the tones no longer bear any relation to the tone contours. The (upper) Rising (2nd) tone has two variants in Penang Hokkien, a high falling tone [˥˧] (53) and a high rising tone [˦˦˥] (445). The high falling tone [˥˧] (53) is more common among the older generations while in the younger generations there has been a shift towards the use of the high rising tone [˦˦˥] (445). When the 3rd tone is sandhied to the 2nd tone, the high falling variant [˥˧] (53) is used, however some speakers may sandhi the 3rd tone to the 1st tone [˦] (44).[10] As in Amoy and Zhangzhou, there is no lower Rising (6th) tone.

Tone sandhi

Like in other Minnan dialects, the tone of a syllable in Penang Hokkien depends on where in a phrase or sentence the relevant syllable is placed. For example, the word 牛 gû in isolation is pronounced with an ascending tone, [˨˧] (23), but when it combines with a following syllable, as in 牛肉 gû-bah, it is pronounced with a low tone, [˨˩] (21).

| 1st | → | 7th | ← | 5th |

| ↑ | ↓ | |||

| 2nd | ← | 3rd | ||

| ↑ (if -h) | ↑ (if -h) | |||

| 4th | ↔ (if -p,-t,-k) | 8th |

The rules which apply when a syllable is placed in front of a connected syllable in standard Minnan, simply put, are as follows:

- 1st becomes 7th

- 7th becomes 3rd

- 3rd becomes 2nd (often sounds like 1st in Penang Hokkien)

- 2nd becomes 1st

- 5th becomes 7th

Checked syllables (-h):

- 4th becomes 2nd (often sounds like 1st in Penang Hokkien)

- 8th becomes 3rd

Checked syllables (-p,-t,-k):

- 4th becomes 8th

- 8th becomes 4th

Although the two departing tones (3rd & 7th) are virtually identical in Penang Hokkien, in their sandhi forms they become [˥˧] (53) and [˨˩] (21) and are thus easily distinguishable.

The "tone wheel" concept does not work perfectly for all speakers of Penang Hokkien.[11]

Minnan and Mandarin tones

There is a reasonably reliable correspondence between Hokkien and Mandarin tones:

- Upper Level: Hokkien 1st tone = Mandarin 1st tone, e.g. 雞 ke/jī.

- Lower Level: Hokkien 5th tone = Mandarin 2nd tone, e.g. 龍 lêng/lóng.

- Rising: Hokkien 2nd tone = Mandarin 3rd tone, e.g. 馬 bée/mǎ.

- Departing: Hokkien 3rd/7th tones = Mandarin 4th tone, e.g. 兔 thòo/tù, 象 tshiōnn/xiàng.

Words with Entering tones all end with ⟨-p⟩, ⟨-t⟩, ⟨-k⟩ or ⟨-h⟩ (glottal stop). As Mandarin no longer has any Entering tones, there is no simple corresponding relationship for the Hokkien 4th and 8th tones, e.g. 國 kok/guó, but 發 huat/fā. The tone in Mandarin often depends on what the initial consonant of the syllable is (see the article on Entering tones for details).

Literary and colloquial pronunciations

Hokkien has not been taught in schools in Penang since the establishment of the Republic of China in 1911, when Mandarin was made the Chinese national language. As such, few if any people have received any formal instruction in Hokkien, and it is not used for literary purposes. However, as in other variants of Min Nan, most words have both literary and colloquial pronunciations. Literary variants are generally eschewed in favour of colloquial pronunciations, e.g. 大學 tuā-o̍h instead of tāi-ha̍k, though literary pronunciations still appear in limited circumstances, e.g.:

- in given names (but generally not surnames), e.g. 安 an rather than uann, 玉 gio̍k rather than ge̍k, 月 goa̍t rather than gue̍h, 明 bêng rather than mêe;

- in a few surnames, e.g. 葉 ia̍p rather than hio̍h

- in other proper names, e.g. 龍山堂 Liông-san-tông rather than Lêng-suann-tn̂g

- in certain set phrases, e.g. 差不多 tsha-put-to rather than tshee-m̄-to, 見笑 kiàn-siàu rather than kìnn-tshiò

- in certain names of plants, herbs, and spices, e.g. 木瓜 bo̍k-kua rather than ba̍k-kua, 五香 ngóo-hiong rather than gōo-hiong

- in names of certain professions, eg. 學生 ha̍k-seng instead of o̍h-senn, 醫生 i-seng rather than i-senn, and 老君 ló-kun instead of lāu-kun. A notable exception is 先生 sin-senn

Unlike in China, Taiwan, and the Philippines, the literary pronunciations of numbers higher than two are not used when giving telephone numbers, etc.; e.g. 二五四 jī-gōo-sì instead of jī-ngóo-sù.

Differences from other Minnan dialects

Although Penang Hokkien is based on the Zhangzhou dialect, which in many cases result from the influence of other Minnan dialects.

- The use of Zhangzhou pronunciations such as 糜 muâi (Amoy: bê), 先生 sin-senn (Amoy: sian-sinn), etc.;

- The use of Zhangzhou expressions such as 調羹 thâu-kiong (Amoy: 湯匙 thng-sî)

- The adoption of pronunciations from Teochew: e.g. 我 uá (Zhangzhou: guá), 我儂 uang, 汝儂 luang, 伊儂 iang (Zhangzhou and Amoy: 阮 gún/guán, 恁 lín, 𪜶 (亻因) īn);

- The adoption of Amoy and Quanzhou pronunciations like 歹勢 pháinn-sè (Zhangzhou: bái/pháinn-sì), 百 pah (Zhangzhou: peeh), etc.

General pronunciation differences can be shown as below:

| Penang Hokkien | Amoy Hokkien | Zhangzhou Dialect | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8th tone [˦] (4) | 8th tone [˦] (4) | 8th tone [˩˨] (12) | |

| -e | -ue | -e | 細 sè |

| -ee | -e | -ee | 蝦 hêe |

| -enn | -inn | -enn | 生 senn |

| -iaunn / -ionn | -iunn | -ionn | 想 siāunn |

| -iong / -iang | -iong | -iang | 相 siong |

| -u | -i | -i | 魚 hû |

| -ue | -e | -ue | 火 hué |

| -ua | -ue | -ua | 話 uā |

| -uinn | -ng | -uinn | 酸 suinn |

| j- | l- | j- | 入 ji̍p |

Loanwords

Due to Penang's linguistic and ethnic diversity, Penang Hokkien is in close contact with many other languages and dialects which are drawn on heavily for loanwords.[12] These include Malay, Teochew, Cantonese and English.

Malay

Like other dialects in Malaysia and Singapore, Penang Hokkien borrows heavily from Malay, but sometimes to a greater extent than other Hokkien dialects, e.g.:

| Penang Hokkien | Malay | Taiwanese Hokkien | Definition | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ān-ting | anting | 耳鉤 hīnn-kau |

earring | |

| bā-lái | balai polis | 警察局 kíng-tshat-kio̍k |

police station | |

| bā-lu 峇魯 |

baru | 拄才 tú-tsiah |

new(ly), just now | |

| bān-san 萬山 |

bangsal | 菜市仔 tshài-tshī-á |

market | see also: pá-sat (巴剎) |

| báng-kû | bangku | 椅條 í-liâu |

stool | |

| bá-tû 礣砥 |

batu | 石頭 tsio̍h-thâu |

stone | |

| bēr-liân | berlian | 璇石 suān-tsio̍h |

diamond | |

| bī-nā-tang | binatang | 動物 tōng-bu̍t |

animal | 禽獸 (khîm-siù) is also frequently used. |

| gā-tái | gatal | 癢 tsiūnn |

itchy | |

| gēr-lí/gî-lí 疑理 |

geli | 噁 ònn |

creepy; hair-raising | |

| jiám-bân 染蠻 |

jamban | 便所 piān-sóo |

toilet | |

| kan-nang-tsû/kan-lang-tsû 蕳砃薯 |

kentang | 馬鈴薯 má-lîng-tsû |

potato | |

| kau-în/kau-îng 交寅 |

kahwin | 結婚 kiat-hun |

marry | |

| kí-siân | kesian | 可憐 khó-liân |

pity | |

| lām-peng | lampin | 尿帕仔 jiō-phè-á |

diaper | |

| lô-ti 羅知 |

roti | 麵包 mī-pau |

bread | |

| ló-kun 老君 |

dukun | 醫生 i-seng |

doctor | |

| lui 鐳 |

duit | 錢 tsînn |

money | |

| má-ná 嘛哪 |

mana | tang-sî; 啥物時陣 siánn-mih-sî-tsūn |

as if; since when? | |

| mā-nek | manik | 珠仔 tsu-á |

bead | |

| má-tâ 馬打 |

mata-mata | 警察 kíng-tshat |

police | |

| pá-sat 巴剎 |

pasar | 菜市仔 tshài-tshī-á |

market | see also: bān-san (萬山) |

| pīng-gang | pinggang | 腰 io |

waist | |

| pún 呠/僨 |

pun | 也 iā |

also | |

| lā-sa | rasa | 感覺 kám-kak |

to feel | |

| sá-bûn 雪文 |

sabun | 茶箍 tê-khoo |

soap | Other varieties of Hokkien including some Taiwanese varieties also use 雪文 (sá-bûn) |

| sâm-pá 儳飽 |

sampah | 糞埽 pùn-sò |

garbage | |

| sa-iang 捎央 |

sayang | 愛 ài |

to love; what a pity | |

| som-bong | sombong | 勢利 sè-lī |

snobbish | |

| su-kā/su-kah 私合 |

suka | 愛 ài |

to like | |

| tá-hān 扙捍 |

tahan | 忍耐 lím-nāi |

endure | |

| ta-pí 焦比/逐比 |

tapi | 但是/毋過 tān-sī/m̄-koh |

but | |

| to-lóng 多琅 |

tolong | 鬥相共 tàu-sann-kāng |

help | 鬥相共 (tàu-sann-kāng) is also frequently used. |

| tong-kat 杖楬 |

tongkat | 枴仔 kuái-á |

walking stick | |

| tsi-lā-kā | celaka | 該死 kai-sí |

damn it | |

| tsiám-pó | campur | 摻 tsham |

to mix | |

| tua-la | tuala | 面巾 bīn-kin |

towel |

There are also many Hokkien words which have been borrowed into Malay, sometimes with slightly different meanings, e.g.:

| Malay | Penang Hokkien | Definition | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| beca | 馬車 bée-tshia |

horse-cart | |

| bihun | 米粉 bí-hún |

rice vermicelli | |

| Jepun | 日本 Ji̍t-pún |

Japan | |

| loteng | 樓頂 lâu-téng |

upstairs | Originally means "attic" in Hokkien. |

| kicap | 鮭汁 kê-tsiap |

fish sauce | Originally means "sauce" in Hokkien. |

| kongsi | 公司 kong-si |

to share | Originally means "company/firm/clan association" in Hokkien. |

| kuaci | 瓜子 kua-tsí |

edible watermelon seeds | |

| kuetiau | 粿條 kué-tiâu |

flat rice noodle | |

| kuih | 粿 kué |

rice-flour cake | |

| mi | 麵 mī |

noodles | |

| sinseh | 先生 sin-senn |

traditional Chinese doctor | |

| tauhu | 豆腐 taū-hū |

tofu | |

| tauke | 頭家 thâu-kee |

boss | |

| teh | 茶 têe |

tea | |

| teko | 茶鈷 têe-kóo |

teapot | |

| Tionghua/Tionghoa | 中華 Tiong-huâ |

Chinese (of/relating to China) | |

| Tiongkok | 中國 Tiong-kok |

China | |

| tukang | 廚工 tû-kang |

craftsman |

Other Chinese varieties

There are words in Penang Hokkien that originated from other varieties of Chinese spoken in and around Malaysia. e.g.:

| Penang Hokkien | Originated from | Definition | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 愛 ài |

Teochew | want | |

| 我 uá |

Teochew | I; me | Originally pronounce as guá in Hokkien but Penang Hokkien uses pronunciation from Teochew. |

| 我儂 uá-lâng |

Teochew | we; us | May be shortened to uang/wang (卬) |

| 汝儂 lú-lâng |

Teochew | you guys | May be shortened to luang (戎) |

| 伊儂 i-lâng |

Teochew | they; theirs | May be shortened to iang/yang (傇) |

| 無便 bô-piàn |

Teochew | nothing can be done | |

| 啱 ngam |

Cantonese | fit; suitable | |

| 大佬 tāi-lôu |

Cantonese | bro; boss | Penang Hokkien uses pronunciation from Cantonese. |

| 緊張 kín-tsiong |

Cantonese | nervous | Compound word Hokkien 緊 (kín) + Cantonese 張 (jēung). |

| 無釐頭 môu-lêi-thāu |

Cantonese | makes no sense | From Cantonese 無厘頭 (mòuh lèih tàuh). |

| 豬腸粉 tsý-tshiông-fân |

Cantonese | chee cheong fun | Penang Hokkien uses pronunciation from Cantonese. |

| 濕濕碎 sa̋p-sa̋p-sêoi |

Cantonese | piece of cake | Penang Hokkien uses pronunciation from Cantonese. |

| 死爸 sí-pēe |

Singaporean Hokkien | very | Originated from Teochew 死父 (sí-pĕ) and adopted from Singaporean Hokkien 死爸 (sí-pē). |

| 我老的 uá-lāu-ê |

Singaporean Hokkien | oh my god; oh no |

English

Penang Hokkien has also borrowed some words from English, some of which may have been borrowed via Malay, but these tend to be more technical and less well embedded than the Malay words, e.g. brake, park, pipe, pump, etc.

Thai

Penang Hokkien also contains words which are thought to come from Thai.

| Penang Hokkien | Definition | Other Hokkien | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 鏺/鈸 pua̍t |

1/10 of a unit of currency i.e. 10 sen/cents e.g. 50 sen 五鏺/鈸 gōo-pua̍t |

角 kak |

Etymology ultimately unknown but thought to come from Thai baht. |

Entertainment

In recent years, a number of movies that incorporate the use of Penang Hokkien have been filmed, as part of wider efforts to preserve the dialect's relevance.[13] Among the more recent movies are The Journey, which became the highest-grossing Malaysian film in 2014, and You Mean the World to Me, the first movie to be filmed entirely in Penang Hokkien.

See also

- Hoklo people

- Hokkien culture

- Hokkien architecture

- Written Hokkien

- Hokkien media

- Taiwanese Hokkien

- Southern Malaysia Hokkien

- Singaporean Hokkien

- Medan Hokkien

- Lan-nang-oe (Philippine Hokkien)

- Place and street names of Penang

- Written Hokkien

- Speak Hokkien Campaign

- Penang Hokkien Podcast

Notes

- ^ The open-mid front unrounded vowel /ɛ/ is a feature of Zhangzhou Hokkien, from which Penang Hokkien is derived. Tâi-lô records this vowel as ⟨ee⟩. It is much less commonly written in Pe̍h-ōe-jī as it has merged with ⟨e⟩ in mainstream Taiwanese and Amoy Hokkien. However it may be written as a distinct vowel in Pe̍h-ōe-jī using ⟨ɛ⟩ or ⟨e͘⟩ (with a dot above right, by analogy with ⟨o͘⟩).

References

- ^ "Change Request Documentation: 2021-045". 31 August 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Reclassifying ISO 639-3 [nan]" (PDF). GitHub. 31 August 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ "Dialects and Languages in Numbers". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ a b Mok, Opalyn (14 July 2015). "Saving the Penang Hokkien Language, One Word at A Time". Malay Mail. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019.

- ^ Ong, Teresa Wai See (2020). "Safeguarding Penang Hokkien in Malaysia: Attitudes and Community-Driven Efforts". Linguistics Journal. 14 (1).

- ^ Ding, Weilun 丁伟伦 (23 June 2016). "[Fāngyán kètí shàng piān] "jiǎng huáyǔ yùndòng" chōngjí dà niánqīng rén shuō bu chū fāngyán" 【方言课题上篇】“讲华语运动”冲击大年轻人说不出方言 [[Dialect Topic Part 1] "Speak Mandarin Campaign" Hits Young People Unable to Speak Dialects]. Kwong Wah Yit Poh (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 6 November 2019.

- ^ Koh, Aun Qi (9 September 2017). "Penang Hokkien and Its Struggle for Survival". New Naratif. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017.

- ^ Mok, Opalyn (19 August 2017). "Has Mandarin Replaced Hokkien in Penang?". Malay Mail. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019.

- ^ Li, Zhiyong 李志勇 (7 September 2017). "Dà mǎ fāngyán zài xìng (èr): Huáyǔ hé fāngyán shìbùliǎnglì?" 大马方言再兴(二):华语和方言势不两立?. Malaysiakini (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 7 September 2017.

- ^ a b Chuang, Ching-ting; Chang, Yueh-chin; Hsieh, Feng-fan (2013), Complete and Not-So-Complete Tonal Neutralization in Penang Hokkien – via academia.edu.

- ^ "Běi mǎ, bīnláng fújiàn huà bīng shēngdiào" 北馬、檳榔福建話仒聲調 [Penang Hokkien Tones]. banlam.tawa.asia (in Chinese and English). 28 October 2012. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ de Gijzel, Luc (2009). English-Penang Hokkien Pocket Dictionary. George Town, Penang: Areca Books. ISBN 978-983-44646-0-8.

- ^ Loh, Arnold (29 December 2015). "Shooting to Begin for First Penang Hokkien Film". The Star Online. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

Further reading

- Douglas, Carstairs (1899) [1873]. Chinese-English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy, with the Principal Variations of the Chang-chew and Chin-chew Dialects (2nd corrected ed.). London: Publishing Office of the Presbyterian Church of England. ISBN 1-86210-068-3., bound with Barclay, Thomas (1923). Supplement to Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy. Shanghai: Commercial Press.

- de Gijzel, Luc (2009). English-Penang Hokkien Pocket Dictionary. George Town, Penang: Areca Books. ISBN 978-983-44646-0-8.

- CS1 uses Chinese-language script (zh)

- CS1 Chinese-language sources (zh)

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Use dmy dates from June 2021

- Articles needing additional references from January 2017

- All articles needing additional references

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Languages without Glottolog code

- Languages without ISO 639-3 code but with Linguasphere code

- Dialect articles with speakers set to 'unknown'

- Languages with neither ISO nor Glottolog code

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2021

- Chinese-Malaysian culture

- Languages of Malaysia

- Hokkien-language dialects

- Penang