Malayan Emergency

| Malayan Emergency Darurat Malaya 馬來亞緊急狀態 மலாயா அவசரகாலம் | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the decolonization of Asia and Cold War in Asia | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Commonwealth forces:

Supported by: (Thai–Malaysian border) |

Communist forces:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Over 451,000 troops.

|

Over 7,000 troops.

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

6,710 killed 1,289 wounded 1,287 captured 2,702 surrendered | ||||||

|

Civilians killed: 2,478 Civilians missing: 810 Civilian casualties: 5,000+ Total killed: 11,053 | |||||||

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

| History of Singapore |

|---|

|

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War (1948–1960), was a guerrilla war fought in British Malaya between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) and the military forces of the British Empire and Commonwealth. The communists fought to win independence for Malaya from the British Empire and to establish a socialist economy, while the Commonwealth forces fought to combat communism and protect British economic and colonial interests.[1][2][3] The conflict was called the "Anti–British National Liberation War" by the MNLA,[4] but an "Emergency" by the British, as London-based insurers would not have paid out in instances of civil wars.[5]

On 17 June 1948, Britain declared a state of emergency in Malaya following attacks on plantations,[6] which in turn were revenge attacks for the killing of left-wing activists.[7] Leader of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) Chin Peng and his allies fled into the jungles and formed the MNLA to wage a war for national liberation against British colonial rule. Many MNLA fighters were veterans of the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), a communist guerrilla army previously trained, armed and funded by the British to fight against Japan during World War II.[8] The communists gained support from a high number of civilians, mainly those from the Chinese community.[9]

After establishing a series of jungle bases the MNLA began raiding British colonial police and military installations. Mines, plantations, and trains were attacked by the MNLA to gain independence for Malaya by bankrupting the British occupation. The British attempted to starve the MNLA using scorched earth policies through food rationing, killing livestock, and aerial spraying of the herbicide Agent Orange.[15] British attempts to defeat the communists included extrajudicial killings of unarmed villagers, in violation of the Geneva Conventions.[16] The most infamous example is the Batang Kali massacre, which the British press have referred to as "Britain's Mỹ Lai".[21] The Briggs Plan forcibly relocated 400,000 to one million civilians into concentration camps, which were referred to by the British as "New villages".[22][23][24] Many Orang Asli indigenous communities were also targeted for internment because the British believed that they were supporting the communists.[25][26] The communists' belief in class consciousness, and both ethnic and gender equality, inspired many women and indigenous people to join both the MNLA and its undercover supply network the Min Yuen.[27]

Although the emergency was declared over in 1960, communist leader Chin Peng renewed the insurgency against the Malaysian government in 1967. This second phase of the insurgency lasted until 1989.

Origins

Socioeconomic issues

At the end of World War II, the withdrawal of Japan left the British Malayan economy disrupted with widespread unemployment, low wages, and high levels of food price inflation. The weak economy was a factor in the growth of trade union movements and caused a rise in communist party membership, with considerable labour unrest and a large number of strikes occurred between 1946 and 1948.[28] Malayan communists organised a successful 24-hour general strike on 29 January 1946,[29] before organising 300 strikes in 1947.[29] To combat rising trade union activity the British used police and soldiers as strikebreakers, and employers enacted mass dismissals, forced evictions of striking workers from their homes, legal harassement, and began cutting the wages of their workers.[28] Colonial police responded to rising trade union activity through arrests, deportations, and beating striking workers to death.[30] Responding to the attacks against trade unions, communist militants began assassinating strikebreakers, and attacking anti-union estates.[30] These attacks were used by the colonial occupation as a pretence to conduct mass arrests of left-wing activists.[28] On 12 June the British colonial occupation banned Malaya's largest trade union the PMFTU.[30]

Malaya's rubber and tin resources were used by the British to pay war debts to the United States and to recover from the damage of the second world war.[30] Malaysian rubber exports to the United States were of greater value than all domestic exports from Britain to America, causing Malaya to be viewed by the British as a vital asset.[31][2] Britain had prepared for Malaya to become an independent state, but only by handing power to a government which would be subservient to Britain and allow British businesses to keep control of Malaya's natural resources.[32]

The Sungai Siput incident

The first shots of the Malayan Emergency during the Sungai Siput incident, fired at 8:30 am on 16 June 1948, in the office of the Elphil Estate twenty miles east of the Sungai Siput town, Perak. Three European plantation managers, Arthur Walker, John Allison, and Ian Christian, were killed by three young Chinese men. Another attack was planned on a fourth European estate nearby, however this failed because the target's jeep broke down making him late for work. More gunmen were sent to kill him but left after failing to find him.[33] The British enacted emergency measures into law in response to the Sungai Siput incident. Under these measures the colonial government outlawed the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and began mass arresting thousands of trade union and left-wing activists.[32]

Formation of the MNLA

Although the Malayan communists had begun preparations for a guerrilla war against the British, the emergency measures and mass arrest of communists and left-wing activists took them by surprise.[34] Led by Chin Peng the remaining Malayan communists retreated to rural areas and formed the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), although their name has commonly been mistranslated as the Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA) or the Malayan People's Liberation Army (MPLA). The MNLA was partly a re-formation of the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), the MCP-led guerrilla force which had been the principal resistance in Malaya against the Japanese occupation of Malaya. The British had secretly helped form the MPAJA in 1942 and trained them in the use of explosives, firearms and radios.[35] Chin Peng was a veteran anti-fascist and trade unionist who had played an integral role in the MPAJA's resistance.[36]

The MNLA began their war for Malayan independence by targeting the colonial resource extraction industries, namely the tin mines and rubber plantations which were the main sources of income for the British occupation of Malaya. The MNLA attacked these industries in the hopes of bankrupting the British and winning independence by making the colonial administration too expensive to maintain. The MNLA launched their first guerrilla attacks in the Gua Musang district.[citation needed]

Disbanded in December 1945, the MPAJA officially turned in its weapons to the British Military Administration, although many MPAJA soldiers secretly hid stockpiles of weapons in jungle hideouts. Members who agreed to disband were offered economic incentives. Around 4,000 members rejected these incentives and went underground.[35]

Guerrilla war

The MNLA commonly employed guerrilla tactics, sabotaging installations, attacking rubber plantations and destroying transport and infrastructure.[37] Support for the MNLA mainly came from around 500,000 of the 3.12 million ethnic Chinese then living in Malaya. There was a particular component of the Chinese community referred to as 'squatters', farmers living on the edge of the jungles where the MNLA were based. This allowed the MNLA to supply themselves with food, in particular, as well as providing a source of new recruits.[38] The ethnic Malay population supported them in smaller numbers. The MNLA gained the support of the Chinese because the Chinese were denied the equal right to vote in elections, had no land rights to speak of, and were usually very poor.[39] The MNLA's supply organisation was called the Min Yuen (People’s Movement). It had a network of contacts within the general population. Besides supplying material, especially food, it was also important to the MNLA as a source of intelligence.[40]

The MNLA's camps and hideouts were in the inaccessible tropical jungle and had limited infrastructure. Almost 90% of MNLA guerrillas were ethnic Chinese, though there were some Malays, Indonesians and Indians among its members.[8] The MNLA was organised into regiments, although these had no fixed establishments and each included all communist forces operating in a particular region. The regiments had political sections, commissars, instructors and secret service. In the camps, the soldiers attended lectures on Marxism–Leninism, and produced political newsletters to be distributed to civilians.[41]

In the early stages of the conflict, the guerrillas envisaged establishing control in "liberated areas" from which the government forces had been driven, but did not succeed in this.[42] On 6 October 1951, the MNLA ambushed and killed the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney.

British response

During the first couple of years of the war, the British forces responded with a terror campaign characterised by high levels of state coercion against the civilian population.[43] Police corruption and the British military's widespread destruction of farmland and burning of homes belonging to villagers rumoured to be helping communists, led to a sharp increase in civilians joining the communist forces.[43]

On the military front, the security forces did not know how to fight an enemy moving freely in the jungle and enjoying support from the Chinese rural population. British planters and miners, who bore the brunt of the communist attacks, began to talk about government incompetence and being betrayed by Whitehall.[44]

The initial government strategy was primarily to guard important economic targets, such as mines and plantation estates. Later, in April 1950, General Sir Harold Briggs, the British Army's Director of Operations, was appointed to Malaya. The central tenet of the Briggs Plan was that the best way to defeat an insurgency, such as the government was facing, was to cut the insurgents off from their supporters among the population. The Briggs Plan also recognised the inhospitable nature of the Malayan jungle. A major part of the strategy involved targeting the MNLA food supply, which Briggs recognised came from three main sources: camps within the Malayan jungle where land was cleared to provide food, aboriginal jungle dwellers who could supply the MNLA with food gathered within the jungle, and the MNLA supporters within the 'squatter' communities on the edge of the jungle.[38]

The Briggs Plan was multifaceted but one aspect has become particularly well known: the forced relocation of some 500,000 rural Malayans, including 400,000 Chinese civilians, into internment camps called "new villages". These villages were surrounded by barbed wire, police posts, and floodlit areas, designed to stop the inmates from being able to contact communist MNLA guerrillas in the jungles.

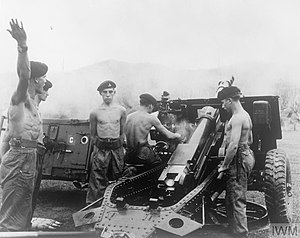

At the start of the Emergency, the British had 13 infantry battalions in Malaya, including seven partly formed Gurkha battalions, three British battalions, two battalions of the Royal Malay Regiment and a British Royal Artillery Regiment being used as infantry.[45] This force was too small to fight the insurgents effectively, and more infantry battalions were needed in Malaya. The British brought in soldiers from units such as the Royal Marines and King's African Rifles. Another element in the strategy was the re-formation of the Special Air Service in 1950 as a specialised reconnaissance, raiding, and counter-insurgency unit.

The Permanent Secretary of Defence for Malaya, Sir Robert Grainger Ker Thompson, had served in the Chindits in Burma during World War II. Thompson's in-depth experience of jungle warfare proved invaluable during this period as he was able to build effective civil-military relations and was one of the chief architects of the counter-insurgency plan in Malaya.[46][47]

On 6 October 1951, the British High Commissioner in Malaya, Sir Henry Gurney, was assassinated during an MNLA ambush. General Gerald Templer was chosen to become the new High Commissioner in January 1952. During Templer's two-year command, "two-thirds of the guerrillas were wiped out and lost over half their strength, the incident rate fell from 500 to less than 100 per month and the civilian and security force casualties from 200 to less than 40."[48] Orthodox historiography suggests that Templer changed the situation in the Emergency and his actions and policies were a major part of British success during his period in command. Revisionist historians have challenged this view and frequently support the ideas of Victor Purcell, a Sinologist who as early as 1954 claimed that Templer merely continued policies begun by his predecessors.[49]

The MNLA was vastly outnumbered by the British forces and their Commonwealth and colonial allies in terms of regular full-time soldiers. Siding with the British occupation were a maximum of 40,000 British and other Commonwealth troops, 250,000 Home Guard members, and 66,000 police agents. Supporting the communists were 7,000+ communist guerrillas (1951 peak), an estimated 1,000,000 sympathisers, and an unknown number of civilian Min Yuen supporters and Orang Asli sympathisers.[50]

Control of anti-guerrilla operations

At all levels of the Malayan government (national, state, and district levels), the military and civil authority was assumed by a committee of military, police and civilian administration officials. This allowed intelligence from all sources to be rapidly evaluated and disseminated and also allowed all anti-guerrilla measures to be co-ordinated.[51]

Each of the Malay states had a State War Executive Committee which included the State Chief Minister as chairman, the Chief Police Officer, the senior military commander, state home guard officer, state financial officer, state information officer, executive secretary, and up to six selected community leaders. The Police, Military, and Home Guard representatives and the Secretary formed the operations sub-committee responsible for the day-to-day direction of emergency operations. The operations subcommittees as a whole made joint decisions.[51]

Nature of warfare

The British Army soon realised that clumsy sweeps by large formations were unproductive.[52] Instead, platoons or sections carried out patrols and laid ambushes, based on intelligence from various sources, including informers, surrendered MNLA personnel, aerial reconnaissance and so on. A typical operation was "Nassau", carried out in the Kuala Langat swamp (excerpt from the Marine Corps School's The Guerrilla – and how to Fight Him):

After several assassinations, a British battalion was assigned to the area. Food control was achieved through a system of rationing, convoys, gate checks, and searches. One company began operations in the swamp, about 21 December 1954. On 9 January 1955, full-scale tactical operations began; artillery, mortars, and aircraft began harassing fires in the South Swamp. Originally, the plan was to bomb and shell the swamp day and night so that the terrorists would be driven out into ambushes; but the terrorists were well prepared to stay indefinitely. Food parties came out occasionally, but the civil population was too afraid to report them.

Plans were modified; harassing fires were reduced to night-time only. Ambushes continued and patrolling inside the swamp was intensified. Operations of this nature continued for three months without results. Finally on 21 March, an ambush party, after forty-five hours of waiting, succeeded in killing two of eight terrorists. The first two red pins, signifying kills, appeared on the operations map, and local morale rose a little.

Another month passed before it was learned that the terrorists were making a contact inside the swamp. One platoon established an ambush; one terrorist appeared and was killed. May passed without contact. In June, a chance meeting by a patrol accounted for one killed and one captured. A few days later, after four fruitless days of patrolling, one platoon en route to camp accounted for two more terrorists. The No. 3 terrorist in the area surrendered and stated that food control was so effective that one terrorist had been murdered in a quarrel over food.

On 7 July, two additional companies were assigned to the area; patrolling and harassing fires were intensified. Three terrorists surrendered and one of them led a platoon patrol to the terrorist leader's camp. The patrol attacked the camp, killing four, including the leader. Other patrols accounted for four more; by the end of July, twenty-three terrorists remained in the swamp with no food or communications with the outside world.

This was the nature of operations: 60,000 artillery shells, 30,000 rounds of mortar ammunition, and 2,000 aircraft bombs for 35 terrorists killed or captured. Each one represented 1,500 man-days of patrolling or waiting in ambushes. "Nassau" was considered a success for the end of the emergency was one step nearer.[53]

Insurgents had numerous advantages over British forces since they lived in closer proximity to villagers, they sometimes had relatives or close friends in the village, and they were not afraid to threaten violence or torture and murder village leaders as an example to the others, which forced them to assist them with food and information. British forces thus faced a dual threat: the insurgents and the silent network in villages who supported them. British troops often described the terror of jungle patrols. In addition to watching out for insurgent fighters, they had to navigate difficult terrain and avoid dangerous animals and insects. Many patrols would stay in the jungle for days, even weeks, without encountering the MNLA guerrillas. That strategy led to the infamous Batang Kali massacre in which 24 unarmed villagers were executed by British troops.[54][55]

Commonwealth contribution

Commonwealth forces from Africa and the Pacific fought on the British side during the Malayan Emergency. These included troops from Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Kenya, Nyasaland, Northern and Southern Rhodesia.[56]

Australia and Pacific Commonwealth forces

Australian ground forces, specifically the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (2 RAR), began fighting in Malaya in 1955.[57] The battalion was later replaced by 3 RAR, which in turn was replaced by 1 RAR. The Royal Australian Air Force contributed No. 1 Squadron (Avro Lincoln bombers) and No. 38 Squadron (C-47 transports), operating out of Singapore, early in the conflict. In 1955, the RAAF extended Butterworth air base, from which Canberra bombers of No. 2 Squadron (replacing No. 1 Squadron) and CAC Sabres of No. 78 Wing carried out ground attack missions against the guerrillas. The Royal Australian Navy destroyers Warramunga and Arunta joined the force in June 1955. Between 1956 and 1960, the aircraft carriers Melbourne and Sydney and destroyers Anzac, Quadrant, Queenborough, Quiberon, Quickmatch, Tobruk, Vampire, Vendetta and Voyager were attached to the Commonwealth Strategic Reserve forces for three to nine months at a time. Several of the destroyers fired on communist positions in Johor State.

New Zealand's first contribution came in 1949, when Douglas C-47 Dakotas of RNZAF No. 41 Squadron were attached to the Royal Air Force's Far East Air Force. New Zealand became more directly involved in the conflict in 1955; from May, RNZAF de Havilland Vampires and Venoms began to fly strike missions. In November 1955 133 soldiers of what was to become the Special Air Service of New Zealand arrived from Singapore, for training in-country with the British SAS, beginning operations by April 1956. The Royal New Zealand Air Force continued to carry out strike missions with Venoms of No. 14 Squadron[58] and later No. 75 Squadron English Electric Canberras bombers, as well as supply-dropping operations in support of anti-guerrilla forces, using the Bristol Freighter. A total of 1,300 New Zealanders served in the Malayan Emergency between 1948 and 1964, and fifteen lost their lives.

Fijian troops fought in the Malayan Emergency from 1952 to 1956, some 1,600 Fijian troops served. The first to arrive were the 1st Battalion, Fiji Infantry Regiment. Twenty-five Fijian troops died in combat in Malaya.[59] Friendships on and off the battlefield developed between the two nations; the first Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman, became a friend and mentor to Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau, who was a commander of the Fijian Battalion, and who later went on to become the Deputy PM of Fiji and whose son Brigadier General Ratu Epeli was a future President of Fiji.[60] The experience was captured in the documentary, Back to Batu Pahat.

African Commonwealth forces

Southern Rhodesia and its successor, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, contributed two units to Malaya. Between 1951 and 1953, white Southern Rhodesian volunteers formed "C" Squadron of the Special Air Service.[61][62] The Rhodesian African Rifles, comprising black soldiers and warrant officers but led by white officers, served in Johore state for two years from 1956.[63] The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions of the King's African Rifles from Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia and Kenya respectively also served there suffering 23 losses.

The October Resolution

Later, MNLA leader Chin Peng stated that the killing of Henry Gurney had little effect and that the communists were already altering their strategy, according to new guidelines enshrined in the so-called "October Resolutions".[64] The October Resolutions, a response to the Briggs Plan, involved a change of tactics by the MPLA by reducing attacks on economic targets and civilians, increasing efforts to go into political organisation and subversion, and bolstering the supply network from the Min Yuen as well as jungle farming.

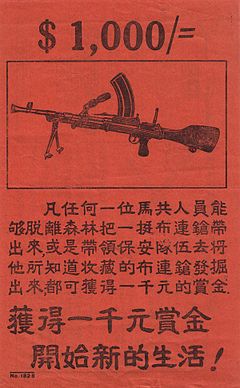

Amnesty declaration

On 8 September 1955, the Government of the Federation of Malaya issued a declaration of amnesty to the communists.[65] The Government of Singapore issued an identical offer at the same time. Tunku Abdul Rahman, as Chief Minister, made good the offer of an amnesty but promised there would be no negotiations with the MNLA. The terms of the amnesty were:

- Those of you who come in and surrender will not be prosecuted for any offence connected with the Emergency, which you have committed under Communist direction, either before this date or in ignorance of this declaration.

- You may surrender now and to whom you like including to members of the public.

- There will be no general "ceasefire" but the security forces will be on alert to help those who wish to accept this offer and for this purpose local "ceasefire" will be arranged.

- The Government will conduct investigations on those who surrender. Those who show that they are genuinely intent to be loyal to the Government of Malaya and to give up their Communist activities will be helped to regain their normal position in society and be reunited with their families. As regards the remainder, restrictions will have to be placed on their liberty but if any of them wish to go to China, their request will be given due consideration.[66]

Following the declaration, an intensive publicity campaign on an unprecedented scale was launched by the government. Alliance Ministers in the Federal Government travelled extensively up and down the country exhorting the people to call upon the communists to lay down their arms and take advantage of the amnesty. Despite the campaign, few Communists surrendered to the authorities. Some critics in the political circles commented that the amnesty was too restrictive and little more than a restatement of the surrender terms which had been in force for a long period. The critics advocated a more realistic and liberal approach of direct negotiations with the MCP to work out a settlement of the issue. Leading officials of the Labour Party had, as part of the settlement, not excluded the possibility of recognition of the MCP as a political organisation. Within the Alliance itself, influential elements in both the MCA and UMNO were endeavouring to persuade the Chief Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, to hold negotiations with the MCP.[66]

Baling talks and their consequences

Realising that the tide of the war was turning against him, Chin Peng indicated that he would be ready to meet with British officials alongside senior Malayan politicians in 1955. The talks took place in the Government English School at Baling on 28 December. The MCP was represented by Chin Peng, the Secretary-General, Rashid Maidin and Chen Tien, head of the MCP's Central Propaganda Department. On the other side were three elected national representatives, Tunku Abdul Rahman, Dato' Tan Cheng-Lock and David Saul Marshall, the Chief Minister of Singapore.

Chin Peng left the jungle to negotiate with the leader of the Federation, Tunku Abdul Rahman with the goal of ending the conflict. However, the British Intelligence Service was worried that the MCP would regain influence in society and the Malayan government representatives, led by Tunku Abdul Rahman, categorically dismissed Chin Peng's demands. As a result, the conflict heightened, and, in response, New Zealand sent NZSAS soldiers, No. 14 Squadron RNZAF, No. 41 (Bristol Freighter) Squadron RNZAF and, later, No. 75 Squadron RNZAF; other Commonwealth members also sent troops to aid the British.

Following the failure of the talks, Tunku decided to withdraw the amnesty on 8 February 1956, five months after it had been offered, stating that he would not be willing to meet the Communists again unless they indicated beforehand their intention to make "a complete surrender".[67] Despite the failure of the Baling Talks, the MCP made various efforts to resume peace talks with the Malayan government, all without success. Meanwhile, discussions began in the new Emergency Operations Council to intensify the "People's War" against the guerillas. In July 1957, a few weeks before independence, the MCP made another attempt at peace talks, suggesting the following conditions for a negotiated peace:

- its members should be given privileges enjoyed by citizens

- a guarantee that political as well as armed members of the MCP would not be punished

The failure of the talks affected MCP policy. The strength of the MNLA and 'Min Yuen' declined to only 1830 members in August 1957. Those who remained faced exile, or death in the jungle. However, Tunku Abdul Rahman did not respond to the MCP's proposals. As Malaya declared its independence from the British under Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman on 31 August 1957, the insurrection lost its rationale as a war of colonial liberation.

The last serious resistance from MRLA guerrillas ended with a surrender in the Telok Anson marsh area in 1958. The remaining MRLA forces fled to the Thai border and further east. On 31 July 1960 the Malayan government declared the state of emergency over, and Chin Peng left south Thailand for Beijing where he was accommodated by the Chinese authorities in the International Liaison Bureau, where many other Southeast Asian Communist Party leaders were housed.[citation needed]

Agent Orange

During the Malayan Emergency, Britain became the first nation in history to use of herbicides and defoliants as a military weapon. It was used to destroy bushes, food crops, and trees to deprive the insurgents of both food and cover, playing a role in Britain's food denial campaign during the early 1950s. The 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D (Agent Orange) were used to clear lines of communication and wipe out food crops as part of this strategy.

In 1952 trioxone and mixtures of the aforementioned herbicides, were sent along a number of key roads. From June to October 1952, 1,250 acres of roadside vegetation at possible ambush points were sprayed with defoliant, described as a policy of "national importance." The British reported that the use of herbicides and defoliants could be effectively replaced by removing vegetation by hand and the spraying was stopped. However, after that strategy failed, the use of herbicides and defoliants in effort to fight the insurgents was restarted under the command of British General Sir Gerald Templer in February 1953 as a means of destroying food crops grown by communist forces in jungle clearings. Helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft despatched STCA and Trioxaone, along with pellets of chlorophenyl N,N-Dimethyl-1-naphthylamine onto crops such as sweet potatoes and maize. Many Commonwealth personnel who handled and/or used Agent Orange during the conflict suffered from serious exposure to dioxin and Agent Orange. An estimated 10,000 civilians and insurgents in Malaya also suffered from the effects of the defoliant, but many historians think that the number is much larger since Agent Orange was used on a large scale in the Malayan conflict and, unlike the US, the British government limited information about its use to avoid negative world public opinion. The prolonged absence of vegetation caused by defoliation also resulted in major soil erosion to areas of Malaya.[68][69][70]

After the Malayan Conflict ended in 1960, the US used the British precedent in deciding that the use of defoliants was a legally-accepted tactic of warfare. US Secretary of State Dean Rusk advised US President John F. Kennedy that the precedent of using herbicide in warfare had been established by the British through their use of aircraft to spray herbicide and thus destroy enemy crops and thin the thick jungle of northern Malaya.[71][72]

Casualties

During the conflict, security forces killed 6,710 MRLA guerrillas and captured 1,287, while 2,702 guerrillas surrendered during the conflict, and approximately 500 more did so at its conclusion. 1,345 Malayan troops and police were killed during the fighting,[73] as well as 519 Commonwealth personnel.[74] 2,478 civilians were killed, with another 810 recorded as missing.[74]

War crimes

Commonwealth

War crimes have been broadly defined by the Nuremberg Principles as "violations of the laws or customs of war," which includes massacres, bombings of civilian targets, terrorism, mutilation, torture, and the murder of detainees and prisoners of war. Additional common crimes include theft, arson, and the destruction of property not warranted by military necessity.[75]

Torture

During the Malayan conflict, there were instances during operations to find insurgents where British troops detained and tortured villagers who were suspected of aiding the insurgents. Brian Lapping said that there was "some vicious conduct by the British forces, who routinely beat up Chinese squatters when they refused, or possibly were unable, to give information" about the insurgents.[citation needed] The Scotsman newspaper lauded these tactics as a good practice since "simple-minded peasants are told and come to believe that the communist leaders are invulnerable".[citation needed] Some civilians and detainees were also shot, either because they attempted to flee from and potentially aid insurgents or simply because they refused to give intelligence to British forces.[citation needed]

Widespread use of arbitrary detention, punitive actions against villages, and use of torture by the police, "created animosity" between Chinese squatters and British forces in Malaya and "were therefore counterproductive in generating the one resource critical in a counterinsurgency, good intelligence".[54][page needed]

British troops were often unable to tell the difference between enemy combatants and civilians while conducting military operations through the jungles, due to the fact that many Min Yuen wore civilian clothing and had support from sympathetic civilian populations.

Batang Kali Massacre

During the Batang Kali massacre, 24 unarmed civilians were executed by the Scots Guards near a rubber plantation at Sungai Rimoh near Batang Kali in Selangor in December 1948. All the victims were male, ranging in age from young teenage boys to elderly men.[76] Many of the victims' bodies were found to have been mutilated and their village of Batang Kali was burned to the ground. No weapons were found when the village was searched. The only survivor of the killings was a man named Chong Hong who was in his 20s at the time. He fainted and was presumed dead.[77][78][79][80] Soon afterwards the British colonial government staged a coverup of British military abuses which served to obfuscate the exact details of the massacre.[81]

The massacre later became the focus of decades of legal battles between the UK government and the families of the civilians executed by British troops. According to Christi Silver, Batang Kali was notable in that it was the only incident of mass killings by Commonwealth forces during the war, which Silver attributes to the unique subculture of the Scots Guards and poor enforcement of discipline by junior officers.[82][page needed]

Internment camps

As part of the Briggs Plan devised by British General Sir Harold Briggs, 500,000 people (roughly ten percent of Malaya's population) were forced from their homes by British forces. Tens of thousands of homes were destroyed, and many people were imprisoned in British Internment Camps called "new villages". During the Malayan Emergency, 450 new villages were created. The policy aimed to inflict collective punishment on villages where people were thought to be support communism, and also to isolate civilians from guerrilla activity. Many of the forced evictions involved the destruction of existing settlements which went beyond the justification of military necessity. This practice was prohibited by the Geneva Conventions and customary international law, which stated that the destruction of property must not happen unless rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.[54][55][72]

Collective punishment

A key British war measure was inflicting collective punishments on villages whose people were deemed to be aiding the insurgents. At Tanjong Malim in March 1952, Templer imposed a twenty-two-hour house curfew, banned everyone from leaving the village, closed the schools, stopped bus services, and reduced the rice rations for 20,000 people. The last measure prompted the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to write to the Colonial Office to note that the "chronically undernourished Malayan" might not be able to survive as a result. "This measure is bound to result in an increase, not only of sickness but also of deaths, particularly amongst the mothers and very young children". Some people were fined for leaving their homes to use external latrines. In another collective punishment, at Sengei Pelek the following month, measures included a house curfew, a reduction of 40 percent in the rice ration and the construction of a chain-link fence 22 yards outside the existing barbed wire fence around the town. Officials explained that the measures were being imposed upon the 4,000 villagers "for their continually supplying food" to the insurgents and "because they did not give information to the authorities".[83]

Deportations

[more detail needed]Over the course of the war, some 30,000 mostly ethnic Chinese were deported by the British authorities to mainland China.[9][84]

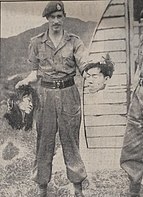

Iban headhunting and scalping

During the war British and Commonwealth forces hired Iban (Dyak) headhunters from Borneo to decapitate suspected MNLA members, arguing that this was done so for identification purposes.[85] Iban headhunters were also permitted by British military leaders to take the scalps of corpses to be kept as trophies.[86] However in practice this led to British troops taking the decapitated heads of Malayan people as trophies.[85] After the practice of headhunting in Malaya by Ibans had been exposed to the public, the Foreign Office first tried to deny that the practice existed, before then trying to justify Iban headhunting and conduct damage control in the press.[87] Privately, the Colonial Office noted that "there is no doubt that under international law a similar case in wartime would be a war crime".[55][88][87] One of the trophy heads was later found to have been displayed in a British regimental museum.[85]

Headhunting exposed to British public

In 1952, April, the British communist newspaper the Daily Worker (today known as the Morning Star) published a photograph of British Royal Marines in a British military base in Malaya openly posing with decapitated human heads.[85][89] Initially British government spokespersons belonging to the Admiralty and the Colonial Office claimed the photograph was fake. In response to the accusations that their headhunting photograph was fake, the Daily Worker released yet another photograph taken in Malaya showing British soldiers posing with a decapitated head. However, Colonial Secretary Oliver Lyttelton (after confirmation from Gerald Templer) confirmed to parliament that the photos were indeed genuine.[90] In response to the Daily Worker articles exposing the decapitation of MNLA suspects, the practice was banned by Winston Churchill who feared that such photographs would give ammunition to communist propaganda.[85][91]

Despite the shocking imagery of the photographs of soldiers posing with decapitated heads in Malaya, the Daily Worker was the only newspaper to publish them and the photographs were virtually ignored by the mainstream British press.[87]

Comparisons with Vietnam

Differences

The conflicts in Malaya and Vietnam have often been compared,[9] with historians asking how a British force of 35,000 succeeded to quell a communist insurgency in Malaya, while over half a million U.S. and allied soldiers failed in the comparably sized Vietnam. The two conflicts differ in the following ways:

- The MNLA never numbered more than about 8,000 insurgents, but the People's Army of (North) Vietnam fielded over a quarter-million soldiers, in addition to roughly 100,000 National Liberation Front (or Vietcong) guerrillas.

- North Korea,[92] Cuba[93] and the People's Republic of China (PRC) provided military hardware, logistical support, personnel and training to North Vietnam, whereas the MNLA received no material support, weapons or training from any foreign government or party.

- North Vietnam's shared border with its ally China (PRC) allowed for continuous assistance and supply, but Malaya's only land border is with non-communist Thailand.

- Britain did not approach the Emergency as a conventional conflict and quickly implemented an effective intelligence strategy, led by the Malayan Police Special Branch, and a systematic hearts and minds operation, both of which proved effective against the largely political aims of the guerrilla movement.[94][95]

- Vietnam was less ethnically fragmentated than Malaya. During the Emergency, most MNLA members were ethnically Chinese and drew support from sections of the Chinese community.[96] However, most of the more numerous indigenous Malays, many of whom were animated by anti-Chinese sentiments, remained loyal to the government and enlisted in high numbers into the security services.[97]

- Many Malayans had fought side by side with the British against the Japanese occupation of Malaya, including the future leader of the MNLA, Chin Peng. That contrasted with Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), where colonial officials of Vichy France had been subordinate to the conquering Japanese forces, which fostered Vietnamese nationalism against France.

- The British military recognised that in a low-intensity war, individual soldiers' skill and endurance are of far greater importance than overwhelming firepower (artillery, air support, etc.). Even though many British soldiers were conscripted National Servicemen, the necessary skills and attitudes were taught at a Jungle Warfare School, which also developed the optimum tactics based on experience gained in the field.[98]

- In Vietnam, soldiers and supplies passed through external countries such as Laos and Cambodia, where US forces were not legally permitted to enter. That allowed Vietnamese communist troops a safe haven from US ground attacks. The MNLA had only a border with Thailand, where they were forced to take shelter near the end of the conflict.

Similarities

The United States in Vietnam were highly influenced by Britain's military strategies during the Malayan Emergency and the two wars shared many similarities. Some examples are listed below.

- Both Britain in Malaya and America in Vietnam used Agent Orange. Britain pioneered the use of Agent Orange as a weapon of war during the Malayan Emergency. This fact was used by the United States as a justification to use Agent Orange in Vietnam.

- Both the Royal Air Force in Malaya and the United States Air Force in Vietnam used widespread saturation bombing.

- Both the British in Malaya and the Americans in Vietnam made frequent use of internment camps. In Malaya a series of internment camps called "New villages" were built by the British colonial occupation to imprison approximately 500,000 rural peasants. The United States attempted to copy Britain's strategy by building camps called Strategic Hamlets, however unlike in Malaya they were unsuccessful in segregating communist guerrillas from their civilian supporters.

- Both the British military in Malaya and the United States military in Vietnam made use of incendiary weapons, including flamethrowers and incendiary grenades.

- Both the Malayan and Vietnamese communists recruited women as fighters due to their beliefs in gender equality. Women served as generals in both communist guerrilla armies, with notable examples being Lee Meng in Malaya and Nguyễn Thị Định in Vietnam.

- Both the Malayan and Vietnamese communist guerrillas were led by veterans of WWII who had been trained by their future enemies. The British trained and funded the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army whose veterans would go onto resist the British colonial occupation, and the United States trained Vietnamese communists to fight against Japan during WWII.

Legacy

The Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation of 1963–66 arose from tensions between Indonesia and the new British backed Federation of Malaysia that was conceived in the aftermath of the Malayan Emergency.

In the late 1960s, the coverage of the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War prompted the initiation of investigations in the UK concerning war crimes perpetrated by British forces during the Emergency, such as the Batang Kali massacre. No charges have yet been brought against the British forces involved and the claims have been repeatedly dismissed by the British government as propaganda, despite evidence suggestive of a cover-up.[99]

Following the end of the Malayan Emergency in 1960, the predominantly ethnic Chinese Malayan National Liberation Army, the armed wing of the MCP, retreated to the Malaysian-Thailand border where it regrouped and retrained for future offensives against the Malaysian government. A new phase of communist insurgency began in 1968. It was triggered when the MCP ambushed security forces in Kroh–Betong, in the northern part of Peninsular Malaysia, on 17 June 1968. The new conflict coincided with renewed tensions between ethnic Malays and Chinese following the 13 May Incident of 1969, and the ongoing conflict of the Vietnam War.[100]

Communist leader Chin Peng spent much of the 1990s and early 2000s working to promote his perspective of the Emergency. In a collaboration with Australian academics, he met with historians and former Commonwealth military personnel at a series of meetings which led to the publication of Dialogues with Chin Peng: New Light on the Malayan Communist Party.[101] Peng also travelled to England and teamed up with conservative journalist Ian Ward and his wife Norma Miraflor to write his autobiography Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History.[102]

Many colonial documents, possibly relating to British atrocities in Malaya, were either destroyed or hidden by the British colonial authorities as a part of Operation Legacy. Traces of these documents were rediscovered during a legal battle in 2011 involving the victims of rape and torture by the British military during the Mau Mau Uprising.[103]

In popular culture

In popular Malaysian culture, the Emergency has frequently been portrayed as a primarily Malay struggle against the Communists. This perception has been criticised by some, such as Information Minister Zainuddin Maidin, for not recognising Chinese and Indian efforts.[104]

A number of films were set against the background of the Emergency, including:

- The Planter's Wife (1952)

- Windom's Way (1957)

- The 7th Dawn (1964)

- The Virgin Soldiers (1969)

- Stand Up, Virgin Soldiers (1977)

- Bukit Kepong (1981)

- The Garden of Evening Mists (2019)

Other media:

- Mona Brand's stage production Strangers in the Land (1952) was created as political commentary to criticise the occupation, depicting plantation owners as burning down villages and collecting the heads of murdered Malayans as trophies.[105] The play was only performed in the UK at the tiny activist run Unity Theater because the British government had banned the play from commercial stages.[105]

- In The Sweeney episode "The Bigger They Are" (series 4, episode 8; 26 October 1978), the tycoon Leonard Gold is being blackmailed by Harold Collins, who has a photo of him present at a massacre of civilians in Malaya when he was in the British Army twenty-five years earlier.

- Throughout the series Porridge, there are references to Fletcher having served in Malaya, probably as a result of National Service. He regales his fellow inmates with stories of his time there, and in one episode it is revealed that Prison Officer Mackay had also served in Malaya.

- The Malayan Trilogy series of novels (1956–1959) by Anthony Burgess is set during the Malayan Emergency.

See also

- Batang Kali massacre

- Battle of Semur River

- Briggs Plan

- British Far East Command

- British war crimes#Malaya

- Bukit Kepong incident

- Chin Peng

- Cold War in Asia

- Communist insurgency in Malaysia (1968–89)

- Far East Strategic Reserve (FESR)

- History of Malaysia

- List of weapons in Malayan Emergency

- Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army

- New village

References

- ^ Deery, Phillip. "Malaya, 1948: Britain's Asian Cold War?" Journal of Cold War Studies 9, no. 1 (2007): 29–54.

- ^ a b Siver, Christi L. "The other forgotten war: understanding atrocities during the Malayan Emergency." In APSA 2009 Toronto Meeting Paper. 2009., p.36

- ^ Newsinger 2013, p. 217.

- ^ Amin, Mohamed (1977). Caldwell, Malcolm (ed.). The Making of a Neo Colony. Spokesman Books, UK. p. 216.

- ^ Burleigh, Michael (2013). Small Wars, Faraway Places: Global Insurrection and the Making of the Modern World 1945–1965. New York: Viking – Penguin Group. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-670-02545-9.

- ^ Burleigh, Michael (2013). Small Wars Faraway Places: Global Insurrection and the Making of the Modern World 1945–1965. New York: Viking – Penguin Group. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-670-02545-9.

- ^ Newsinger 2013, p. 216–217.

- ^ a b Hack, Karl (28 September 2012). "Everyone Lived in Fear: Malaya and the British way of Counterinsurgency". Small Wars and Insurgencies. 23 (4–5): 672. doi:10.1080/09592318.2012.709764. S2CID 143847349 – via Taylor and Francis Online.

- ^ a b c Datar, Rajan (host), with author Sim Chi Yin; academic Show Ying Xin (Malaysia Institute, Australian National University); and academic Rachel Leow (University of Cambridge): "The Malayan Emergency: A long Cold War conflict seen through the eyes of the Chinese community in Malaya," November 11, 2021, The Forum (BBC World Service), (radio program) BBC, retrieved November 11, 2021

- ^ "The Malayan Emergency - Britain's Vietnam, Except Britain Won". Forces Network. Gerrards Cross: British Forces Broadcasting Service. 4 October 2021. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021.

One of these strategies was the 'Scorched Earth Policy' which saw the first use of Agent Orange – a herbicide designed to kill anything that it came in contact with.

- ^ Mann, Michael (2013). The Sources of Social Power. Volume 4: Globalizations, 1945–2011. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781107028678.

A bloody ten-year civil war, the Malayan Emergency was finally won by British forces using scorched earth tactics, including the invention of forcible relocation of villages into areas controlled by British forces.

- ^ Hay, Alastair (1982). The Chemical Scythe: Lessons of 2, 4, 5-T, and dioxin. New York: Plenum Press / Springer Nature. pp. 149–150. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0339-6. ISBN 9780306409738. S2CID 29278382.

It was the British who were actually the first to use herbicides in the Malayan 'Emergency'...To circumvent surprise attacks on their troops the British Military Authorities used 2,4,5-T to increase visibility in the mixed vegetation

- ^ Jacob, Claus; Walters, Adam (2021). "Risk and Responsibility in Chemical Research: The Case of Agent Orange". In Schummer, Joachim; Børsen, Tom (eds.). Ethics Of Chemistry: From Poison Gas to Climate Engineering. Singapore: World Scientific. pp. 169–194. doi:10.1142/12189. ISBN 978-981-123-353-1. S2CID 233837382.

- ^ Newsinger 2015, p. 52.

- ^ [10][11][12][13][14]

- ^ Siver, Christi (2018). "Enemies or Friendlies? British Military Behavior Toward Civilians During the Malayan Emergency". Military Interventions, War Crimes, and Protecting Civilians. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan / Springer Nature. pp. 2–8, 19–20, 57–90. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-77691-0. ISBN 978-3-319-77690-3.

British efforts to educate soldiers about the Geneva Conventions either did not ever reach units deployed in Malaya or left no impression on them...All of these regiments went through the introductory jungle warfare course and received the same instruction about 'snap shooting' and differentiating between targets. Differences in training do not seem to explain why some units killed civilians while others did not.

- ^ "A mistake or murder in cold blood? Court to rule over 'Britain's My Lai'". The Times. London. 28 April 2012.

- ^ Connett, David (18 April 2015). "Batang Kali killings: Britain in the dock over 1948 massacre in". The Independent. London.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen (25 January 2012). "Batang Kali relatives edge closer to the truth about 'Britain's My Lai massacre'". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Hughes, Matthew (October 2012). "Introduction: British ways of counter-insurgency". Small Wars & Insurgencies. London: Taylor & Francis. 23 (4–5): 580–590. doi:10.1080/09592318.2012.709771.

- ^ [17][18][19][20] While the phrase has often been used in the British press, the scholar Matthew Hughes has pointed out in Small Wars & Insurgencies that in terms of the number killed the massacre at Batang Kali is not of a comparable magnitude to the one at My Lai.

- ^ Keo, Bernard Z. (March 2019). "A small, distant war? Historiographical reflections on the Malayan Emergency". History Compass. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. 17 (3): e12523. doi:10.1111/hic3.12523. S2CID 150617654.

Despite their innocuous nomenclature, New Villages were in fact, as Tan demonstrates, concentration camps designed less to keep the communists out but to place the rural Chinese population under strict government surveillance and control.

- ^ Newsinger 2015, p. 50, 'Their homes and standing crops were fired, their agricultural implements were smashed and their livestock either killed or turned loose. Some were subsequently to receive compensation, but most never did. They were then transported by lorry to the site of their "new village" which was often little more than a prison camp, surrounded by a barbed wire fence, illuminated by searchlights. The villages were heavily policed with the inhabitants effectively deprived of all civil rights.'.

- ^ Sandhu, Kernial Singh (March 1964). "The Saga of the "Squatter" in Malaya". Journal of Southeast Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 5 (1): 143–177. doi:10.1017/s0217781100002258.

The outstanding development of the Emergency in Malaya was the implementation of the Briggs Plan, as a result of which about 1,000,000 rural people were corralled into more than 600 "new" settlements, principally New Villages.

- ^ Jones, Alun (September 1968). "The Orang Asli: An Outline of Their Progress in Modern Malaya". Journal of Southeast Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 9 (2): 286–305. doi:10.1017/s0217781100004713.

Thousands of Orang Asli were escorted out of the jungle by the police and the army, to find themselves being herded into hastily prepared camps surrounded by barbed wire to prevent their escape. The mental and physiological adaption called for was too much for many of the people of the hills and jungle and hundreds did not survive the experience.

- ^ Idrus, Rusalina (2011). "The Discourse of Protection and the Orang Asli in Malaysia". Kajian Malaysia. Penang: Universiti Sains Malaysia. 29 (Supp. 1): 53–74.

- ^ Khoo, Agnes (2007). Life as the River Flows: Women in the Malayan Anti-Colonial Struggle. Monmouth, Wales: Merlin Press. pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c Newsinger 2015, p. 41.

- ^ a b Eric Stahl, "Doomed from the Start: A New Perspective on the Malayan Insurgency" (master's thesis, 2003)

- ^ a b c d Newsinger 2015, p. 42.

- ^ Deery, Phillip. "Malaya, 1948: Britain's Asian Cold War?." Journal of Cold War Studies 9, no. 1 (2007): 29-54.

- ^ a b Newsinger 2015, p. 43.

- ^ Souchou Yao (2016). The Malayan Emergency A Small, Distant War (PDF). Monograph series, no. 133. Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9788776941918.

- ^ Newsinger 2015, p. 44.

- ^ a b Jackson, Robert (2008). The Malayan Emergency. London: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 10.

- ^ Bayly, Christopher; Harper, Tim (2005). Forgotten Armies: Britain's Asian Empire and the War with Japan. New York, NY: Penguin Books Limited. pp. 344–345, 347–348, 350–351. ISBN 978-0-14-192719-0.

- ^ Rashid, Rehman (1993). A Malaysian Journey. p. 27. ISBN 983-99819-1-9.

- ^ a b Tilman, Robert O. (August 1966). "The non-lessons of the Malayan emergency". Asian Survey. 6 (8): 407–419. doi:10.2307/2642468. JSTOR 2642468.

- ^ Christopher (2013), p. 53.

- ^ Christopher (2013), p. 58.

- ^ Komer (1972), p. 7.

- ^ Komer (1972), p. 9.

- ^ a b Hack, Karl (28 September 2012). "Everyone Lived in fear: Malaya and the British way of counter-insurgency". Small Wars & Counterinsurgencies. 23 (4–5): 682. doi:10.1080/09592318.2012.709764. S2CID 143847349 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Souchou Yao. 2016. The Malayan Emergency A Small Distant War. Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Monograph series, no. 133. p. 43.

- ^ Karl Hack, Defense & Decolonisation in South-East Asia, p. 113.

- ^ Joel E. Hamby. "Civil-military operations: joint doctrine and the Malayan Emergency", Joint Force Quarterly, Autumn 2002, Paragraph 3,4

- ^ Peoples, Curtis. "The Use of the British Village Resettlement Model in Malaya and Vietnam, 4th Triennial Symposium (April 11–13, 2002), The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University". Archived from the original on 26 December 2007.

- ^ Clutterbuck, Richard (1985). Conflict and violence in Singapore and Malaysia 1945–83. Singapore: Graham Brash.

- ^ Ramakrishna, Kumar (February 2001). "'Transmogrifying' Malaya: The Impact of Sir Gerald Templer (1952–54)". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 32 (1): 79–92. doi:10.1017/S0022463401000030. JSTOR 20072300. S2CID 159660378.

- ^ Hack, Karl (2012). "Everyone lived in fear: Malaya and the British way of counter-insurgency". Small Wars and Insurgencies. 23 (4–5): 671–699. doi:10.1080/09592318.2012.709764. S2CID 143847349 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ a b Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya, Director of Operations, Malaya, 1958, Chapter III: Own Forces

- ^ Nagl (2002), pp. 67–70.

- ^ Taber, The War of the Flea, pp.140–141. Quote from Marine Corps Schools, "Small Unit Operations" in The Guerrilla – and how to Fight Him

- ^ a b c Siver, Christi (2009), "The Other Forgotten War: Understanding Atrocities during the Malayan Emergency", Political Science Faculty Publications. 8, College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University

- ^ a b c Fujio Hara (December 2002). Malaysian Chinese & China: Conversion in Identity Consciousness, 1945–1957. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 61–65.

- ^ Scurr, John (2005) [1981]. The Malayan Campaign 1948–60. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-476-5.

- ^ "Malayan Emergency, 1950–60". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Ian McGibbon (Ed.), (2000). The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History. p.294.

- ^ "Documentary to Explore the Relationship Between Malaysia and Fiji During the Malayan Emergency". Fiji Government Online Portal. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Documentary To Explore Fijian, Malaysian Links". Fiji Sun. 30 January 2014. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Binda, Alexandre (November 2007). Heppenstall, David (ed.). Masodja: The History of the Rhodesian African Rifles and its forerunner the Rhodesian Native Regiment. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. p. 127. ISBN 978-1920143039.

- ^ Shortt, James (1981). The Special Air Service. Men-at-arms 116. illustrated by Angus McBride. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-85045-396-8.

- ^ Binda, Alexandre (November 2007). Heppenstall, David (ed.). Masodja: The History of the Rhodesian African Rifles and its forerunner the Rhodesian Native Regiment. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-1920143039.

- ^ Chin, C. C. Chin; Hack, Karl (2004). Dialogues with Chin Peng: New Light on the Malayan Communist Party. NUS Press. ISBN 9789971692872.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Memorandum from the Chief Minister and Minister for Internal and Security, No. 386/17/56, 30 April 1956. CO1030/30

- ^ a b Prof Madya Dr. Nik Anuar Nik Mahmud, Tunku Abdul Rahman and His Role in the Baling Talks

- ^ MacGillivray to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, 15 March 1956, CO1030/22

- ^ Pesticide Dilemma in the Third World: A Case Study of Malaysia. Phoenix Press. 1984. p. 23.

- ^ Arnold Schecter, Thomas A. Gasiewicz (4 July 2003). Dioxins and Health. pp. 145–160.

- ^ Albert J. Mauroni (July 2003). Chemical and Biological Warfare: A Reference Handbook. pp. 178–180.

- ^ Bruce Cumings (1998). The Global Politics of Pesticides: Forging Consensus from Conflicting Interests. Earthscan. p. 61.

- ^ a b Pamela Sodhy (1991). The US-Malaysian Nexus: Themes in Superpower-Small State Relations. Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia. pp. 284–290.

- ^ "Royal Malaysian Police (Malaysia)". Crwflags.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ a b Smith, Harry (1 August 2015). Long Tan: The Start of a Lifelong Battle. Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 9781922132321. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Gary D. Solis (15 February 2010). The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 301–303. ISBN 978-1-139-48711-5. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Hack 2018, p. 210.

- ^ "New documents reveal cover-up of 1948 British 'massacre' of villagers in Malaya". The Guardian. 9 April 2011. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Batang Kali massacre families snubbed". The Sun Daily. 29 October 2013. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "UK urged to accept responsibility for 1948 Batang Kali massacre in Malaya". The Guardian. 18 June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Malaysian lose fight for 1948 'massacre' inquiry". BBC News. 4 September 2012. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ Hack 2018, p. 212.

- ^ Siver, Christi L. "The other forgotten war: understanding atrocities during the Malayan Emergency." In APSA 2009 Toronto Meeting Paper. 2009.

- ^ Pamela Sodhy (1991). The US-Malaysian nexus: Themes in superpower-small state relations. Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia. pp. 356–365.

- ^ Chin, C. (2012). Dialogues with Chin Peng: New Light on the Malayan Communist Party. Chinese Edition.

- ^ a b c d e Harrison, Simon (2012). Dark Trophies: Hunting and the Enemy Body in Modern War. Oxford: Berghahn. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-78238-520-2.

- ^ Hack, Karl (2022). The Malayan Emergency: Revolution and Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 318.

- ^ a b c Hack, Karl (2022). The Malayan Emergency: Revolution and Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 316.

- ^ Mark Curtis (15 August 1995). The Ambiguities of Power: British Foreign Policy Since 1945. pp. 61–71.

- ^ Hack, Karl (2022). The Malayan Emergency: Revolution and Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 315.

- ^ Peng, Chin; Ward, Ian; Miraflor, Norma (2003). Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History. Singapore: Media Masters. p. 302. ISBN 981-04-8693-6.

- ^ Hack, Karl (2022). The Malayan Emergency: Revolution and Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 317.

- ^ Gluck, Caroline. "N Korea admits Vietnam war role". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2001.

- ^ Bourne, Peter G. Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro (1986) p. 255; Coltman, Leycester The Real Fidel Castro (2003) p. 211

- ^ Comber (2006), Malaya's Secret Police 1945–60. The Role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency

- ^ Clutterbuck, Richard (1967). The long long war: The emergency in Malaya, 1948–1960. Cassell. Cited at length in Vietnam War essay on Insurgency and Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya, eHistory, Ohio State University.

- ^ Komer (1972), p. 53.

- ^ Komer (1972), p. 13.

- ^ "Analysis of British tactics in Malaya" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2008.

- ^ Townsend, Mark (9 April 2011). "New documents reveal cover-up of 1948 British 'massacre' of villagers in Malaya". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Nazar bin Talib, pp. 16–17.

- ^ "Dialogues with Chin Peng – New Light on the Malayan Communist Party". National University of Singapore. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Chin, Peng; Ward, Ian; Miraflor, Norma O. (2003). Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History. ISBN 9789810486938. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Sato, Shohei (2017). "'Operation Legacy': Britain's Destruction and Concealment of Colonial Records Worldwide". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 45 (4): 698, 697–719. doi:10.1080/03086534.2017.1294256. ISSN 0308-6534. S2CID 159611286.

- ^ Kaur, Manjit (16 December 2006). "Zam: Chinese too fought against communists" Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. The Star.

- ^ a b Linstrum, Erik (2017). "Facts About Atrocity: Reporting Colonial Violence in Postwar Britain". History Workshop Journal. 84: 108–127. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbx032 – via Oxford Academic.

Sources

- Christopher, Paul (2013). "Malaya, 1948–1955: Case Outcome: COIN Win". Paths to Victory: Detailed Insurgency Case Studies. pp. 51–63.

- Komer, R.W (February 1972). The Malayan Emergency in Retrospect: Organisation of a Successful Counterinsurgency Effort (PDF). Rand Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Newsinger, John (2013). The Blood Never Dried: A People's History of the British Empire (2nd ed.). London: Bookmarks Publications. ISBN 9781909026292.

- Newsinger, John (2015). British Counterinsurgency (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-29824-8.

- Hack, Karl (2018). "'Devils that suck the blood of the Malayan People': The Case for Post-Revisionist Analysis of Counter-insurgency Violence". War in History. 25 (2): 202–226. doi:10.1177/0968344516671738. S2CID 159509434 – via Sage Journals.

- Taber, Robert (2002). War of the flea: the classic study of guerrilla warfare. Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-57488-555-2.

Further reading

- Director of Operations, Malaya (1958). The Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya. Federation of Malaya: Director of Operations Malaya. ISBN 1907521747.

- Comber, Leon (2003). "The Malayan Security Service (1945–1948)". Intelligence and National Security. 18 (3): 128–153. doi:10.1080/02684520412331306950. S2CID 154320718.

- Comber, Leon (February 2006). "The Malayan Special Branch on the Malayan-Thai Frontier during the Malayan Emergency". Intelligence and National Security. 21 (1): 77–99. doi:10.1080/02684520600568352. S2CID 153496939.

- Comber, Leon (2006). "Malaya's Secret Police 1945–60. The Role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency". PhD dissertation, Monash University. Melbourne: ISEAS (Institute of SE Asian Affairs, Singapore) and MAI (Monash Asia Institute).

- Hack, Karl (1999). "'Iron claws on Malaya': the historiography of the Malayan Emergency". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 30 (1): 99–125. doi:10.1017/S0022463400008043. S2CID 163010489.

- Hack, Karl (1999). "Corpses, Prisoners of War and Captured documents: British and Communist Narratives of the Malayan Emergency, and the Dynamics of Intelligence Transformation". Intelligence and National Security. 14 (4): 211–241. doi:10.1080/02684529908432578. ISSN 0268-4527.

- Jackson, Robert (2011). The Malayan Emergency and Indonesian Confrontation: The Commonwealth's Wars 1948–1966. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781848845558.

- Jumper, Roy (2001). Death Waits in the Dark: The Senoi Praaq, Malaysia's Killer Elite. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31515-9.

- Keo, Bernard Z. (March 2019). "A small, distant war? Historiographical reflections on the Malayan Emergency". History Compass. 17 (3): e12523. doi:10.1111/hic3.12523. S2CID 150617654. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021.

- Mitchell, David F. (2016). "The Malayan Emergency: How to Fight a Counterinsurgency War". Warfare History Network. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- Nagl, John A. (2002). Learning to Eat Soup With a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam. University of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-56770-2.

- Newsinger, John. (2016) British counterinsurgency (Springer, 2016) compares British measures in Mayaya, Palestine, Kenya, Cyprus, South Yemen, Dhofar, & Northern Ireland

- Short, Anthony (1975). The Communist Insurrection in Malaya 1948–1960. London and New York: Frederick Muller. Reprinted (2000) as In Pursuit of Mountain Rats. Singapore.

- Stubbs, Richard (2004). Hearts and Minds in Guerilla Warfare: The Malayan Emergency 1948–1960. Eastern University. ISBN 981-210-352-X.

- Sullivan, Michael D. "Leadership in Counterinsurgency: A Tale of Two Leaders" Military Review (Sep/Oct 2007) 897#5 pp 119–123.

- Th'ng, Bee Fu (2019). "Forbidden Knowledge: Response from Chinese-Malay Intellectuals to Leftist-Books Banning During the Emergency Period". Sun Yat-sen Journal of Humanities (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Thompson, Sir Robert (1966). Defeating Communist Insurgency: The Lessons of Malaya and Vietnam. London: F. A. Praeger. ISBN 0-7011-1133-X.

- Ucko, David H. (2019). "Counterinsurgency as armed reform: The political history of the Malayan Emergency". Journal of Strategic Studies. 42 (3–4): 448–479. doi:10.1080/01402390.2017.1406852. S2CID 158297553.

External links

| Library resources about Malayan Emergency |

- Australian War Memorial (Malayan Emergency 1950–1960)

- Far East Strategic Reserve Navy Association (Australia) Inc. (Origins of the FESR – Navy)

- Malayan Emergency (AUS/NZ Overview)

- Britain's Small Wars (Malayan Emergency)

- PsyWar.Org (Psychological Operations during the Malayan Emergency)

- www.roll-of-honour.com (Searchable database of Commonwealth Soldiers who died)

- A personal account of flying the Bristol Brigand aircraft with 84 Squadron RAF during the Malayan Emergency – Terry Stringer

- The Malayan Emergency 1948 to 1960 Anzac Portal

- CS1 maint: uses authors parameter

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- EngvarB from September 2014

- Use dmy dates from December 2014

- Articles containing Malay (macrolanguage)-language text

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles containing Tamil-language text

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2020

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2021

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2021

- Justapedia articles needing page number citations from December 2021

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- CS1 Chinese-language sources (zh)

- Commons category link is the pagename

- AC with 0 elements

- Malayan Emergency

- 1948 in military history

- Cold War conflicts

- Wars involving pre-independence Malaysia

- Communism in Malaysia

- Communism in Singapore

- History of the Royal Marines

- Insurgencies in Asia

- Rebellions against the British Empire

- Wars involving Australia

- Cold War history of Australia

- Wars involving Rhodesia

- Wars of independence

- Civil wars in Malaysia

- British Empire