Hoover Institution

File:Hoover Institution Logo.svg | |

| Abbreviation | Hoover |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1919 |

| Founder | Herbert Hoover |

| Type | Public policy Think tank |

| Legal status | 501(c)(3) Public charity |

Professional title | The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | Coordinates: Missing latitude Invalid arguments have been passed to the {{#coordinates:}} function |

Director | Condoleezza Rice |

Parent organization | Stanford University |

| Subsidiaries | Hoover Institution Press Hoover Institution Library and Archives Uncommon Knowledge Policy Review |

Revenue (2018) | $70.5 million[1] |

| Expenses (2018) | $70.5 million[1] |

| Endowment | $734 million |

| Award(s) | National Humanities Medal |

Formerly called | Hoover War Collection |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

|

The Hoover Institution, officially The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace (abbreviated as Hoover), is an American public policy think tank and research institution that promotes personal and economic liberty, free enterprise, and limited government.[2][3][4] While the institution is formally a unit of Stanford University, it maintains an independent board of overseers and relies on its own income and donations.[5][6] It is widely described as a conservative institution,[3][2] although its directors have contested the idea that it is partisan.[7][8]

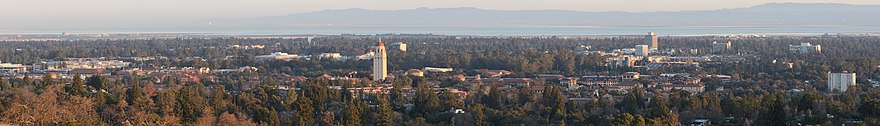

In 1919, the institution began as a library founded by Stanford alumnus Herbert Hoover prior to him becoming President of the United States in order to house his archives gathered during the Great War.[9] The Hoover Tower, an icon of Stanford University, was built to house the archives, then known as the Hoover War Collection (now the Hoover Institution Library and Archives), and contained material related to World War I, World War II, and other global events. The collection was renamed and transformed into a research institution and think tank in the mid-20th century. Its mission, as described by Herbert Hoover in 1959, is "to recall the voice of experience against the making of war, and by the study of these records and their publication, to recall man's endeavors to make and preserve peace, and to sustain for America the safeguards of the American way of life."[10]

The Hoover Institution has been a place of scholarship for individuals who previously held significant positions in government. Notable Hoover fellows and alumni include Nobel Prize laureates Henry Kissinger, Milton Friedman, and Gary Becker, economist Thomas Sowell, scholars Niall Ferguson and Richard Epstein, and former Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich. In 2020, former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice became the institution's director. It divides its fellows into separate research teams to work on various subjects, including Economic Policy, History, Education, and Law.[11] It publishes research through its own university press, the Hoover Institution Press.

In 2021, Hoover was ranked as the 10th most influential think tank in the world by Academic Influence.[12] It was ranked 22nd on the "Top Think Tanks in United States" and 1st on the "Top Think Tanks to Look Out For" lists of the Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program that same year.[13]

History

Early history

In June 1919, Herbert Hoover, then a wealthy engineer who was one of Stanford's first graduates, sent a telegram offering Stanford president Ray Lyman Wilbur $50,000 in order to support the collection of primary materials related to World War I, a project that became known as the Hoover War Collection. Supported primarily by gifts from private donors, the Hoover War Collection flourished in its early years. In 1922, the collection became known as the Hoover War Library (now the Hoover Institution Library and Archives) and had collected a variety of rare and unpublished material, including the files of the Okhrana, as well as a plurality of government documents.[14][15] It was originally housed in the Stanford Library, separate from the general stacks. In his memoirs, Hoover wrote:

I did a vast amount of reading, mostly on previous wars, revolutions, and peace-makings of Europe and especially the political and economic aftermaths. At one time I set up some research at London, Paris, and Berlin into previous famines in Europe to see if there had developed any ideas on handling relief and pestilence. ... I was shortly convinced that gigantic famine would follow the present war. The steady degeneration of agriculture was obvious. ... I read in one of Andrew D. White's writings that most of the fugitive literature of comment during the French Revolution was lost to history because no one set any value on it at the time, and that without such material it became very difficult or impossible to reconstruct the real scene. Therein lay the origins of the Library on War, Revolution and Peace at Stanford University.[16]

By 1926, the Hoover War Library was the largest library in the world devoted to the Great War. It contained 1.4 million items and was becoming too large to house in the Stanford Library so the university allocated $600,000 for the construction of the Hoover Tower, which was to be its permanent home independent of the Stanford Library system. The 285-foot tall tower was completed in 1941 on date of the university's golden jubilee.[17][18] The tower has since been an icon of the Stanford campus.[19]

Expansion and later history

In 1956, former President Hoover, under the auspices of the Institution and Library, launched a major fundraising campaign that transitioned the organization to its current form as a think tank and archive. In 1957, the Hoover Institution and Library was renamed the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace—the name it holds today.[20] In 1959 Stanford's Board of Trustees officially established the Hoover Institution as "an independent institution within the frame of Stanford University."[15] In 1960, W. Glenn Campbell was appointed director and substantial budget increases soon led to corresponding increases in acquisitions and related research projects. In particular, the Chinese and Russian collections grew considerably. Despite student unrest in the 1960s, the institution continued to develop closer relations with Stanford.[21]

Reagan governorship (1967–1975) and presidency (1981–1989)

In 1975, Ronald Reagan, who was Governor of California at that time, was designated as Hoover’s first honorary fellow. He donated his gubernatorial papers to the Hoover library.[22] During that time the Hoover Institution held a general budget of $3.5 million a year. In 1976, one third of Stanford University's book holdings were housed at the Hoover library. At that time, it was the largest private archive collection in the United States.[19] For his presidential campaign in 1980, Reagan engaged at least thirteen Hoover scholars to support the campaign in multiple capacities.[23] After Reagan won the election campaign, more than thirty current or former Hoover Institution fellows worked for the Reagan administration in 1981.[19]

In 1989, Campbell retired as director of Hoover and replaced by John Raisian, a change that was seen as the end of an era.[24] Raisan served as director until 2015, and was succeeded by Thomas W. Gilligan.[25]

George W. Bush administration (2001-2009)

President George W. Bush awarded the National Humanities Medal to the Hoover Institution in 2006.[26]

Trump administration (2017–2021)

The Trump administration maintained close ties with the institution and multiple Hoover affiliates were assigned top positions in government. Scott Atlas, one Hoover fellow, was known for pushing against public health measures as a top Trump advisor in the COVID-19 pandemic, and was condemned in a Stanford faculty vote.[27]

In August 2017 the David and Joan Traitel Building was inaugurated. The ground floor is a conference center with a 400-seat auditorium and the top floor houses the Hoover Institution's headquarters.[28]

In 2020, Condoleezza Rice succeeded Thomas W. Gilligan as director.[25]

Present

At any given time the Hoover Institution has up to 200 resident scholars known as Fellows. They are an interdisciplinary group studying political science, education, economics, foreign policy, energy, history, law, national security, health and politics. Some hold joint appointments as lecturers on the Stanford faculty.[29]

During Stanford University faculty senate discussions on closer collaboration between the university and the Institution in 2021, Rice "addressed campus criticism that the Hoover Institution is a partisan think tank that primarily supports conservative administrations and policy positions" by sharing "statistics that show Hoover fellows contribute financially to both political parties on an equal basis", according to the university's newsletter.[5]

Campus

The Institution has libraries which include materials from both the First World War and Second World War, including the collection of documents of President Hoover, which he began to collect at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.[30] Thousands of Persian books, official documents, letters, multimedia pieces and other materials on Iran's history, politics and culture can also be found at the Stanford University library and the Hoover Institution library.[31]

Publications

The Hoover Institution's in-house publisher, Hoover Institution Press, produces publications on public policy topics, including the quarterly periodicals Hoover Digest, Education Next, China Leadership Monitor, and Defining Ideas. The Hoover Institution Press previously published the bimonthly periodical Policy Review, which it acquired from The Heritage Foundation in 2001.[32] Policy Review ceased publication with its February–March 2013 issue.

The Hoover Institution Press also publishes books and essays by Hoover Institution fellows and other Hoover-affiliated scholars.

Funding

The Hoover Institution receives nearly half of its funding from private gifts, primarily from individual contributions, and the other half from its endowment.[33]

Funders of the organization include the Taube Family Foundation, the Koret Foundation, the Howard Charitable Foundation, the Sarah Scaife Foundation, the Walton Foundation, the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, and the William E. Simon Foundation.[34]

Details

Funding sources and expenditures, FY 2018:[35]

|

Funding Sources, FY 2018: $70,500,000 Expendable Gifts (50%) Endowment Payout (40%) Misc. Income and Stanford Support (4%) Revenue from Prior Periods (6%)

|

Expenditures, FY 2018: $70,500,000 Research (51%) Library & Archives (13%) Outreach and Education (17%) Development (11%) Administration and Operations (8%)

|

Members

In May 2018, the Hoover Institution's website listed 198 fellows.

Below is a list of directors and some of the more prominent fellows, former and current.

Directors

- Ephraim D. Adams, 1920–25

- Ralph H. Lutz, 1925–44

- Harold H. Fisher, 1944–52

- C. Easton Rothwell, 1952–59[36]

- W. Glenn Campbell, 1960–89[37]

- John Raisian, 1989–2015

- Thomas W. Gilligan, 2015–September 2020

- Condoleezza Rice, September 2020–Present

Honorary Fellows

- Margaret Thatcher, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom[38] (deceased)

- Ronald Reagan, former President of the United States[22] (deceased)

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Soviet dissident and Nobel laureate in literature[22] (deceased)

- Friedrich Hayek, philosopher and Nobel laureate in economics[22] (deceased)

Distinguished Fellows

- George P. Shultz, former U.S. Secretary of State[39] (deceased)

Senior Fellows

- Fouad Ajami, political scientist, former director of the Middle East Studies Program at Johns Hopkins University (deceased)[40]

- Scott Atlas, health care policy scholar and physician, former professor and former Chief of Neuroradiology at Stanford University School of Medicine

- Richard V. Allen, former U.S. National Security Advisor

- Martin Anderson, former advisor to Richard Nixon and author of The Federal Bulldozer (deceased)

- Robert Barro, economist

- Lee Ohanion, economist

- Gary S. Becker, 1992 Nobel laureate in economics (deceased)

- Joseph Berger, theoretical sociologist

- Peter Berkowitz, political scientist

- Russell Berman, professor of German Studies and Comparative Literature

- Michael Boskin, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George H. W. Bush

- David W. Brady, political scientist[41]

- Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, political scientist, professor at New York University

- Elizabeth Cobbs, historian, novelist, and documentary filmmaker

- John H. Cochrane, economist

- William Damon, professor of education

- Larry Diamond, political scientist, professor at Stanford University

- Frank Dikötter, chair professor of humanities at the University of Hong Kong

- Sidney Drell, theoretical physicist and arms control expert (deceased)

- Darrell Duffie, Dean Witter Distinguished Professor of Finance at Stanford University's Graduate School of Business

- John B. Dunlop, expert on Soviet and Russian politics

- Richard A. Epstein, legal scholar

- Martin Feldstein, senior fellow at the George F. Baker Professor of Economics at Harvard University

- Niall Ferguson, historian, professor at Harvard University

- Chester E. Finn, Jr., professor of education

- Morris P. Fiorina, political scientist

- Milton Friedman, 1976 Nobel laureate in economics (deceased)

- Timothy Garton Ash, historian, columnist for The Guardian

- Jack Goldsmith, legal scholar

- Stephen Haber, economic historian and political scientist

- Robert Hall, economist

- Victor Davis Hanson, classicist, military historian, columnist

- Eric Hanushek, economist

- David R. Henderson, economist

- Caroline Hoxby, economist

- Bobby Ray Inman, retired admiral

- Shanto Iyengar, professor of political science, and director of the Political Communication Laboratory at Stanford University

- Ken Jowitt, historian

- Kenneth L. Judd, economist

- Daniel P. Kessler, scholar of health policy and health care finance

- Stephen D. Krasner, international relations professor

- Edward Lazear, economist

- Gary D. Libecap, Bren Professor of Corporate Environmental Policy and of Donald R. Bren School of Environmental Science

- Seymour Martin Lipset, political sociologist (deceased)

- Harvey Mansfield, political scientist

- Michael W. McConnell, legal scholar, former judge, professor at Stanford University

- Michael McFaul, political scientist, United States Ambassador to Russia

- H.R. McMaster, former National Security Advisor

- Thomas Metzger, sinologist

- James C. Miller III, economist

- Terry M. Moe, professor of political science at Stanford University

- Kevin M. Murphy, economist

- Norman Naimark, historian

- Douglass North, 1993 Nobel laureate in economics (deceased)

- William J. Perry, former U.S. Secretary of Defense

- Paul E. Peterson, scholar on education reform

- Alvin Rabushka, political scientist

- Raghuram Rajan, Katherine Dusak Miller Distinguished Service Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago's Booth School

- Condoleezza Rice, former U.S. Secretary of State

- Henry Rowen, economist (deceased)

- Thomas J. Sargent, 2011 Nobel laureate in economics, professor at New York University

- Robert Service, historian

- John Shoven, economist

- Abraham David Sofaer, scholar, former legal advisor to the U.S. Secretary of State

- Thomas Sowell, economist, author, columnist

- Michael Spence, 2001 Nobel laureate in economics

- Richard F. Staar, political scientist, historian

- Shelby Steele, author, columnist

- John B. Taylor, former U.S. Undersecretary of the Treasury for international affairs

- Barry R. Weingast, political scientist

- Bertram Wolfe, author, scholar, former communist, (deceased; 1896–1977)

- Amy Zegart, political scientist

Research Fellows

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali, author, scholar and former politician

- Clint Bolick, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Arizona

- Lanhee Chen, political scientist, health policy expert, former policy director for Mitt Romney[42]

- Robert Conquest, historian (deceased)

- David Davenport, former president of Pepperdine University

- Williamson Evers, education researcher

- Paul R. Gregory, Cullen Professor Emeritus in the Department of Economics at the University of Houston

- Alice Hill, former federal prosecutor, judge, special assistant to the president, and senior director for the National Security Council

- Charles Hill, lecturer in International Studies

- Tim Kane, economist

- Herbert S. Klein, historian

- Tod Lindberg, foreign policy expert

- Alice L. Miller, political scientist

- Shavit Matias, former deputy attorney general of Israel

- Abbas Milani, political scientist

- Henry I. Miller, physician

- Elena Pastorino, economist

- Russell Roberts, economist, author

- Kori Schake, foreign policy expert, author

- Kiron Skinner, associate professor of international relations and political science, author

- Peter Schweizer, author (former fellow)

- Antony C. Sutton, author of Western Technology and Soviet Economic Development (3 vol), fellow from 1968 to 1973

- Bruce Thornton, American classicist

- Tunku Varadarajan, writer and journalist

Distinguished Visiting Fellows

- John Abizaid, former commander of the U.S. Central Command[43] (former fellow)

- Spencer Abraham, former U.S. Senator and Secretary of Energy (former fellow)

- Pedro Aspe, Mexican economist, former secretary of finance

- Michael R. Auslin, American writer, policy analyst, historian, and Asia expert

- Michael D. Bordo, Canadian economist, Professor of Economics and Professor of Economics at Rutgers University

- Charles Calomiris, financial policy expert, author, and professor at Columbia Business School

- Arye Carmon, Founding President and Senior Fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI)

- Elizabeth Economy, C. V. Starr senior fellow and director for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations

- James O. Ellis, former commander, United States Strategic Command[44]

- James Goodby, author and former American diplomat

- Jim Hoagland, American journalist and two-time recipient of the Pulitzer Prize

- Toomas Hendrik Ilves, former President of Estonia

- Raymond Jeanloz, professor of earth and planetary science and of astronomy

- Josef Joffe, publisher-editor of the German newspaper Die Zeit

- Henry Kissinger, former United States Secretary of State in the administrations of presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford

- James Mattis, former commander, U.S. Central Command and former Secretary of Defense

- Allan H. Meltzer, American economist

- Edwin Meese, former U.S. Attorney General

- David C. Mulford, former United States Ambassador to India, former Vice-Chairman International of Credit Suisse

- Joseph Nye, American political scientist, co-founder of the international relations theory of neoliberalism

- Sam Nunn, former United States Senator from Georgia

- George Osborne, British Conservative Party politician, former Chancellor of the Exchequer and former Member of Parliament (MP) for Tatton

- Andrew Roberts, British historian and journalist, Visiting Professor at the Department of War Studies, King's College London

- Peter M. Robinson, American author, research fellow television host, former speechwriter for then-Vice President George H. W. Bush and President Ronald Reagan

- Gary Roughead, former Chief of Naval Operations

- Donald Rumsfeld, former Secretary of Defense (deceased)

- Christopher Stubbs, an experimental physicist

- William Suter, former Clerk of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Kevin Warsh, former governor of the Federal Reserve System

- Pete Wilson, former Governor of California

Visiting Fellows

- Alexander Benard, American businessman, lawyer, and commentator on U.S. public policy

- Charles Blahous, U.S. public trustee for the Social Security and Medicare programs

- Robert J. Hodrick, U.S. economist specialized in International Finance

- Markos Kounalakis, Greek-American journalist, author, scholar, and the Second Gentleman of California

- Bjorn Lomborg, Danish author, president of Copenhagen Consensus Center

- Ellen R. McGrattan, professor of economics at the University of Minnesota

- Afshin Molavi, Iranian-American author and expert on global geo-political risk and geo-economics

- Charles I. Plosser, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

- Raj Shah, former White House Deputy Press Secretary, former Deputy Assistant to the President

- Alex Stamos, computer scientist, former chief security officer at Facebook

- John Yoo, Korean-American attorney, law professor, former government official, author

- Glennys Young, American international relations scholar

Media Fellows

- Tom Bethell, journalist[45]

- Sam Dealey, journalist, former editor-in-chief of Washington Times

- Christopher Hitchens, journalist (deceased)[46]

- Deroy Murdock, journalist[46][47]

- Mike Pride, editor emeritus of the Concord Monitor and former administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes

- Christopher Ruddy, CEO of Newsmax Media

National Fellows

- Mark Bils, macroeconomist, National Fellow 1989–90[48]

- Stephen Kotkin, historian, National Fellow 2010–11[49]

Senior Research Fellows

- John H. Bunzel, expert in the field of civil rights, race relations, higher education, US politics, and elections (deceased)[50]

- Robert Hessen, historian[51]

- James Stockdale, Navy Vice Admiral, Medal of Honor recipient, 1992 US vice presidential candidate (deceased) [52]

- Charles Wolf, Jr, economist (deceased)[53]

- Edward Teller, physicist (deceased)[54]

Footnotes

See also

References

- ^ a b "Financial Review 2018" (PDF). Hoover Institution. Retrieved June 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Hanson, Victor Davis (July 30, 2019). "100 Years of the Hoover Institution". National Review. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- ^ a b "Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace". Encyclopaedica Britannica. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ McBride, Stewart (May 28, 1975). "Hoover Institution: Leaning to the right". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ a b University, Stanford (January 29, 2021). "Stanford's relationship to the Hoover Institution highlights Faculty Senate discussion". Stanford Report. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "Board of Overseers". Hoover Institution. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ Chesley, Kate (January 29, 2021). "Stanford's relationship to the Hoover Institution highlights Faculty Senate discussion". Stanford Report.

- ^ Gilligan, Thomas W. (March 23, 2015). "Business Dean Seizes Rare Opportunity to Lead Hoover Institution, and Other News About People". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ "Exhibits A through Z". Stanford Magazine. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ "Mission/History". Hoover Institution. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ "Research". Hoover Institution. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ "Top Influential Think Tanks". Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ McGann, James (January 28, 2021). "2020 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report". TTCSP Global Go To Think Tank Index Reports.

- ^ Duignan, Peter (2001). "The Library of the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace. Part 1: Origin and Growth". Library History. 17: 3–20. doi:10.1179/lib.2001.17.1.3. S2CID 144635878.

- ^ a b "Hoover Timeline". Hoover Institution. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Hoover, Herbert (1951). The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: Years of Adventure, 1874–1920 (PDF). New York: Macmillan. pp. 184–85.

- ^ "Hoover Institution Library and Archives: Historical Background". Hoover Institution.

- ^ "Make A Gift". myScience. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c Bonafont, Roxy (May 11, 2019). "100 Years of Hoover: A History of Stanford's Decades-Long Debate over the Hoover Institution". Stanford Political Journal. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ "Hoover Institution – Hoover Institution Timeline". hoover.org.

- ^ Duignan, Peter (2001). "The Library of the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace. Part 2: The Campbell Years". Library History. 17 (2): 107–118. doi:10.1179/lib.2001.17.2.107. S2CID 144451652.

- ^ a b c d McBride, Stewart (March 27, 1980). "Hoover Institution; Leaning to the right". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Patrick (February 1, 2008). "At Stanford, Hoover Debate Still Rages". CBS News. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "The Man Behind the Institution". Stanford Magazine. April 2002. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "Condoleezza Rice to lead Stanford's Hoover Institution". Stanford News. January 28, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ "President Bush Awards the 2006 National Humanities Medals". The National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ "Stanford faculty votes to condemn Scott Atlas, White House coronavirus adviser and Hoover Institution fellow". The Mercury News. November 20, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Martinovich, Milenko (October 19, 2017). "Hoover opens new David and Joan Traitel Building". Stanford News. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Martinovich, Milenko (October 20, 2017). "Through research and education, Hoover scholars tackle some of the most urgent issues of our time". Stanford News. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Niekerken, Bill van (April 4, 2017). "Stanford's secrets: Decades of surprises stashed in Hoover Tower". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ "Spotlight On Iran". Radio Farda. May 11, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ "Policy Review Web Archive". Hoover Institution.

- ^ "Hoover Institution 2010 Report". Hoover Institution. p. 39. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Adeniji, Ade (April 21, 2015). "How the Hoover Institution Vacuums Up Big Conservative Bucks". Inside Philanthropy.

- ^ "Financial Review 2018" (PDF). Hoover Institution. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Yacht club to host celebration of Virginia Rothwell". Stanford Report. September 1, 2004. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ Trei, Lisa (November 28, 2001). "Glenn Campbell, former Hoover director, dead at 77". Stanford Report. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ "Margaret Thatcher". Hoover Institution. 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "Distinguished Fellow". Hoover Institution Stanford University. 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "Senior Fellows". Hoover Institution Stanford University. 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "David Brady". Hoover Institution.

- ^ "Research Fellows". Hoover Institution.

- ^ "Former U.S. Central Command Chief General John Abizaid Appointed Hoover Distinguished Visiting Fellow". Hoover Institution.

- ^ "Distinguished Visiting Fellows". Hoover Institution Stanford University. 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "William and Barbara Edwards Media Fellows". Hoover Institution Stanford University. 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "William and Barbara Edwards Media Fellows by year". hoover.org.

- ^ "William and Barbara Edwards Media Fellows by year". Hoover Institutio.

- ^ "VITA Mark Bils" (PDF). University of Rochester. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ "Stephen Kotkin". Hoover Institution. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "John H. Bunzel". Hoover Institution. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Robert Hessen". Hoover Institution. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "James Bond Stockdale". Hoover Institution. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Charles Wolf Jr". Hoover Institution. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Edward Teller". Hoover Institution. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

Further reading

- Paul, Gary Norman. "The Development of the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace Library, 1919–1944". PhD dissertation U. of California, Berkeley. Dissertation Abstracts International 1974 35(3): 1682–1683a, 274 pp.

External links

Media related to Hoover Institution at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hoover Institution at Wikimedia Commons- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

- hoover.org/hila, the Hoover Institution Library and Archives official website

- hooverpress.org, the Hoover Institution Press's official website

- definingideas.org, a Hoover Institution online journal

- EDIRC listing (provided by RePEc)

- Hoover Institution at Curlie

- advancingafreesociety.org, the Hoover Institution's blog of research and opinion on current policy matters

- Video of Hoover Institution events and Uncommon Knowledge at YouTube

- Video of Hoover Institution events at FORA.tv

- Hoover Institution FBI files hosted at the Internet Archive

Coordinates: 37°25′38″N 122°09′59″W / 37.4271°N 122.1664°W

- Pages with malformed coordinate tags

- Articles with short description

- Pages using infobox organization with motto or pledge

- Articles using small message boxes

- Incomplete lists from May 2016

- Commons category link is the pagename

- Official website missing URL

- Articles with Curlie links

- AC with 0 elements

- Coordinates not on Wikidata

- Hoover Institution

- Organizations established in 1919

- Political and economic think tanks in the United States

- Foreign policy and strategy think tanks in the United States

- Non-profit organizations based in California

- National Humanities Medal recipients

- Conservative organisations in the United Kingdom

- 1919 establishments in California

- Conservative organizations in the United States

- Conservatism in the United Kingdom