Ho Chi Minh City

Ho Chi Minh City

Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh Saigon (Sài Gòn) | |

|---|---|

| Saigon - Ho Chi Minh City | |

Clockwise from top: District 1 skyline, Independence Palace, Ben Thanh Market, Bach Dang Quay, Tomb of Lê Văn Duyệt, Municipal Theatre, City Hall, Saigon Notre-Dame Basilica | |

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto(s): | |

<mapframe>: The JSON content is not valid GeoJSON+simplestyle. The list below shows all attempts to interpret it according to the JSON Schema. Not all are errors.

Interactive map outlining Ho Chi Minh City | |

| Coordinates: 10°46′32″N 106°42′07″E / 10.77556°N 106.70194°ECoordinates: 10°46′32″N 106°42′07″E / 10.77556°N 106.70194°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Southeast |

| Founded | 1698 |

| Founded by | Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh |

| Named for | Ho Chi Minh |

| Districts | 16 urban districts, 5 rural districts and 1 sub-city |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Ho Chi Minh City People's Council |

| • Secretary of CPV | Nguyễn Văn Nên |

| • Chairwoman of People's Council | Nguyễn Thị Lệ |

| • Chairman of People's Committee | Phan Văn Mãi |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 2,061.2 km2 (795.83 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 30,595 km2 (11,813 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 19 m (63 ft) |

| Population (2023) | |

| • Municipality | 9,320,866 (1st) |

| • Density | 4,375/km2 (11,330/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 21,281,639 (1st) |

| • Metro density | 697.2/km2 (1,806/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Saigonese |

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (ICT) |

| Postal code | 700000–740000 |

| Area codes | 28 |

| ISO 3166 code | VN-SG |

| License plate | 41, 50–59 |

| GRP (Nominal) | 2022 |

| – Total | US$63.6 billion[4] |

| – Per capita | US$6,890 |

| GRP (PPP) | 2022 |

| – Total | US$199.7 billion[5] |

| – Per capita | US$21,640 |

| HDI (2020) | 0.795 (2nd)[6] |

| International airports | Tan Son Nhat International Airport (SGN) |

| Rapid transit system | Ho Chi Minh City Metro |

| Website | hochiminhcity |

Ho Chi Minh City (abbreviated HCMC),[a] also known as Saigon,[b] is the most populous city in Vietnam, with a population of around 9.3 million in 2023.[4] Situated in the Southeast region of Vietnam, the city surrounds the Saigon River and covers about 2,061 km2 (796 sq mi).

Saigon was the capital of French Indochina from 1887 to 1902, and again from 1945 until its cessation in 1954. Following the partition of French Indochina, it became the capital of South Vietnam until the fall of Saigon in 1975. The communist government renamed Saigon in honour of Hồ Chí Minh after the fall of Saigon. Beginning in the 1990s, the city underwent modernisation and expansion, contributing to Vietnam's post-war economic recovery.[7] It is known for French colonial architecture, street life,[8] its varied cultural institutions, which include historic landmarks, walking streets, museums and galleries which attracts over 8 million international visitors each year.[9][10]

Ho Chi Minh City is a centre for finance, media, technology, education, and transportation. The city generates around a quarter of the country's total GDP, and is home to multinational companies.[11] It has a Human Development Index of 0.795 (high), ranking second among all municipalities and provinces of Vietnam.[6] Tân Sơn Nhất International Airport, the main airport serving the city, is the busiest airport in the country by passenger traffic, accounting for nearly half of all international arrivals to Vietnam.[12]

Etymology

The first known human habitation of the area was a Cham settlement called Baigaur.[nb 1] The Cambodians then took over the Cham village of Baigaur and renamed it Prey Nokor, a small fishing village.[13][14] Over time, under the control of the Vietnamese, it was officially renamed Gia Định (嘉定), a name that was retained until the time of the French conquest in the 1860s, when it adopted the name Sài Gòn, westernized as Saïgon,[14] while the city was still indicated as 嘉定 on Vietnamese maps written in chữ Hán until at least 1891.[15]

The name Ho Chi Minh City was given after reunification in 1976 to honour Ho Chi Minh.[nb 2] The informal name of Sài Gòn remains in daily speech. There is a technical difference between the 2 terms: Sài Gòn is used to refer to the city centre in District 1 and the adjacent areas, while Ho Chi Minh City refers to all of its urban and rural districts.[14]

Saigon

柴棍 appears in Trịnh Hoài Đức's Gia Định thành thông chí (嘉定城通志 "Comprehensive Records about the Gia Định Citadel", c. 1820), Nam quốc địa dư giáo khoa thư (南國地輿教科書 "Textbook on the Geography of the Southern Country", 1908),[17] etc.

Adrien Launay's Histoire de la Mission de Cochinchine (1688−1823), "Documents Historiques II: 1728 - 1771" (1924: 190) cites 1747 documents containing the toponyms: provincia Rai-gon, Rai-gon thong (for *Sài Gòn thượng "Upper Saigon"), & Rai-gon-ha (for *Sài Gòn hạ "Lower Saigon").

It is probably a transcription of Khmer ព្រៃនគរ (Prey Nokôr)[18][19][nb 3], or Khmer ព្រៃគរ (Prey Kôr).

The proposal that Sài Gòn is from non-Sino-Vietnamese reading of Chinese 堤岸 tai4 ngon6 (“embankment”, SV: đê ngạn)[nb 4], the Cantonese name of Chợ Lớn, (e.g. by Vương Hồng Sển) has been critiqued as folk-etymological, as: (1) the Vietnamese source Phủ biên tạp lục (albeit written in literary Chinese) was the earliest extant one containing the local toponym's transcription; (2) 堤岸 has variant form 提岸, thus suggesting that both were transcriptions of a local toponym and thus are cognates to, not originals of, Sài Gòn. Saigon is unlikely to be from 堤岸 since in 南國地輿教科書 Nam Quốc địa dư giáo khoa thư, it also lists Chợ Lớn as 𢄂𢀲 separate from 柴棍 Sài Gòn.

Ho Chi Minh City

The official name, Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, was first proclaimed in 1945, and later adopted in 1976. It is abbreviated as TP.HCM, and translated in English as Ho Chi Minh City, abbreviated as HCMC, and in French as Hô-Chi-Minh-Ville (the circumflex is sometimes omitted), abbreviated as HCMV. The name commemorates Ho Chi Minh, the first leader of North Vietnam. This name, though not his given name, was one he favored throughout his later years. It combines a Vietnamese surname (Hồ, 胡) with a given name meaning "enlightened will" (from Sino-Vietnamese, 志 明; Chí meaning 'will' or 'spirit', and Minh meaning 'light'), in essence, meaning "light bringer".[22] "Sài Gòn" is used to refer to the city's central business districts, "Prey Nokor City" is known in Khmer, whereas "Hồ Chí Minh City" is used to refer to the whole city.[23]

History

Early settlement

The earliest settlement in the area was a Funan temple at the location of what later is the Phụng Sơn Buddhist temple, founded in the 4th century AD.[24] A settlement called Baigaur was established on the site in the 11th century by the Champa.[24] Baigaur was renamed Prey Nokor after conquest by the Khmer Empire around 1145,[24] Prey Nokor grew on the site of a fishing village and area of forest.[25]

The first Vietnamese people crossed the sea to explore this land completely without the organisation of the Nguyễn Lords. Thanks to the marriage between Princess Nguyễn Phúc Ngọc Vạn - daughter of Lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên - and the King of Cambodia Chey Chettha II in 1620, the relationship between Vietnam and Cambodia became "smooth", and the people of the 2 countries could freely move back and forth. In exchange, Chey Chettha II gifted Prei Nokor to the Nguyễn lords.[26]

Nguyễn Dynasty rule

In 1679, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Tần allowed a group of Chinese refugees from the Qing dynasty to settle in Mỹ Tho, Biên Hòa and Saigon to seek refuge. In 1698, Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh, a Vietnamese noble, was sent by the Nguyễn rulers of Huế by sea to establish Vietnamese administrative structures in the area, thus detaching the area from Cambodia, which was not strong enough to intervene. He is credited with the expansion of Saigon into a significant settlement.[27][28] King Chey Chettha IV of Cambodia tried to stop the Vietnamese and was defeated by Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh in 1700. In February 1700, he invaded Cambodia from An Giang. In March, the Vietnamese expedition under Cảnh and a Chinese general Trần Thượng Xuyên (Chen Shangchuan) defeated the main Cambodian army at Bích Đôi citadel, king Chey Chettha IV took flight while his nephew Ang Em surrendered to the invaders, as the Vietnamese marched onto and captured Cambodia's capital Phnom Penh.[29] As a result, Saigon and Long An were officially and securely obtained by the Nguyễn, more Vietnamese settlers moved into the new conquered lands.[29]

In 1788, Nguyễn Ánh captured the city, and used it as a centre of resistance against Tây Sơn.[30] 2 years later, a Vauban citadel called Gia Định, or Thành Bát Quái ("Eight Diagrams") was built by Victor Olivier de Puymanel, 1 of the Nguyễn Ánh's French mercenaries.[31]

The citadel was captured by Lê Văn Khôi during his revolt of 1833–35 against Emperor Minh Mạng. Following the revolt, Minh Mạng ordered it to be dismantled, and a new citadel, called Phụng Thành, was built in 1836.[32] In 1859, the citadel was destroyed by the French following the Battle of Kỳ Hòa.[32] Initially called Gia Định, the Vietnamese city became Saigon in the 18th century.[24]

French colonial era

Ceded to France by the 1862 Treaty of Saigon,[33] the city was planned by the French to transform into a town for colonisation. During the 19th and 20th centuries, construction of French-style buildings began, including a botanical garden, the Norodom Palace, Hotel Continental, Notre-Dame Cathedral, and Bến Thành Market, among others.[34][35] In April 1865, Gia Định Báo was established in Saigon, becoming the first newspaper published in Vietnam.[36] During the French colonial era, Saigon became known as "Pearl of the Orient" (Hòn ngọc Viễn Đông),[37] or "Paris of the Extreme Orient".[38]

On 27 April 1931, a new région called Saigon–Cholon consisting of Saigon and Cholon was formed; the name Cholon was dropped after South Vietnam gained independence from France in 1955.[39] From about 256,000 in 1930,[40] Saigon's population rose to 1.2 million in 1950.[40]

- Gallery of Saigon during the French colonial era

The Siege of Saigon in 1859 by Franco-Spanish forces.

French soldiers stationed at a barrack in Saigon in 1930.

Imperial Japanese soldiers entering in Saigon in 1941, during World War II.

Saigon afire after aerial attacks from carrier-based planes of the US Pacific Fleet in 1945.

Republic era

In 1949, former Emperor Bảo Đại made Saigon the capital of the State of Vietnam with himself as head of state.[7] In 1954, the Geneva Agreement partitioned Vietnam along the 17th parallel (Bến Hải River), with the communist Việt Minh, under Ho Chi Minh, gaining complete control of the northern half of the country, while the southern half gained independence from France.[41] The State officially became the Republic of Vietnam when Bảo Đại was deposed by his Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm in the 1955 referendum,[41] with Saigon as its capital.[42] On 22 October 1956, the city was given the official name, Đô Thành Sài Gòn ("Capital City Saigon").[43] After the decree of 27 March 1959 came into effect, Saigon was divided into 8 districts and 41 wards.[43] In December 1966, 2 wards from old An Khánh Commune of Gia Định, were formed into District 1, then seceded later to become District 9.[44] In July 1969, District 10 and District 11 were founded, and by 1975, the city's area consisted of 11 districts, Gia Định, Củ Chi District (Hậu Nghĩa), and Phú Hòa District (Bình Dương).[44]

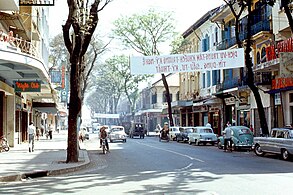

Saigon served as the financial, industrial and transport centre of the Republic of Vietnam.[45] In the 1950s, with the U.S. providing nearly $2 billion in aid to the Diệm regime, the country's economy grew under capitalism;[43] by 1960, over half of South Vietnam's factories were located in Saigon.[46] Beginning in the 1960s, Saigon experienced economic downturn and inflation, as it was completely dependent on U.S. aid and imports from other countries.[43] As a result of urbanisation, with the population reaching 3.3 million by 1970, the city was described by the USAID as being turned "into a huge slum".[47] The city underwent "prostitutes, drug addicts, corrupt officials, beggars, orphans, and Americans with money", and according to Stanley Karnow, it was "a black-market city in the largest sense of the word".[42]

On 28 April 1955, the Vietnamese National Army launched an attack against Bình Xuyên military force in the city. The battle lasted until May, killing an estimated 500 people and leaving about 20,000 homeless.[42][48] Ngô Đình Diệm then later turned on other paramilitary groups in Saigon, including the Hòa Hảo Buddhist reform movement.[42] On 11 June 1963, Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức burned himself in the city, in protest of the Diệm regime. On 1 November of the same year, Diệm was assassinated in Saigon, in a successful coup by Dương Văn Minh.[42]

During the 1968 Tet Offensive, communist forces launched a failed attempt to capture the city. On 30 April 1975, Saigon was captured, ending the Vietnam War with a victory for North Vietnam,[49] and the city came under the control of the Vietnamese People's Army.[42]

- Gallery of Saigon during the Republic of Vietnam era

The Independence Palace in 1967. It was the official residence and workplace of the President of South Vietnam.

The Saigon Opera House as seen from Tự Do (Liberty) Street in 1967.

Socialist Republic era

In 1976, upon the establishment of the unified communist Socialist Republic of Vietnam, the city of Saigon (including the Cholon area), the province of Gia Ðịnh and 2 suburban districts of 2 other nearby provinces were combined to create Ho Chi Minh City, in honour of the late Communist leader Ho Chi Minh.[nb 5] At the time, the city covered an area of 1,295.5 square kilometres (500.2 sq mi) with 8 districts and 5 rurals: Thủ Đức, Hóc Môn, Củ Chi, Bình Chánh, and Nhà Bè.[44] Since 1978, administrative divisions in the city have been revised times,[44] including in 2020, when District 2, District 9, and Thủ Đức District were consolidated to form a municipal city.[50]

On 29 October 2002, 60 people died and 90 injured in the International Trade Center building fire in Ho Chi Minh City.[51]

Ho Chi Minh City, along with its surrounding provinces, is described as "the manufacturing hub" of Vietnam, and "an attractive business hub".[52] In terms of cost, it was ranked the 111th-most expensive major city in the world according to a 2020 survey of 209 cities.[53] In terms of international connectedness, as of 2020, the city was classified as a "Beta" city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[54]

Geography

The city is located in the south-eastern region of Vietnam, 1,760 km (1,090 mi) south of Hanoi. The average elevation is 5 m (16 ft) above sea level for the city centre and 16 m (52 ft) for the suburb areas.[55] Due to its location on the Mekong Delta, the city is fringed by tidal flats that have been modified for agriculture.[56]

Climate

The city has a tropical climate, specifically tropical savanna (Aw), with a average humidity of 78–82%.[57] The year is divided into 2 seasons.[57] The rainy season, with an average rainfall of about 1,800 mm (71 in) annually (about 150 rainy days per year), lasts from May to November.[57] The dry season lasts from December to April.[57] The average temperature is 28 °C (82 °F), with variation throughout the year.[57] The highest temperature recorded was 40.0 °C (104 °F) in April while the lowest temperature recorded was 13.8 °C (57 °F) in January.[57] On average, the city experiences between 2,400 and 2,700 hours of sunshine per year.[57]

| Climate data for Ho Chi Minh City (Tan Son Nhat International Airport) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.4 (97.5) |

38.7 (101.7) |

39.4 (102.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

39.0 (102.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.9 (94.8) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

33.0 (91.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.3 (81.1) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.1 (82.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.4 (74.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 13.8 (56.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 12.0 (0.47) |

8.0 (0.31) |

18.0 (0.71) |

57.0 (2.24) |

202.0 (7.95) |

224.0 (8.82) |

231.0 (9.09) |

219.0 (8.62) |

490.0 (19.29) |

340.0 (13.39) |

128.0 (5.04) |

41.0 (1.61) |

1,970 (77.54) |

| Average rainy days | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 13.0 | 16.0 | 19.0 | 17.0 | 18.0 | 16.0 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 121 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 79 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 85 | 84 | 80 | 77 | 78 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 245 | 246 | 272 | 239 | 195 | 171 | 180 | 172 | 162 | 182 | 200 | 226 | 2,490 |

| Source 1: Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology,[58] Asian Development Bank[57] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (rainfall)[59] | |||||||||||||

Flooding

The city is considered 1 of the cities most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, particularly flooding. During the rainy season, a combination of tide, rains, flow volume in the Saigon River and Đồng Nai River and land subsidence results in regular flooding in parts of the city.[60][61] A once-in-100 year flood would cause 23% of the city to suffer flooding.[62]

Administration

The city is a municipality at the same level as Vietnam's provinces, which is subdivided into 22 district-level sub-divisions (as of 2020):

- 5 rural districts (1,601 km2 or 618 sq mi in area), which are designated as rural (huyện):

- 16 urban districts (283 km2 or 109 sq mi in area), which are designated urban or suburban (quận):

- 1 sub-city (211 km2 or 81 sq mi in area), which is designated municipal city (thành phố thuộc thành phố trực thuộc trung ương):

They are subdivided into 5 commune-level towns (or townlets), 58 communes, and 249 wards (as of 2020[update], see List of HCMC administrative units below).[63]

On 1 January 2021, it was announced that District 2, District 9 and Thủ Đức District would be consolidated and was approved by Standing Committee of the National Assembly.[64][50]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Area km2 | Population | Person/km2 | Urban | Rural | |||

| Census[65] | ||||||||

| 1999 | - | 5,034,058 | - | 4,207,825 | 826,233 | |||

| 2004 | - | 6,117,251 | - | 5,140,412 | 976,839 | |||

| 2009 | 2,097.1 | 7,162,864 | 3,416 | 5,880,615 | 1,282,249 | |||

| 2019 | 2,061.2 | 8,993,082 | 4,363 | 7,127,364 | 1,865,718 | |||

| Estimate | ||||||||

| 2010 | 2,095.6 | 7,346,600 | 3,506 | 6,114,300 | 1,232,300 | |||

| 2011 | 2,095.6 | 7,498,400 | 3,578 | 6,238,000 | 1,260,400 | |||

| 2012 | 2,095.6 | 7,660,300 | 3,655 | 6,309,100 | 1,351,100 | |||

| 2013 | 2,095.6 | 7,820,000 | 3,732 | 6,479,200 | 1,340,800 | |||

| 2014 | 2,095.5 | 7,981,900 | 3,809 | 6,554,700 | 1,427,200 | |||

| 2015 | 2,095.5 | 8,127,900 | 3,879 | 6,632,800 | 1,495,100 | |||

| 2016 | 2,061.4 | 8,287,000 | 4,020 | 6,733,100 | 1,553,900 | |||

| 2017 | 2,061.2 | 8,444,600 | 4,097 | 6,825,300 | 1,619,300 | |||

| Sources:[66][67][68][69] | ||||||||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 4,640,400 | — |

| 1996 | 4,747,900 | +2.3% |

| 1997 | 4,852,300 | +2.2% |

| 1998 | 4,957,300 | +2.2% |

| 1999 | 5,073,100 | +2.3% |

| 2000 | 5,274,900 | +4.0% |

| 2001 | 5,454,000 | +3.4% |

| 2002 | 5,619,400 | +3.0% |

| 2003 | 5,809,100 | +3.4% |

| 2004 | 6,007,600 | +3.4% |

| 2005 | 6,230,900 | +3.7% |

| 2006 | 6,483,100 | +4.0% |

| 2007 | 6,725,300 | +3.7% |

| 2008 | 6,946,100 | +3.3% |

| 2009 | 7,196,100 | +3.6% |

| 2010 | 7,378,000 | +2.5% |

| 2011 | 7,517,900 | +1.9% |

| 2012 | 7,663,800 | +1.9% |

| 2013 | 7,818,200 | +2.0% |

| 2014 | 8,244,400 | +5.5% |

| 2015 | 8,307,900 | +0.8% |

| 2016 | 8,441,902 | +1.6% |

| 2017 | 8,446,000 | +0.0% |

| 2018 | 8,843,200 | +4.7% |

| 2019 | 9,038,600 | +2.2% |

| 2020 | 9,227,600 | +2.1% |

| 2021 | 9,166,800 | −0.7% |

| Source: Tổng cục thống kê Việt Nam: 80 : 93 [70] | ||

The population of the city, as of the 1 October 2004 census, was 6,117,251 (of which 19 inner districts had 5,140,412 residents and 5 suburban districts had 976,839 inhabitants).[63] In 2007, the city's population was 6,650,942 – with the 19 inner districts home to 5,564,975 residents and the 5 suburban districts containing 1,085,967 inhabitants. The result of the 2009 Census shows that the city's population was 7,162,864 people,[71] about 8.34% of the total population of Vietnam, making it the highest population-concentrated city in the country. As of the end of 2012, the total population of the city was 7,750,900 people, an increase of 3.1% from 2011.[72] As an administrative unit, its population is the largest at the provincial level. According to the 2019 census, Ho Chi Minh City has a population of over 8.9 million within the city proper and over 21 million within its metropolitan area.[4]

The city's population is expected to grow to 13.9 million by 2025.[73] The population of the city is expanding faster than earlier predictions. In August 2017, the city's mayor, Nguyễn Thành Phong, admitted that previous estimates of 8–10 million were drastic underestimations.[74] The actual population (including those who have not officially registered) was estimated 13 million in 2017.[75] The Ho Chi Minh City Metropolitan Area, a metropolitan area covering most parts of the southeast region plus Tiền Giang Province and Long An Province under planning, will have an area of 30,000 km2 (12,000 sq mi) with a population of 20 million inhabitants by 2020.[76]

Ethnic groups

The majority of the population are ethnic Vietnamese (Kinh) at about 93.52%. Ho Chi Minh City's largest minority ethnic group are the Chinese (Hoa) with 5.78%. Cholon – in District 5 and parts of Districts 6, 10, and 11 – is home to the largest Chinese community in Vietnam. The Hoa (Chinese) speak a number of varieties of Chinese, including Cantonese, Teochew (Chaozhou), Hokkien, Hainanese, and Hakka; smaller numbers speak Mandarin Chinese. Other ethnic minorities include Khmer with 0.34%, Cham with 0.1%, and a group of Bawean from Bawean Island in Indonesia (about 400; as of 2015), they occupy District 1.[77]

Other nationalities including Koreans, Japanese, Americans, South Africans, Filipinos and Britons reside in Ho Chi Minh City, particularly in Thủ Đức and District 7 as expatriate workers.[78]

Religion

As of March 2019, the city recognises 13 religions and 1,983,048 residents identify as religious people. Catholicism and Buddhism are the 2 predominant religions in Saigon. The largest is Buddhism as it has 1,164,930 followers followed by Catholicism with 745,283 followers, Caodaism with 31,633 followers, Protestantism with 27,016 followers, Islam with 6,580 followers, Hòa Hảo with 4,894 followers, Tịnh độ cư sĩ Phật hội Việt Nam with 1,387 followers, Hinduism with 395 followers, Đạo Tứ ấn hiếu nghĩa with 298 followers, Minh Sư Đạo with 283 followers, Baháʼí Faith with 192 followers, Bửu Sơn Kỳ Hương with 89 followers, Minh Lý Đạo with 67 followers, and the rest are the Saigonese who don't believe in God which is Atheism.[79]

Economy

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Justapedia's quality standards. (December 2018) |

The city is the economic center of Vietnam and accounts for a proportion of the economy of Vietnam. While the city takes up 0.6% of the country's land area, it contains 8.34% of the population of Vietnam, 20.2% of its GDP, 27.9% of industrial output and 34.9% of the FDI projects in the country in 2005.[80] In 2005, the city had 4,344,000 labourers, of whom 130,000 are over the labour age norm (in Vietnam, 60 for male and 55 for female workers).[81] In 2009, GDP per capita reached $2,800, compared to the country's average level of $1,042.[82]

| Year | General description |

|---|---|

| 2006 | As of June 2006, the city has been home to 3 export processing zones and 12 industrial parks. Ho Chi Minh City is the leading recipient of foreign direct investment in Vietnam, with 2,530 FDI projects worth $16.6 billion at the end of 2007.[83] In 2007, the city received over 400 FDI projects worth $3 billion.[84] |

| 2007 | In 2007, the city's GDP was estimated at $14.3 billion, or about $2,180 per capita, up 12.6% from 2006 and accounting for 20% of the country's GDP. The GDP adjusted to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) reached $71.5 billion, or about $10,870 per capita (approximately 3 times higher than the country's average). The city's Industrial Product Value was $6.4 billion, equivalent to 30% of the value of the entire nation. Export – Import Turnover through HCMC ports accounted for $36 billion, or 40% of the national total, of which export revenue reached $18.3 billion (40% of Vietnam's total export revenues). In 2007, Ho Chi Minh City's contribution to the annual revenues in the national budget increased by 30%, accounting for about 20.5% of total revenues. The consumption demand of Ho Chi Minh City is higher than other Vietnamese provinces and municipalities and 1.5 times higher than that of Hanoi.[85][failed verification] |

| 2008 | In 2008, it attracted $8.5 billion in FDI.[86] In 2010, the city's GDP was estimated at $20.902 billion, or about $2,800 per capita, up 11.8% from 2009.[87] |

| 2012 | By the end of 2012, the city's GDP was estimated around $28,595 billion[dubious ], or about $3,700 per capita, up 9.2% from 2011.[88] Total trade (export and import) reached $47.7 billion, with export at $21.57 billion and import $26.14 billion.[72] |

| 2013 | In 2013, GDP of the city grew 7.6% by Q1, 8.1% by Q2, and 10.3% by the end of Q3. By the end of 2013, the city's GDP grew 9.3%, with GDP per capita reaching $4,500.[89] |

| 2014 | By the end of 2014, the city's GDP grew 9.5%, with GDP per capita reaching $5,100.[90] |

| 2020 | The city's economic performance transcended 6%, at 7.84% from 2016-2019 and 2016-2020; the town grew at 6,59%. Its performance assists the city in reaching the GDP per capita at $6.328;[91] it yielded the preferred growth at $9.800 per capita due to the repercussion result of Covid-19.[92] |

Sectors

The economy of the city consists of industries ranging from mining, seafood processing, agriculture, and construction, to tourism, finance, industry and trade. The state-owned sector makes up 33.3% of the economy, the private sector 4.6%, and the remainder in foreign investment. Concerning its economic structure, the service sector accounts for 51.1%, industry and construction account for 47.7% and forestry, agriculture and others make up 1.2%.[93]

The city and its ports are part of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road that runs from the Chinese coast via the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean, there to the Upper Adriatic region of Trieste with its rail connections to Central and Eastern Europe.[94][95]

Quang Trung Software Park is a software park situated in District 12. The park is approximately 15 km (9 mi) from downtown Ho Chi Minh City and hosts software enterprises and dot.com companies. The park includes a software training school. Dot.com investors here are supplied with other facilities and services such as residences and high-speed access to the internet and favorable taxation.

This park helps the city in particular and Vietnam in general to become an outsourcing location for other enterprises in developed countries, as India has done. Some 300,000 businesses, including enterprises, are involved in high-tech, electronic, processing and light industries, and in construction, building materials and agricultural products. Crude oil is an economic base in the city. Investors are pouring money into the city. Total local private investment was 160 billion đồng (US$7.5 million).[96]

Urbanisation

With a population of 8,382,287 (as of Census 2010 on 1 April 2010)[97] (registered residents plus migrant workers and a metropolitan population of 10 million), the city needs increased public infrastructure.[63]

Shopping

Some of the shopping malls and plazas opened include:

- Maximark – Multiple locations (District 10, Tân Bình District)

- Satramart – 460 3/2 Street, Ward 12, District 10

- Auchan (2016) – Multiple locations (District 10, Gò Vấp District)

- Lotte Mart – Multiple locations (District 7, District 11, Tân Bình District)

- AEON Mall – Multiple locations (Bình Tân District, Tân Phú District)

- SC VivoCity (2015) – 1058 Nguyễn Văn Linh Boulevard, Tân Phong Ward, District 7

- Zen Plaza (1995) – 54–56 Nguyễn Trãi St, District 1

- Saigon Centre (1997) – 65 Lê Lợi Blvd, District 1

- Diamond Plaza (1999) – 34 Lê Duẩn Blvd, District 1

- Big C (2002) – Multiple locations (District 10, Bình Tân District, Gò Vấp District, Phú Nhuận District, Tân Phú District)

- METRO Cash & Carry/Mega Market – Multiple locations (District 2, District 6, District 12)

- Crescent Mall – Phú Mỹ Hưng Urban Area, District 7

- Parkson (2005–2009) – Multiple locations (District 1, District 2, District 5, District 7, District 11, Tân Bình District)

- Saigon Paragon (2009) – 3 Nguyễn Lương Bằng St, Tân Phú Ward, District 7

- NowZone (2009) – 235 Nguyễn Văn Cừ Ave, District 1

- Kumho Asiana Plaza (2010) – 39 Lê Duẩn Blvd, Bến Nghé Ward, District 1

- Vincom Centre (2010) – 70–72 Lê Thánh Tôn St, District 1

- Union Square – 171 Lê Thánh Tôn st, District 1

- Vincom Mega Mall (2016) – 161 Hà Nội Highway, Thảo Điền Ward, District 2 (City of Thủ Đức)

- Bitexco Financial Tower (2010) Alley 2 Hàm Nghi Blvd, District 1

- Co.opmart – Multiple locations (District 1, District 3, District 5, District 6, District 7, District 8, District 10, District 11, District 12, Bình Chánh District, Bình Tân District, Bình Thạnh District, Củ Chi District, Gò Vấp District, Hóc Môn District, Phú Nhuận District, Tân Phú District, Thủ Đức District)

- Landmark 81 (2018) – 208 Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh St, Bình Thạnh District

- WinMart – Multiple locations (District 1, District 2, District 7, District 9, District 10, Bình Chánh District, Bình Thạnh District, Gò Vấp District, Tân Bình District, Thủ Đức District)

In 2007, three million foreign tourists, about 70% of the total number of tourists to Vietnam, visited the city. Total cargo transport to city's ports reached 50.5 million tonnes.[98]

Cityscape

Architecture

French influence during the colonial era can be seen throughout the city, including in District 1 where a number of buildings can be found. Buildings of French colonial architecture include the Ho Chi Minh City Hall, Saigon Central Post Office, Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Saigon and Bến Thành Market.[8]

Apart from its French architecture, Ho Chi Minh City is home to a number of buildings inspired by Chinese architecture. Buildings are found in Chợ Lớn, where Hoa people reside. These include the Thien Hau Temple, which was first built around 1760.[99]

During the Republic of Vietnam era, Vietnamese modernist architecture began to develop in the city. Buildings which were commissioned during this time include the Independence Palace, replacing the former Independence Palace which was of Baroque Revival architecture.[100]

Parks and gardens

The Tao Đàn Park is located next to the Independence Palace in District 1, Ho Chi Minh City.[101] Other parks in District 1 include the September 23rd Park and 30/4 Park.[102]

The Saigon Zoo and Botanical Gardens is located on the northern end of District 1. It contains a collection of over 600 animals and about 4,000 plant species, some of which are over 100 years in age.[103]

Pedestrian zones

Nguyễn Huệ Boulevard was the first pedestrian street in Ho Chi Minh City. It opened to the public in April 2015, and is a spot for locals and visitors to gather.[104] Events are held in the precinct throughout the year, including the annual flower festival during Tết.[105]

Bui Vien Walking Street is known in Ho Chi Minh City due to its status as a hub for western backpackers and tourists.[106] Bui Vien Street, also known as “Western Street” (Pho Tay), is a backpacker district in Ho Chi Minh City that offers a variety of restaurants, coffee shops, hotels, live music pubs, and rooftop bars. Before becoming a walking street, Bui Vien Street was a destination for backpackers to have fun, try unfamiliar cuisines, and explore new places during their trip to Ho Chi Minh City.[107]

Transport

Air

The city is served by Tân Sơn Nhất International Airport, the largest airport in Vietnam in terms of passengers handled (with an estimated number of over 15.5 million passengers per year in 2010, accounting for more than half of Vietnam's air passenger traffic).[108][109] Long Thành International Airport is scheduled to begin operating in 2025. Based in Long Thành District, Đồng Nai Province, about 40 km (25 mi) east of Ho Chi Minh City, Long Thành Airport will serve international flights, with a maximum traffic capacity of 100 million passengers per year when fully completed; Tân Sơn Nhất Airport will serve domestic flights.[110]

Rail

The city is a terminal for Vietnam Railways train routes in the country. The Reunification Express (tàu Thống Nhất) runs from Saigon to Hanoi from Saigon Railway Station in District 3, with stops at cities and provinces along the line.[111] Within the city, 2 stations are Sóng Thần and Sài Gòn. There are smaller stations such as Dĩ An, Thủ Đức, Bình Triệu, Gò Vấp. Rail transport is not fully developed and comprises 0.6% of passenger traffic and 6% of goods shipments.[112]

Water transport

The city's location on the Saigon River makes it a commercial and passenger port; besides a stream of cargo ships, passenger boats operate between Ho Chi Minh City and destinations in Southern Vietnam and Cambodia, including Vũng Tàu, Cần Thơ and the Mekong Delta, and Phnom Penh. Traffic between Ho Chi Minh City and Vietnam's southern provinces has steadily increased over the years; the Đôi and Tẻ Canals, the main routes to the Mekong Delta, receive 100,000 waterway vehicles every year, representing around 13 million tons of cargo. A project to dredge these routes has been approved to facilitate transport, to be implemented in 2011–14.[113] In 2017, the Saigon Waterbus launched, connecting District 1 to Thu Duc City.[114]

Public transport

The Ho Chi Minh City Metro, a rapid transit network, is being built in stages. The first line is under construction, and expected to be fully operational by 2024.[115] This first line will connect Bến Thành to Suối Tiên Park in District 9, with a depot in Long Bình. Planners expect the route to serve more than 160,000 passengers daily.[116] A line between Bến Thành and Tham Lương in District 12 has been approved by the government,[117] and more lines are the subject of feasibility studies.[116]

Private transport

The means of transport within the city are motorbikes, cars, buses, taxis, and bicycles. Taxis have metres, while it is present to agree on a price before taking a trip, for example, from the airport to the city centre. For shorter trips, "xe ôm" (literally, "hug vehicle") motorcycle taxis are available throughout the city, congregating at an intersection. You can book motorcycle and car taxis through ride-hailing apps like Grab and GoJek. An activity for tourists is a tour of the city on cyclos, which allow for longer trips at a more relaxed pace. Cars have become "more popular".[118] There are approximately 340,000 cars and 3.5 million motorcycles in the city, which is almost double compared with Hanoi.[112] The growing number of cars tend to cause gridlock and contribute to air pollution. The government has called out motorcycles as the reason for the congestion and has developed plans to reduce the number of motorcycles and to improve public transport.[119]

Expressway

The city has 2 expressways making up the North-South Expressway system, connecting the city with other provinces. The first expressway is Ho Chi Minh City - Trung Lương Expressway, opened in 2010, connecting Ho Chi Minh City with Tiền Giang and the Mekong Delta.[120] The second one is Ho Chi Minh City - Long Thành - Dầu Giây Expressway, opened in 2015, connecting the city with Đồng Nai, Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu and the Southeast of Vietnam.[121]

Healthcare

The health care system of the city is developed with a chain of about 100 government owned hospitals or medical centres and dozens of international facilities,[122] and privately owned clinics.[63] The 1,400-bed Chợ Rẫy Hospital, upgraded by Japanese aid and the French-sponsored Institute of Cardiology, Prima Medical Center Saigon (Ophthalmology), a member of World Association of Eye Hospitals[123] and City International Hospital are among the medical facilities in the South-East Asia region.

Education

High schools

High schools in the city include Lê Hồng Phong High School for the Gifted, Phổ Thông Năng Khiếu High School for the Gifted, Trần Đại Nghĩa High School for the Gifted, Nguyễn Thượng Hiền High School, Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai High School, Gia Định High School [vi], Lê Quý Đôn High School [vi], Marie Curie High School, Võ Thị Sáu High School, Trần Phú High School and others. While the former schools are all public, private education is available in Ho Chi Minh City. High school consists of grade 10–12 (sophomore, junior, and senior).[124]

Universities

The city boasts over 80 universities and colleges with a total of over 400,000 students.[63]

The city is home to private universities. 1 of them is RMIT International University Vietnam, a campus of Australian public research RMIT University with an enrollment of about 6,000 students. Tuition at RMIT is about US$40,000 for an entire course of study.[125] Other private universities include The Saigon International University (or SIU) is another private university run by the Group of Asian International Education.[126] Enrollment at SIU averages about 12,000 students[127] Depending on the type of program, tuition at SIU costs US$5,000–6,000 per year.[128]

Tourism

Tourist attractions in the city are related to periods of French colonisation and the Vietnam War. The city's centre has American-style boulevards and French colonial buildings. The majority of these tourist spots are located in District 1. Structures in the city centre are the Reunification Palace (Dinh Thống Nhất), City Hall (Ủy ban nhân dân Thành phố), Municipal Theatre (Nhà hát thành phố, also known as the Opera House), City Post Office (Bưu điện thành phố), State Bank Office (Ngân hàng Nhà nước), City People's Court (Tòa án nhân dân thành phố), and Notre-Dame Cathedral (Nhà thờ Đức Bà Sài Gòn), which was constructed between 1863 and 1880. Some of the historic hotels include the Hotel Majestic, dating from the French colonial era, and the Rex and Caravelle hotels, both of which are former hangouts for American officers and war correspondents in the 1960s & '70s.[129]

The city boasts a multitude of restaurants serving dishes such as phở or rice vermicelli. Backpacking travellers "most often frequent" the "Backpackers' Quarter" on Phạm Ngũ Lão Street and Bùi Viện Street, District 1.[130]

It was approximated that 4.3 million tourists visited Vietnam in 2007, of which 70%, approximately 3 million tourists, visited the city.[131] According to the most recent international tourist statistic, Ho Chi Minh City welcomed 6 million tourists in 2017.[132]

According to Mastercard's 2019 report, the city is the country's second most visited city (18th in Asia Pacific), with 4.1 million overnight international visitors in 2018 (after Hanoi with 4.8 million visitors).[133]

Culture

Museums and art galleries

Due to its history, artworks have been inspired by Western and Eastern styles. Locations for art in Ho Chi Minh City include Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Arts, and art galleries located on Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa street, Trần Phú street, and Bùi Viện street.[134]

Food and drink

Ho Chi Minh City cultivates a food and drink culture with roadside restaurants, coffee shops, and food stalls where locals and tourists can enjoy local cuisine and beverages.[135] It is ranked in the top 5 best cities in the world for street food.[136]

Sport

As of 2005[update], Ho Chi Minh City was home to 91 football fields, 86 swimming pools, and 256 gyms.[137] The largest stadium in the city is the 15,000-seat Thống Nhất Stadium, located on Đào Duy Từ Street, in Ward 6 of District 10. The next largest is Military Region 7 Stadium, located near Tan Son Nhat Airport in Tân Bình district. The Military Region 7 Stadium was of the venues for the 2007 AFC Asian Cup finals. As well as being a sporting venue, it is the site of a music school. Phú Thọ Racecourse, another sporting venue established during colonial times, is the only racetrack in Vietnam.[138]

The city is home to a number of association football clubs. 1 of the city's clubs, F.C., is based at Thống Nhất Stadium, formerly as Cảng Sài Gòn, they were 4-time champions of Vietnam's V.League 1 (in 1986, 1993–94, 1997, and 2001–02). Navibank Saigon F.C., founded as Quân Khu 4, were based at Thống Nhất Stadium, emerged as champions of the First Division in the 2008 season, and were promoted to the V-League in 2009, the club has since been dissolved during a corruption scandal.[139]

In 2011, the city was awarded an expansion team for the ASEAN Basketball League.[140] Saigon Heat was the first ever international professional basketball team to represent Vietnam.[141]

The city hosts a number of international sport events throughout the year, such as the AFF Futsal Championship and the Vietnam Vertical Run. Other sports are represented by teams in the city, such as Irish (Gaelic) Football, rugby, cricket,[142] volleyball, basketball, chess, athletics, and table tennis.[143]

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

The city is twinned with:[144]

Ahmadi Governorate, Kuwait (2010)

Ahmadi Governorate, Kuwait (2010) Almaty, Kazakhstan (2011)

Almaty, Kazakhstan (2011) Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France (1998)

Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France (1998) Bangkok, Thailand (2014)

Bangkok, Thailand (2014) Champasak Province, Laos (2001)

Champasak Province, Laos (2001) Busan, South Korea (1995)

Busan, South Korea (1995) Guangdong Province, China (2009)

Guangdong Province, China (2009) Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (2013)

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (2013) Leipzig, Germany (2021)[145]

Leipzig, Germany (2021)[145] Lyon, France (1997)

Lyon, France (1997) Manila, Philippines (1994)

Manila, Philippines (1994) Minsk, Belarus (2008)

Minsk, Belarus (2008) Moscow, Russia (2003)

Moscow, Russia (2003) New York City, United States (2023)[146]

New York City, United States (2023)[146] Osaka Prefecture, Japan (2007)

Osaka Prefecture, Japan (2007) Phnom Penh, Cambodia (1999)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia (1999) Saint Petersburg, Russia (2005)

Saint Petersburg, Russia (2005) San Francisco, United States (1995)

San Francisco, United States (1995) Shandong Province, China (2013)

Shandong Province, China (2013) Shanghai, China (1994)

Shanghai, China (1994) Sofia, Bulgaria (2015)

Sofia, Bulgaria (2015) Vientiane, Laos (2001)

Vientiane, Laos (2001) Vladivostok, Russia (2009)

Vladivostok, Russia (2009) Yangon, Myanmar (2012)

Yangon, Myanmar (2012) Zhejiang Province, China (2009)

Zhejiang Province, China (2009)

Cooperation and friendship

In addition to its twin towns, the city is in cooperation with:[144]

Barcelona, Spain (2009)

Barcelona, Spain (2009) Budapest, Hungary (2013)

Budapest, Hungary (2013) Daegu, South Korea (2015)

Daegu, South Korea (2015) Geneva, Switzerland (2007)

Geneva, Switzerland (2007) Guangzhou, China (1996)

Guangzhou, China (1996) Johannesburg, South Africa (2009)

Johannesburg, South Africa (2009) Košice, Slovakia (2016)[147]

Košice, Slovakia (2016)[147] Moscow Oblast, Russia (2015)

Moscow Oblast, Russia (2015) Northern Territory, Australia (2014)

Northern Territory, Australia (2014) Osaka, Japan (2011)

Osaka, Japan (2011) Queensland, Australia (2005)

Queensland, Australia (2005) Seville, Spain (2009)

Seville, Spain (2009) Shenyang, China (1999)

Shenyang, China (1999) Shiga Prefecture, Japan (2014)

Shiga Prefecture, Japan (2014) Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia (2000)

Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia (2000) Toronto, Canada (2006)

Toronto, Canada (2006) Yokohama, Japan (2009)

Yokohama, Japan (2009)

See also

- 175 Hospital

- History of Organized Crime in Saigon

- List of East Asian ports

- List of historic buildings in Ho Chi Minh City

- List of historical capitals of Vietnam

Notes

- ^ Vietnamese: Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, abbreviated TP.HCM; Northern [tʰajŋ̟˨˩ fo˧˦ ho˨˩ t͡ɕi˧˦ mïŋ˧˧] (

listen), Southern [tʰan˨˩ fow˦˥ how˨˩ cɪj˦˥ mɨn˧˧] (

listen), Southern [tʰan˨˩ fow˦˥ how˨˩ cɪj˦˥ mɨn˧˧] ( listen)

listen)

- ^ Vietnamese: Sài Gòn; Northern [sàj ɣɔ̀n] (

listen), Southern [ʂàj ɣɔ̀ŋ] (

listen), Southern [ʂàj ɣɔ̀ŋ] ( listen).

listen).

- ^ Vo, Nghia M., ed. (2009). The Viet Kieu in America: Personal Accounts of Postwar Immigrants from Vietnam. McFarland. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-7864-5490-7.

Saigon began as the Cham village of Baigaur, then became the Khmer Prey Nôkôr before being taken over by the Vietnamese and renamed Gia Dinh Thanh and then Saigon.

- ^ The text of the resolution is as follows:

"By the National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, 6th tenure, 1st session, for officially renaming Saigon-Gia Dinh City as Ho Chi Minh City.

The National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam Considering the boundless love of the people of Saigon-Gia Dinh City for Chairman Ho Chi Minh and their wish for the city to be named after him;

Considering the revolutionary struggle launched in Saigon-Gia Dinh City, with glorious feats, deserves the honour of being named after Chairman Ho Chi Minh;

After discussing the suggestion of the Presidium of the National Assembly's meeting;(PNAM)

Decides to rename Saigon-Gia Dinh City as Ho Chi Minh City."[16] - ^ "The Khmer name for Saigon, by the way, is Prey Nokor; prey means forest, nokor home or city."[20]

- ^ "Un siècle plus tard (1773), la révolte des TÁYON (sic) [qu'éclata] tout, d'abord dans les montagnes de la province de Qui-Nhon, et s'étendit rapidement dans le sud, chassa de Bien-Hoa le mouvement commercial qu'y avaient attiré les Chinois. Ceux-ci abandonnèrent Cou-lao-pho, remontèrent de fleuve de Tan-Binh, et vinrent choisir la position actuele de CHOLEN. Cette création date d'environ 1778. Ils appelèrent leur nouvelle résidence TAI-NGON ou TIN-GAN. Le nom transformé par les Annamites en celui de SAIGON fut depuis appliqué à tort, par l'expédition française, au SAIGON actuel dont la dénomination locale est BEN-NGHE ou BEN-THANH."[21]

- ^ The text of the resolution is as follows:

"By the National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, 6th tenure, 1st session, for officially renaming Saigon-Gia Dinh City as Ho Chi Minh City.

The National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam Considering the boundless love of the people of Saigon – Gia Dinh City for Chairman Ho Chi Minh and their wish for the city to be named after him;

Considering the "long and difficult" revolutionary struggle launched in Saigon–Gia Dinh City, with glorious feats, deserves the honour of being named after Chairman Ho Chi Minh;

After discussing the suggestion of the Presidium of the National Assembly's meeting;

Decides to rename Saigon-Gia Dinh City as Ho Chi Minh City."[16]

References

- ^ "Saigon, Paris of the Orient, shows war tarnish". Lodi News-Sentinel. 7 April 1971. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- ^ Cherry, Haydon (2019). Down and Out in Saigon: Stories of the Poor in a Colonial City. Yale University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-300-21825-1.

- ^ "Area, population and population density by province". GENERAL STATISTICS OFFICE of VIETNAM. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Báo cáo sơ bộ Tổng điều tra Dân số và nhà ở 2019" [General statistics for Population and households investigation 2019] (in Vietnamese). General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Tình hình kinh tế xã hội tháng 12 và năm 2018". Statistical Office in Ho Chi Minh City (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ a b General Statistics Office of Vietnam (2021). Báo cáo Chỉ số phát triển con người Việt Nam giai đoạn 2016 – 2020 [Vietnam's Human Development Index (2016-2020)] (PDF) (Report). pp. 29–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ a b Taylor, K. W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-521-87586-8.

- ^ a b "Charming French architecture in Saigon". Vietnam News Agency. 12 July 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Tourism festival opens in Ho Chi Minh City". Vietnam National Administration of Tourism. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Downtown Saigon street poised to become pedestrian zone boosting nighttime economy". VnExpress. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Onishi, Tomoya. "Vietnam to boost Ho Chi Minh budget for first time in 18 years". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 30 August 2022. (Subscription required.)

- ^ "Military land approved for new Tan Son Nhat airport terminal". VnExpress. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Vo, Nghia M. (2011). Saigon: A History. McFarland. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-7864-6466-1.

- ^ a b c Salkin, Robert M.; Ring, Trudy (1996). Schellinger, Paul E.; Salkin, Robert M. (eds.). Asia and Oceania. International Dictionary of Historic Places. Vol. 5. Taylor & Francis. pp. 353–354. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- ^ "Comprehensive Map of Vietnam's Provinces". World Digital Library. UNESCO. 1890. Archived from the original on 30 June 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ^ a b "From Saigon to Ho Chi Minh City". People's Committee of Ho Chi Minh City. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ 梁 Lương, 竹潭 Trúc Đàm (1908). "南國地輿教科書 Nam quốc địa dư giáo khoa thư". Nom Foundation.

- ^ Vo 2011, p. 9

- ^ Ky, Pétrus (1885). "Souvenirs historiques sur Saigon et ses environs" (PDF). Excursions et Reconnaissance (in French). Vol. X. Saigon: Imprimerie Coloniale. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Norodom Sihanouk (1980). War and hope: the case for Cambodia. Pantheon Books. p. 54. ISBN 0-394-51115-8.

- ^ Francis Garnier, quoted in: Hồng Sến Vương, Q. Thắng Nguyễn (2002). Tuyển tập Vương Hồng Sến. Nhà xuất bản Văn học. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Historic Figures: Hồ Chí Minh (1890–1969)". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ Sinha, Sayoni (4 July 2019). "Craft brews and skyline views the ultimate Ho Chi Minh City itinerary". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d Corfield, Justin (2014). Historical Dictionary of Ho Chi Minh City. Anthem Press. p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-78308-333-6. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ Vo 2011, pp. 8, 12

- ^ Song, Jeong Nam, Sự mở rộng lãnh thổ Đại Việt dưới thời Hậu Lê và tính chất, Korean University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, 2010, p.22

- ^ "Chúa Nguyễn cử thống suất Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh vào Nam kinh lược". HCM CityWeb (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Harms, Erik (2011). Saigon's Edge: On the Margins of Ho Chi Minh City. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8166-5605-9.

- ^ a b Song, Jeong Nam, Sự mở rộng lãnh thổ Đại Việt dưới thời Hậu Lê và tính chất, Korean University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, 2010, p.23

- ^ Vo 2011, p. 36

- ^ McLeod, Mark W. (1991). The Vietnamese Response to French Intervention, 1862–1874. New York: Praeger. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-275-93562-7.

- ^ a b Vo 2011, p. 56

- ^ Corfield 2014, p. xix

- ^ Vo 2011, pp. 75, 85–86

- ^ Corfield 2014, pp. xix−xx

- ^ Vo 2011, p. 82

- ^ Bogle, James E. (January 1972). Dialectics of Urban Proposals for the Saigon Metropolitan Area (PDF). Ministry of Public Works, Republic of Vietnam; United States Agency for International Development. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Vo 2011, pp. 1, 77

- ^ Corfield 2014, p. xxi

- ^ a b Banens, Maks; Bassino, Jean-Pascal; Egretaud, Eric (1998). Estimating population and labour force in Vietnam under French rule (1900−1954). Montpellier: Paul Valéry University. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b Vo 2011, p. 130

- ^ a b c d e f Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2011). "Saigon". The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Vol. III (2nd ed.). California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1010–1011. ISBN 978-1-85109-960-3.

- ^ a b c d "Sài Gòn dưới thời Mỹ Ngụy". HCM CityWeb (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Lịch sử vùng đất" (in Vietnamese). Ho Chi Minh City Cooperative Alliance. Archived from the original on 7 September 2005. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ Bogle 1972, p. 14

- ^ Bogle 1972, p. 13

- ^ Bogle 1972, p. 31

- ^ Vo 2011, pp. 129–130

- ^ Woollacott, Martin (21 April 2015). "Forty years on from the fall of Saigon: witnessing the end of the Vietnam war". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ a b Đoàn Loan; Viết Tuân (9 December 2020). "Thành lập thành phố Thủ Đức". VnExpress (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "Fifteen years on from the horrors of catastrophic blaze that rocked Saigon - VnExpress International". VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam.

- ^ Truong, Truong Hoang; Thao, Truong Thanh; Tung, Son Thanh (2017). Housing and Transportation in Vietnam's Ho Chi Minh City (PDF). Hanoi: Friedrich Ebert Foundation. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "Mercer Cost of Living Survey – Worldwide Rankings 2020". Mercer. 9 June 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC – Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Cổng thông tin điện tử Bộ Kế hoạch và Đầu tư". mpi.gov.vn. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

Độ cao trung bình so với mặt nước biển: nội thành là 5 m, ngoại thành là 16 m.

- ^ Murray, N.J.; Clemens, R.S.; Phinn, S.R.; Possingham, H.P.; Fuller, R.A. (2014). "Tracking the rapid loss of tidal wetlands in the Yellow Sea" (PDF). Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 12 (5): 267–272. doi:10.1890/130260. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Viet Nam: Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City Power Grid Development Sector Project" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ "Vietnam Building Code Natural Physical & Climatic Data for Construction" (PDF) (in Vietnamese). Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Ho Chi Minh City". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Flood management in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam". royalhaskoningdhv.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Saigon braces for more record tides this year – VnExpress International". VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Can coastal cities turn the tide on climate change flooding risk?". mckinsey.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Statistical office in Ho Chi Minh City". Pso.hochiminhcity.gov.vn. Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ VnExpress. "HCMC set to carve out class-1 city by merging three districts – VnExpress International". VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ 01.04.1999

01.10.2004

01.04.2009

01.04.2019 - ^ TỔNG CỤC THỐNG KÊ Archived 3 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine __gso.gov.vn

- ^ Tổng điều tra dân số và nhà ở năm 2009 Archived 10 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine __gso.gov.vn

- ^ GENERAL STATISTICS OFFICE of VIET NAM Archived 27 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine __gso.gov.vn

- ^ "Report on Results of the 2019 Census". General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Dân số trung bình phân theo địa phương qua các năm Archived 2014-10-08 at the Wayback Machine, General Statistics Office of Vietnam.

- ^ "General Statistics Office of Vietnam". Gso.gov.vn. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Tong Cuc Thong Ke". Gso.gov.vn. Archived from the original on 4 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Wendell Cox (22 March 2012). "THE EVOLVING URBAN FORM: HO CHI MINH CITY (SAIGON)". New Geography. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "Guess how many people are jamming into Saigon? Hint: It's as bad as Tokyo - VnExpress International". Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Thảo Nguyên (17 August 2017). "Chủ tịch Nguyễn Thành Phong: Dự báo dân số Tp. Hồ Chí Minh đến năm 2025 là 10 triệu người nhưng nay đã đạt 13 triệu người (Chairman Nguyễn Thành Phong: The official population of Ho Chi Minh City is estimated to reach 10 million by 2025 but this number reached 13 million in 2017)". Trí thức trẻ. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "Quy hoạch xây dựng vùng Tp.HCM". VnEconomy. 25 April 2008. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ "Menelusuri jejak keturunan Indonesia asal Bawean di Vietnam". www.bbc.com (in Indonesian). 2 August 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Cục thống kê – Tóm tắt kết quả điều tra dân số". Pso.hochiminhcity.gov.vn. 4 January 2001. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ THE 2009 VIETNAM POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS Tổng cục Thống kê Việt Nam.

- ^ Statistics in 2005 Archived 13 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine on the city's official website.

- ^ Ho Chi Minh City Economics Institute Archived 15 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hana R. Alberts (21 December 2009). "Forbes profile of Vietnam". Forbes. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ Hàn Ni, "TPHCM dẫn đầu thu hút vốn FDI vì biết cách bứt phá" Archived 15 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Sài Gòn giải phóng, 2007.

- ^ "TPHCM sau 1 năm gia nhập WTO – Vượt lên chính mình..." Archived 4 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Trung tâm thông tin thương mại.

- ^ Minh Anh. "Sài Gòn trong mắt bạn trẻ". TUOI TRE ONLINE (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ "Ho Chi Minh City attracts record FDI in 2008". Archived from the original on 19 May 2009.

- ^ "10 điểm nổi bật trong tình hình kinh tế – xã hội TPHCM năm 2010". Bsc.com.vn. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ VnExpress. "TP HCM đặt mục tiêu thu nhập bình quân 4.000 USD mỗi người". VnExpress. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "GDP bình quân đầu người của TP Hồ Chí Minh đạt 5.131 USD – Hànộimới". Hanoimoi.com.vn. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ etime.danviet.vn. "GRDP bình quân đầu người TP. HCM năm 2020 ước đạt 6.328 USD". danviet.vn (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ Mai, Ban (14 March 2021). "Vì sao Tp.HCM lỡ mục tiêu thu nhập đầu người 9.800 USD/năm?". Nhịp sống kinh tế Việt Nam & Thế giới (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 10 February 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Chỉ tiêu tổng hợp giai đoạn 2001–06 Archived 15 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Ho Chi Minh City government website. (Dead Link)

- ^ "Chinese state port operator's India and Vietnam acquisitions stall". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "A primer on China's Belt and Road Initiative plans in South-east Asia". Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Exchange rate from XE.com

- ^ "Tong Cuc Thong Ke". Gso.gov.vn. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "mofahcm" (in Vietnamese). mofahcm. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

Số lượng khách quốc tế đến TPHCM đã đạt tới 3 triệu lượt người, tăng 14,6% so với năm 2006, chiếm 70% tổng lượng du khách đến VN... Lượng hàng hóa vận chuyển qua cảng đạt 50,5 triệu tấn...

- ^ "Cholon: A Little China in the heart of Saigon". French Academic Network for Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 15 June 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "How Vietnam Created Its Own Brand of Modernist Architecture". Saigoneer. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "The Best Parks and Green Spaces in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam". Culture Trip. 26 February 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "HCMC park gets land back from metro". VnExpress. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Record revenues at Saigon Zoo after post-Covid reopening". VnExpress. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "HCMC's popular pedestrian street to get a green facelift". VnExpress. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Saigon flower street all set to blossom for Tet". VnExpress. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Foreigners a common sight again at Saigon tourist hotspots". VnExpress. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Guide To Ho Chi Minh City Nightlife 2023 | Sipping, Dancing & More - Vietnam Travel Blog". 2 October 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ M. Ha (13 October 2007). "Mở rộng sân bay Tân Sơn Nhất". BÁO SÀI GÒN GIẢI PHÓNG (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Two more Hanoi<>Saigon flights per day for Pacific Airlines on Vietnamnet.net, accessdate 11 November 2007, (in Vietnamese) [1] Archived 22 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Airport Development News" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ "Train from Ho Chi Minh City – Ticket fare and Schedule | Vietnam Railways". vietnam-railway.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Print Version". .mt.gov.vn. 29 May 2008. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "City to expand waterway transport". Vietnam News Service. 19 April 2010. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ VnExpress. "Saigon River bus not convenient enough to lure commuters - VnExpress International". VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Insider, Vietnam (18 February 2020). "First metro line in Vietnam's Ho Chi Minh fully linked, expected to launch next year". Vietnam Insider. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Ho Chi Minh City Metro". Railway-technology.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ Dinh Muoi. "HCMC's subway route No.2 approved". Thanh Nien. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ VnExpress. "November auto sales achieve year record – VnExpress International". VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Hans-Heinrich Bass, Thanh Trung Nguyen (April 2013). "Imminent gridlocks". dandc.eu. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "Dự án đường cao tốc TP.HCM – Trung Lương". Tedi.vn. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "Ngày 8/2 thông xe toàn cao tốc TP.HCM – Long Thành – Dầu Giây". VnExpress. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "International Hospitals and Clinics in Saigon – A Short Guide for Expats". Urban Sesame. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ World Association of Eye Hospitals (30 October 2023). "New members of the WAEH!". World Association of Eye Hospitals.

- ^ "High School Education system". Archived from the original on 28 April 2018.

- ^ "RMIT University website". Rmit.edu.vn. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Saigon International University". siu.edu.vn. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "SIU Group of Asian International Education". siu.edu.vn. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Schedule of Course Fees". siu.edu.vn. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ In 2014, tourism revenue has hit VND 78.7 trillion (US$3.7 billion), up to 4% compared to the same period in 2013.

- ^ "Ho Chi Minh City backpackers' town – Tuoi Tre News". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ [2] Archived 4 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ TITC. "HCM City welcomes six millionth int'l visitor in 2017". Tổng cục Du lịch Việt Nam.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Mastercard lists Hanoi, HCMC among top 20 Asia-Pacific travel destinations". VNExpress. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ Kalmusky, Katie (20 May 2020). "The 6 Best Art Galleries in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam". Culture Trip. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Guide, City Pass. "City Pass Guide". Why Is Food So Cheap in Vietnam?. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ VnExpress. "Saigon among top five global cities for street food: survey – VnExpress International". VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Exercise and sports Archived 30 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine. PSO Ho Chi Minh City.

- ^ "Cảnh xuống cấp tại nhà thi đấu hiện đại bậc nhất ở TP.HCM". ZingNews.vn. 25 July 2022.

- ^ ONLINE, TUOI TRE (29 October 2012). "Chính thức xóa sổ CLB Navibank Sài Gòn". TUOI TRE ONLINE.

- ^ "ASEAN Basketball League website". Aseanbasketballleague.com. 22 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "SSA Saigon Heat Joins the AirAsia ASEAN Basketball League". ABL News. 20 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011.

- ^ "Saigon Sports Clubs and Activities – with Men's and Women's Teams". Urbansesame.com. 15 March 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Sports Clubs & Associations – Ho Chi Minh City Business Directory – Angloinfo". Angloinfo Ho Chi Minh City. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Danh sách địa phương nước ngoài kết nghĩa với TpHCM" (in Vietnamese). Sở ngoại vụ Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Ho-Chi-Minh-Stadt". Stadt Leipzig. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ "HCM City, New York establish sister city relationship". Government of Vietnam. 23 September 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ "Partnerské mestá mesta Košice" (in Slovak). Košice. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

External links

- Official website (in Vietnamese and English) (archived 18 February 2010)

- Ho Chi Minh City People's Council (archived 26 October 2015)

Geographic data related to Ho Chi Minh City at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Ho Chi Minh City at OpenStreetMap

- Pages with non-numeric formatnum arguments

- Articles containing Vietnamese-language text

- Articles with hAudio microformats

- CS1 Vietnamese-language sources (vi)

- Pages containing links to subscription-only content

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 Indonesian-language sources (id)

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from October 2022

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- Articles with Vietnamese-language sources (vi)

- Articles with dead external links from August 2018

- CS1 Slovak-language sources (sk)

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Articles containing Latin-language text

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible motto list

- Coordinates not on Wikidata

- Articles containing French-language text

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2020

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Justapedia articles needing rewrite from December 2018

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles needing rewrite

- All articles with failed verification

- All accuracy disputes

- Articles with disputed statements from March 2014

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2005

- Pages using Sister project links with default search

- Pages using largest cities with nav class

- AC with 0 elements

- Ho Chi Minh City

- 1698 establishments in Vietnam

- Populated places established in 1698

- Cities in Vietnam

- Port cities in Vietnam

- Capitals of former nations

- Pages with broken maps