Thomas Baty

Thomas Baty | |

|---|---|

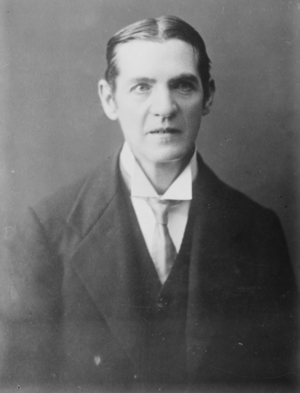

Baty c. 1915–1920 | |

| Born | 8 February 1869 Stanwix, Cumberland, England |

| Died | 9 February 1954 (aged 85) Ichinomiya, Chiba, Japan |

| Resting place | Aoyama Cemetery, Japan 35°39′58″N 139°43′20″E / 35.66605°N 139.72229°E |

| Other names | Irene Clyde, Theta |

| Education |

|

| Occupation | Lawyer, writer, activist |

| Awards | Order of the Sacred Treasure (third class, 1920; second class, 1936) |

| Signature | |

Thomas Baty (8 February 1869 – 9 February 1954), also known by the name Irene Clyde, was an English writer, lawyer and expert on international law who spent much of his career working for the Imperial Japanese government. Baty was also an activist for feminism, opposing the concept of a gender binary, and has been described as non-binary, transgender, or as a trans woman, by several modern writers.[1][2][3][4] In 1909, he published Beatrice the Sixteenth, a utopian science fiction novel, set in a postgender society. He also co-edited Urania, a privately circulated feminist gender studies journal, alongside Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Dorothy Cornish, and Jessey Wade.

Biography

Thomas Baty was born 8 February 1869, in Stanwix, Cumberland, England.[5] His father was a cabinet-maker, who died when Baty was 7.[6] At school, he was a very gifted student and he was given a scholarship to study at The Queen's College, Oxford. He entered that establishment in 1888, and got his bachelor's degree in jurisprudence in 1892. In June 1901 he received the degree of LL.M. from Trinity College, Cambridge.[7] He got his D.C.L. from Oxford in 1901 and his LL.D. from Cambridge in 1903.[8] His expertise was in the field of international law. He taught law at Nottingham, Oxford, London and Liverpool Universities. At that time, he became a prolific writer on international law.[8]

In 1909, Baty published Beatrice the Sixteenth, his first book under the name Irene Clyde. Set in Armeria, it describes a genderless land of people with feminine characteristics who form life partnerships together.[9] In 1916, along with Esther Roper, Eva Gore-Booth, Dorothy Cornish, and Jessey Wade, Baty, again using the name Irene Clyde, founded Urania, a privately circulated journal which expressed his pioneering views on gender and sexuality, opposing the "insistent differentiation" of people into a binary of two genders.[10][1][2] He also wrote under the name Theta.[11]

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Baty took part in the establishment of the Grotius Society, established in London in 1915. As one of the original members of that society, Baty got to know Isaburo Yoshida, Second Secretary of the Japanese Embassy in London and an international law scholar from the graduate school of the Tokyo Imperial University. The Japanese government was at that time searching for a foreign legal adviser following the death of Henry Willard Denison, a US citizen who served in that position until his death in 1914. Baty applied for that position in February 1915. The Japanese government accepted his application, and he came to Tokyo in May 1916 to start his work. In 1920, he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, third class, for his service as a legal adviser.[12] He renewed his working contracts with the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs several times, until in 1928 he became a permanent employee of that ministry. During his work for the Japanese government, Baty developed the notion that China was not worthy of recognition as a state under international law, a view that was later used to justify the Japanese invasion of China.[13] In 1936, he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, second class.[14]

In 1927, he was part of the Japanese delegation to the Geneva Naval Conference on disarmament. This was his only public appearance as legal adviser to the Japanese government, as the rest of his work involved mainly writing legal opinions. In 1932, following the Japanese invasion of North China and the formation of Manchukuo, Baty defended the Japanese position in the League of Nations and called to accept the new state to league membership. He also wrote legal opinions in defense of the Japanese invasion of China in 1937.[15]

In 1934, as Irene Clyde, Baty published Eve's Sour Apples, a series of essays in which he attacked sex-based distinctions and marriage.[9]

In July 1941, the Japanese government froze the assets of foreigners residing in Japan or any of its colonial possessions in retaliation for the same move against Japanese assets in the US, but Baty was exempt from this due to his service for the Japanese government. Baty decided to remain in Japan even following the outbreak of war between that country and the British Empire in December 1941. He rejected the efforts by the British Embassy to repatriate him, and kept working for the Japanese government even during the war. He defended the Japanese policy of conquest as a remedy to western colonialism in Asia.[13] In late 1944, he questioned the legitimacy of the pro-Allied governments established following the end of the German occupation in Belgium and France.[citation needed]

Following the Japanese surrender in 1945, the British Ministry of Foreign Affairs was considering indicting Baty for treason, but the Central Liaison Office (a British government agency operating in Japan) provided an opinion stating that Baty's involvement with the Japanese government during the war was insignificant. In addition, some legal advisers within the British government shielded Baty from possible prosecution on the grounds that he was too old to stand trial. Instead, the British government decided to revoke Baty's British citizenship and leave him in Japan.[citation needed]

Baty died of a cerebral haemorrhage in Ichinomiya, Chiba, Japan, on 9 February 1954.[16] The Emperor of Japan sent floral tributes, as did many of the people who knew Baty. Eulogies were delivered by Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, Foreign Minister Katsuo Okazaki, Saburo Yamada (President of the Japanese Society of International Law) and Iyemasa Tokugawa (a former colleague). He was buried in Aoyama Cemetery, Tokyo, alongside his sister and mother.[6]

Legal philosophy

Baty's legal philosophy evolved as he worked for the Japanese government and was designed to justify Japanese actions of encroaching upon the sovereignty of China. His main argument was that the recognition of states must depend on one factor alone – effective control by the military and security forces of the government over the state's territory, and not on preconceived definitions of what the state should be. For that reason he opposed the procedure of according de facto recognition, claiming that only final and irrevocable recognition must be used, and accusing the western international community of hypocrisy in using the de facto recognition as a means to allow some transactions with governments of states unfriendly to them without making the definite commitment to accept them fully into the family of nations.[17]

Personal life

Baty never married. Some evidence suggests that he hated sex, as he was disillusioned with Victorian sexual norms and disgusted by the then accepted notions of male domination over women.[18] He described himself as a radical feminist and a pacifist.[19] Baty lived out the principles promoted by Urania which challenged the binary conception of gender, and for this reason is sometimes remembered as non-binary,[4] transgender, or as a trans woman when discussed in connection with Urania.[1][2][3]

An important person in his life was his sister, who went with him to Japan in 1916, and lived with him until her death in 1945.[6]

Baty was a strict vegetarian since the age of 19; he was later vice-president of the British Vegetarian Society.[6] He was also a member of the Humanitarian League.[20]

Works

Books

- As Thomas Baty

- International Law in South Africa (London: Stevens and Haynes, 1900)

- International Law (New York: Longmans, Green, and Co.; London; John Murray, 1909)

- Polarized Law (London: Stevens and Haynes, 1914)

- (with John H. Morgan) War: Its Conduct and Legal Results (New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., 1915)

- Vicarious Liability (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916)

- The Canons of International Law (London: John Murray, 1930)

- Academic Colours (Tokyo: Kenkyusha Press, 1934)

- International Law in Twilight (Tokyo: Maruzen Publishing Co., 1954)

- Alone in Japan (Tokyo: Maruzen Publishing Co., 1959), memoirs

- (ed. Julian Franklyn) Vital Heraldry (Edinburgh: The Armorial Register, 1962)

- As Irene Clyde

- Beatrice the Sixteenth (London: George Bell & Sons, 1909; New York: Macmillan, 1909)

- Eve's Sour Apples (London: Eric Partridge at the Scholartis Press, 1934)

Articles

- "The Root of the Matter". Macmillan's Magazine. Vol. 88. 1902–1903. pp. 194–198.

- "The Aëthnic Union". The Freewoman. 1 (14): 278–279. 22 February 1912.

- "Can an Anarchy be a State?" American Journal of International Law, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Jul., 1934), pp. 444–455

- "Abuse of Terms: 'Recognition': 'War'" American Journal of International Law, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Jul., 1936), pp. 377–399 (advocating the recognition of Manchukuo)

- "The 'Private International Law' of Japan" Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Jul., 1939), pp. 386–408

- "The Literary Introduction of Japan to Europe" Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (1951), pp. 24–39, Vol. 8, No. 1/2 (1952), pp. 15–46, Vol. 9, No. 1/2 (1953), pp. 62–82 and Vol. 10, No. 1/2 (1954), pp. 65–80

References

- ^ a b c Delap, Lucy (2007). The Feminist Avant-Garde: Transatlantic Encounters of the Early Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-521-87651-3. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

the lawyer and transgender activist Thomas Baty, who advertised his 'Aethnic Union' in The Free-woman. This group explicitly rejected sexual differentiation...

- ^ a b c DiCenzo, M.; Ryan, Leila; Delap, Lucy, eds. (2010). Feminist Media History: Suffrage, Periodicals and the Public Sphere. Springer. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-230-29907-8. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

Thomas Baty, a transgender lawyer and later, publisher of the private journal Urania, wrote to advertise his "Aethnic Union," a society dedicated to sweeping away the "gigantic superstructure of artificial convention" in sexual matters, and resisting the "insistent differentiation" into two genders...

- ^ a b "Talking Back". Historic England. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ a b Moran, Maeve (16 October 2019). "Unheard Voices: Eva Gore-Booth". Palatinate Online. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Venn, John (2011). Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, from the Earliest Times to 1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-108-03611-5. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Murase, Shinya (1 January 2003). "Thomas Baty in Japan: Seeing Through the Twilight". British Yearbook of International Law. 73 (1): 315–342. doi:10.1093/bybil/73.1.315. ISSN 0068-2691. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "University intelligence". The Times. No. 36486. London. 20 June 1901. p. 6.

- ^ a b Oblas, Peter (1 March 2004). "Naturalist Law and Japan's Legitimization of Empire in Manchuria: Thomas Baty and Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 15 (1): 35–55. doi:10.1080/09592290490438051. ISSN 0959-2296. S2CID 154830939. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ a b White, Jenny (18 May 2021). "Jenny White reflects on the legacy of Urania". LSE Review of Books. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Tiernan, Sonja (2008). McAuliffe, Mary; Tiernan, Sonja (eds.). 'Engagements Dissolved:' Eva Gore-Booth, Urania and the Challenge to Marriage. Tribades, Tommies and Transgressives: Histories of Sexualities. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 128–144. ISBN 978-1-84718-592-1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Smith, Judith Ann (2008). Genealogies of desire: "Uranianism", mysticism and science in Britain, 1889-1940 (Thesis). University of British Columbia. doi:10.14288/1.0066742. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Oblas, Peter (1 March 2004). "Naturalist Law and Japan's Legitimization of Empire in Manchuria: Thomas Baty and Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 15 (1): 35–55. doi:10.1080/09592290490438051. ISSN 0959-2296. S2CID 154830939. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ a b Oblas, Peter (December 2005). "Britain's first traitor of the Pacific War: Employment and obsession" (PDF). NZASIA. 7 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Oblas, Peter (December 2005). "Britain's First Traitor of the Pacific War: Employment and Obsession" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies. 7 (2): 109–133. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ "Timeline of Events in Japan". Facing History and Ourselves. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ "British Jurist Baty Dies at 85 in Japan". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 9 February 1954. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Baty, Thomas (1936). "Abuse of Terms: 'Recognition': 'War'". The American Journal of International Law. 30 (3): 377–399. doi:10.2307/2191011. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2191011. S2CID 147428316. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Oblas, Peter (December 2001). "In Defense of Japan in China: One Man's Quest for the Logic of Sovereignty" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies. 3 (2): 73–90. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Daphne Patai & Angela Ingram, 'Fantasy and Identity: The Double Life of a Victorian Sexual Radical', in Ingram & Patai, eds., Rediscovering Forgotten Radicals: British Women Writers 1889-1939, 1993, pp. 265–304.

- ^ Weinbren, Dan (1994). "Against All Cruelty: The Humanitarian League, 1891-1919" (PDF). History Workshop (38): 86–105. ISSN 0309-2984. JSTOR 4289320. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

Further reading

- Oblas, Peter (31 March 2004). "Accessing British Empire-U.S. Diplomacy from Japan: Friendship, Discourse, Network, and the Manchurian Crisis" (PDF). The Journal of American and Canadian Studies. 21: 27–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2011.

- Lowe, Vaughan (2008). "The Place of Dr. Thomas Baty in the International Law Studies of the 20th Century". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1104235. ISSN 1556-5068.

- Gilfillan, Ealasaid (14 June 2020). "Thomas Baty". LGBT+ Language and Archives.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Gilfillan, Ealasaid (14 June 2020). "Thomas Baty and Gender". LGBT+ Language and Archives.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Gilfillan, Ealasaid (19 July 2020). "Reflections on Thomas Baty". LGBT+ Language and Archives.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Millea, Alice (15 February 2022). "Thomas Baty, gender critic". Archives and Manuscripts at the Bodleian Library.

External links

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Use dmy dates from June 2022

- Use British English from February 2013

- Articles without Wikidata item

- Biography with signature

- Articles with hCards

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2022

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Find a Grave template with ID not in Wikidata

- AC with 0 elements

- 1869 births

- 1954 deaths

- 19th-century English writers

- 20th-century English writers

- Alumni of The Queen's College, Oxford

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- British vegetarianism activists

- Burials in Japan

- Denaturalized citizens of the United Kingdom

- English barristers

- English expatriates in Japan

- English feminist writers

- English pacifists

- English science fiction writers

- International law scholars

- LGBT writers from England

- Non-binary writers

- Organization founders

- People associated with the Vegetarian Society

- People from Cumberland

- Pseudonymous writers

- Radical feminists

- Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 2nd class

- Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 3rd class

- Transgender academics

- LGBT lawyers

- Transgender writers

- Transgender non-binary people

- Transgender rights activists

- Asexual non-binary people