The Eternal Feminine (Cézanne)

| The Eternal Feminine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Paul Cézanne |

| Year | 1864 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles |

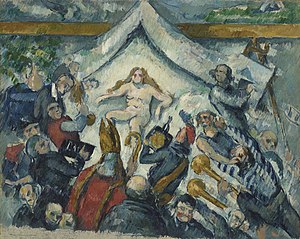

The Eternal Feminine is an 1877 oil on canvas painting by the French Post-Impressionist artist Paul Cézanne.[1] This is a rather ambiguous work where men of many professions and an artist (reportedly a depiction of Eugène Delacroix) who is painting this very picture are gathered around a single female figure. Here a whole range of professions, occupations and arts are represented: writers, lawyers, and a painter, possibly Delacroix, while others believe is Cézanne himself. The painter's representation of himself is lacking a mouth. The manifestation of the feminine is reclined upon a canopied bed outdoors.

The painting is in the permanent collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.[2]

Background

Cézanne became one of the first artists of his generation to successfully break away from impressionism and his work became an important stepping stone to art of the 20th century. This painting is as a post-impressionist painting as it is key in creating bridges between 19th and 20th century art through the stylistic approach he took. This painting could have been inspired by a picture Cézanne had previously seen in both Christian and Pagan art history surrounding the theme of adoring defied women. [3]

Introduction of New Techniques

This piece of art can be viewed as an end to the Romantic and Baroque works of Cézanne's early career through an introduction of new techniques regarding brush strokes. The structure and rhythm of the painting are shaped via parallel brush strokes that converge towards the central nude figure which created a new element of desirability to the woman. These strokes were also employed to unify the painting an impose an idea of order. [4]The Eternal Feminine was one of the first paintings where Cézanne used these consecutive strokes. This began to be the most prevalent strokes he used in his work. He began to employ this technique in future works and inspired younger artists, like Paul Signac and Gauguin, to employ this style of painting as well. [4] [5] This introduction of new techniques facilitated a transformation to something more commonly seen in museums. [4]This overall was a pivotal piece of art in the 19th century.

The Woman Depicted

There is a naked, golden-haired women placed on a generous bed depicted in this painting. The setting seems to be of a bedroom with a backdrop of a town or city with foliage beyond it. There is a vase of flowers to her right, a typical object that could be seen at a woman's bedside. The woman's body is on very public display as she has attracted an excited crowd through the use of her body as a spectacle. She appears to have an innocuous presentation with a blank face as she appears to be blinded with her eyeballs clotted. Despite being displayed as unprovocative, she still is painted with flowing blonde hair that displayed beauty. This woman is vulnerable in nature due to her openness. [3]

This painting displays much information about the role of the woman in political and symbolic order. The woman is compared to the Virgin Mary, a saint, or Venus in the way that it refers back to a familiar topic of Pagan and Christian history: adoring a defied women on an elevated surface. [3] He was able to emphasize on these ideas through exploiting the popular culture during this time period, referencing back to the topic of populism. [6] This is an approach that appeals to the greater public with more disregard to rules and the elite. The concept of free interpretation of the female body was heavily focused on in the creation of this work of art. Women were seen as sign and as body, and as national symbols and historical protagonists. [6]Cézanne made this concept the central idea of this painting.

Nudity is a central theme throughout Cézanne's work. The woman's pose is very unclear, as she could be either accepting the attention she is receiving or feels trapped. Facelessness is another common theme that Cézanne employs in his work, which he does in this painting with the woman as well. [7]

There is also a canopy portrayed over the woman's head that relates to a halo, also known as a mandoria. This is similar to the one surrounding Saint Anthony's temptress. [8]The halo is the shape of a diamond which creates a dramatic burst effect around the naked women. It is thought to represent Liberty in Liberty Leading the People, an oil painting done in 1830.[8]

Delacroix's Significance

Cézanne did not have many favorable feeling about Delacroix. Signs of this discomfort he likely experienced in their relationship began at the young age of 24. Cézanne made many efforts to measure up to Delacroix's master-like works, but these efforts appeared to be inadequate and weak. Cézanne's adoration for him became almost humiliating. [3]

Delacroix is interpreted to be one of the men surrounding the woman in the Eternal Feminine as well. It has also been suggested by the curator of the 2016 National Gallery exhibition "Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art", Christopher Riopelle that the work takes on the geometric configuration of The Death of Sardanapalus (1827) by Eugène Delacroix in reverse and it is as if it was created in response to the earlier work. The French art historian and curator Françoise Cachin proposed that the origin of this work lays in the earlier Delacroix.[9][10]

References

- ^ "The Eternal Feminine — Google Arts & Culture". Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ "The Eternal Feminine (L'Éternel Féminin) (Getty Museum)". Getty.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Wayne (2005). Cezanne and the Eternal Feminine. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 052183726X.

- ^ a b c Cachin, Francoise (1996). Cezanne. Philadelphia Museum of Art. ISBN 0876331002.

- ^ "The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection". The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Retrieved 2022-11-02.

- ^ a b "Cezanne, l'année terrible and the Eternal Feminin". Société Cezanne (in French). 2013-12-17. Retrieved 2022-11-02.

- ^ "The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection". The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Retrieved 2022-11-02.

- ^ a b Cézanne, Paul (2011). Cézanne and Paris. Denis Coutagne, Musée national du Luxembourg, Musée du Petit Palais, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Réunion des musées nationaux. Paris: Éditions de la RMN-Grand Palais. ISBN 978-2-7118-5919-1. OCLC 767535014.

- ^ McEwan, Olivia (2016-05-04). "A Show About Delacroix's Influence Is Sorely Missing His Work". Hyperallergic.com. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Andersen, Wayne (1996). "Cézanne's the eternal feminine as the whore of Babylon". The European Legacy. 1 (6): 1949–1960. doi:10.1080/10848779608579648.