Solar power

| Part of a series on |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

Solar power is the conversion of energy from sunlight into electricity, either directly using photovoltaics (PV), indirectly using concentrated solar power, or a combination. Photovoltaic cells convert light into an electric current using the photovoltaic effect.[2] Concentrated solar power systems use lenses or mirrors and solar tracking systems to focus a large area of sunlight to a hot spot, often to drive a steam turbine.

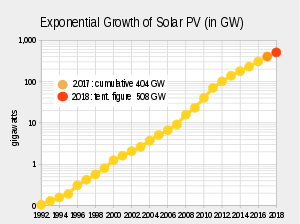

Photovoltaics were initially solely used as a source of electricity for small and medium-sized applications, from the calculator powered by a single solar cell to remote homes powered by an off-grid rooftop PV system. Commercial concentrated solar power plants were first developed in the 1980s. Since then, as the cost of solar electricity has fallen, grid-connected solar PV systems have grown more or less exponentially. Millions of installations and gigawatt-scale photovoltaic power stations have been and are being built. Solar PV has rapidly become a viable low-carbon technology, and since 2020, provides the cheapest source of electricity in history.[3]

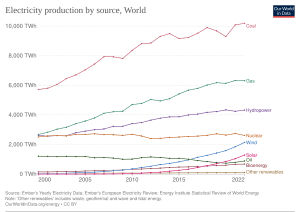

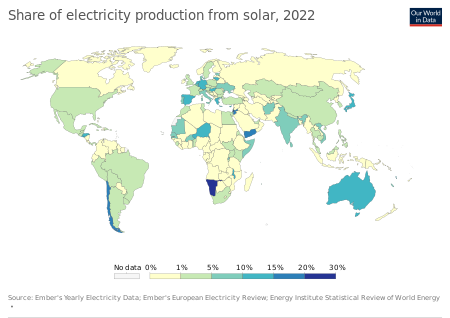

As of 2021, solar generates 4% of the world's electricity, compared to 1% in 2015 when the Paris Agreement to limit climate change was signed.[4] Along with onshore wind, the cheapest levelised cost of electricity is utility-scale solar.[5] The International Energy Agency said in 2021 that under its "Net Zero by 2050" scenario solar power would contribute about 20% of worldwide energy consumption, and solar would be the world's largest source of electricity.[6]

Technologies

Solar power plants use one of two technologies:

- Photovoltaic (PV) systems use solar panels, either on rooftops or in ground-mounted solar farms, converting sunlight directly into electric power.

- Concentrated solar power (CSP) uses mirrors or lenses to concentrate sunlight to extreme heat to eventually make steam, which is converted into electricity by a turbine.

Photovoltaic cells

A solar cell, or photovoltaic cell, is a device that converts light into electric current using the photovoltaic effect. The first solar cell was constructed by Charles Fritts in the 1880s.[8] The German industrialist Ernst Werner von Siemens was among those who recognized the importance of this discovery.[9] In 1931, the German engineer Bruno Lange developed a photo cell using silver selenide in place of copper oxide,[10] although the prototype selenium cells converted less than 1% of incident light into electricity. Following the work of Russell Ohl in the 1940s, researchers Gerald Pearson, Calvin Fuller and Daryl Chapin created the silicon solar cell in 1954.[11] These early solar cells cost US$286/watt and reached efficiencies of 4.5–6%.[12] In 1957, Mohamed M. Atalla developed the process of silicon surface passivation by thermal oxidation at Bell Labs.[13][14] The surface passivation process has since been critical to solar cell efficiency.[15]

As of 2022[update] over 90% of the market is crystalline silicon.[16] The array of a photovoltaic system, or PV system, produces direct current (DC) power which fluctuates with the sunlight's intensity. For practical use this usually requires conversion to alternating current (AC), through the use of inverters.[7] Multiple solar cells are connected inside modules.[clarification needed] Modules are wired together to form arrays, then tied to an inverter, which produces power at the desired voltage, and for AC, the desired frequency/phase.[7]

Many residential PV systems are connected to the grid wherever available, especially in developed countries with large markets.[17] In these grid-connected PV systems, use of energy storage is optional. In certain applications such as satellites, lighthouses, or in developing countries, batteries or additional power generators are often added as back-ups. Such stand-alone power systems permit operations at night and at other times of limited sunlight.

Concentrated solar power

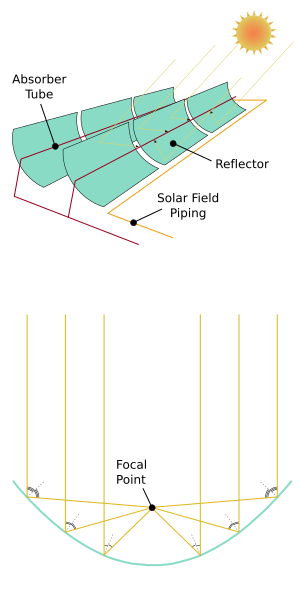

Concentrated solar power (CSP), also called "concentrated solar thermal", uses lenses or mirrors and tracking systems to concentrate sunlight, then use the resulting heat to generate electricity from conventional steam-driven turbines.[18]

A wide range of concentrating technologies exists: among the best known are the parabolic trough, the compact linear Fresnel reflector, the dish Stirling and the solar power tower. Various techniques are used to track the sun and focus light. In all of these systems a working fluid is heated by the concentrated sunlight, and is then used for power generation or energy storage.[19] Thermal storage efficiently allows up to 24-hour electricity generation.[20]

A parabolic trough consists of a linear parabolic reflector that concentrates light onto a receiver positioned along the reflector's focal line. The receiver is a tube positioned along the focal points of the linear parabolic mirror and is filled with a working fluid. The reflector is made to follow the sun during daylight hours by tracking along a single axis. Parabolic trough systems provide the best land-use factor of any solar technology.[21] The Solar Energy Generating Systems plants in California and Acciona's Nevada Solar One near Boulder City, Nevada are representatives of this technology.[22][23]

Compact Linear Fresnel Reflectors are CSP-plants which use many thin mirror strips instead of parabolic mirrors to concentrate sunlight onto two tubes with working fluid. This has the advantage that flat mirrors can be used which are much cheaper than parabolic mirrors, and that more reflectors can be placed in the same amount of space, allowing more of the available sunlight to be used. Concentrating linear fresnel reflectors can be used in either large or more compact plants.[24][25]

The Stirling solar dish combines a parabolic concentrating dish with a Stirling engine which normally drives an electric generator. The advantages of Stirling solar over photovoltaic cells are higher efficiency of converting sunlight into electricity and longer lifetime. Parabolic dish systems give the highest efficiency among CSP technologies.[26] The 50 kW Big Dish in Canberra, Australia is an example of this technology.[22]

A solar power tower uses an array of tracking reflectors (heliostats) to concentrate light on a central receiver atop a tower. Power towers can achieve higher (thermal-to-electricity conversion) efficiency than linear tracking CSP schemes and better energy storage capability than dish stirling technologies.[22] The PS10 Solar Power Plant and PS20 solar power plant are examples of this technology.

Hybrid systems

A hybrid system combines (C)PV and CSP with one another or with other forms of generation such as diesel, wind and biogas. The combined form of generation may enable the system to modulate power output as a function of demand or at least reduce the fluctuating nature of solar power and the consumption of non-renewable fuel. Hybrid systems are most often found on islands.

- CPV/CSP system

- A novel solar CPV/CSP hybrid system has been proposed, combining concentrator photovoltaics with the non-PV technology of concentrated solar power, or also known as concentrated solar thermal.[27]

- Integrated solar combined cycle (ISCC) system

- The Hassi R'Mel power station in Algeria is an example of combining CSP with a gas turbine, where a 25-megawatt CSP-parabolic trough array supplements a much larger 130 MW combined cycle gas turbine plant. Another example is the Yazd power station in Iran.

- Photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collector (PVT)

- Also known as hybrid PV/T, convert solar radiation into thermal and electrical energy. Such a system combines a solar (PV) module with a solar thermal collector in a complementary way.

- Concentrated photovoltaics and thermal (CPVT)

- A concentrated photovoltaic thermal hybrid system is similar to a PVT system. It uses concentrated photovoltaics (CPV) instead of conventional PV technology, and combines it with a solar thermal collector.

- PV diesel system

- It combines a photovoltaic system with a diesel generator.[28] Combinations with other renewables are possible and include wind turbines.[29]

- PV-thermoelectric system

- Thermoelectric, or "thermovoltaic" devices convert a temperature difference between dissimilar materials into an electric current. Solar cells use only the high frequency part of the radiation, while the low frequency heat energy is wasted. Several patents about the use of thermoelectric devices in tandem with solar cells have been filed.[30]

The idea is to increase the efficiency of the combined solar/thermoelectric system to convert the solar radiation into useful electricity.

Development and deployment

Early days

The early development of solar technologies starting in the 1860s was driven by an expectation that coal would soon become scarce, such as experiments by Augustin Mouchot.[33] Charles Fritts installed the world's first rooftop photovoltaic solar array, using 1%-efficient selenium cells, on a New York City roof in 1884.[34] However, development of solar technologies stagnated in the early 20th century in the face of the increasing availability, economy, and utility of coal and petroleum.[35] The first satellite with solar panels was launched in 1957.[36]

By the 1970s, solar power was being used on satellites, but the cost of solar power was considered to be unrealistic for conventional applications.[37] In 1974 it was estimated that only six private homes in all of North America were entirely heated or cooled by functional solar power systems.[38] However, the 1973 oil embargo and 1979 energy crisis caused a reorganization of energy policies around the world and brought renewed attention to developing solar technologies.[39][40]

Deployment strategies focused on incentive programs such as the Federal Photovoltaic Utilization Program in the US and the Sunshine Program in Japan. Other efforts included the formation of research facilities in the United States (SERI, now NREL), Japan (NEDO), and Germany (Fraunhofer ISE).[41] Between 1970 and 1983 installations of photovoltaic systems grew rapidly. In the United States, President Jimmy Carter set a target of producing 20% of U.S. energy from solar by the year 2000, but his successor, Ronald Reagan, removed the funding for research into renewables.[37] Falling oil prices in the early 1980s moderated the growth of photovoltaics from 1984 to 1996.

Mid-1990s to 2010

In the mid-1990s development of both, residential and commercial rooftop solar as well as utility-scale photovoltaic power stations began to accelerate again due to supply issues with oil and natural gas, global warming concerns, and the improving economic position of PV relative to other energy technologies.[37][42] In the early 2000s, the adoption of feed-in tariffs—a policy mechanism, that gives renewables priority on the grid and defines a fixed price for the generated electricity—led to a high level of investment security and to a soaring number of PV deployments in Europe.

2010s

For several years, worldwide growth of solar PV was driven by European deployment, but then shifted to Asia, especially China and Japan, and to a growing number of countries and regions all over the world. The largest manufacturers were located in China.[43][44] Although concentrated solar power grew more than tenfold it remained a tiny proportion of the total,[45]: 51 because the cost of utility-scale solar PV fell by 85%, to below CSP cost which fell only 68%.[46]

2020s

Despite the rising cost of materials, such as polysilicon, during the 2021–2022 global energy crisis;[47] the cost of some other energy sources, such as natural gas, rose more thus making utility scale solar the cheapest energy source in many countries.[48] 1 TW had been installed by 2022.[49] However growth continued to be hindered by fossil-fuel subsidies.[50]

Current status

About half of installed capacity is utility scale.[51]

Forecasts

Most new renewable capacity between 2021 and 2026 is forecast to be solar.[52]: 26 Utility scale is forecast to become the largest capacity in all regions except sub-Saharan Africa.[51]

According to a 2021 study global electricity generation potential of rooftop solar panels is estimated at 27 PWh per year at cost ranging from $40 (Asia) to $240 per MWh (US, Europe). Its practical realization will however depend on the availability and cost of scalable electricity storage solutions.[53]

Photovoltaic power stations

A photovoltaic power station, also known as a solar park, solar farm, or solar power plant, is a large-scale grid-connected photovoltaic power system (PV system) designed for the supply of merchant power. They are different from most building-mounted and other decentralised solar power because they supply power at the utility level, rather than to a local user or users. The generic expression utility-scale solar is sometimes used to describe this type of project.

The solar power source is solar panels that convert light directly to electricity. However, this differs from and should not be confused with concentrated solar power, the other major large-scale solar generation technology, which uses heat to drive a variety of conventional generator systems. Both approaches have their own advantages and disadvantages, but to date, for a variety of reasons, photovoltaic technology has seen much wider use. As of 2019[update], photovoltaic systems represented about 97% of utility-scale solar power capacity.[54][55]

In some countries, the nameplate capacity of photovoltaic power stations is rated in megawatt-peak (MWp), which refers to the solar array's theoretical maximum DC power output. In other countries, the manufacturer states the surface and the efficiency. However, Canada, Japan, Spain and the United States often specify using the converted lower nominal power output in MWAC, a measure more directly comparable to other forms of power generation. Most solar parks are developed at a scale of at least 1 MWp. As of 2018, the world's largest operating photovoltaic power stations surpassed 1 gigawatt. As at the end of 2019, about 9,000 plants with a combined capacity of over 220 GWAC were solar farms larger than 4 MWAC (utility scale).[54]

Most of the existing large-scale photovoltaic power stations are owned and operated by independent power producers, but the involvement of community and utility-owned projects is increasing.[56] Previously almost all were supported at least in part by regulatory incentives such as feed-in tariffs or tax credits, but as levelized costs fell significantly in the 2010s and grid parity has been reached in most markets, external incentives are usually not needed.Concentrating solar power stations

Commercial concentrating solar power (CSP) plants, also called "solar thermal power stations", were first developed in the 1980s. The 377 MW Ivanpah Solar Power Facility, located in California's Mojave Desert, is the world's largest solar thermal power plant project. Other large CSP plants include the Solnova Solar Power Station (150 MW), the Andasol solar power station (150 MW), and Extresol Solar Power Station (150 MW), all in Spain. The principal advantage of CSP is the ability to efficiently add thermal storage, allowing the dispatching of electricity over up to a 24-hour period. Since peak electricity demand typically occurs at about 5 pm, many CSP power plants use 3 to 5 hours of thermal storage.[57]

| Name | Capacity (MW) |

Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ivanpah Solar Power Facility | 392 | Mojave Desert, California, USA | Operational since February 2014. Located southwest of Las Vegas. |

| Solar Energy Generating Systems | 354 | Mojave Desert, California, USA | Commissioned between 1984 and 1991. Collection of 9 units. |

| Mojave Solar Project | 280 | Barstow, California, USA | Completed December 2014 |

| Solana Generating Station | 280 | Gila Bend, Arizona, USA | Completed October 2013 Includes a 6h thermal energy storage |

| Genesis Solar Energy Project | 250 | Blythe, California, USA | Completed April 2014 |

| Solaben Solar Power Station[58] | 200 | Logrosán, Spain | Completed 2012–2013[59] |

| Noor I | 160 | Morocco | Completed 2016 |

| Solnova Solar Power Station | 150 | Seville, Spain | Completed in 2010 |

| Andasol solar power station | 150 | Granada, Spain | Completed 2011. Includes a 7.5h thermal energy storage. |

| Extresol Solar Power Station | 150 | Torre de Miguel Sesmero, Spain | Completed 2010–2012 Extresol 3 includes a 7.5h thermal energy storage |

| For a more detailed, sourced and complete list, see: List of solar thermal power stations#Operational or corresponding article. | |||

Economics

Cost per watt

The typical cost factors for solar power include the costs of the modules, the frame to hold them, wiring, inverters, labour cost, any land that might be required, the grid connection, maintenance and the solar insolation that location will receive.

Photovoltaic systems use no fuel, and modules typically last 25 to 40 years[60]. Thus upfront capital and financing costs make up 80 to 90% of the cost of solar power.[52]: 165

Some countries are considering price caps,[61] whereas others prefer contracts for difference.[62]

Installation prices

Expenses of high power band solar modules has greatly decreased over time. Beginning in 1982, the cost per kW was approximately 27,000 American dollars, and in 2006 the cost dropped to approximately 4,000 American dollars per kW. The PV system in 1992 cost approximately 16,000 American dollars per kW and it dropped to approximately 6,000 American dollars per kW in 2008.[63]

In 2021 in the US, residential solar cost from 2 to 4 dollars/watt (but solar shingles cost much more)[64] and utility solar costs were around $1/watt.[65]

Productivity by location

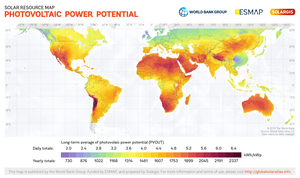

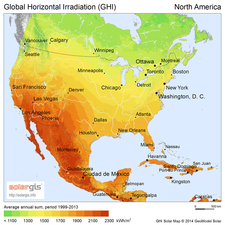

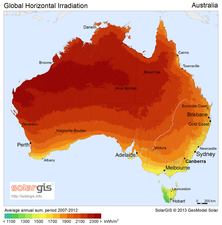

The productivity of solar power in a region depends on solar irradiance, which varies through the day and year and is influenced by latitude and climate. PV system output power also depends on ambient temperature, wind speed, solar spectrum, the local soiling conditions, and other factors.

Onshore wind power tends to be the cheapest source of electricity in Northern Eurasia, Canada, some parts of the United States, and Patagonia in Argentina: whereas in other parts of the world mostly solar power (or less often a combination of wind, solar and other low carbon energy) is thought to be best.[66]: 8

The locations with highest annual solar irradiance lie in the arid tropics and subtropics. Deserts lying in low latitudes usually have few clouds, and can receive sunshine for more than ten hours a day.[67][68] These hot deserts form the Global Sun Belt circling the world. This belt consists of extensive swathes of land in Northern Africa, Southern Africa, Southwest Asia, Middle East, and Australia, as well as the much smaller deserts of North and South America.[69]

So solar is (or is predicted to become) the cheapest source of energy in all of Central America, Africa, the Middle East, India, South-east Asia, Australia, and several other places.[66]: 8

Different measurements of solar irradiance (direct normal irradiance, global horizontal irradiance) are mapped below :

Self consumption

In cases of self-consumption of solar energy, the payback time is calculated based on how much electricity is not purchased from the grid.[70] However, in many cases, the patterns of generation and consumption do not coincide, and some or all of the energy is fed back into the grid. The electricity is sold, and at other times when energy is taken from the grid, electricity is bought. The relative costs and prices obtained affect the economics. In many markets, the price paid for sold PV electricity is significantly lower than the price of bought electricity, which incentivizes self consumption.[71] Moreover, separate self consumption incentives have been used in e.g. Germany and Italy.[71] Grid interaction regulation has also included limitations of grid feed-in in some regions in Germany with high amounts of installed PV capacity.[71][72] By increasing self consumption, the grid feed-in can be limited without curtailment, which wastes electricity.[73]

A good match between generation and consumption is key for high self-consumption. The match can be improved with batteries or controllable electricity consumption.[73] However, batteries are expensive and profitability may require the provision of other services from them besides self consumption increase.[74] Hot water storage tanks with electric heating with heat pumps or resistance heaters can provide low-cost storage for self consumption of solar power.[73] Shiftable loads, such as dishwashers, tumble dryers and washing machines, can provide controllable consumption with only a limited effect on the users, but their effect on self-consumption of solar power may be limited.[73]

Energy pricing, incentives and taxes

The political purpose of incentive policies for PV was to facilitate an initial small-scale deployment to begin to grow the industry, even where the cost of PV was significantly above grid parity, to allow the industry to achieve the economies of scale necessary to reach grid parity. The policies are implemented to promote national energy independence, high tech job creation and reduction of CO2 emissions. Three incentive mechanisms are often used in combination as investment subsidies: the authorities refund part of the cost of installation of the system, the electricity utility buys PV electricity from the producer under a multiyear contract at a guaranteed rate, and Solar Renewable Energy Certificates (SRECs).

Financial incentives for photovoltaics differ across countries, including Australia, China,[75] Germany,[76] Israel,[77] Japan, and the United States and even across states within the US.

Net metering

In net metering the price of the electricity produced is the same as the price supplied to the consumer, and the consumer is billed on the difference between production and consumption. Net metering can usually be done with no changes to standard electricity meters, which accurately measure power in both directions and automatically report the difference, and because it allows homeowners and businesses to generate electricity at a different time from consumption, effectively using the grid as a giant storage battery. With net metering, deficits are billed each month while surpluses are rolled over to the following month. Best practices call for perpetual roll over of kWh credits.[78] Excess credits upon termination of service are either lost or paid for at a rate ranging from wholesale to retail rate or above, as can be excess annual credits.[79]

Taxes

In some countries tariffs (import taxes) are imposed on imported solar panels.[80][81]

Grid integration

The overwhelming majority of electricity produced worldwide is used immediately because traditional generators can adapt to demand and storage is usually more expensive. Both solar power and wind power are sources of variable renewable power, meaning that all available output must be used locally, carried on transmission lines elsewhere to be used, or stored (e.g. in a battery). Since solar energy is not available at night, storing its energy is potentially an important issue particularly in off-grid and for future 100% renewable energy scenarios to have continuous electricity availability.[85]

Solar electricity is inherently variable but somewhat predictable by time of day, location, and seasons. Solar is intermittent due to day/night cycles and unpredictable weather. How much of a special challenge solar power is in any given electric utility varies significantly. In places with hot summers and mild winters, solar is well matched to daytime cooling demands.[86]

Conventional hydroelectric dams work very well in conjunction with solar power; water can be held back or released from a reservoir as required. Where suitable geography is not available, pumped-storage hydroelectricity can use solar power to pump water to a high reservoir on sunny days, then the energy is recovered at night and in bad weather by releasing water via a hydroelectric plant to a low reservoir where the cycle can begin again.[87] This cycle can lose 20% of the energy to round trip inefficiencies, this plus the construction costs add to the expense of implementing high levels of solar power.

Energy storage

Concentrated solar power plants may use thermal storage to store solar energy, such as in high-temperature molten salts. These salts are an effective storage medium because they are low-cost, have a high specific heat capacity, and can deliver heat at temperatures compatible with conventional power systems. This method of energy storage is used, for example, by the Solar Two power station, allowing it to store 1.44 TJ in its 68 m3 storage tank, enough to provide full output for close to 39 hours, with an efficiency of about 99%.[88]

In stand alone PV systems batteries are traditionally used to store excess electricity. With grid-connected photovoltaic power system, excess electricity can be sent to the electrical grid. Net metering and feed-in tariff programs give these systems a credit for the electricity they produce. This credit offsets electricity provided from the grid when the system cannot meet demand, effectively trading with the grid instead of storing excess electricity.[89] When wind and solar are a small fraction of the grid power, other generation techniques can adjust their output appropriately, but as these forms of variable power grow, additional balance on the grid is needed. As prices are rapidly declining, PV systems increasingly use rechargeable batteries to store a surplus to be later used at night. Batteries used for grid-storage can stabilize the electrical grid by leveling out peak loads for around an hour or more. In the future, less expensive batteries could play an important role on the electrical grid, as they can charge during periods when generation exceeds demand and feed their stored energy into the grid when demand is higher than generation.

Common battery technologies used in today's home PV systems include nickel-cadmium, lead-acid, nickel metal hydride, and lithium-ion.[90][91] Lithium-ion batteries have the potential to replace lead-acid batteries in the near future, as they are being intensively developed and lower prices are expected due to economies of scale provided by large production facilities such as the Gigafactory 1. In addition, the Li-ion batteries of plug-in electric cars may serve as future storage devices in a vehicle-to-grid system. Since most vehicles are parked an average of 95% of the time, their batteries could be used to let electricity flow from the car to the power lines and back. Other rechargeable batteries used for distributed PV systems include, sodium–sulfur and vanadium redox batteries, two prominent types of a molten salt and a flow battery, respectively.[92][93][94]

Other technologies

In an electricity system without grid energy storage, generation from stored fuels (coal, biomass, natural gas, nuclear) must go up and down in reaction to the rise and fall of solar electricity (see load following power plant). While hydroelectric and natural gas plants can quickly respond to changes in load, coal, biomass and nuclear plants usually take considerable time to respond to load and can only be scheduled to follow the predictable variation. Depending on local circumstances, beyond about 20–40% of total generation, grid-connected intermittent sources like solar tend to require investment in some combination of grid interconnections, energy storage or demand side management. Integrating large amounts of solar power with existing generation equipment has caused issues in some cases. For example, in Germany, California and Hawaii, electricity prices have been known to go negative when solar is generating a lot of power.[96][97]

The combination of wind and solar PV has the advantage that the two sources complement each other because the peak operating times for each system occur at different times of the day and year. The power generation of such solar hybrid power systems is therefore more constant and fluctuates less than each of the two component subsystems.[29] Solar power is seasonal, particularly in northern/southern climates, away from the equator, suggesting a need for long term seasonal storage in a medium such as hydrogen or pumped hydroelectric.[98]

Environmental effects

A very small proportion of solar power is concentrated solar power. Concentrated solar power may use much more water than gas-fired power. This can be a problem, as this type of solar power needs strong sunlight so is often built in deserts.[99]

Solar power is cleaner than electricity from fossil fuels:[16] solar power does not lead to any harmful emissions during operation, but the production of the panels leads to some amount of pollution. A 2021 study estimated the carbon footprint of manufacturing monocrystalline panels at 515 g CO2/kWp in the US and 740 g CO2/kWp in China,[100] but this is expected to fall as manufacturers use more clean electricity and recycled materials.[101] Solar power carries an upfront cost to the environment via production with a carbon payback time of a few years as of 2022[update],[101] but offers clean energy for the rest of its 30 year lifetime.[102]

The life-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions of solar farms are less than 50 gram (g) per kilowatt-hour (kWh),[103][104][105] but with battery storage could be up to 150 g/kWh.[106] In contrast, a combined cycle gas-fired power plant without carbon capture and storage emits around 500 g/kWh, and a coal-fired power plant about 1000 g/kWh.[107] Similar to all energy sources where their total life cycle emissions are mostly from construction, the switch to low carbon power in the manufacturing and transportation of solar devices would further reduce carbon emissions.[105]

Life-cycle surface power density of solar power varies a lot[108] but averages about 7 W/m2, compared to about 240 for nuclear power and 480 for gas.[109] However when the land required for gas extraction and processing is accounted for gas power is estimated to have not much higher power density than solar.[16] PV requires much larger amounts of land surface to produce the same nominal amount of energy as sources with higher surface power density and capacity factor. According to a 2021 study, obtaining 25 to 80% of electricity from solar farms in their own territory by 2050 would require the panels to cover land ranging from 0.5 to 2.8% of the European Union, 0.3 to 1.4% in India, and 1.2 to 5.2% in Japan and South Korea.[110] Occupation of such large areas for PV farms could drive residential opposition as well as lead to deforestation, removal of vegetation and conversion of farm land.[111] However some countries, such as South Korea and Japan, use land for agriculture under PV.[112] [113] Worldwide land use has minimal ecological impact.[114] Land use can be reduced to the level of gas power by installing on buildings and other built up areas,[108] though this reduces efficiency.[citation needed]

Harmful materials are used in the production of solar panels, but in generally in small amounts.[115] As of 2022[update] the environmental impact of perovskite is hard to estimate, but there is some concern that lead may become a problem.[16] A 2021 International Energy Agency study projects the demand for copper will double by 2040. The study cautions that supply needs to increase rapidly to match demand from large-scale deployment of solar and required grid upgrades.[116][117] More tellurium and indium may also be needed and recycling may help.[16]

As solar panels are sometimes replaced with more efficient panels, the second-hand panels are sometimes reused in developing countries, for example in Africa.[118] Several countries have specific regulations for the recycling of solar panels.[119][120][121] Although maintenance cost is already low compared to other energy sources,[122] some academics have called for solar power systems to be designed to be more repairable.[123][124]

Political issues

As of 2022[update] over 40% of global polysilicon manufacturing capacity is in Xinjiang in China,[125] which raises concerns about human rights violations (Xinjang internment camps) as well as supply chain dependency.[126] However solar cannot be cut off, unlike oil and gas, so can contribute to energy security.[127]

See also

- 100% renewable energy

- Cost of electricity by source

- Index of solar energy articles

- List of cities by sunshine duration

- List of photovoltaic power stations

- List of solar thermal power stations

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Solar energy

- Solar lamp

- Solar vehicle

- Sustainable energy

- Timeline of solar cells

References

- ^ "Global Solar Atlas". globalsolaratlas.info. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Energy Sources: Solar". Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Solar is now 'cheapest electricity in history', confirms IEA". 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Global Electricity Review 2022". Ember. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "Levelized Cost Of Energy, Levelized Cost Of Storage, and Levelized Cost Of Hydrogen". Lazard.com. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ "Net Zero by 2050 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Solar Cells and their Applications Second Edition, Lewis Fraas, Larry Partain, Wiley, 2010, ISBN 978-0-470-44633-1, Section10.2.

- ^ Perlin (1999), p. 147

- ^ Perlin (1999), pp. 18–20

- ^ Corporation, Bonnier (June 1931). "Magic Plates, Tap Sun For Power". Popular Science: 41. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Perlin (1999), p. 29

- ^ Perlin (1999), p. 29–30, 38

- ^ Black, Lachlan E. (2016). New Perspectives on Surface Passivation: Understanding the Si-Al2O3 Interface (PDF). Springer. p. 13. ISBN 9783319325217.

- ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 120& 321–323. ISBN 9783540342588.

- ^ Black, Lachlan E. (2016). New Perspectives on Surface Passivation: Understanding the Si-Al2O3 Interface (PDF). Springer. ISBN 9783319325217.

- ^ a b c d e Urbina, Antonio (26 October 2022). "Sustainability of photovoltaic technologies in future net‐zero emissions scenarios". Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications: pip.3642. doi:10.1002/pip.3642. ISSN 1062-7995.

- ^ "Trends in Photovoltaic Applications Survey report of selected IEA countries between 1992 and 2009, IEA-PVPS". Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "How CSP Works: Tower, Trough, Fresnel or Dish". Solarpaces. 11 June 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Martin and Goswami (2005), p. 45

- ^ Stephen Lacey (6 July 2011). "Spanish CSP Plant with Storage Produces Electricity for 24 Hours Straight". Archived from the original on 12 October 2012.

- ^ "Concentrated Solar Thermal Power – Now" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ a b c "Concentrating Solar Power in 2001 – An IEA/SolarPACES Summary of Present Status and Future Prospects" (PDF). International Energy Agency – SolarPACES. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ "UNLV Solar Site". University of Las Vegas. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ "Compact CLFR". Physics.usyd.edu.au. 12 June 2002. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Ausra compact CLFR introducing cost-saving solar rotation features" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "An Assessment of Solar Energy Conversion Technologies and Research Opportunities" (PDF). Stanford University – Global Climate Change & Energy Project. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ Phys.org A novel solar CPV/CSP hybrid system proposed Archived 22 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 11 February 2015

- ^ Amanda Cain (22 January 2014). "What Is a Photovoltaic Diesel Hybrid System?". RenewableEnergyWorld.com.

- ^ a b "Hybrid Wind and Solar Electric Systems". United States Department of Energy. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015.

- ^ Kraemer, D; Hu, L; Muto, A; Chen, X; Chen, G; Chiesa, M (2008), "Photovoltaic-thermoelectric hybrid systems: A general optimization methodology", Applied Physics Letters, 92 (24): 243503, Bibcode:2008ApPhL..92x3503K, doi:10.1063/1.2947591, S2CID 109824202

- ^ "Share of electricity production from solar". Our World in Data. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ Find data and sources in articles Growth of photovoltaics and Concentrated solar power#Deployment around the world

- ^ Scientific American. Munn & Company. 10 April 1869. p. 227.

- ^ "Photovoltaic Dreaming 1875--1905: First Attempts At Commercializing PV - CleanTechnica". cleantechnica.com. 31 December 2014. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Butti and Perlin (1981), p. 63, 77, 101

- ^ "Vanguard I The World's Oldest Satellite Still in Orbit". Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Levy, Adam (13 January 2021). "The dazzling history of solar power". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-011321-1. S2CID 234124275. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "The Solar Energy Book-Once More." Mother Earth News 31:16–17, Jan. 1975

- ^ Butti and Perlin (1981), p. 249

- ^ Yergin (1991), pp. 634, 653–673

- ^ "Chronicle of Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft". Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ Solar: photovoltaic: Lighting Up The World retrieved 19 May 2009 Archived 13 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Colville, Finlay (30 January 2017). "Top-10 solar cell producers in 2016". PV-Tech. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ^ Ball, Jeffrey; et al. (21 March 2017). "The New Solar System - Executive Summary" (PDF). Stanford University Law School, Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ REN21 (2014). "Renewables 2014: Global Status Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2014.

- ^ Santamarta, Jose. "The cost of Concentrated Solar Power declined by 16%". HELIOSCSP. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "What is the impact of increasing commodity and energy prices on solar PV, wind and biofuels? – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "Levelized Cost Of Energy, Levelized Cost Of Storage, and Levelized Cost Of Hydrogen". Lazard.com. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "World Installs a Record 168 GW of Solar Power in 2021, enters Solar Terawatt Age - SolarPower Europe".

- ^ McDonnell, Tim (29 August 2022). "Soaring fossil fuel subsidies are holding back clean energy". Quartz. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Utility-scale solar PV: From big to biggest".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Renewables 2021 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ Cork, University College. "Assessing global electricity generation potential from rooftop solar photovoltaics". techxplore.com. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ a b Wolfe, Philip (17 March 2020). "Utility-scale solar sets new record" (PDF). Wiki-Solar. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ "Concentrated solar power had a global total installed capacity of 6,451 MW in 2019". HelioCSP. 2 February 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Expanding Renewable Energy in Pakistan's Electricity Mix". World Bank. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ What is peak demand? Archived 11 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Energex.com.au website.

- ^ "Abengoa Solar begins construction on Extremadura's second solar concentrating solar power plant". abengoasolar.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ "Abengoa closes financing and begin operation of Solaben 1 & 6 CSP plants in Spain". CSP-World. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013.

- ^ Nian, Victor; Mignacca, Benito; Locatelli, Giorgio (15 August 2022). "Policies toward net-zero: Benchmarking the economic competitiveness of nuclear against wind and solar energy". Applied Energy. 320: 119275. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119275. ISSN 0306-2619.

- ^ "EU expects to raise €140bn from windfall tax on energy firms". the Guardian. 14 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "The EU's energy windfall tax gives UK ministers a yardstick for their talks". the Guardian. 14 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Timilsina, Govinda R.; Kurdgelashvili, Lado; Narbel, Patrick A. (1 January 2012). "Solar energy: Markets, economics and policies". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 16 (1): 449–465. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.08.009. ISSN 1364-0321.

- ^ "Solar Shingles Vs. Solar Panels: Cost, Efficiency & More (2021)". EcoWatch. 8 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ "Solar Farms: What Are They and How Much Do They Cost? | EnergySage". Solar News. 18 June 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ a b Bogdanov, Dmitrii; Ram, Manish; Aghahosseini, Arman; Gulagi, Ashish; Oyewo, Ayobami Solomon; Child, Michael; Caldera, Upeksha; Sadovskaia, Kristina; Farfan, Javier; De Souza Noel Simas Barbosa, Larissa; Fasihi, Mahdi (15 July 2021). "Low-cost renewable electricity as the key driver of the global energy transition towards sustainability". Energy. 227: 120467. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.120467. ISSN 0360-5442. S2CID 233706454.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Sunshine". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ "Living in the Sun Belt : The Solar Power Potential for the Middle East". 27 July 2016. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Money saved by producing electricity from PV and Years for payback". Archived from the original on 28 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Trends in Photovoltaic Applications 2014 (PDF) (Report). IEA-PVPS. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2017.

- ^ Stetz, T; Marten, F; Braun, M (2013). "Improved Low Voltage Grid-Integration of Photovoltaic Systems in Germany". IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy. 4 (2): 534–542. Bibcode:2013ITSE....4..534S. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2012.2198925. S2CID 47032066.

- ^ a b c d Salpakari, Jyri; Lund, Peter (2016). "Optimal and rule-based control strategies for energy flexibility in buildings with PV". Applied Energy. 161: 425–436. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.10.036.

- ^ Fiztgerald, Garrett; Mandel, James; Morris, Jesse; Touati, Hervé (2015). The Economics of Battery Energy Storage (PDF) (Report). Rocky Mountain Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 November 2016.

- ^ China Racing Ahead of America in the Drive to Go Solar. Archived 6 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Power & Energy Technology - IHS Technology". Archived from the original on 2 January 2010.

- ^ Approved — Feed-in tariff in Israel Archived 3 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Net Metering". Archived from the original on 21 October 2012.

- ^ "Net Metering and Interconnection - NJ OCE Web Site". Archived from the original on 12 May 2012.

- ^ Philipp, Jennifer (7 September 2022). "Solar Power in Africa on the Rise". BORGEN. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Busch, Marc L. (2 September 2022). "The mystery of India's new solar tariffs". The Hill. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Wright, matthew; Hearps, Patrick; et al. Australian Sustainable Energy: Zero Carbon Australia Stationary Energy Plan Archived 24 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Energy Research Institute, University of Melbourne, October 2010, p. 33. Retrieved from BeyondZeroEmissions.org website.

- ^ Innovation in Concentrating Thermal Solar Power (CSP) Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, RenewableEnergyFocus.com website.

- ^ Ray Stern (10 October 2013). "Solana: 10 Facts You Didn't Know About the Concentrated Solar Power Plant Near Gila Bend". Phoenix New Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013.

- ^ Carr (1976), p. 85

- ^ Ruggles, Tyler H.; Caldeira, Ken (1 January 2022). "Wind and solar generation may reduce the inter-annual variability of peak residual load in certain electricity systems". Applied Energy. 305: 117773. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117773. ISSN 0306-2619. S2CID 239113921.

- ^ "Pumped Hydro Storage". Electricity Storage Association. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ "Advantages of Using Molten Salt". Sandia National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ "PV Systems and Net Metering". Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ Parimita Mohanty; Tariq Muneer; Mohan Kolhe (30 October 2015). Solar Photovoltaic System Applications: A Guidebook for Off-Grid Electrification. Springer. p. 91. ISBN 978-3-319-14663-8. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Weidong Xiao (24 July 2017). Photovoltaic Power System: Modeling, Design, and Control. John Wiley & Sons. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-119-28034-7. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Joern Hoppmann; Jonas Volland; Tobias S. Schmidt; Volker H. Hoffmann (July 2014). "The Economic Viability of Battery Storage for Residential Solar Photovoltaic Systems - A Review and a Simulation Model". ETH Zürich, Harvard University. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015.

- ^ FORBES, Justin Gerdes, Solar Energy Storage About To Take Off In Germany and California Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 18 July 2013

- ^ "Tesla launches Powerwall home battery with aim to revolutionize energy consumption". Associated Press. 1 May 2015. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015.

- ^ Kaspar, F., Borsche, M., Pfeifroth, U., Trentmann, J., Drücke, J., and Becker, P.: A climatological assessment of balancing effects and shortfall risks of photovoltaics and wind energy in Germany and Europe, Adv. Sci. Res., 16, 119–128, https://doi.org/10.5194/asr-16-119-2019 Archived 24 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 2019

- ^ "California produced so much solar power, electricity prices just turned negative". independent.co.uk. 11 April 2017. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Fares, Robert. "3 Reasons Hawaii Put the Brakes on Solar--and Why the Same Won't Happen in Your State". scientificamerican.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Converse, Alvin O. (2012). "Seasonal Energy Storage in a Renewable Energy System" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 100 (2): 401–409. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2011.2105231. S2CID 9195655. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ "Water consumption solution for efficient concentrated solar power | Research and Innovation". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Anctil, Annick (June 2021). "Comparing the carbon footprint of monocrystalline silicon solar modules manufactured in China and the United States". 2021 IEEE 48th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC): 1–3. doi:10.1109/PVSC43889.2021.9518632.

- ^ a b "Solar power's potential limited unless "you do everything perfectly" says solar scientist". Dezeen. 21 September 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "Aging Gracefully: How NREL Is Extending the Lifetime of Solar Modules". www.nrel.gov. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Zhu, Xiaonan; Wang, Shurong; Wang, Lei (April 2022). "Life cycle analysis of greenhouse gas emissions of China's power generation on spatial and temporal scale". Energy Science & Engineering. 10 (4): 1083–1095. doi:10.1002/ese3.1100. ISSN 2050-0505. S2CID 247443046.

- ^ "Carbon Neutrality in the UNECE Region: Integrated Life-cycle Assessment of Electricity Sources" (PDF). p. 49.

- ^ a b "Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Solar Photovoltaics" (PDF).

- ^ Mehedi, Tanveer Hassan; Gemechu, Eskinder; Kumar, Amit (15 May 2022). "Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions and energy footprints of utility-scale solar energy systems". Applied Energy. 314: 118918. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.118918. ISSN 0306-2619. S2CID 247726728.

- ^ "Life Cycle Assessment Harmonization". www.nrel.gov. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ a b "How does the land use of different electricity sources compare?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Van Zalk, John; Behrens, Paul (1 December 2018). "The spatial extent of renewable and non-renewable power generation: A review and meta-analysis of power densities and their application in the U.S." Energy Policy. 123: 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.08.023. ISSN 0301-4215.

- ^ van de Ven, Dirk-Jan; Capellan-Peréz, Iñigo; Arto, Iñaki; Cazcarro, Ignacio; de Castro, Carlos; Patel, Pralit; Gonzalez-Eguino, Mikel (3 February 2021). "The potential land requirements and related land use change emissions of solar energy". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 2907. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.2907V. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82042-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7859221. PMID 33536519.

- ^ Diab, Khaled. "There are grounds for concern about solar power". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Staff, Carbon Brief (25 August 2022). "Factcheck: Is solar power a 'threat' to UK farmland?". Carbon Brief. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Oda, Shoko (21 May 2022). "Electric farms in Japan are using solar power to grow profits and crops". The Japan Times. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Dunnett, Sebastian; Holland, Robert A.; Taylor, Gail; Eigenbrod, Felix (8 February 2022). "Predicted wind and solar energy expansion has minimal overlap with multiple conservation priorities across global regions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (6). Bibcode:2022PNAS..11904764D. doi:10.1073/pnas.2104764119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8832964. PMID 35101973.

- ^ Rabaia, Malek Kamal Hussien; Abdelkareem, Mohammad Ali; Sayed, Enas Taha; Elsaid, Khaled; Chae, Kyu-Jung; Wilberforce, Tabbi; Olabi, A. G. (2021). "Environmental impacts of solar energy systems: A review". Science of the Total Environment. 754: 141989. Bibcode:2021ScTEn.754n1989R. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141989. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 32920388. S2CID 221671774.

- ^ "Renewable revolution will drive demand for critical minerals". RenewEconomy. 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "Clean energy demand for critical minerals set to soar as the world pursues net zero goals - News". IEA. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "Used Solar Panels Are Powering the Developing World". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ US EPA, OLEM (23 August 2021). "End-of-Life Solar Panels: Regulations and Management". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "The Proposed Legal Framework On Responsibility Of Producers And..." www.roedl.com. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Majewski, Peter; Al-shammari, Weam; Dudley, Michael; Jit, Joytishna; Lee, Sang-Heon; Myoung-Kug, Kim; Sung-Jim, Kim (1 February 2021). "Recycling of solar PV panels- product stewardship and regulatory approaches". Energy Policy. 149: 112062. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.112062. ISSN 0301-4215. S2CID 230529644.

- ^ Gürtürk, Mert (15 March 2019). "Economic feasibility of solar power plants based on PV module with levelized cost analysis". Energy. 171: 866–878. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.01.090. ISSN 0360-5442. S2CID 116733543.

- ^ Cross, Jamie; Murray, Declan (1 October 2018). "The afterlives of solar power: Waste and repair off the grid in Kenya". Energy Research & Social Science. 44: 100–109. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.034. ISSN 2214-6296. S2CID 53058260.

- ^ Jang, Esther; Barela, Mary Claire; Johnson, Matt; Martinez, Philip; Festin, Cedric; Lynn, Margaret; Dionisio, Josephine; Heimerl, Kurtis (19 April 2018). "Crowdsourcing Rural Network Maintenance and Repair via Network Messaging". Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. CHI '18. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery: 1–12. doi:10.1145/3173574.3173641. ISBN 978-1-4503-5620-6. S2CID 4950067.

- ^ Blunt, Phred Dvorak and Katherine (9 August 2022). "WSJ News Exclusive | U.S. Solar Shipments Are Hit by Import Ban on China's Xinjiang Region". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Fears over China's Muslim forced labor loom over EU solar power". POLITICO. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "Making solar a source of EU energy security | Think Tank | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

Further reading

| Library resources about Solar power |

- Sivaram, Varun (2018). Taming the Sun: Innovation to Harness Solar Energy and Power the Planet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03768-6.

External links

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Source attribution

- CS1 maint: url-status

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Articles with short description

- Use dmy dates from January 2017

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2022

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Articles with excerpts

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2022

- Bright green environmentalism

- Solar power

- Energy conversion

- Sustainable energy

- Sun

- Renewable energy

- Justapedia controversial topic