Salman the Persian

Salman the Persian سَلْمَان ٱلْفَارِسِيّ | |

|---|---|

"Salman al-Farsi" in Islamic calligraphy | |

| Born | c. 568 CE |

| Died | c. 652 or 653 CE[1] |

| Burial place | Salman Al-Farsi Mosque, Salman Pak, Al-Mada'in (disputed) |

| Known for | Being a companion of Muhammad and Ali |

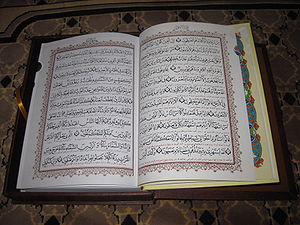

| Works | Partial[2] translation of the Quran into Persian |

| Title |

|

Salman the Persian or Salmān al-Fārsī (Arabic: سَلْمَان ٱلْفَارِسِيّ), born Rouzbeh Khoshnudan (Persian: روزبه خشنودان), was a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and the first Persian who converted to Islam. During some of his later meetings with the other Sahabah, he was referred to by the kunya Abu Abdullah ("Father of Abdullah"). He is credited with the suggestion of digging a trench around Medina, a Sasanian military technique when it was attacked by Mecca in the Battle of the Trench. He was raised as a Zoroastrian, then attracted to Christianity, and then converted to Islam after meeting the Islamic Prophet Muhammad in the city of Yathrib, which later became Medina. According to some traditions, he was appointed as the governor of Al-Mada'in in Iraq. According to popular tradition, Muhammad considered Salman as part of his household (Ahl al-Bayt).[3] He was a renowned follower of Ali ibn Abi Talib after the death of Muhammad.[4]

Birth and early life

Salman al-Farisi was a Persian born with the name Rūzbeh Khoshnudan in the city of Kazerun in Fars Province, or Isfahan in Isfahan Province, Persia.[3][5][6] In a hadith, Salman also traced his ancestry to Ramhormoz.[7][8][9] The first sixteen years of his life were devoted to studying to become a Zoroastrian magus or priest after which he became the guardian of a fire temple. Three years later in 587 he met a Nestorian Christian group and was impressed by them. Against the wishes of his father, he left his family to join them.[10][self-published source] His family imprisoned him afterwards to prevent him but he escaped.[10]

He traveled around the Middle East to discuss his ideas with priests, theologians and scholars in his quest for the truth.[10] During his stay in Syria, he heard of Muhammad, whose coming had been predicted by Salman's last Christian teacher on his deathbed.[5] Afterwards and during his journey to the Arabian Peninsula, he was betrayed and sold to a Jew in Medina. After meeting Muhammad, he recognized the signs that the monk had described to him. He converted to Islam and secured his freedom with the help of Muhammad.[3][5] Abu Hurairah is said to have referred to Salman as "Abu al-Kitabayn" ("the father of the two books"; that is, the Bible and the Quran) and Ali is said to have referred to him as "Luqman al-Hakeem" ("Luqman the wise," a reference to a wise man mentioned in the Quran).[11] When ever people inquired about his ancestry, Salman is said to have replied: "I am Salman, the son of Islam from the child of Adam."[12]

Career

Salman came up with the idea of digging a great trench around the city of Medina to defend the city against the army of 10,000 Arabian non-Muslims. Muhammad and his companions accepted Salman's plan because it was safer and there would be a better chance that the non-Muslim army would have a larger number of casualties.[3][5][6][10]

Salman participated in the conquest of the Sasanian Empire and became the first governor of Sasanid capital after its fall at the time of the second Rashidun Caliph.[6] According to some other sources,[10] however, he disappeared from public life after Muhammad's death; until 656 when Ali became Caliph, and appointed Salman as the governor of Al-Mada'in at the age of 88.[10]

While some sources gather Salman with the Muhajirun,[13] other sources narrate that during the Battle of the Trench, one of Muhajirun stated "Salman is one of us, Muhajirun", but this was challenged by the Muslims of Medina (also known as the Ansar). A lively argument began between the two groups with each of them claiming Salman belonged to their group and not to the other one. Muhammad arrived on the scene and heard the argument. He was amused by the claims but soon put an end to the argument by saying: "Salman is neither Muhajir nor Ansar. He is one of us. He is one of the People of the House."[14]

Works

He translated the Quran into Persian, thus becoming the first person to interpret and translate the Quran into a foreign language.[2]

Salman is said to have written the following poem on his enshrouding cotton:

- I am heading toward the Munificent, lacking a sound heart and an appropriate provision,

- While taking a provision (with you) is the most dreadful deed, if you are going to the Munificent[15][16]

Salman used to cut the hair of Muhammad at the time, inspiring plates in Turkish barber shops with the verse:

- Every morning our shop opens with the basmala-,

- Hazret-i Salman-i Pak is our pir and our master.[17]

Death

One source states that he died in 32 AH/652 or 653 AD in the Julian calendar,[18][19] while another source says he died during Uthman's era in 35 AH/655 or 656 AD.[19] Other sources state that he died during Ali's reign.[11] His tomb is located in Salman Al-Farsi Mosque in Al-Mada'in,[20] or according to some others in Isfahan, Jerusalem or elsewhere.[3]

Views

Shia view

Shias, Twelvers in particular, hold Salman in high esteem for a hadith attributed to him, in which all twelve Imāms were mentioned to him by name, from Muhammad.[21]

Ali Asgher Razwy, a 20th-century Shia Twelver Islamic scholar states:

If anyone wishes to see the real spirit of Islam, he will find it, not in the deeds of the nouveaux riches of Medina, but in the life, character and deeds of such companions of the Apostle of God as Ali ibn Abi Talib, Salman el-Farsi, Abu Dharr el-Ghiffari, Ammar ibn Yasir, Owais Qarni and Bilal. The orientalists will change their assessment of the spirit of Islam if they contemplate it in the austere, pure and sanctified lives of these latter companions.

— Ali Asgher Razwy, A Restatement of the History of Islam and Muslims[22]

Salman, along with Abu Dharr, Ammar ibn Yasir, and Miqdad ibn Aswad, is considered to be the most loftiest of the Shi'a.

Sufi view

Salman is also well known as a prominent figure in Sufi traditions.[3] Sufi orders such as Qadriyya and Bektashiyya and Naqshbandi have Salman in their Isnad of their brotherhood.[6] In the Oveyssi-Shahmaghsoudi order and Naqshbandi order, Salman is the third person in the chain connecting devotees with Muhammad. The members of futuwwa associations also regarded Salman as one of their founders, along with Ali ibn Abi Talib.[6]

Druze view

Druze tradition honors several “mentors” and “prophets”,[23] and Salman is honored as a prophet, and as an incarnation of the monotheistic idea.[24][25]

Bahá’í view

In the Kitáb-i-Íqán, Bahá'u'lláh honours Salman for having been told about the coming of Muhammad:

As to the signs of the invisible heaven, there appeared four men who successively announced unto the people the joyful tidings of the rise of that divine Luminary. Rúz-bih, later named Salmán, was honoured by being in their service. As the end of one of these approached, he would send Rúz-bih unto the other, until the fourth who, feeling his death to be nigh, addressed Rúz-bih saying: 'O Rúz-bih! when thou hast taken up my body and buried it, go to Hijáz for there the Day-star of Muhammad will arise. Happy art thou, for thou, shalt behold His face!'

Ahmadiyya

In Ahmadiyya, Salman is mentioned in connection with the faith of the Persian people:[26]

Allah's Apostle put his hand on Salman, saying, "If Faith were at (the place of) Ath-Thuraiya (Pleiades, the highest star), even then (some men or man from these people (i.e. Salman's folk) would attain it."

— Sahih Bukhari, Volume 6, Book 60, Hadith 420[27]

See also

- 7th century in Lebanon § Ṣaḥāba who have visited Lebanon

- List of non-Arab Sahabah

- Sulaym ibn Qays

- Salman the Persian (TV series)

References

- ^ Web Admin. "Salman Farsi, the Son of Islam". Sibtayn International Foundation. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- ^ a b An-Nawawi, Al-Majmu', (Cairo, Matbacat at-'Tadamun n.d.), 380.

- ^ a b c d e f Jestice, Phyllis G. (2004). Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 761. ISBN 978-1576073551. Archived from the original on 2018-01-23. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ Adamec, Ludwig W. (2009). Historical Dictionary of Islam. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 276–277.

- ^ a b c d Houtsma & Wensinck (1993). First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. Brill Academic Pub. p. 116. ISBN 978-9004097964.

- ^ a b c d e Zakeri, Mohsen (1993). Sasanid Soldiers in Early Muslim Society: The Origins of 'Ayyārān and Futuwwa. Jremany. p. 306. ISBN 9783447036528. Archived from the original on 2015-11-25. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ^ Milad Milani (2014). Sufism in the Secret History of Persia. Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 9781317544593.

In one particular hadith, Salman mentions he is from Ramhormoz, though this is a reference to his ancestry as his father was transferred from Ramhormoz to Esfahan, residing in Jey (just outside the military camp), which was designed to accommodate the domestic requirements of military personnel.

- ^ Sameh Strauch (Translator) (2006). Mukhtaṣar Sīrat Al-Rasūl. Darussalam. p. 94. ISBN 9789960980324.

{{cite book}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ^ Sahih Bukhari, Book 5, Volume 58, Hadith 283 (Merits of the Helpers in Madinah [Ansaar]). Archived from the original on 2017-04-25. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

Narrated Salman: I am from Ram-Hurmuz (i.e. a Persian town).

- ^ a b "سلمان الفارسي - الصحابة - موسوعة الاسرة المسلمة". Islam.aljayyash.net. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ Hijazi, Abu Tariq (27 Sep 2013). "Salman Al-Farsi — the son of Islam". Arab News. Archived from the original on 7 Dec 2021.

- ^ "Seventh Session, Part 2". Al-islam.org. Archived from the original on 2012-06-09. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ^ Akramulla Syed (2010-03-20). "Salman the Persian details: Early Years in Persia (Iran)". Ezsoftech.com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-16. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ^ Nūrī, Nafas al-raḥmān fī faḍāʾil Salmān, p. 139.

- ^ "Salman al-Farsi", Wikishia, 4/12/2018, http://en.wikishia.net/view/Salman_al-Farsi Archived 2019-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (November 30, 1985). And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 267. ISBN 0807841285.

- ^ "موقع قصة الإسلام - إشراف د/ راغب السرجاني". islamstory.com. Archived from the original on 2012-12-30. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ a b John Walker. "Calendar Converter". fourmilab.ch. Archived from the original on 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- ^ "Rockets hit Shia tomb in Iraq". Al Jazeera. 27 February 2006. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir ibn Rustom al-Tabari. Dalail al-Imamah. p.447.

- ^ A Restatement of the History of Islam and Muslims on Al-Islam.org Umar bin al-Khattab, the Second Khalifa of the Muslims Archived 2006-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ C. Brockman, Norbert (2011). Encyclopedia of Sacred Places, 2nd Edition [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 259. ISBN 9781598846553.

- ^ Dana, Léo-Paul (2010). Entrepreneurship and Religion. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 314. ISBN 9781849806329.

- ^ D Nisan, Mordechai (2015). Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle and Self-Expression, 2d ed. McFarland. p. 94. ISBN 9780786451333.

- ^ ahmadianswers.com

- ^ sunnah.com

External links

- CS1 errors: generic name

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Articles containing Arabic-language text

- Articles with hCards

- Articles containing Persian-language text

- All articles with self-published sources

- Articles with self-published sources from December 2017

- Commons category link is the pagename

- AC with 0 elements

- Translators of the Quran into Persian

- Iranian Muslims

- Iranian former Christians

- People from Kazerun

- 654 deaths

- 568 births

- 6th-century Iranian people

- 7th-century Iranian people

- Converts to Christianity from Zoroastrianism

- Converts to Islam from Christianity

- Muhajirun

- Non-Arab Sahabah

- Governors of the Rashidun Caliphate

- Prophets in the Druze faith