Rider–Waite Tarot

The Rider–Waite Tarot is a widely popular deck for tarot card reading.[1][2] It is also known as the Waite–Smith,[3] Rider–Waite–Smith,[4][5] or Rider Tarot.[4] Based on the instructions of academic and mystic A. E. Waite and illustrated by Pamela Colman Smith, both members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the cards were originally published by the Rider Company in 1909. The deck has been published in numerous editions and inspired a wide array of variants and imitations.[6][7] It is estimated that more than 100 million copies of the deck exist in more than 20 countries.[8]

Overview

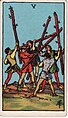

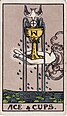

While the images are simple, the details and backgrounds feature abundant symbolism. Some imagery remains similar to that found in earlier decks, but overall the Waite–Smith card designs are substantially different from their predecessors. Christian imagery was removed from some cards, and added to others. For example, the "Papess" became the "High Priestess" and no longer features a Papal tiara, while the "Lovers" card, previously depicting a medieval scene of a clothed man and woman receiving a blessing from a noble or cleric was changed to a depiction of the naked Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and the ace of cups featuring a dove carrying Sacramental bread. The Minor Arcana is illustrated with allegorical scenes by Smith, where earlier decks (with a few rare exceptions) had simple designs for the Minor Arcana.[9]

The symbols and imagery used in the deck were influenced by the 19th-century magician and occultist Eliphas Levi,[10][11] as well as by the teachings of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.[12] In order to accommodate the astrological correspondences taught by the Golden Dawn, Waite introduced several innovations to the deck. He switched the order of the Strength and Justice cards so that Strength corresponded with Leo and Justice corresponded with Libra.[13][14] He also changed the Lovers card to depict two people instead of three in order to reinforce its correspondence with Gemini.[13]

Major Arcana

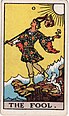

0 – The Fool

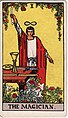

I – The Magician

II – The High Priestess

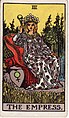

III – The Empress

IV – The Emperor

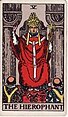

V – The Hierophant

VI – The Lovers

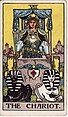

VII – The Chariot

VIII – Strength

IX – The Hermit

X – Wheel of Fortune

XI – Justice

XII – The Hanged Man

XIII – Death

XIV – Temperance

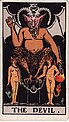

XV – The Devil

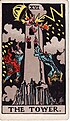

XVI – The Tower

XVII – The Star

XVIII – The Moon

XIX – The Sun

XX – Judgement

XXI – The World

Minor Arcana

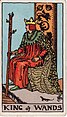

Wands

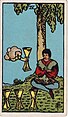

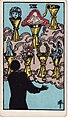

Cups

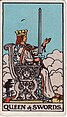

Swords

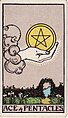

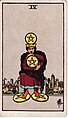

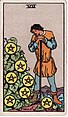

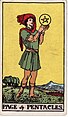

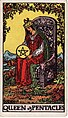

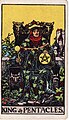

Pentacles

Publication

The cards were first published during December 1909, by the publisher William Rider & Son of London.[9][13] The first printing was extremely limited and featured card backs with a roses and lilies pattern. A much larger printing was done during March of 1910, featuring better quality card stock and a "cracked mud" card back design. This edition, often referred to as the "A" deck, was published from 1910 to 1920. Rider continued publishing the deck in various editions until 1939, then again from 1971 to 1977.

All of the Rider editions up to 1939 were available with a small guide written by A. E. Waite providing an overview of the traditions and history of the cards, texts about interpretations, and extensive descriptions of their symbols. The first version of this guide was published during 1909 and was titled The Key to the Tarot. A year later, a revised version, The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, was issued that featured black-and-white plates of all seventy-eight of Smith's illustrations.

Copyright status

The original version of the Rider–Waite Tarot is in the public domain in all countries that have a copyright term of 70 years or fewer after the death of the last co-author. This includes the United Kingdom, where the deck was originally published.[15]

In the United States, the deck became part of the public domain in 1966 (publication + 28 years + renewed 28 years), and thus has been available for use by American artists for numerous different media projects. U.S. Games Systems has a copyright claim on their updated version of the deck published in 1971, but this only applies to new material added to the pre-existing work (e.g. designs on the card backs and the box).

References

- ^ Giles, Cynthia (1994). The Tarot: History, Mystery, and Lore. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 46. ISBN 0671891014.

- ^ Visions and Prophecies. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books. 1988. p. 142.

- ^ Katz, Marcus; Goodwin, Tali (2015). Secrets of the Waite-Smith Tarot. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 0738741191.

- ^ a b Michelsen, Teresa (2005). The Complete Tarot Reader: Everything You Need to Know from Start to Finish. Llewellyn Publications. p. 105. ISBN 0738704342.

- ^ Graham, Sasha (2018). Llewellyn's Complete Book of the Rider–Waite–Smith Tarot. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 073875319X.

- ^ Kaplan, Stuart R. (2018). Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story. Stamford, Connecticut: U.S. Game Systems. p. 371. ISBN 9781572819122.

- ^ Dean, Liz (2015). The Ultimate Guide to Tarot: A Beginner's Guide to the Cards, Spreads, and Revealing the Mystery of the Tarot. Beverly, Massachusetts: Fair Winds Press. p. 9. ISBN 1592336574.

- ^ Ray, Sharmistha (23 March 2019). "Reviving a Forgotten Artist of the Occult". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ a b Kaplan, Stuart R. (2018). Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story. Stamford, Connecticut: U.S. Game Systems. pp. 74–76. ISBN 9781572819122.

- ^ Place, Robert M. (14 May 2015). "Levi's Chariot and Smith's Chariot Versus Waite's Chariot". Tarot & Divination Decks with Robert M Place. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Place, Robert M. (7 August 2015). "Smith, Waite, Levi, and the Devil". Tarot & Divination Decks with Robert M Place. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Decker, Ronald; Dummett, Michael (2019). A History of the Occult Tarot. London: Duckworth. pp. 139–141. ISBN 9780715645727.

- ^ a b c Jensen, K. Frank (2005). "The Early Waite–Smith Tarot Editions". The Playing-Card. The International Playing Card Society. 34 (1): 26–50.

- ^ Decker, Ronald; Dummett, Michael (2019). A History of the Occult Tarot. London: Duckworth. pp. 82–84. ISBN 9780715645727.

- ^ "Ownership of copyright works - Detailed guidance". GOV.UK. 2014-08-19. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

External links

Learning materials related to A Psychological Interpretation of the Tarot at Wikiversity

Learning materials related to A Psychological Interpretation of the Tarot at Wikiversity