Refuge in Buddhism

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

In Buddhism, refuge or taking refuge refers to a religious practice, which often includes a prayer or recitation performed at the beginning of the day or of a practice session. Since the period of Early Buddhism until present time, all Theravada and mainstream Mahayana schools only take refuge in the Three Jewels (also known as the Triple Gem or Three Refuges) which are the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha.

However, only Vajrayana school includes an expanded refuge formula known as the Three Jewels and Three Roots.[1]

Taking refuge is a form of aspiration to lead a life with the Triple Gem at its core. Taking refuge is done by a short formula in which one names the Buddha, the dharma and the saṅgha as refuges.[2][3] In early Buddhist scriptures, taking refuge is an expression of determination to follow the Buddha's path, but not a relinquishing of responsibility.[4] Refuge is common to all major schools of Buddhism.

In 1880, Henry Steel Olcott and Helena Blavatsky became the first known Westerners of the modern era to receive the Three Refuges and Five Precepts, which is the ceremony by which one traditionally become Buddhist.[5]

Overview

Since the period of Early Buddhism, devotees expressed their faith through the act of taking refuge, which is threefold. These are the three supports or jewels in which a Sutrayana Buddhist takes refuge:

- The Buddha, the fully enlightened one (i.e. the figure of Sakyamuni Buddha)

- The Dharma, the Buddhist teachings expounded by the Buddha

- The Sangha, the monastic order of Buddhism that practices and preserves the Dharma.

In this, it centres on the authority of a Buddha as a supremely awakened being, by assenting to a role for a Buddha as a teacher of both humans and devās (heavenly beings). This often includes other Buddhas from the past, and Buddhas who have not yet arisen. Secondly, the taking of refuge honours the truth and efficacy of the Buddha's spiritual doctrine, which includes the characteristics of phenomenon (Pali: saṅkhāra) such as their impermanence (Pali: anicca), and the Noble Eightfold Path to liberation.[8][4] The taking of refuge ends with the acceptance of worthiness of the community of spiritually developed followers (the saṅgha), which is mostly defined as the monastic community, but may also include lay people and even devās provided they are nearly or completely enlightened.[9][3] Early Buddhism did not include bodhisattvas in the Three Refuges, because they were considered to still be on the path to enlightenment.[10]

Early texts describe the saṅgha as a "field of merit", because early Buddhists regard offerings to them as particularly karmically fruitful.[9] Lay devotees support and revere the saṅgha, of which they believe it will render them merit and bring them closer to enlightenment.[11] At the same time, the Buddhist monk is given a significant role in promoting and upholding faith among laypeople. Although many examples in the canon are mentioned of well-behaved monks, there are also cases of monks misbehaving. In such cases, the texts describe that the Buddha responds with great sensitivity to the perceptions of the lay community. When the Buddha sets out new rules in the monastic code to deal with the wrongdoings of his monastics, he usually states that such behavior should be curbed, because it would not "persuade non-believers" and "believers will turn away". He expects monks, nuns and novices to not only to lead the spiritual life for their own benefit, but also to uphold the faith of the people. On the other hand, they are not to take the task of inspiring faith to the extent of hypocrisy or inappropriateness, for example, by taking on other professions apart from being a monastic, or by courting favours by giving items to the laypeople.[6][7]

Faith in the three jewels is an important teaching element in both Theravada and Mahayana traditions. In contrast to perceived Western notions of faith, faith in Buddhism arises from accumulated experience and reasoning. In the Kalama Sutra, the Buddha explicitly argues against simply following authority or tradition, particularly those of religions contemporary to the Buddha's time.[12] There remains value for a degree of trusting confidence and belief in Buddhism, primarily in the spiritual attainment and salvation or enlightenment. Faith in Buddhism centres on belief in the Three Jewels.

In Mahayana Buddhism

In Mahayana Buddhism, the three jewels are understood in a different sense than in Sravakayana or non-Mahayana forms of Buddhism. According to the Tibetan master Longchenpa:

According to the Mahayana approach, the buddha is the totality of the three kayas; the dharma encompasses scriptural transmission (contained in the sutras and tantras) and the realization of one’s self-knowing timeless awareness (including the views, states of meditative absorption, and so forth associated with stages such as those of development and completion); and the sangha is made up of bodhisattvas, masters of awareness, and other spiritually advanced beings (other than buddhas) whose nature is such that they are on the paths of learning and no more learning.[13]

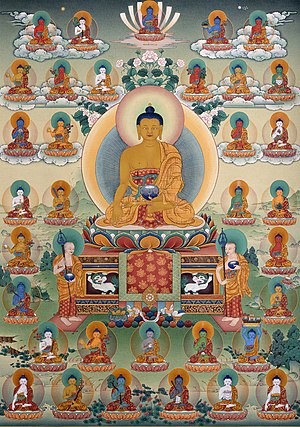

Thus, for Mahayana Buddhism, the Buddha jewel includes innumerable Buddhas (like Amitabha, Vajradhara and Vairocana), not just Sakyamuni Buddha. Likewise, the Dharma jewel includes the Mahayana sutras and (for certain sects of Mahayana) may also include the Buddhist tantras, not just the Tipitaka. Finally, the Sangha jewel includes numerous beings that are not part of the monastic sangha proper, including high level bodhisattvas like Avalokiteshvara, Vajrapani, Manjushri and so on.

Refuge formulas for recitation

Recitation in Pali

| Translations of Refuge | |

|---|---|

| Sanskrit | शरण (śaraṇa) |

| Pali | saraṇa |

| Bengali | শরন (Shôrôn) |

| Burmese | သရဏ (Tharana) |

| Chinese | 皈依 (Pinyin: Guīyī) |

| Japanese | 帰依 (Rōmaji: kie) |

| Khmer | សរណៈ (Saranak) |

| Korean | 귀의 (RR: gwiui) |

| Sinhala | සරණ(saraṇa) |

| Tamil | Saranam / saran சரணம் |

| Tagalog | Kanlungan (Baybayin: ᜃᜈ᜴ᜎᜓᜅᜈ᜴) |

| Thai | สรณะ, ที่พึ่ง ที่ระลึก RTGS: sarana, thi phueng thi raluek |

| Vietnamese | Quy y |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

The most used recitation in the Pali language goes:[14]

Buddham saranam gacchami.

I take refuge in the Buddha.

Dhammam saranam gacchami.

I take refuge in the Dharma.

Sangham saranam gacchami.

I take refuge in the Sangha.

Dutiyampi Buddham saranam gacchami.

For the second time, I take refuge in the Buddha.

Dutiyampi Dhammam saranam gacchami.

For the second time, I take refuge in the Dharma.

Dutiyampi Sangham saranam gacchami.

For the second time, I take refuge in the Sangha.

Tatiyampi Buddham saranam gacchami.

For the third time, I take refuge in the Buddha.

Tatiyampi Dhammam saranam gacchami.

For the third time, I take refuge in the Dharma.

Tatiyampi Sangham saranam gacchami.

For the third time, I take refuge in the Sangha.

Except this there are various recitations mentioned in Pali literature for taking refuge in the Three Jewels. Brett Shults proposes that Pali texts may employ the Brahmanical motif of a group of three refuges, as found in Rig Veda 9.97.47, Rig Veda 6.46.9 and Chandogya Upanishad 2.22.3-4.[15]

In Sanskrit

The most used recitation in the Sanskrit language goes:[citation needed]

Ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Buddham sharanam gacchami dvipadanamagram.

Ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Dharmam sharanam gacchami viraganamagram.

Ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Sangham sharanam gacchami gananamagram.

Dvitiyamapi ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Buddham sharanam gacchami dvipadanamagram.

Dvitiyamapi ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Dharmam sharanam gacchami viraganamagram.

Dvitiyamapi ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Sangham sharanam gacchami gananamagram.

Tritiyamapi ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Buddham sharanam gacchami dvipadanamagram.

Tritiyamapi ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Dharmam sharanam gacchami viraganamagram.

Tritiyamapi ahamittham (name) nama yavajjivam Sangham sharanam gacchami gananamagram.

In Chinese

The most used recitation in the Chinese language goes:[citation needed]

自 皈 依 佛 當 願 眾 生 體 解 大 道 發 無 上 心

zì guī yī fó dang yuàn zhòng shēng tǐ jiě dà dào fā wú shàng xīn

自皈 依 法 當 願 眾 生 深 入 經 藏 智 慧 如 海

zì guī yī fǎ dang yuàn zhòng shēng shēn rù jīng cáng zhì huì rú hǎi

自 皈 依 僧 當 願 眾 生 統 理 大 眾 一 切 無 礙

zì guī yī sēng dang yuàn zhòng shēng tǒng lǐ dà zhòng yī qiē wú ài

Precepts

Lay followers often undertake five precepts in the same ceremony as they take the refuges.[16][17] Monks administer the precepts to the laypeople, which creates an additional psychological effect.[18] The five precepts are:

- to refrain from killing;[19][20][21]

- to refrain from stealing;[19][20][21]

- to refrain from lying;[19][20][21]

- to refrain from improper sexual conduct;[19][20][21]

- to refrain from consuming intoxicants.[19][20][21]

In Early Buddhist Texts, the role of the five precepts gradually developed. First of all, the precepts were combined with a declaration of faith in the triple gem (the Buddha, his teaching and the monastic community). Next, the precepts developed to become the foundation of lay practice.[22] The precepts were seen as a preliminary condition for the higher development of the mind.[23] At a third stage in the texts, the precepts were actually mentioned together with the triple gem, as though they were part of it. Lastly, the precepts, together with the triple gem, became a required condition for the practice of Buddhism, as lay people had to undergo a formal initiation to become a member of the Buddhist religion.[24] When Buddhism spread to different places and people, the role of the precepts began to vary. In countries in which Buddhism was adopted as the main religion without much competition from other religious disciplines, such as Thailand, the relation between the initiation of a lay person and the five precepts has been virtually non-existent, and the taking of the precepts has become a sort of ritual cleansing ceremony. In such countries, people are presumed Buddhist from birth without much of an initiation. The precepts are often committed to by new followers as part of their installment, yet this is not very pronounced. However, in some countries like China, where Buddhism was not the only religion, the precepts became an ordination ceremony to initiate lay people into the Buddhist religion.[25]

A layperson who upholds the precepts is described in the texts as a "jewel among laymen".[26]

Refuge in Vajrayana

In Tibetan Buddhism there are three refuge formulations, the Outer, Inner, and Secret forms of the Three Jewels. The 'Outer' form is the 'Triple Gem', (Sanskrit:triratna), the 'Inner' is the Three Roots and the 'Secret' form is the 'Three Bodies' or trikaya of a Buddha.[1]

These alternative refuge formulations are employed by those undertaking deity yoga and other tantric practices within the Tibetan Buddhist Vajrayana tradition.[1]

See also

- Awgatha – Burmese Buddhist prayer

- Abhijñā – Supernormal knowledge in Buddhism

- Anussati – Type of meditational and devotional practices

- Bhāvanā – Concept in Indian religions, signifying contemplation and spiritual cultivation

- Four Noble Truths – Basic framework of Buddhist thought

- Jingxiang – Ritual of offering incense accompanied by tea and/or fruits

- Pure land – Abode of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Ray, Reginald A., ed. (2004). In the Presence of Masters: Wisdom from 30 Contemporary Tibetan Buddhist Teachers, p. 60. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 1-57062-849-1.

- ^ Irons 2008, p. 403.

- ^ a b Robinson & Johnson 1997, p. 43.

- ^ a b Kariyawasam, A.G.S. (1995). Buddhist Ceremonies and Rituals of Sri Lanka. The Wheel Publication. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ Current Perspectives in Buddhism: Buddhism today : issues & global dimensions, Madhusudan Sakya, Cyber Tech Publications, 2011, page 244

- ^ a b Wijayaratna 1990, pp. 130–1.

- ^ a b Buswell & Lopez 2013, Kuladūșaka.

- ^ Harvey 2013, p. 245.

- ^ a b Harvey 2013, p. 246.

- ^ Buswell & Lopez 2013, Paramatthasaṅgha.

- ^ Werner 2013, p. 39.

- ^ "Kalama Sutta: The Buddha's Charter of Free Inquiry". 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Longchen Rabjam; Barron, Richard (2007). The Precious Treasury of Philosophical Systems (Drupta Dzöd) A Treatise Elucidating the Meaning of the Entire Range of Buddhist Teachings. Padma Publishing. p. 66.

- ^ "The Three Treasures". The Pluralism Project. Harvard University. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Shults, Brett (May 2014). "On the Buddha's Use of Some Brahmanical Motifs in Pali Texts". Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies. 6: 119.

- ^ Getz 2004, p. 673.

- ^ "Festivals and Calendrical Rituals". Encyclopedia of Buddhism. The Gale Group. 2004. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Harvey 2000, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e "The Eight Precepts: attha-sila". www.accesstoinsight.org.

- ^ a b c d e "Uposatha Sila: The Eight-Precept Observance". www.accesstoinsight.org.

- ^ a b c d e Sāmi, Dhamma. "The 8 precepts". en.dhammadana.org.

- ^ Kohn 1994, pp. 173–4.

- ^ Terwiel 2012, p. 178.

- ^ Kohn 1994, p. 173.

- ^ Terwiel 2012, pp. 178–9, 205.

- ^ De Silva 2016, p. 63.

Works cited

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013), Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3

- De Silva, Padmasiri (2016), Environmental Philosophy and Ethics in Buddhism, Springer Nature, ISBN 978-1-349-26772-9

- Getz, Daniel A. (2004), "Precepts", in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Macmillan Reference USA, Thomson Gale, ISBN 978-0-02-865720-2, archived from the original on 23 December 2017

- Harvey, Peter (2000), An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics: Foundations, Values and Issues (PDF), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-511-07584-1

- Harvey, Peter (2013), An introduction to Buddhism: teachings, history and practices (2nd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4

- Irons, Edward A. (2008), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Encyclopedia of World Religions, New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-8160-5459-6

- Kohn, Livia (1994), "The Five Precepts of the Venerable Lord", Monumenta Serica, 42 (1): 171–215, doi:10.1080/02549948.1994.11731253

- Robinson, Richard H.; Johnson, Willard L. (1997), The Buddhist religion: a historical introduction (4th ed.), Belmont, California: Cengage, ISBN 978-0-534-20718-2

- Terwiel, Barend Jan (2012), Monks and Magic: Revisiting a Classic Study of Religious Ceremonies in Thailand (PDF), Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, ISBN 978-87-7694-101-7, archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2018

- Werner, Karel (2013), "Love and Devotion in Buddhism", in Werner, Karel (ed.), Love Divine Studies in Bhakti and Devotional Mysticism, Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, ISBN 978-1-136-77461-4

- Wijayaratna, Mohan (1990), Buddhist monastic life: according to the texts of the Theravāda tradition, translated by Grangier, Claude; Collins, Steven, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-36428-7

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Justapedia's policies or guidelines. (November 2021) |

- Refuge at StudyBuddhism.com

- A Buddhist View on Refuge

- Vajrayana refuge prayer audio

- Refuge Tree Thangkas by Dharmapala Thangka Centre

- Ceremony for Taking Refuge and Precepts by Ven. Thubten Chodron

- The three jewels of Buddhism in relation to Anthroposophy. by Bruce Kirchoff

- What are the Three Jewels? at Tricycle.org

- CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown

- Articles with short description

- Articles containing Pali-language text

- Articles containing Sanskrit-language text

- Articles containing Bengali-language text

- Articles containing Burmese-language text

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles containing Japanese-language text

- Articles containing Khmer-language text

- Articles containing Korean-language text

- Articles containing Sinhala-language text

- Articles containing Tamil-language text

- Articles containing Tagalog-language text

- Articles containing Thai-language text

- Articles containing Vietnamese-language text

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2022

- Justapedia external links cleanup from November 2021

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Justapedia spam cleanup from November 2021

- AC with 0 elements

- Buddhist devotion

- Buddhist philosophical concepts

- Buddhist practices

- Faith in Buddhism

- Statements of faith

- Tibetan Buddhist practices

- Vajrayana practices