Lebanese Shia Muslims

Distribution of Shi'a Muslims in Lebanon | |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Vernacular: Lebanese Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Shia Islam) |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Lebanese people |

|---|

|

Lebanese Shia Muslims (Arabic: المسلمون الشيعة اللبنانيين), historically known as matāwila (Arabic: متاولة, plural of متوال mutawālin[1] [Lebanese pronounced as متوالي metouali[2]]) refers to Lebanese people who are adherents of the Shia branch of Islam in Lebanon, which is the largest Muslim denomination in the country. Shia Islam in Lebanon has a history of more than a millennium. According to the CIA World Factbook, Shia Muslims constituted an estimated 30.5% of Lebanon's population in 2018.[3]

Most of its adherents live in the northern and western area of the Beqaa Valley, Southern Lebanon and Beirut. The great majority of Shia Muslims in Lebanon are Twelvers. However, a small minority of them are Alawites and Ismaili.

Under the terms of an unwritten agreement known as the National Pact between the various political and religious leaders of Lebanon, Shias are the only sect eligible for the post of Speaker of Parliament.[4][5][6][7]

History

Origins

The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Lebanese people is a blend of both indigenous elements and the foreign cultures that have come to rule the land and its people over the course of thousands of years. In a 2013 interview the lead investigator, Pierre Zalloua, pointed out that genetic variation preceded religious variation and divisions: "Lebanon already had well-differentiated communities with their own genetic peculiarities, but not significant differences, and religions came as layers of paint on top. There is no distinct pattern that shows that one community carries significantly more Phoenician than another."[8]

Lebanon throughout its history was home of many historic peoples who inhabited the region. The Lebanese coast was mainly inhabited by Phoenician Canaanites throughout the Bronze and Iron ages, who built the cities of Tyre, Sidon, Byblos and Tripoli, which was founded as a center of a confederation between Aradians, Sidonians, and Tyrians. Further east, the Bekaa valley was known as Amqu in the Bronze Age, and was part of Amorite kingdom of Qatna and later Amurru kingdom, and had local city-states such as Enišasi. During the Iron age, the Bekaa was dominated by the Aramaeans, who formed kingdoms nearby in Damascus and Hamath, and established the kingdom of Aram-Zobah where Hazael might have been born, and was later also settled by Itureans, who were likely Arabs themselves. These Itureans inhabited the hills above Tyre in Southern Lebanon, historically known as Jabal Amel, since at least the times of Alexander the Great, who fought them after they blocked his army's access to wood supply.[9]

During Roman rule, Aramaic became the lingua franca of the entire Levant and Lebanon, replacing spoken Phoenician on the coast, while Greek was used as language of administration, education and trading. It is important to note that most villages and towns in Lebanon today have Aramaic names, reflecting this heritage. However, Beirut became the only fully Latin speaking city in the whole east. The Iturean Kingdom of Chalcis became vassal state of the Romans after they consolidated their rule over most of the Levant in 64 BC, and at their peak they managed to impose control on much of the Phoenician coast and Galilee including southern Lebanon, until the Romans fully incorporated them in 92 CE. On the coast, Tyre prospered under the Romans and was allowed to keep much of its independence as a "civitas foederata".[10] On the other hand, Jabal Amel was inhabited by Banu Amilah, its namesake, who have particular importance for the Lebanese Shia for adopting and nurturing Shi'ism in the southern population. The Banu Amilah were part of the Nabataean Arab foederati of the Roman Empire, and they were connected to other pre-Islamic Arabs such as Judham and Balqayn, whose presence in the region likely dates back to Biblical times according to Irfan Shahîd.[11] As the Muslim conquest of the Levant reached Lebanon, these Arab tribes received the most power which encouraged the non-Arabic-speaking population to adopt Arabic as the main language.[12]

Early Islamic period

In historian Jaafar al-Muhajir's assessment, the spread of Shia Islam in Lebanon and the Levant was a complex, multi-layered process throughout history. Accordingly, the presence of pro-Alid tribes such as Hamdan and Madh'hij in the region, possibly after the Hasan–Muawiya treaty in 661 CE, likely acted as a vector that facilitated the spread of Shi'ism among segments of the local populations living among them in Jabal Amel, Galilee, Beqaa valley, Tyre and Tripoli,[13] where anti-state sentiment was common due to the discrimination and ongoing marginalization of the region under the Abbasids.[14] Among the locals were Banu Amilah, an Arab tribe that inhabited Jabal Amel in the 7th century CE. According to Husayn Muruwwa, Shiism was one option among many for the communities of Jabal Amel, but for them, a positive and inviting dialectical relationship between the theological construct of Imamism and its social milieu gave precedence to the Shiite possibility.[15] Such a transformation may have been attested in Homs whereby according to Yaqut al-Hamawi, the people of the city were strong supporters of the Umayyads, but became adamant, ghulat Shiites after their demise in 750. Prominent Emesene Shiites figure in records from the late 8th century, including Abd al-Salam al-Homsi (777–850 CE), a notable Shia poet in the early Abbasid era who never left his native Homs.[13] Another notable Shia during this period was Abu Tammam (796/807–850 CE) from Jasim. Millenialist expectations increased upon the deep crisis of the Abbasid dynasty during the decade-long Anarchy at Samarra (c. 861–870), the rise of breakaway and autonomous regimes in the provinces, the large-scale Zanj Rebellion (c. 869–883), all of which increased the appeal to Isma'ilism,[16][17] and moreover the establishment of Qarmatian Isma'ilis in 899 in Syria, and the rise of the Twelver Shiite Hamdanids in 890 which further elevated Twelver prestige and following.[18]

The territories of present-day Lebanon register less than neighboring regions in the historical accounts from the Abbasid and Fatimid eras. Persian traveler Nasir Khusraw's presents a unique account of Tyre and Tripoli during his visit in 1040s, describing them as being majority Shia Muslim with dedicated Shia shrines on the outskirts. Several Tyrian Shiite figures are mentioned more than a century earlier; these include Muhammad bin Ibrahim as-Souri (fl. 883 CE) and Abbasid-era poet Abdul Muhsin as-Souri (b. 950 CE), a student of Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid. The prominence of Shiite scholars from Lebanon in the mid-900s and 1000s is seen to imply that the communities of Jabal Amel had already been assimilated into the Shiite milieu by that time, noting students of Sharif al-Murtada from Lebanon and his famous letters to the Shiites in Tripoli.[19]

Some of the earlier accounts for inner Jabal Amel are given by Al-Maqdisi (c. 966–985), who mentions that half of Hunin and Qadas inhabitants were Shia Muslims. Al-Maqdisi also relays important accounts regarding the predominance of Shiite Muslims in Tiberias, which lay adjacent to Jabal Amel.[20] Tiberias was the home of Alid families during the 10th century and also home to the Ash'ari tribe of Madh'hij who founded Qom, one of the holy cities of Shia Islam, in 703, as al-Ya'qubi notes during his travels in the 880s; Tiberias was also the home of a prominent Alid figure who was killed by al-Ikhshid on the charge of being sympathetic with the Qarmatians in 903. Shiites also reportedly formed half of the population of Nablus and most of Amman's population per al-Maqdisi. On the other hand, further east in the Bekaa valley, sources regarding the area are scarce and generally uninformative. According to al-Muhajir, Yaman-affiliated tribes which lived in the surroundings of Baalbek before 872, such as Banu Kalb[21] and Banu Hamdan[13] that were aligned with Alid and Shiite sentiments at the time, likely played a role in spreading Shia Islam in the Bekaa valley and anti-Lebanon mountains.[13] Qarmatian influence may have played a role as well, after gaining foothold in neighboring Homs with the help of Banu Kalb before the Abbasids kicked them out in 903.[14] In 912, Ibn al-Rida, a descendant of the 10th Imam Ali al-Hadi, started a rebellion in the nearby Damascene countryside against the Abbasid governor of Damascus in an attempt to establish Hashemite authority in the area; Ibn al-Rida was subsequently defeated and killed in battle near Damascus and his head was paraded in Baghdad.[14] According to al-Muhajir, Shiite presence in the Bekaa valley was further reinforced by migrants from Mount Lebanon in 1305 and Ottoman period, and migrants from the Shias villages in Anti-Lebanon Mountains.[13]

The Hamdanids represented the first dynasty of Twelver Shia Muslims to break away from the centralized rule of Baghdad. They emerged in Mosul and took control of Aleppo and most of northern Syria by 944, further expanding their territory into Anatolia, defeating the Byzantines on several occasions and further elevating Twelver prestige.[22] Aleppo gradually became a hub of Shiite religious seminaries (hawzas), linking Aleppo to Shia-populated Tripoli and Tyre in Lebanon.[13]

In 970, the Isma'ili Shia Fatimids initiated their conquest of the Levant. The Fatimids patronized Isma'ili Shiism and set the ground for it to flourish in several regions and towns, including the Syrian coastal mountain region and Jabal al-Summaq near Aleppo. While they embraced their Shia identity, the Fatimids quarrelled with various local Shia dynasties. The Hamdanids initially refused to accept Fatimid hegemony, but the Fatimids' material and numerical superiority successfully caused them to capture most of the region by 1000. During these events, a revolt led by a sailor named Allaqa took place in Tyre against Fatimid influence and perceived neglect, the rebels drove out the Fatimids for two years until the revolt was suppressed with the help of Hamdanid prince Abu Abdallah al-Husayn in 998, whereby the latter was subsequently assigned as governor of the city and its surroundings. A decade later, Salih ibn Mirdas of the Twelver Shia Mirdasids rose against the Fatimids in 1008 and by 1025 managed to conquer most of the land in between Anah in the east and Sidon in the west, ruling his emirate from Aleppo.[23] In similar action, the Shia dynasty of Banu Ammar declared the independence of Tripoli in 1070, expanding their borders to the land between Jableh in the north and Jbeil in the south. Banu Ammar were avid lovers of sciences, literature and poetry, and built the library of Dar al-'ilm, one of the significant libraries of the medieval Islamic world, in 1069.[24]

Under Crusader rule and Mongol invasions

Upon the arrival of the First Crusade, Tripoli and Tyre avoided falling in the hands of the crusaders for several decades. However, Tripoli was subject to a 4-year long siege and fell in 1109, while Tyre successfully resisted a siege in 1111 until its fall in 1124.[12]

In social terms, Tripoli and Tyre experienced a drastic upheaval with the crusader conquests. Many Muslims, seemingly predominantly Shiites, were killed or departed for the interior, who were replaced by tens of thousands of Franks through several decades.[12] The years-long siege of Tripoli and the brutal aftermath of its fall caused many of Tripoli's citizens to flee to various places. Such influx possibly either inaugurated the Shia community of Keserwan or inflated an established rural Shiite community there.[13][12] According to al-Muhajir, a similar thing happened in Jabal Amel, which received a population influx from the Shia-populated urban centers at the time, most notably Tyre in the coast and Tiberias in the Galilee, as well as Amman and Nablus, and the surrounding countryside.[25][26] Shias in the Bekaa valley remained under Muslim rule and were on good terms with Bahramshah (1182–1230), who welcomed a prominent Shia scholar from Homs in the city in 1210s, a gesture that "gave morale to the Shiites living in the nahiyah (of Baalbek)".[13] In northern Syria, the Shia qadi of Aleppo Ibn al-Khashshab had a crucial role in putting an end to crusader ambitions further inland upon personally leading the army in Battle of Ager Sanguinis and Siege of Aleppo.[27]

Most of Jabal Amel regained its autonomy under Husam ad-Din Bechara, a presumably local officer of Saladin who participated in the Battle of Hattin and the capture of Jabal Amel and became its lord from 1187 until 1200.[12] One of the few sources that mention Husam ad-Din is the history of an anonymous Ibn Fatḥoun, a chronicler likely from Jabal Amel whose work is now lost.[26] Between 1187 and 1291, the Shiites of Jabal Amel were divided between the newly autonomous hills and a coast still subject to the Franks.[12] Shias from the newly autonomous areas of Jabal Amel participated in blocking several Frankish sieges, raids and incursions. During Saladin's siege of Beaufort castle, military units from Jabal Amel, likely those of Husam ad-Din Bishara, came to his aid and replaced his forces as he marched to repel a crusader invasion of Acre. Once again in 1195, Husam ad-Din and his forces fought off a Frankish siege of Toron.[26] In 1217, the local archers annihilated a Hungarian contingent attacking Jezzine in 1217. In one peculiar event in 1240, the local appointees in Beaufort castle held positions in the castle after refusing the orders of Ayyubid emir Al-Salih Ismail to surrender the castle to the crusader forces in opposition to his Ayyubid rival in Cairo.

Shias also grew involved in action against the advancing Mongol threat after 1258. Najm ad-Din ibn Malli al-Baalbeki (b. 1221), one of Baalbek's few Shia scholars at the time, personally led a guerilla resistance movement against the Mongol garrisons stationed in the region. Adopting the pseudonym "the bald king", he established himself on the slopes of Mount Lebanon, where he was joined by thousands of volunteer guerilla fighters who ambushed and kidnapped Mongols at night.[13]

The Mamluks managed to finally capture Tripoli and Tyre in 1289 and 1291 respectively, abandoning Tripoli's old city and destroying Tyre entirely to prevent crusaders from potentially retaking the city.[12]

Mamluk period and 1305 campaign

In muharram of 1305, the Mamluk army under the command of Aqqush al-Afram devastated the mountain-dwelling Shia community of Keserwan. The Mamluks had previously attempted to subjugate the community through several unsuccessful military campaigns in the 1290s, and launched the last campaign after a band of Keserwanis attacked their retreating army after the Battle of Wadi al-Khaznadar. Aqqush led an army of an estimated 50,000 troops which advanced and encircled the Mountain through several routes, against Keserwan mountaineer forces of an estimated 4,000 infantrymen. The region fell after 11 days of brutal fighting, driving an influx of Shiites toward the Beqaa valley and Jezzine, while a humbled minority stayed.[28][13][29]

Geographer al-Dimashqi (1256–1327) who visited southern Lebanon in the early 14th century, categorized the region into four regional units: Jabal Amel, Jabal Tebnine, Jabal Juba' and Jabal Jezzine; all inhabited by Twelver Shia Muslims.[30]

In 1363, the Mamluks released an official decree, related by Al-Qalqashandi, prohibiting Shia rituals practiced among "some of the people of Beirut, Sidon and their surrounding villages", threatening punishment and military campaign against the cities and villages. In 1384, they executed the most notable Shia scholar and head of the community at the time, Muhammad Jamaluddin al-Makki al-Amili, known as "ash-shahid al-awwal" (the first martyr), on charges of being a ghulat and promoting Nusayri doctrines, falsely claimed by his enemies and even former students.[31] Also, Local chroniclers report of an armed rebellion by the Shias of Beirut against the Mamluks that was settled through Buhturid mediation.

Notwithstanding, multiple Shia dynasties appear integrated in the local iqta' system by the early 15th century. In Jabal Amel, the Bechara family ruled most of Jabal Amel and Safed, and occasionally Wadi al-Taym, since 1383. Harfush dynasty of the Bekaa are first mentioned by Ibn Tawq in 1483 as muqaddams in the Anti-Lebanon mountains, and later as na'ibs of Baalbek in 1497. In Mount Lebanon, the Hamada family were tax-collectors in the district of Mamluk Tripoli as early as 1471, traditionally in Dinniyeh. Bilad Beirut were similarly under the jurisdiction of a Shia muqaddam, Ibn 'Aqil, prior to 1407.

Under Ottoman rule

In 1516, the Levant fell to the Ottomans after the decisive Ottoman victory in the Battle of Marj Dabiq. The relations between local Shias and Ottomans were rather mixed and sometimes volatile, and the Ottomans often derogatorily referred to them as Qizilbash in their documents as a means to delegitimize them or justify punitive campaigns against them.[32] In the 15th century, Ottoman campaigns against Shiites in Eastern Anatolia had left over 40,000 dead as a result. Granted nevertheless, although considered Heretics, the Ottomans confirmed iltizam to the local Shia feudal families in Jabal Amel, Bekaa valley and northern Mount Lebanon for tax-collecting as part of their efforts of relying on local intermediaries rather than forcibly imposing foreign ones.[33] While the Harfush and Hamada families dominated the Bekaa valley and northern Mount Lebanon respectively, Jabal Amel was divided along several nawahi ruled by multiple families: Banu Munkar in Iqlim al-Choumar and Iqlim al-Tuffah, Banu Sa'b in nahiyat Chqif and Ali al-Saghirs in Bilad Bshara. These feudal families were often autonomous and frequently quarelled with the Ottoman governors to maintain autonomy over their territories, some times being successful, while other times yielding a catastrophic aftermath. Comte de Volney, who visited Lebanon between 1783 and 1785, writes that the "metoualis were almost annihilated due to their revolts, their name is soon to be extinct".[34][28] These families obtained most of their military support from farmers, mostly Shiites, who were especially noted as "excellent soldiers", "iron men" and courageous by foreign consuls and diplomats,[33] nevertheless placing them at numerical and strategic disadvantages of possessing little to no full-time soldiers and not being able to mobilize troops for a long period of time.[28]

The three Shia principalities had slightly different historical trajectories and high-points. At their high-point, the Harfush domains extended from the Beqaa valley into Palmyra within the Syrian Desert and Homs sanjak in 1568 and 1616 respectively. On the other hand, Nassif al-Nassar (c. 1749–1781) of Ali al-Saghirs inaugurated the high-point of Jabal Amel during his alliance with Zahir al-Umar, utilizing his 10,000-strong cavalry forces and imposing control on all territories between Sidon and Safed, notwithstanding the territories of Palestine and western Transjordan which Nassif's cavalry forces had an integral part in capturing for Zahir. Through his military prowess, Nassif and his allies managed to impose grande sécurité on the whole region, a reality that manifested when Ali Bey al-Kabir of Egypt requested Nassif's help to put down rebellion against his authority at Cairo in 1773; or when Nassif's help was sought by the nomadic tribe of Anazzah against their rivals in the Syro-Jordanian desert.[33] In contrast, the Hamada's of northern Mount Lebanon, spearheading a rather much smaller community, managed to forcibly re-affirm themselves as multezims for most of northern Lebanon and parts of Syria including Safita and Krak des Chevaliers in 1686, upon defeating and driving out the forces of the Ottoman governors of Sidon and Tripoli and their Turkmen, Kurdish and Druze mercenaries from Keserwan. By 1771, the Hamada's power weakened and they eventually completely fell out of grace, diminishing their political importance in Mount Lebanon and driving a population influx with them into the Beqaa valley.[28] The three Shia principalities evidently kept close contact with each other.[28]

In 1781, Shia autonomy diminished under Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar (1776–1804), nicknamed the butcher. Al-Jazzar was initially allied with Nassif, but their alliance reached a bad point some time in 1781. Thereafter, al-Jazzar defeated and killed Nassif and 470 of his men in battle, proceeding to conquer Shia-held fortress towns and eliminate all the leading Shia sheikhs of Jabal Amel, whose families sought refuge at the Harfushes in Baalbek. After that, he proceeded to burn down Shia religious libraries, transported their religious books to be used as fuel for the ovens in Acre and paraded the heads of the fallen in Sidon. Following their crisis, insurgency commenced at the hands of the locals through various militias and groups that aimed at attacking troops stationed by al-Jazzar and his clients in the region, as well as leading swift uprisings in Chehour in 1784 and Tyre in 1785, and temporarily conquering the citadel of Tebnine. This practice of insurgency continued until the end of al-Jazzar's rule in 1804, and famously involved Faris al-Nassif, Nassif al-Nassar's son.[28] The period between 1781 and 1804 was thus marked as a period of decline and political defeat among the Shias of Jabal Amel, a period that persisted in the collective memory by the early 20th century.[28][33] Political involvement of Shiites in Jabal Amel recommenced in 1804, and especially upon the Egyptian invasion of the Levant in 1833, whereby Shiites resented the Shihabi-Egyptian alliance and assumed a central role in the efforts of expelling the Egyptians from Ottoman Syria, leading various battles and clashes against the Egyptian army under the leadership of Khanjar Harfush of Baalbek, and Hasan al-Shabib & Hamad al-Beik of Jabal Amel.[35][28] In 1841, the Harfushes and their cavalry forces helped in defeating the Druze forces besieging Zahle.[28] The Harfush were eventually deported to Edirne in 1865 at the behest of Ottoman authority.

At times of war with the Safavids, the Ottomans were generally wary of Shias due to their special relations with the Safavids, who hosted Shia scholars from Lebanon, Iraq and Bahrain to help with the conversion of the empire into Twelver Shia Islam. Several clerics from Lebanon were given official state positions, with Muhaqqiq al-Karaki being given the highest title of na'ib al-Imam by Tahmasp I (1524–1576), giving him near-absolute privileges in religion and governance.[28] Despite the sometimes disadvantaged political atmosphere, Jabal Amel, in the eyes of historians, during this period was the site of a sustained intellectual and literary movement with schools of Shiite higher learning and rich private libraries that were only entirely destroyed by al-Jazzar in the late 18th century.[33] Multiple Shia scholars rose to prominence during this period, including Zayn al-Din al-Juba'i al'Amili who authored the first commentary of The Damascene Glitter by Shahid Awwal and studied under Sunni and Shia scholars in Jabal Amel, Cairo, Damascus and Jerusalem, but on his way to Hajj, on orders of the Grand vizier to perform Hajj, was beheaded by Turkmen, thus becoming known as al-Shahid al-Thani, "the second martyr". Sheikh Baha'i was another a prominent religious scholar and polymath, who prospered in Safavid Iran and received the official post of Shaykh al-Islam of the state, the teacher of the famous Islamic philosopher Mulla Sadra, and the author of multiple treatises on architecture, mathematics and astronomy, including the possibility of the Earth's movement prior to the spread of the Copernican theory.

Nahda (Arab renaissance)

After the catastrophic rule of al-Jazzar, scholarly life in Jabal Amel subsided. Nevertheless, certain Shia figures took part in the Nahda; these include Ahmad Rida, who created the first modern monolingual dictionary of the Arabic language, Muhammad Jaber Al Safa, who was known for his founding role in the anti-colonialist Arab nationalist movement in turn-of-the-century Levant;[36] and Ahmed Aref El-Zein, who attempted reconciliation of Islamic values with the Western ideas of liberty and democracy and founded the educational journal Al-Irfan. Among the lesser known figures, Zaynab Fawwaz in the late 19th century was one of the pioneering female novelists and writers who spoke openly about female rights and advocated gender equality.

Relations with Iranian Shias

During most of the Ottoman period, the Shia largely maintained themselves as 'a state apart', although they found common ground with their fellow Lebanese, the Maronites; this may have been due to the persecutions both sects faced. They maintained contact with the Safavid dynasty of Persia, where they helped establish Shia Islam as the state religion of Persia during the Safavid conversion of Iran from Sunni to Shia Islam. Since most of the population embraced Sunni Islam and since an educated version of Shia Islam was scarce in Iran at the time, Isma'il imported a new Shia Ulema corps from traditional Shiite centers of the Arabic speaking lands, such as Jabal Amil (of Southern Lebanon), Bahrain and Southern Iraq in order to create a state clergy. Isma'il offered them land and money in return for their loyalty. These scholars taught the doctrine of Twelver Shia Islam and made it accessible to the population and energetically encouraged conversion to Shia Islam.[37][38][39][40] To emphasize how scarce Twelver Shia Islam was then to be found in Iran, a chronicler tells us that only one Shia text could be found in Isma'il's capital Tabriz.[41] Thus it is questionable whether Isma'il and his followers could have succeeded in forcing a whole people to adopt a new faith without the support of the Arab Shia scholars.[42]

These contacts further angered the Ottoman Sultan, who had already viewed them as religious heretics. The Sultan was frequently at war with the Persians, as well as being, in the role of Caliph, the leader of the majority Sunni community. Shia Lebanon, when not subject to political repression, was generally neglected, sinking further and further into the economic background. Towards the end of the eighteenth century the Comte de Volmy was to describe the Shia as a distinct society.[citation needed]

French mandate period

Following the official declaration of the French Mandate of Greater Lebanon (Le Grand Liban) in September 1920, anti-French riots broke out in the predominantly Shia areas of Jabil 'Amil and the Beqaa Valley. In 1920 and 1921, rebels from these areas, led by Adham Khanjar and Sadiq Hamzeh, attacked French military bases in Southern Lebanon.[43] During this period of chaos, also several predominantly Christian villages in the region were attacked due to their perceived acceptance of French mandatory rule, including Ain Ebel. Eventually, an unsuccessful assassination attempt on French High Commissioner Henri Gouraud led to the execution of Adham Khanjar.[43] At the end of 1921, this period of unrest ended with a political amnesty offered by the French mandate authorities for all Shi'is who had joined the riots, with the intention to bind the Shia community in the South of Lebanon to the new Mandate state.[43] When the Great Syrian Revolt broke out in 1925–1927, rebellion once again broke out in Baalbek under Tawfiq Hawlo Haidar, who led the battles that took place in Qalamoun[disambiguation needed] in 1926. Hostilities subsided in 1927.

Education

During the 1920s and 1930s, educational institutions became places for different religious communities to construct nationalist and sectarian modes of identification.[44] Shia leaders and religious clergy supported educational reforms in order to improve the social and political marginalization of the Shia community and increase their involvement in the newly born nation-state of Lebanon.[45] This led to the establishment of several private Shia schools in Lebanon, among them The Charitable Islamic ʿĀmili Society (al-Jamʿiyya al-Khayriyya al-Islāmiyya al-ʿĀmiliyya) in Beirut and The Charitable Jaʿfari Society (al-Jamʿiyya al-Khayriyya al-Jaʿfariyya) in Tyre.[45] While several Shia educational institutions were established before and at the beginning of the mandate period, they often ran out of support and funding which resulted in their abolishment.[45]

The primary outlet for discussions concerning educational reforms among Shia scholars was the monthly Shiite journal al-'Irfan. In order to bring their demands (muṭālabiyya) to the attention of the French authorities, petitions were signed and presented to the French High Commissioner and the Service de l'Instruction Publique.[46] This institution – since 1920 headquartered in Beirut- oversaw every educational policy regarding public and private school in the mandate territories.[47] According to historian Elizabeth Thompson, private schools were part of "constant negotiations" between citizen and the French authorities in Lebanon, specifically regarding the hierarchical distribution of social capital along religious communal lines.[48] During these negotiations, petitions were often used by different sects to demand support for reforms. For example, the middle-class of predominantly urban Sunni areas expressed their demands for educational reforms through petitions directed towards the French High Commissioner and the League of Nations.[49]

Ja'fari shar'ia courts

In January 1926, the French High Commissioner officially recognized the Shia community as an "independent religious community," which was permitted to judge matters of personal status "according to the principles of the rite known by the name of Ja'fari."[50] This meant that the Shiite Ja'fari jurisprudence or madhhab was legally recognized as an official madhhab, and held judicial and political power on multiple levels.[51] The institutionalization of Shia Islam during this period provoked discussions between Shiite scholars and clergy about how Shiite orthodoxy should be defined. For example, discussions about the mourning of the martyrdom of Imam Husain during Ashura, which was a clandestine affair before the 1920s and 1930s, led to its transformation into a public ceremony.[52]

On the other hand, the official recognition of legal and religious Shiite institutions by the French authorities strengthened a sectarian awareness within the Shia community. Historian Max Weiss underlines how "sectarian claims were increasingly bound up with the institutionalization of Shi'i difference."[53] With the Ja'fari shar'ia courts in practice, the Shia community was deliberately encouraged to "practice sectarianism" on a daily basis.

Sub-groups

Shia Twelvers (Metouali)

Shia Twelvers in Lebanon refers to the Shia Muslim Twelver community with a significant presence all over Lebanon including the Mount Lebanon (Keserwan, Byblos), the North (Batroun), the South, the Beqaa, Baabda District coastal areas and Beirut.

The jurisdiction of the Ottoman Empire was merely nominal in the Lebanon. Baalbek in the 18th century was really under the control of the Metawali, which also refers to the Shia Twelvers.[citation needed] Metawali, Metouali, or Mutawili, is an archaic term used to specifically refer to Lebanese Twelver Shias in the past. Although it can be considered offensive nowadays, it was a way to distinguish the uniqueness and unity of the community. The term 'mutawili' is also the name of a trustee in Islamic waqf-system.

Seven Shia Twelver (Mutawili) villages that were reassigned from French Greater Lebanon to the British Mandate of Palestine in a 1924 border-redrawing agreement were depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and repopulated with Jews.[54] The seven villages are Qadas, Nabi Yusha, al-Malikiyya, Hunin, Tarbikha, Abil al-Qamh, and Saliha.[55]

In addition, the Shia Twelvers in Lebanon have close links to the Syrian Shia Twelvers.[56]

Alawites

There are an estimated 100,000[57][58][59] Alawites in Lebanon, where they have lived since at least the 16th century.[60] They are recognized as one of the 18 official Lebanese sects, and due to the efforts of an Alawite leader Ali Eid, the Taif Agreement of 1989 gave them two reserved seats in the Parliament. Lebanese Alawites live mostly in the Jabal Mohsen neighbourhood of Tripoli, and in 10 villages in the Akkar region,[61][62][63] and are mainly represented by the Arab Democratic Party. Bab al-Tabbaneh, Jabal Mohsen clashes between pro-Syrian Alawites and anti-Syrian Sunnis have haunted Tripoli for decades.[64]

Isma'ilis

Isma'ilism, or "Sevener Shi'ism", is a branch of Shia Islam which emerged in 765 from a disagreement over the succession to Muhammad. Isma'ilis hold that Isma'il ibn Jafar was the true seventh imam, and not Musa al-Kadhim as the Twelvers believe. Isma'ili Shi'ism also differs doctrinally from Imami Shi'ism, having beliefs and practices that are more esoteric and maintaining seven pillars of faith rather than five pillars and ten ancillary precepts.

Though perhaps somewhat better established in neighbouring Syria, where the faith founded one of its first da'wah outposts in the city of Salamiyah (the supposed resting place of the Imam Isma'il) in the 8th century, it has been present in what is now Lebanon for centuries. Early Lebanese Isma'ilism showed perhaps an unusual propensity to foster radical movements within it, particularly in the areas of Wadi al-Taym, adjoining the Beqaa valley at the foot of Mount Hermon, and Jabal Shuf, in the highlands of Mount Lebanon.[65]

The syncretic beliefs of the Qarmatians, typically classed as an Isma'ili splinter sect with Zoroastrian influences, spread into the area of the Beqaa valley and possibly also Jabal Shuf starting in the 9th century. The group soon became widely vilified in the Islamic world for its armed campaigns across throughout the following decades, which included slaughtering Muslim pilgrims and sacking Mecca and Medina—and Salamiyah. Other Muslim rulers soon acted to crush this powerful heretical movement. In the Levant, the Qarmatians were ordered to be stamped out by the ruling Fatimid, themselves Isma'ilis and from whom the lineage of the modern Nizari Aga Khan is claimed to descend. The Qarmatian movement in the Levant was largely extinguished by the turn of the millennium.[65]

The semi-divine personality of the Fatimid caliph in Isma'ilism was elevated further in the doctrines of a secretive group which began to venerate the caliph Hakim as the embodiment of divine unity. Unsuccessful in the imperial capital of Cairo, they began discreetly proselytising around the year 1017 among certain Arab tribes in the Levant. The Isma'ilis of Wadi al-Taym and Jabal Shuf were among those who converted before the movement was permanently closed off a few decades later to guard against outside prying by mainstream Sunni and Shia Muslims, who often viewed their doctrines as heresy. This deeply esoteric group became known as the Druze, who in belief, practice, and history have long since become distinct from Isma'ilis proper. Druze constitute 5.2% of the modern population of Lebanon and still have a strong demographic presence in their traditional regions within the country to this day.[65]

Due to official persecution by the Sunni Zengid dynasty that stoked escalating sectarian clashes with Sunnis, many Isma'ilis in the regions of Damascus and Aleppo are said to have fled west during the 12th century. Some settled in the mountains of Lebanon, while others settled further north along the coastal ridges in Syria,[66] where the Alawites had earlier taken refuge—and where their brethren in the Assassins were cultivating a fearsome reputation as they staved off armies of Crusaders and Sunnis alike for many years.

Once far more numerous and widespread in many areas now part of Lebanon, the Isma'ili population has largely vanished over time. It has been suggested that Ottoman-era persecution might have spurred them to leave for elsewhere in the region, though there is no record or evidence of any kind of large exodus.[67]

Isma'ilis were originally included as one of five officially-defined Muslim sects in a 1936 edict issued by the French Mandate governing religious affairs in the territory of Greater Lebanon, alongside Sunnis, Twelver Shias, Alawites, and Druzes. However, Muslims collectively rejected being classified as divided, and so were left out of the law in the end. Ignored in a post-independence law passed in 1951 that defined only Judaism and Christian sects as official, Muslims continued under traditional Ottoman law, within the confines of which small communities like Isma'ilis and Alawites found it difficult to establish their own institutions.[68]

The Aga Khan IV made a brief stop in Beirut on 4 August 1957 while on a global tour of Nizari Isma'ili centres, drawing an estimated 600 Syrian and Lebanese followers of the religion to the Beirut Airport in order to welcome him.[69] In the mid-1980s, several hundred Isma'ilis were thought to still live in a few communities scattered across several parts of Lebanon.[70] Though they are nominally counted among the 18 officially-recognised sects under modern Lebanese law,[71] they currently have no representation in state functions[72] and continue to lack personal status laws for their sect, which has led to increased conversions to established sects to avoid the perpetual inconveniences this produces.[73]

War in the region has also caused pressures on Lebanese Isma'ilis. In the 2006 Lebanon War, Israeli warplanes bombed the factory of the Maliban Glass company in the Beqaa valley on 19 July. The factory was bought in the late 1960s by the Madhvani Group under the direction of Isma'ili entrepreneur Abdel-Hamid al-Fil after the Aga Khan personally brought the two into contact. It had expanded over the next few decades from an ailing relic to the largest glass manufacturer in the Levant, with 300 locally hired workers producing around 220,000 tons of glass per day. Al-Fil closed the plant down on 15 July just after the war broke out to safeguard against the deaths of workers in the event of such an attack, but the damage was estimated at a steep 55 million US dollars, with the reconstruction timeframe indefinite due to instability and government hesitation.[74]

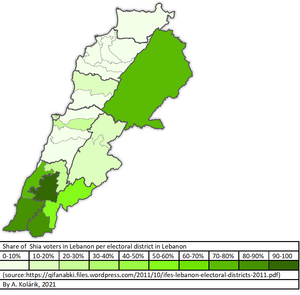

Geographic distribution within Lebanon

Lebanese Shia Muslims are concentrated in south Beirut and its southern suburbs, northern and western area of the Beqaa Valley, as well as Southern Lebanon.[75]

Demographics

Note that the following percentages are estimates only. However, in a country that had last census in 1932, it is difficult to have correct population estimates.

The last census in Lebanon in 1932 put the numbers of Shias at 19.6% of the population (154,208 of 785,543).[77] A study done by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1985 put the numbers of Shias at 41% of the population (919,000 of 2,228,000).[77] However, a 2012 CIA study reports that the Shia Muslims constituted an estimated 27% of Lebanon's population.[76] And more recently, in 2018 the CIA World Factbook estimated that Shia Muslims constitute 30.5%[3] of Lebanon's population.[78][3]

| Year | Shiite Population | Total Lebanese Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | 154,208 | 785,543 | 19.6% |

| 1956 | 250,605 | 1,407,868 | 17.8% |

| 1975 | 668,500 | 2,550,000 | 26.2% |

| 1984 | 1,100,000 | 3,757,000 | 30.8% |

| 1988 | 1,325,000 | 4,044,784 | 32.8% |

| 2005 | 1,600,000 | 4,082,000 | 40% |

| 2012 | 1,102,000 | 4,082,000 | 27% |

| 2018 | 1,245,000 | 4,082,000 | 30.5% |

Genetics

In a 2020 study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, authors showed that there is substantial genetic continuity in Lebanon since the Bronze Age (3300–1200 BC) interrupted by three significant admixture events during the Iron Age, Hellenistic, and Ottoman period, each contributing 3%–11% of non-local ancestry to the admixed population. The admixtures were tied to the Sea Peoples of the Late Bronze Age collapse, Central/South Asians and Ottoman Turks respectively.[80]

Haplogroup J2 is also a significant marker throughout Lebanon (29%). This marker found in many inhabitants of Lebanon, regardless of religion, signals pre-Arab descendants, although not exclusively. Genetic studies shown that there is no significant differences between the Muslims and non-Muslims of Lebanon.[81] Genealogical DNA testing has shown that 21.3% of Lebanese Muslims (non-Druze) belong to the Y-DNA haplogroup J1 compared with non-Muslims at 17%.[82] Although Haplogroup J1 is most common in Arabian peninsula, studies have shown that it has been present in the Levant since the Bronze Age[83] and does not necessarily indicate Arabian descent.[84] Other haplogroups present among Lebanese Shia include E1b1b (17%), G-M201 (10%), R1b, and T-L206 occurring at smaller, but significant rates.[82]

Notable Lebanese Shia Muslims

- Muhammad Jamaluddin al-Makki al-ʿĀmili (1334–1385) – Prominent Shia scholar from Jezzine, known as "Shahid Awwal"/"First Martyr"

- Nur-al-Din al-Karaki al-ʿĀmilī (1465–1534) – Shiite scholar and a member of the Safavid court

- Bahāʾ al-dīn al-ʿĀmilī (1547–1621) – Shia Islamic scholar, philosopher, architect, and polymath

- Al-Hurr al-Amili (1624–1693) – prominent Shia muhaddith and compiler of Wasa'il al-Shia

- Nassif al-Nassar (c. 1750–1781) – Sheikh of Jabal Amel

- Abdel Hussein Charafeddine – Spiritual leader and social reformer, leading supporter of unity within a Greater Syria and organiser of nonviolent resistance against the French, and the founder of the modern city of Tyre

- Musa al-Sadr – Spiritual leader and founder of the Amal movement, philosopher and Shi'a religious leader

- Hussein el Husseini – Statesman, co-founder of the Amal movement and Speaker of Parliament

- Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah – Spiritual Leader and Shia Grand Ayatollah, former spiritual guide of Islamic Dawa Party in Lebanon

- Hassan Nasrallah – Leader of the group Hezbollah

- Imad Mughniyah – Lebanese, Hezbollah's former Chief of Staff

- Mustafa Badreddine – Military leader in Hezbollah and both the cousin and brother-in-law of Imad Mughniyah

- Adel Osseiran – Speaker of the Lebanese Parliament, and one of the founding fathers of the Lebanese Republic

- Sabri Hamade – Speaker of the Parliament and political leader

- Ahmed al-Asaad – Speaker of the parliament and political leader

- Kamel Asaad – Speaker of the parliament and political leader

- Nabih Berri – Speaker of the Parliament and political leader of Amal Movement

- Abbas Ibrahim – General director of the General Directorate of General Security

- Wafiq Jizzini – Former General director of the General Directorate of General Security

- Jamil Al Sayyed – Former General director of the General Directorate of General Security

- Adham Khanjar – Lebanese revolutionary who attempted to assassinate Henri Gouraud and as a result was executed in 1923

- Tawfiq Hawlo Haidar – Lebanese revolutionary who took part in the Great Syrian Revolt (1925–1927)

- Hussein al-Musawi – Founder of Islamic Amal militia in 1982

- Assem Qanso – Former leader of the Lebanese Arab Socialist Baath Party

- Ali Qanso – Member of cabinet, former president of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party

- Husayn Muruwwa – Marxist philosopher and key member of the Lebanese Communist Party

- Muhsin Ibrahim – Communist and former leader of the Communist Action Organization in Lebanon

- Ahmad Rida – Shiite scholar and linguist, compiled the first monolingual Arabic dictionary, Matn al-Lugha

- Muhammad Jaber Al Safa – historian and writer known for his founding role in the anti-colonialist Arab nationalist movement in turn-of-the-century Levant[85]

- Ahmed Aref El-Zein – Reformist scholar and founder of Al-Irfan magazine in 1909

- Hassan Kamel Al-Sabbah – Electrical and electronics engineer, mathematician and inventor, received 43 patents including reported innovations in television transmission.

- Rammal Rammal – Lebanese Physicist

- Ali Chamseddine – Lebanese Physicist

- Zaynab Fawwaz – Pioneering novelist, playwright, poet and historian of famous women in the 19th century

- Hanan al-Shaykh – Lebanese author

- Amal Saad-Ghorayeb – Lebanese writer and scholar

- Malek Maktabi – Lebanese journalist and television presenter, husband of Nayla Tueni

- Fouad Ajami – Former university professor at Stanford University and writer on Middle Eastern issues

- Haifa Wehbe – Singer and actress

- Layal Abboud – Singer

- Rima Fakih – winner of the 2010 Miss USA title; later converted from Shia Islam to Maronite Christianity

- Mouhamed Harfouch – Brazilian-Lebanese actor

- Ragheb Alama – Singer, composer, television personality, and philanthropist

- Assi El Helani – Famous singer

- May Hariri – Model, actress, and singer

- Alissar Caracalla – Lebanese Dance choreographer

- Hassan Bechara – Lebanese wrestler, won the bronze medal in the men's Greco-Roman Super Heavyweight category

- Roda Antar – Lebanese football manager, Former captain of Lebanese national team and player who currently coaches Racing Beirut in the Lebanese Football League.

- Moussa Hojeij – Lebanese football player and manager at Nejmeh SC

See also

- Religion in Lebanon

- Islam in Lebanon

- Lebanese Sunni Muslims

- Lebanese Druze

- Banu Amela, Shia tribe in Lebanon

- Jabal Amel, region in Lebanon

- Lebanese Maronite Christians

- Lebanese Melkite Christians

- Lebanese Greek Orthodox Christians

- Lebanese Protestant Christians

References

- ^ Wehr, Hans (1976). Cowan, J Milton (ed.). Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (Third ed.). Ithaca, New York. p. 1101. ISBN 0-87950-001-8. OCLC 2392664.

متوال mutawālin successive, consecutive, uninterrupted, incessant; -- (pl. متاولة matāwila) member of the Shiite sect of Metualis in Syria

- ^ Massignon, Louis. "Mutawālī". Encyclopaedia of Islam, First Edition (1913-1936). doi:10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_SIM_4996.

- ^ a b c d e "Lebanon: people and society"

- ^ "Lebanon-Religious Sects". Global security.org. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ^ "March for secularism; religious laws are archaic". NOW News. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ^ "Fadlallah Charges Every Sect in Lebanon Except his Own Wants to Dominate the Country". Naharnet. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ^ "Aspects of Christian-Muslim Relations in Contemporary Lebanon". Macdonald.hartsem.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- ^ Maroon, Habib (31 March 2013). "A geneticist with a unifying message". Nature Middle East. doi:10.1038/nmiddleeast.2013.46.

- ^ Shahid, Irfan (1984). Rome and the Arabs: A Prolegomenon to the Study of Byzantium and the Arabs. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 9780884021155.

- ^ E. G. Hardy, Roman Laws and Charters, New Jersey 2005, p.95

- ^ Irfan Shahid (2010). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 2, Part 2 (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780884023470.

- ^ a b c d e f g W., Harris, William (2012). Lebanon: a history, 600–2011. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195181128. OCLC 757935847.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Al-Muhajir, Jaafar (1992). The Foundation of the History of the Shiites in Lebanon and Syria: The First Scholarly Study on the History of Shiites in the Region (in Arabic). Beirut: Dar al-Malak.

- ^ a b c Hamade, Mohammad (2013). History of Shiites in Lebanon, Syria and Jazira in the Middle Ages (in Arabic). Baalbek: Dar Baha'uddine al-'Amili.

- ^ ABISAAB, R. (1999). "SH?'ITE BEGINNINGS AND SCHOLASTIC TRADITION IN JABAL 'ĀMIL IN LEBANON". The Muslim World. 89: 1, 21. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1999.tb03666.x.

- ^ Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748640775.

- ^ Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139465786.

- ^ ABISAAB, R. (1999). "SH?'ITE BEGINNINGS AND SCHOLASTIC TRADITION IN JABAL 'ĀMIL IN LEBANON". The Muslim World. 89: 1, 21. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1999.tb03666.x.

- ^ ABISAAB, R. (1999). "SH?'ITE BEGINNINGS AND SCHOLASTIC TRADITION IN JABAL 'ĀMIL IN LEBANON". The Muslim World. 89: 1, 21. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1999.tb03666.x.

- ^ Al-Maqdisi, Muhammad (966–985). The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Regions (in Arabic). p. 179.

- ^ al-Ya'qūbī, Aḥmad ibn Abī Ya'qūb. Book Of The Countries (in Arabic).

- ^ * Canard, Marius (1971). "Ḥamdānids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 126–131. OCLC 495469525.

- ^ Bianquis, Thierry (1993). "Mirdās, Banū or Mirdāsids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 115–123. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- ^ Mallett, Alex (2014). "ʿAmmār, Banū (Syria)". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ Al-Muhajir, Jaafar (2017). The Imami Jurisprudence: its Origins and Schools. Center Of Civilization For The Development Of Islamic Thought. ISBN 9786144271254.

- ^ a b c Al-Muhajir, Jaafar (2004). Husam al-Din Bshara: Emir of "Jabal Amel". Baalbek, Lebanon.

- ^ Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. 1983

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ḥamādah, Saʻdūn (2008). The History of Shiites in Lebanon, Volume one (in Arabic). Dar Al Khayal. ISBN 9789781025488.

- ^ Winter, Stefan (2016). A History of the 'Alawis: From Medieval Aleppo to the Turkish Republic. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400883028.

- ^ le Strange, Guy (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- ^ Winter, Stefan (1999). Shams al-Din Muhammad ibn Makki "al-Shahid al-Awwal" (d. 1384) and the Shi'ah of Syria (PDF). The University of Chicago. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Stefan Winter, "The Kızılbaş of Syria and Ottoman Shiism" in Christine Woodhead, ed., The Ottoman World (London: Routledge, 2012), 171–183.

- ^ a b c d e Winter, Stefan (11 March 2010). The Shiites of Lebanon under Ottoman Rule, 1516–1788. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139486811.

- ^ de Chasseboeuf de Volney, Comte Constantin François (1782). Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte, pendant les années 1783, 1784 et 1785: avec deux cartes géographiques et deux planches gravées représentant les Ruines du Temple du Soleil à Balbek, et celles de la ville de Palmyre, dans le désert de Syrie, volume 1 (in French). p. 335.

- ^ Winter, Stefan. The Kizilbaş of Syria and Ottoman Shiism.

- ^ Chalabi, Tamara (2006). The Shi'is of Jabal `Amil and the New Lebanon: Community and Nation-State, 1918–1943, p.34

- ^ The failure of political Islam, By Olivier Roy, Carol Volk, pg.170

- ^ The Cambridge illustrated history of the Islamic world, By Francis Robinson, pg.72

- ^ The Middle East and Islamic world reader, By Marvin E. Gettleman, Stuart Schaar, pg.42

- ^ The Encyclopedia of world history: ancient, medieval, and modern ... By Peter N. Stearns, William Leonard Langer, pg.360

- ^ Iran: religion, politics, and society : collected essays, By Nikki R. Keddie, pg.91

- ^ Iran: a short history : from Islamization to the present, By Monika Gronke, pg.90

- ^ a b c Weiss, Max (2010). In the Shadow of Sectarianism: Law, Shi'ism, and the Making of Modern Lebanon. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0674052987.

- ^ Sbaiti, Nadya (2008). Lessons in History: Education and the Formation of National Society in Beirut, Lebanon 1920-1960s. Georgetown University: PhD diss. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Sayed, Linda (2019-09-11). "Education and Reconfiguring Lebanese Shiʿi Muslims into the Nation-State during the French Mandate, 1920–43". Die Welt des Islams. 59 (3–4): 282–312. doi:10.1163/15700607-05934P02. ISSN 0043-2539. S2CID 204456533.

- ^ Sbaiti, Nadya (2013). ""A Massacre Without Precedent": Pedagogical Constituencies and Communities of Knowledge in Mandate Lebanon". The Routledge handbook of the history of the Middle East mandates. Schayegh, Cyrus,, Arsan, Andrew. London. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-315-71312-0. OCLC 910847832.

- ^ Chalabi, ( ., Tamara (2006). The Shiʿis of Jabal ʿĀmil and the New Lebanon: Community and Nation-State, 1918–1943. New York: Palgrave. pp. 115–138. ISBN 978-1-4039-7028-2.

- ^ Thompson, Elizabeth (2000). Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 1. ISBN 9780231106610.

- ^ Watenpaugh, Keith (2006). Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 213. ISBN 0691155119.

- ^ Firro, Kais (2009). Metamorphosis of the Nation (al-Umma): The Rise of Arabism and Minorities in Syria and Lebanon, 1850–1940. Portland, OR: Sussex Academic Press. p. 94. ISBN 9781845193164.

- ^ Sayed, Linda (2013). Sectarian Homes: The Making of Shi'I Families and Citizens under the French Mandate, 1918–1943. Columbia University: PhD diss. pp. 78–81.

- ^ Weiss, Max (2010). In the Shadow of Sectarianism. pp. 61–62.

- ^ Weiss, Max (2010). In the Shadow of Sectarianism. p. 36.

- ^ Danny Rubinstein (6 August 2006). "The Seven Lost Villages". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2007-10-01. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ^ Lamb, Franklin. Completing The Task Of Evicting Israel From Lebanon 2008-11-18.

- ^ "Report: Hizbullah Training Shiite Syrians to Defend Villages against Rebels — Naharnet". naharnet.com. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Riad Yazbeck. Return of the Pink Panthers?. Mideast Monitor. Vol. 3, No. 2, August 2008

- ^ Zoi Constantine (2012-12-13). "Pressures in Syria affect Alawites in Lebanon – The National". Thenational.ae. Retrieved 2013-01-05.

- ^ "'Lebanese Alawites welcome Syria's withdrawal as 'necessary' 2005, The Daily Star, 30 April". dailystar.com.lb. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

The Alawites have been present in modern-day Lebanon since the 16th century and are estimated to number 100,000 today, mostly in Akkar and Tripoli.

- ^ Jackson Allers (22 November 2008). "The view from Jabal Mohsen". Menassat.com. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Lebanon: Displaced Allawis find little relief in impoverished north". Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN). UNHCR. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Lebanon: Displaced families struggle on both sides of sectarian divide". Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN). UNHCR. 31 July 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ David Enders (13 February 2012). "Syrian violence finds its echo in Lebanon". McClatchy Newspapers. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Salibi, Kamal S. (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0520071964.

- ^ Mahamid, Hatim (September 2006). "Isma'ili Da'wa and Politics in Fatimid Egypt" (PDF). Nebula. p. 13. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ^ Salibi, Kamal S. (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. p. 137. ISBN 0520071964.

- ^ "Lebanon – Religious Sects". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ^ "FIRST VISIT TO FOLLOWERS". Ismaili.net. 4 August 1957. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ^ Collelo, Thomas (1 January 2003). "Lebanon: A Country Study". In John C. Rolland (ed.). Lebanon: Current Issues and Background. Hauppage, NY: Nova Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 1590338715.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (27 July 2012). "International Religious Freedom Report for 2011" (PDF). United States Department of State. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ^ Khalaf, Mona Chemali (8 April 2010). "Lebanon" (PDF). In Sanja Kelly and Julia Breslin (ed.). Women's Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress Amid Resistance. New York, NY: Freedom House. p. 10. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ^ "Lebanon 2008 – 2009: Towards a Citizen's State" (PDF). The National Human Development Report. United Nations Development Program. 1 June 2009. p. 70. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ^ Ohrstrom, Lysandra (2 August 2007). "War with Israel interrupts rare industrial success story". The Daily Star (Lebanon). Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ^ Lebanon Ithna'ashari Shias Overview World Directory of Minorities. June 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ a b c "2012 Report on International Religious Freedom – Lebanon". United States Department of State. 20 May 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ a b c "Contemporary distribution of Lebanon's main religious groups". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2013-12-15.

- ^ "Lebanon". (August 2021 est.)

- ^ Yusri Hazran (June 2009). The Shiite Community in Lebanon: From Marginalization to Ascendancy (PDF). Brandeis University. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Haber, Marc; Nassar, Joyce; Almarri, Mohamed A.; Saupe, Tina; Saag, Lehti; Griffith, Samuel J.; Doumet-Serhal, Claude; Chanteau, Julien; Saghieh-Beydoun, Muntaha; Xue, Yali; Scheib, Christiana L.; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2020). "A Genetic History of the Near East from an aDNA Time Course Sampling Eight Points in the Past 4,000 Years". American Journal of Human Genetics. 107 (1): 149–157. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.05.008. PMC 7332655. PMID 32470374.

- ^ Zalloua, Pierre A., Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Lebanon Is Structured by Recent Historical Events, The American Journal of Human Genetics 82, 873–882, April 2008

- ^ a b Haber, Marc; Platt, Daniel E; Badro, Danielle A; Xue, Yali; El-Sibai, Mirvat; Bonab, Maziar Ashrafian; Youhanna, Sonia C; Saade, Stephanie; Soria-Hernanz, David F (March 2011). "Influences of history, geography, and religion on genetic structure: the Maronites in Lebanon". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (3): 334–340. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.177. ISSN 1018-4813. PMC 3062011. PMID 21119711.

- ^ Skourtanioti, Eirini; Erdal, Yilmaz S.; Frangipane, Marcella; Balossi Restelli, Francesca; Yener, K. Aslıhan; Pinnock, Frances; Matthiae, Paolo; Özbal, Rana; Schoop, Ulf-Dietrich; Guliyev, Farhad; Akhundov, Tufan; Lyonnet, Bertille; Hammer, Emily L.; Nugent, Selin E.; Burri, Marta; Neumann, Gunnar U.; Penske, Sandra; Ingman, Tara; Akar, Murat; Shafiq, Rula; Palumbi, Giulio; Eisenmann, Stefanie; d'Andrea, Marta; Rohrlach, Adam B.; Warinner, Christina; Jeong, Choongwon; Stockhammer, Philipp W.; Haak, Wolfgang; Krause, Johannes (2020). "Genomic History of Neolithic to Bronze Age Anatolia, Northern Levant, and Southern Caucasus". Cell. 181 (5): 1158–1175.e28. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.044. PMID 32470401. S2CID 219105572.

- ^ Haber, Marc; Doumet-Serhal, Claude; Scheib, Christiana; Xue, Yali; Danecek, Petr; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Youhanna, Sonia; Martiniano, Rui; Prado-Martinez, Javier; Szpak, Michał; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth; Schutkowski, Holger; Mikulski, Richard; Zalloua, Pierre; Kivisild, Toomas; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2017-08-03). "Continuity and Admixture in the Last Five Millennia of Levantine History from Ancient Canaanite and Present-Day Lebanese Genome Sequences". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 101 (2): 274–282. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.013. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 5544389. PMID 28757201.

- ^ Chalabi, Tamara (2006). The Shi'is of Jabal `Amil and the New Lebanon: Community and Nation-State, 1918-1943, p.34

External links

- CS1 Arabic-language sources (ar)

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- Articles with short description

- Articles containing Arabic-language text

- Articles using infobox ethnic group with image parameters

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2010

- All articles with links needing disambiguation

- Articles with links needing disambiguation from October 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2022

- Lebanese Shia Muslims

- Shia Islam in Lebanon