Jean VI d'Aumont

Jean VI d'Aumont | |

|---|---|

| Seigneur de Aumont | |

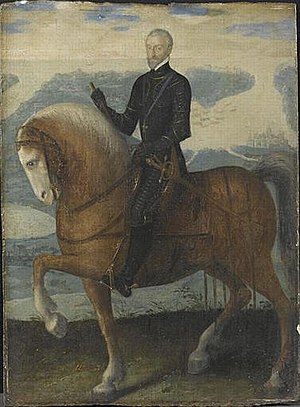

Equestrian portrait of Jean VI, from the Musée Condé | |

| Other titles | Marshal of France |

| Born | January 1522 Châteauroux, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 19 August 1595 (aged 73) Château de Comper, Kingdom of France |

| Family | Maison d'Aumont |

| Spouse(s) | Antoinette Chabot |

| Father | Pierre III d'Aumont |

| Mother | Françoise de Sully |

Jean VI d'Aumont (1522-1595) was a soldier and Marshal of France. He served as Marshal under Henri III, playing a key role in the Day of the Barricades and Assassination of the Duke of Guise (1588). Upon the assassination of Henri III in 1589, he would transfer his loyalties to the Protestant Navarre and would campaign for him in Burgundy, Maine and Brittany against the Duke of Mercœur. He was also granted the office of governor of Dauphiné, upon it being vacated in 1592. It would be whilst fighting in Brittany in 1595, that he would be killed.

Early life and family

Aumont was from an old noble family, which is recorded as far back as the thirteenth century.[1]

Reign of Henri III

Day of the Barricades

Aumont was among those nobles who in 1588, was less concerned with matters of the Ligue than the duels of Les Mignons and affairs of the court.[2] During the Day of the Barricades the angry population demanded the removal of the French and Swiss troops in the capital. The king relented, and instructed O, Alphonse, Biron and Aumont to remove the soldiers from the city. Unable to tolerate the domination of the Guise over him that the day of the Barricades had brought about, the king decided to have them assassinated.[3]

Assassination of the duke of Guise

While staying at Blois in December the king informed Guise of his intention to retreat to his château at La Noue for Christmas and his desire that the whole council meet prior to departing. Guise duly attended, but was puzzled by the presence of many nobles who did not usually attend council, among them Aumont.[4] He sought an explanation but none was provided for the Marshals presence. After the meeting was concluded Guise was invited into a side chamber with the king, where many nobles stabbed him to death. The Cardinal of Guise, and the Archbishop of Lyons who had remained in the chamber heard the commotion, and attempted to rush in to support their kinsmen and ally. Aumont put his hand on his sword, and as an officer of the crown forbade them , and any others in the room from moving on pain of death.[5]

With the kings death a short while later, Aumont was among the nobility that recognised Navarre as king, even prior to his conversion to Catholicism.[6]

Reign of Henri IV

Aumont campaigned in Burgundy for Navarre in 1591, sweeping all before him in the countryside. He was however unable to make inroads into the ligue bastions of Auxerre and Mâcon.[7] In 1592 Navarre appointed him as governor of Dauphiné, replacing Montpensier, he would hold this office until his death.[8] The same year he campaigned in Maine seeking to reverse the royal loss at the Battle of Craon, he captured Mayenne and would take Laval in 1594.[9] In 1593 his campaigning moved to Brittany, where, with the support of Conti he advanced on the Duke of Mercœur.[10] To this end he was in command of 7000 soldiers, which were entirely mercenary in composition.[11] It was during fighting in Brittany that he died in 1595.[12]

Sources

- Harding, Robert (1978). Anatomy of a Power Elite: the Provincial Governors in Early Modern France. Yale University Press.

- Knecht, Robert (2010). The French Wars of Religion, 1559-1598. Routledge.

- Morenas, Henri (1934). Grand Armorial de France. Ėditions Heraldique.

- Salmon, J.H.M (1975). Society in Crisis: France during the Sixteenth Century. Metheun & Co.

References

- ^ Morenas 1934, p. 284.

- ^ Salmon 1975, p. 245.

- ^ Knecht 2010, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Knecht 2010, p. 121.

- ^ Knecht 2010, p. 122.

- ^ Salmon 1975, p. 258.

- ^ Salmon 1975, p. 265.

- ^ Harding 1978, p. 223.

- ^ http://angot.lamayenne.fr/notice/T1C01_BIO0105

- ^ Salmon 1975, p. 267.

- ^ Harding 1978, p. 77.

- ^ Salmon 1975, p. 294.