Avatamsaka Sutra

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Chinese Buddhist Canon |

|---|

|

| Sections |

| Tibetan Buddhist canon |

|---|

|

| 1. Kangyur |

| 2. Tengyur |

The Avataṃsaka Sūtra (IAST, Sanskrit: 𑀅𑀯𑀢𑀁𑀲𑀓 𑀲𑀽𑀢𑁆𑀭) or Buddhāvataṃsaka-nāma-mahāvaipulya-sūtra (The Mahāvaipulya Sūtra named “Buddhāvataṃsaka”) is one of the most influential Mahāyāna sutras of East Asian Buddhism. In Classical Sanskrit, avataṃsaka means garland, wreath, or any circular ornament, such as an earring.[1] Thus, the title may be rendered in English as A Garland of Buddhas, Buddha Ornaments, or Buddha’s Garland.[1] In Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, the term avataṃsaka means “a great number,” “a multitude,” or “a collection.” This is matched by the Tibetan title of the sutra, which is A Multitude of Buddhas ("sangs rgyas phal po che").[1]

The Buddhāvataṃsaka has been described by the translator Thomas Cleary "the most grandiose, the most comprehensive, and the most beautifully arrayed of the Buddhist scriptures."[2]

The Avataṃsaka Sūtra describes a cosmos of infinite realms upon realms, mutually containing one another. This sutra was especially influential in East Asian Buddhism.[3] The vision expressed in this work was the foundation for the creation of the Huayan school of Chinese Buddhism, which was characterized by a philosophy of interpenetration. The Huayan school is known as Hwaeom in Korea and Kegon in Japan. The sutra is also influential in Chan Buddhism.[3]

Title

This work has been used in a variety of countries. Some major traditional titles include the following:

- Sanskrit: Buddhāvataṃsaka-nāma-mahāvaipulya-sūtra, The Mahāvaipulya Sūtra named “Buddhāvataṃsaka”. Vaipulya ("extensive") refers to key Mahayana sutras.[4] "Garland/wreath/adornment" refers to a manifestation of the beauty of Buddha's virtues[5] or his inspiring glory.[N.B. 1] The term avataṃsaka also means “a great number,” “a multitude,” or “a collection.” This matches the content of the sutra, in which numerous Buddhas are depicted as manifestations of the cosmic Buddha Vairocana.[1]

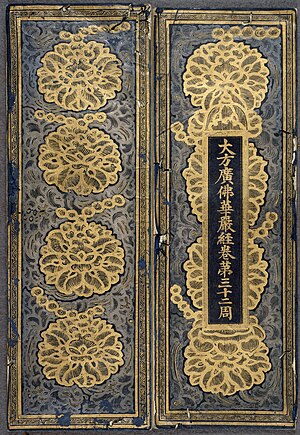

- Chinese: Dàfāngguǎng Fóhuāyán Jīng 大方廣佛華嚴經, commonly known as the Huāyán Jīng (華嚴經), meaning "Flower-adorned (Splendid & Solemn) Sūtra." Vaipulya here is translated as "corrective and expansive", fāngguǎng (方廣).[8] Huā (華) means at once "flower" (archaic; namely 花) and "magnificence." Yán (嚴), short for zhuàngyán (莊嚴), means "to decorate (so that it is solemn, dignified)."

- Japanese: Daihōkō Butsu-kegon Kyō (大方広仏華厳経), usually known as the Kegon Kyō (華厳経). This title is identical to Chinese above, just in Shinjitai characters.

- Korean: 대방광불화엄경 Daebanggwang Bulhwaeom Gyeong or Hwaeom Gyeong (화엄경), the Sino-Korean pronunciation of the Chinese name.

- Vietnamese: Đại phương quảng Phật hoa nghiêm kinh, shortened to the Hoa nghiêm kinh, the Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation of the Chinese name.

- Tibetan: མདོ་ཕལ་པོ་ཆེ།, Wylie: mdo phal po che, Standard Tibetan Do phalpoché

- Tangut (romanized): Tha cha wa tha fa sho ldwi rye

According to a Dunhuang manuscript, this text was also known as the Bodhisattvapiṭaka Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra.[7]

History

The Avataṃsaka Sūtra was written in stages, beginning from at least 500 years after the death of the Buddha. One source claims that it is "a very long text composed of a number of originally independent scriptures of diverse provenance, all of which were combined, probably in Central Asia, in the late third or the fourth century CE."[9] Japanese scholars such as Akira Hirakawa and Otake Susumu meanwhile argue that the Sanskrit original was compiled in India from sutras already in circulation which also bore the name "Buddhavatamsaka".[10]

Two full Chinese translations of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra were made. Fragmentary translation probably began in the 2nd century CE, and the famous Ten Stages Sutra, often treated as an individual scripture, was first translated in the 3rd century. The first complete Chinese version was translated by Buddhabhadra around 420 in 60 scrolls with 34 chapters,[11] and the second by Śikṣānanda around 699 in 80 scrolls with 40 chapters.[12][13] There is also a translation of the Gaṇḍavyūha section by Prajñā around 798. The second translation includes more sutras than the first, and the Tibetan translation, which is still later, includes many differences with the 80 scrolls version. Scholars conclude that sutras were being added to the collection.

The single extant Tibetan version was translated from the original Sanskrit by Jinamitra et al. at the end of ninth century.[14]

According to Paramārtha, a 6th-century monk from Ujjain in central India, the Avataṃsaka Sūtra is also called the "Bodhisattva Piṭaka."[7] In his translation of the Mahāyānasaṃgrahabhāṣya, there is a reference to the Bodhisattva Piṭaka, which Paramārtha notes is the same as the Avataṃsaka Sūtra in 100,000 lines.[7]Identification of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra as a "Bodhisattva Piṭaka" was also recorded in the colophon of a Chinese manuscript at the Mogao Caves: "Explication of the Ten Stages, entitled Creator of the Wisdom of an Omniscient Being by Degrees, a chapter of the Mahāyāna sūtra Bodhisattvapiṭaka Buddhāvataṃsaka, has ended."[7]

Overview

The sutra, among the longest Buddhist sutras, is a compilation of disparate texts on various topics such as the Bodhisattva path, the interpenetration of phenomena (dharmas), the omnipresence of Buddhahood, the miraculous powers of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas, the visionary powers of meditation, and the equality of things in emptiness.[15][16]

According to Paul Demiéville, the Avatamsaka collection is "characterized by overflowing visionary images, which multiply everything to infinity, by a type of monadology that teaches the interpenetration of the one whole and the particularized many, of spirit and matter" and by "the notion of a gradual progress towards liberation through successive stages and an obsessive preference for images of light and radiance."[17] Likewise, Alan Fox has described the sutra's worldview as "fractal", "holographic", and "psychedelic".[18]

The East Asian view of the text is that it expresses the universe as seen by a Buddha (the Dharmadhatu), who sees all phenomena as empty and thus infinitely interpenetrating, from the point of view of enlightenment.[17] This interpenetration is described in the Avatamsaka as the perception "that the fields full of assemblies, the beings and aeons which are as many as all the dust particles, are all present in every particle of dust."[19] Thus, a Buddha's view of reality is also said to be "inconceivable; no sentient being can fathom it".[19]

Paul Williams notes that the sutra speaks of both Yogacara and Madhyamaka doctrines, stating that all things are empty of inherent existence and also of a "pure untainted awareness or consciousness (amala-citta) as the ground of all phenomena".[20] The Avatamsaka sutra also highlights the visionary and mystical power of attaining the spiritual wisdom which sees the nature of the world:

Endless action arises from the mind; from action arises the multifarious world. Having understood that the world's true nature is mind, you display bodies of your own in harmony with the world. Having realized that this world is like a dream, and that all Buddhas are like mere reflections, that all principles [dharma] are like an echo, you move unimpeded in the world (Trans in Gomez, 1967: lxxxi)[20]

As a result of their meditative power, Buddhas have the magical ability to create and manifest infinite forms, and they do this in many skillful ways out of great compassion for all beings.[21]

- In all atoms of all lands

- Buddha enters, each and every one,

- Producing miracle displays for sentient beings:

- Such is the way of Vairocana....

- The techniques of the Buddhas are inconceivable,

- All appearing in accord with beings’ minds....

- In each atom the Buddhas of all times

- Appear, according to inclinations;

- While their essential nature neither comes nor goes,

- By their vow power they pervade the worlds.(Cleary 1984–7: I, Bk 4)

The point of these teachings is to lead all beings through the ten bodhisattva levels to the goal of Buddhahood (which is done for sake of all other beings). These stages of spiritual attainment are also widely discussed in various parts of the sutra (book 15, book 26).[17]

The sutra also includes numerous Buddhas and their Buddhalands which are said to be infinite, representing a vast cosmic view of reality, though it centers on a most important figure, the Buddha Mahavairocana ("Great Radiance" or "The Great Illuminator"). Vairocana is a cosmic being who is the source of light and enlightenment of the 'Lotus universe', and who is said to contain all world systems within his cosmic body.[17] According to Paul Williams, the Buddha "is said or implied at various places in this vast and heterogeneous sutra to be the universe itself, to be the same as ‘absence of intrinsic existence’ or emptiness, and to be the Buddha's all-pervading omniscient awareness."[21] The very body of Vairocana is also seen as a reflection of the whole universe:

The body of [Vairocana] Buddha is inconceivable. In his body are all sorts of lands of sentient beings. Even in a single pore are countless vast oceans.[22]

Also, for the Avatamsaka, the historical Buddha Sakyamuni is simply a magical emanation of the cosmic Buddha Vairocana.[21]

Chapter overview

Luis Gomez notes that there is an underlying order to the collection. The discourses in the sutra version with 39 chapters or books are delivered to eight different audiences or "assemblies" in seven locations such as Bodh Gaya and the Tusita Heaven.[23] Each "assembly" includes various locales, doctrinal topics and characters. The main "assemblies" which the collection is traditionally divided into are:[23][24]

At the Bodhimaṇḍa (Books 1–5)

In this assembly at the Bodhimaṇḍa (the seat of awakening under the bodhi tree), the bodhisattva Samantabhadra and the Buddha discuss the nature of reality and how Vairocana Buddha is omnipresent throughout the dharmadhātu.

The Hall of Universal Light (Books 6–12)

The bodhisattva Mañjuśrī asks the Buddha about the various ways that the four noble truths (which are the basis of all bodhisattva practice) are taught. The bodhisattva Bhadramukha also teaches the Bodhisattva Path.

Indra's Palace (Books 13–18)

The Buddha teaches in Trāyastriṃśa Heaven at the Palace of Indra. Dharmamati teaches on how the bodhisattva path progresses in ten abodes or viharas.

Yama's Palace (Books 19–22)

The Buddha teaches on how the world is a mental creation and provides the famous simile of the world being like a painting and the mind being the painter. The bodhisattva Gunavana teaches the ten practices (carya) of bodhisattvas and the ten inexhaustible treasuries.

Tusita Heaven (Books 23–25)

Vajradhvaja teaches the ways that bodhisattvas dedicate and transfer their merit.

Paranirmitavasavartin Heaven (Book 26)

This is the Ten Stages Sutra (Daśabhūmika sutra), which focuses on the ten bhūmis (levels or stages) of the bodhisattva path.

The Hall of Universal Light part 2 (Books 27–38)

The Buddha returns to the hall of universal light and Samantabhadra teaches the ten samadhis, supernormal powers, and ten types of patience (kshanti). Various other teachings on the bodhisattva path are given, which recapitulate the themes covered in the previous books. The immeasurability of Buddhahood is discussed and Samantabhadra is said to embody all the activities of the omnipresent Buddhahood.

Jetavana Pavillion (Book 39)

This is the Gaṇḍavyūha Sūtra, which contains the story of the bodhisattva Sudhana's spiritual career, study under numerous teachers and his inconceivable liberation.

Individual sutras

At least two parts of the Avatamsaka collection also circulated as individual sutras: the Ten Stages Sutra and the Flower Array Sutra. These two sutras have also survived individually in the original Sanskrit (while the rest of the Avatamsaka only survives in translation).[25]

Ten Stages Sutras

The sutra is also well known for its detailed description of the course of the bodhisattva's practice through ten stages where the Ten Stages Sutra, or Daśabhūmika Sūtra (十地經, Wylie: 'phags pa sa bcu pa'i mdo), is the name given to this chapter of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. This sutra gives details on the ten stages (bhūmis) of development a bodhisattva must undergo to attain supreme enlightenment. The ten stages are also depicted in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra and the Śūraṅgama Sūtra. The sutra also touches on the subject of the development of the "aspiration for Enlightenment" (bodhicitta) to attain supreme buddhahood.

The Flower Array Sutra

The last chapter of the Avatamsaka circulates as a separate and important text known as the Gaṇḍavyūha Sutra (" flower-array", or "bouquet";[26] 入法界品 ‘Entering the Dharma Realm’[27]). Considered the "climax" of the larger text,[28] this section details the pilgrimage of the layman Sudhana to various lands (worldly and supra-mundane) at the behest of the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī to find a spiritual friend who will instruct him in the ways of a bodhisattva. According to Luis Gomez, this sutra can also be "regarded as emblematic of the whole collection."[23]

Despite the former being at the end of the Avataṃsaka, the Gaṇḍavyūha and the Ten Stages are generally believed to be the oldest written chapters of the sutra.[29]

English translations

The first relatively complete English translation of the contents of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra was authored by the late Thomas Cleary and published by Shambhala Publications in 1984. Although this fact is for the most part only known by scholars who have studied the sutra closely in its original Asian language editions, Thomas Cleary's translation of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra was actually only partially translated from Śikṣānanda's most complete and now standard Tang Dynasty edition. Cleary chose instead to translate fully a third of this scripture (the very long and detailed Chapter 26 and the immense 53-part Chapter 39) from the much later P.L. Vaidya Sanskrit, this even though he claimed on page two of his introduction to have made his Flower Ornament Scripture translation from the Śikṣānanda edition. This is clearly not true, for Cleary's translations of Chapters 26 and 39 do not follow Śikṣānanda's Chinese at all, whereas they do follow the often very different P.L. Vaidya Sanskrit edition fairly closely from beginning to end. Beginning in 1984, Cleary's translation was divided into three volumes. The latest edition, from 1993, is contained in a large single volume spanning 1656 pages. One wonders if perhaps this amazing condensation from three volumes down to one volume might have been accomplished by eliminating countless paragraph breaks, for in one instance, Cleary's 1993 edition of the translation goes through eleven pages of very intricately detailed scripture without allowing even a single paragraph break.

- The Flower Ornament Scripture : A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sūtra (1993) by Thomas Cleary,[30] ISBN 0-87773-940-4

Bhiksu Dharmamitra has recently produced from Tripitaka Master Śikṣānanda's 699 ce Sanskrit-to-Chinese edition (T0279) the first and so far only complete English translation of any edition of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra. It is published by Kalavinka Press in three volumes (totaling 2,500 pages) as The Flower Adornment Sutra: An Annotated Translation of the Avataṃsaka Sutra with A Commentarial Synopsis of the Flower Adornment Sutra (October 1st, 2022 / ISBNS: Volume One - 9781935413356; Volume Two - 9781935413363; Volume Three - 9781935413370). (His complete translation of Chapter 39 which corresponds precisely to the Gaṇḍavyūha is contained in Volume Three of this work. It includes the traditionally appended conclusion to Chapter 39, "The Conduct and Vows of Samantabhadra" which was originally translated into Chinese in 798 ce by Tripitaka Master Prajñā.)

Kalavinka Press also published the Daśabhūmika Sūtra (corresponding to Chapter 26 of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra) as an independent text as: The Ten Grounds Sutra: The Daśabhūmika Sūtra: the Ten Highest Levels of Practice on the Bodhisattva's Path to Buddhahood (2019). This was translated by Bhikshu Dharmamitra from Tripitaka Master Kumārajīva’s circa 410 ce Sanskrit-to-Chinese translation of the Daśabhūmika Sūtra (T0286).

The publisher Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai (BDK) has finished editing and is currently (as of July, 2022) in the process of preparing for publication an unannotated multi-volume edition of Bhikshu Dharmamitra's Flower Adornment Sutra which also includes Bhikshu Dharmamitra's translation of the traditionally appended conclusion to Chapter 39, "The Conduct and Vows of Samantabhadra" originally translated by Tripitaka Master Prajñā.

Both the Gaṇḍavyūha and the Daśabhūmika (which together constitute approximately one third of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra have been independently translated from the Tibetan version by Peter Alan Roberts along with 84000.co as:

- The Ten Bhūmis Chapter from the Mahāvaipulya Sūtra “A Multitude of Buddhas” [31]

- “The Stem Array” Chapter from the Mahāvaipulya Sūtra “A Multitude of Buddhas” [32]

These translations are freely available on the 84000 website.

The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas is also producing a translation of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra (which they title The Great Means Expansive Buddha Flower Adornment Sutra) along with a lengthy commentary by Venerable Hsuan Hua.[33] Currently over twenty volumes are available, and it is estimated that there may be 75-100 volumes in the complete edition.

See also

- Indra's net

- List of sutras

- Mahayana sutras

- Shin'yaku Kegonkyō Ongi Shiki, an early Japanese annotation

- Huayan school, named after this sutra

- Kegon school, Japanese Huayan

- Multiverse

References

- ^ The Divyavadana also calls a Śrāvastī miracle Buddhāvataṃsaka, namely, he created countless emanations of himself seated on lotus blossoms.[6][7]

- ^ a b c d "The Stem Array | 84000 Reading Room". 84000 Translating The Words of The Budda. Translated by Peter Alan Roberts. Retrieved 2022-06-06.

- ^ Thomas Cleary. Entry into the Inconceivable: An Introduction to Hua-Yen Buddhism. Shambhala.

- ^ a b Thomas Cleary (1993). The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra. p. 2.

- ^ Keown, Damien (2003). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860560-7.

- ^ Akira Hirakawa; Paul Groner (1990). A history of Indian Buddhism: from Śākyamuni to early Mahāyāna. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1203-4. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

The term "avatamsaka" means "a garland of flowers," indicating that all the virtues that the Buddha has accumulated by the time he attains enlightenment are like a beautiful garland of flowers that adorns him.

- ^ Akira Sadakata (15 April 1997). Buddhist Cosmology: Philosophy and Origins. Kōsei Pub. Co. p. 144. ISBN 978-4-333-01682-2. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

...adornment, or glorious manifestation, of the Buddha[...]It means that countless buddhas manifest themselves in this realm, thereby adorning it.

- ^ a b c d e Ōtake Susumu (2007), "On the Origin and Early Development of the Buddhāvataṃsaka-Sūtra", in Hamar, Imre (ed.), Reflecting Mirrors: Perspectives on Huayan Buddhism, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 89–93, ISBN 978-3-447-05509-3, retrieved 12 June 2011

- ^ Soothill, W.E.; Hodous, Lewis (1937). A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms. London: Trübner. Archived from the original on 2009-03-02.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Gimello, Robert M. (2005) [1987]. "Huayan". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 6 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan. pp. 4145–4149. ISBN 978-0-02-865733-2.

- ^ Hamar, Imre (Editor). Reflecting Mirrors: Perspectives on Huayan Buddhism (ASIATISCHE FORSCHUNGEN), 2007, page 92

- ^ "Taisho Tripitaka No. 278". Archived from the original on 2012-06-18. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ "Taisho Tripitaka No. 279". Archived from the original on 2012-05-23. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ Hamar, Imre (2007), The History of the Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra. In: Hamar, Imre (editor), Reflecting Mirrors: Perspectives on Huayan Buddhism (Asiatische Forschungen Vol. 151), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, ISBN 344705509X, pp.159-161

- ^ Imre Hamar, ed. (2007). Reflecting Mirrors: Perspectives on Huayan Buddhism. Asiatische Forschungen. p. 87.

- ^ Takeuchi Yoshinori (editor). Buddhist Spirituality: Indian, Southeast Asian, Tibetan, and Early Chinese, page 160

- ^ Thomas Cleary (1993). The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sūtra. pp. 31–46. ISBN 0877739404.

- ^ a b c d Takeuchi Yoshinori (editor). Buddhist Spirituality: Indian, Southeast Asian, Tibetan, and Early Chinese, page 161

- ^ Fox, Alan. The Practice of Huayan Buddhism, 2015.04, http://www.fgu.edu.tw/~cbs/pdf/2013%E8%AB%96%E6%96%87%E9%9B%86/q16.pdf Archived 2017-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Paul Williams; Anthony Tribe; Alexander Wynne. Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition. p. 168.

- ^ a b Paul Williams; Anthony Tribe; Alexander Wynne. Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition. p. 121.

- ^ a b c Paul Williams. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. p. 122.

- ^ Ryûichi Abé. The Weaving of Mantra: Kûkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. p. 285.

- ^ a b c Takeuchi Yoshinori (editor) (1995). Buddhist Spirituality: Indian, Southeast Asian, Tibetan, and Early Chinese, p. 164. Motilal Banarsidass.

- ^ Cleary, Thomas (1993). The Flower Ornament Scripture : A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sūtra, pp. 31-46. ISBN 0-87773-940-4

- ^ Takeuchi Yoshinori (editor) (1995). Buddhist Spirituality: Indian, Southeast Asian, Tibetan, and Early Chinese, p. 160. Motilal Banarsidass.

- ^ Warder, A. K. (2000). Indian Buddhism. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 402. ISBN 978-81-208-1741-8.

The title Gaṇḍavyūha is obscure, being generally interpreted as 'array of flowers', 'bouquet'. it is just possible that the rhetorical called gaṇḍa, a speech having a double meaning (understood differently by two hearers), should be thought of here.

- ^ Hsüan-hua; International Institute for the Translation of Buddhist Texts (Dharma Realm Buddhist University) (1 January 1980). Flower Adornment Sutra: Chapter 39, Entering the Dharma Realm. Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. p. xxi. ISBN 978-0-917512-68-1.

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (January 1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ^ Fontein, Jan (1967). The Pilgrimage of Sudhana: A Study of Gandavyuha Illustrations. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783111562698.

- ^ Cleary, Thomas (1993). The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra. Boston, U.S.: Shambhala. ISBN 9780877739401. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "The Ten Bhūmis | 84000 Reading Room". 84000 Translating The Words of The Budda. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- ^ "The Stem Array | 84000 Reading Room". 84000 Translating The Words of The Budda. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ^ "The Great Means Expansive Buddha Flower Adornment Sutra". THE SAGELY CITY OF TEN THOUSAND BUDDHAS. Buddhist Text Translation Society. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

Further reading

Prince, Tony (2020), Universal Enlightenment - An introduction to the Teachings and Practices of Huayen Buddhism (2nd ed.) Amazon Kindle Book, ASIN: B08C37PG7G

External links

- The Avatamsaka Sutra (the Flower Adornment Sutra) with explanation

- Introducing the Avatamsaka Sutra - an outline of the sutra by a disciple of Master Hsuan Hua

- Articles by Imre Hamar

- 大方廣佛華嚴經 Avataṃsakasūtra Chinese text with matching English vocabulary at NTI Reader digital library

- CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Articles containing Sanskrit-language text

- Articles containing Standard Tibetan-language text

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles containing Japanese-language text

- Articles containing Korean-language text

- Articles containing Vietnamese-language text

- Huayan

- Mahayana sutras

- Vaipulya sutras

- Yogacara