Double-loop learning

Double-loop learning entails the modification of goals or decision-making rules in the light of experience. The first loop uses the goals or decision-making rules, the second loop enables their modification, hence "double-loop". Double-loop learning recognises that the way a problem is defined and solved can be a source of the problem.[1] This type of learning can be useful in organizational learning since it can drive creativity and innovation, going beyond adapting to change to anticipating or being ahead of change.[2]

Concept

Double-loop learning is contrasted with "single-loop learning": the repeated attempt at the same problem, with no variation of method and without ever questioning the goal. Chris Argyris described the distinction between single-loop and double-loop learning using the following analogy:

[A] thermostat that automatically turns on the heat whenever the temperature in a room drops below 69°F is a good example of single-loop learning. A thermostat that could ask, "why am I set to 69°F?" and then explore whether or not some other temperature might more economically achieve the goal of heating the room would be engaged in double-loop learning

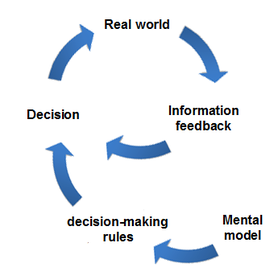

Double-loop learning is used when it is necessary to change the mental model on which a decision depends. Unlike single loops, this model includes a shift in understanding, from simple and static to broader and more dynamic, such as taking into account the changes in the surroundings and the need for expression changes in mental models.[3] It is required if the problem or mismatch that starts the organizational learning process cannot be addressed by small adjustments because it involves the organization's governing variables.[4] Organizational learning in such cases occurs when the diagnosis and intervention produce changes in the underlying policies, assumptions, and goals.[5] According to Argyris, many organizations resist double-loop learning due to a number of variables such as resistance to change, fear of failure, and overemphasis on control.[6]

- Reference models I and II

Western Approaches Tactical Unit

The Western Approaches Tactical Unit of the Royal Navy during WW2 is an example of an organization that received information and takes action, but the result is not desirable. The development of corrective measures requires an assessment of the organization's essential characteristics is double loop learning. This means that errors are detected and remedied in ways that change the organization's basic standards, policies and goals.

The Western Approaches Tactical Unit was able to develop and update anti-submarine tactical doctrine between 1942 and 1945 as new with new technology and assets became available. We were able to collect, transfer and integrate information to achieve our three goals of challenging norms, objectives and applicable policies for merchant shipping protection; promotes doctrinal innovation to counter changing German submarine tactics and technology used to attack convoys and to teach doctrine to Naval Officers appointed as North Atlantic Escorts and Royal Air Force (RAF) Coastal Commanders. [7]

Historical precursors

A Behavioral Theory of the Firm (1963) describes how organizations learn, using (what would now be described as) double-loop learning:

An organization ... changes its behavior in response to short-run feedback from the environment according to some fairly well-defined rules. It changes rules in response to longer-run feedback according to more general rules, and so on.

See also

References

- ^ a b Argyris, Chris (May 1991). "Teaching smart people how to learn" (PDF). Harvard Business Review. 69 (3): 99–109. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Malone, Samuel A. (2003). Learning about Learning. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. p. 80. ISBN 0852929897. OCLC 52879237.

- ^ Mildeova, S., Vojtko V. (2003). Systémová dynamika (in Czech). Prague: Oeconomica. pp. 19–24. ISBN 978-80-245-0626-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Horst, Hilde ter; Mulder, Martin; Sambrook, Sally; Scheerens, Jaap; Stewart, Jim; Tjepkema, Saskia, eds. (2002). HRD and Learning Organisations in Europe. Routledge studies in human resource development. Vol. 3. London; New York: Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 0415277884. OCLC 49350862.

- ^ Rahim, M. Afzalur (2001). Managing Conflict in Organizations (3 ed.). Westport, CT: Quorum Books. p. 64. ISBN 1567202624. OCLC 45791568.

- ^ Bess, James L.; Dee, Jay R. (2008). Understanding College and University Organization: Theories for Effective Policy and Practice. Vol. 2. Stylus Publishing. p. 676. ISBN 9781579227746. OCLC 73926579.

- ^ [1] The Royal Navy And Organizational Learning | The Western Approaches Tactical Unit and the Battle of the Atlantic | Geoffrey Sloan | Naval War College Review, Vol. 72 [2019], No. 4, Art. 1 | Pages 27

- ^ Cyert R.M.; March J.G. (1963). A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. pp. 101–102.

- ^ Quote taken from p. 9 of The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management (2003) which describes this quote as "an early version of the distinction between single and double-loop learning." and refers to the 1963 edition.

Further reading

- Bassot, Barbara (2015). "Bringing assumptions to the surface". The reflective practice guide: an interdisciplinary approach to critical reflection. Abingdon; New York: Routledge. pp. 79–92. ISBN 9781138784307. OCLC 898925915.

- Bochman, David J.; Kroth, Michael (2010). "Immunity to transformational learning and change". The Learning Organization. 17 (4): 328–342. doi:10.1108/09696471011043090.

- Fraser, J. Scott; Solovey, Andrew D. (2007). Second-order change in psychotherapy: the golden thread that unifies effective treatments. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN 978-1591474364. OCLC 65195322.

- Brockbank, Anne; McGill, Ian (2012) [2006]. "Single and double loop learning". Facilitating reflective learning: coaching, mentoring and supervision (2nd ed.). London; Philadelphia: Kogan Page. pp. 22–26. ISBN 9780749465070. OCLC 769289635.

- Argyris, Chris (2005). "Double-loop learning in organizations: a theory of action perspective". In Smith, Ken G.; Hitt, Michael A. (eds.). Great minds in management: the process of theory development. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 261–279. ISBN 978-0199276813. OCLC 60418039.

- Blackman, Deborah; Connelly, James; Henderson, Steven (January 2004). "Does double loop learning create reliable knowledge?". The Learning Organization. 11 (1): 11–27. doi:10.1108/09696470410515706. S2CID 144174842.

- Torbert, William R.; Cook-Greuter, Susanne R.; Fisher, Dalmar; Foldy, Erica; Gauthier, Alain; Keeley, Jackie; Rooke, David; Ross, Sara Nora; Royce, Catherine; Rudolph, Jenny (2004). Action inquiry: the secret of timely and transforming leadership. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. ISBN 978-1576752647. OCLC 53793296.

- Smith, Mark K. (2013) [2001]. "Chris Argyris: theories of action, double-loop learning and organizational learning". infed.org. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- Nielsen, Richard P. (1996). "Double-loop, dialogue methods". The politics of ethics: methods for acting, learning, and sometimes fighting with others in addressing ethics problems in organizational life. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 75–105. ISBN 978-0195096651. OCLC 34517566.

- Argyris, Chris (1999) [1993]. On organizational learning (2nd ed.). Oxford; Malden, MA: Blackwell Business. ISBN 978-0631213086. OCLC 40460132.

- Isaacs, William N. (September 1993). "Taking flight: dialogue, collective thinking, and organizational learning" (PDF). Organizational Dynamics. 22 (2): 24–39. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(93)90051-2.

- Argyris, Chris (1980). Inner contradictions of rigorous research. Organizational and occupational psychology. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0120601509. OCLC 6421943.

- Argyris, Chris; Schön, Donald A. (1978). Organizational learning: a theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0201001747. OCLC 394956102.

- Argyris, Chris (September 1976). "Single-loop and double-loop models in research on decision making". Administrative Science Quarterly. 21 (3): 363–375. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.463.4908. doi:10.2307/2391848. JSTOR 2391848.