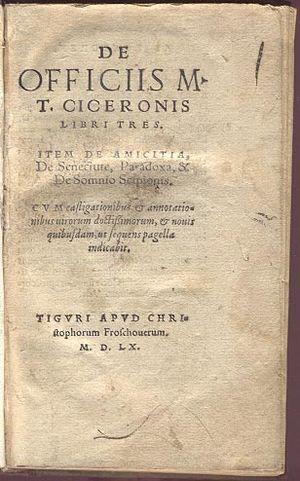

De Officiis

Title page of De officiis. Christopher Froschouer – 1560. | |

| Author | Cicero |

|---|---|

| Country | Roman Republic |

| Language | Classical Latin |

| Subject | Ethics |

| Genre | Philosophy |

Publication date | 44 BC |

Original text | De Officiis at Latin Wikisource |

De Officiis (On Duties or On Obligations) is a political and ethical treatise by the Roman orator, philosopher, and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero written in 44 BC. The treatise is divided into three books, in which Cicero expounds his conception of the best way to live, behave, and observe moral obligations. The work discusses what is honorable (Book I), what is to one's advantage (Book II), and what to do when the honorable and one's private interest apparently conflict (Book III). In the first two books Cicero was heavily influenced by the Stoic philosopher Panaetius, but wrote more independently for the third book. Though under-appreciated in modern scholarship and philosophy curriculums, De Officiis is one of the most famous philosophical works ever written. In addition to being a central component of liberal education for centuries, the work was held in high regard among many prolific philosophers and statesman including Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Hugo Grotius, Montesquieu, Voltaire, and the American Founding Fathers. De Officiis, along with Xenophon's Cyropaedia, are considered among the foundational works in the genre of the mirrors for princes, now most famously associated with Machiavelli's The Prince.

Background

De Officiis was written in October–November 44 BC, in under four weeks.[1] This was Cicero's last year alive, and he was 62 years of age. Cicero was at this time still active in politics, trying to stop revolutionary forces from taking control of the Roman Republic. Despite his efforts, the republican system failed to revive even upon the assassination of Caesar, and Cicero was himself assassinated shortly thereafter.

Writing

De Officiis is written in the form of a letter to his son Cicero Minor, who studied philosophy in Athens. Judging from its form, it is nonetheless likely that Cicero wrote with a broader audience in mind. The essay was published posthumously.

Although Cicero was influenced by the Academic, Peripatetic, and Stoic schools of Greek philosophy, this work shows the influence of the Stoic philosopher Panaetius.[2][3] Panaetius was a Greek philosopher who had resided in Rome around eighty years previously.[4] He wrote a book On Duties (Greek: Περὶ Καθήκοντος) in which he divided his subject into three parts but had left the work unfinished at the third stage.[4] Although Cicero draws from many other sources, for his first two books he follows the steps of Panaetius fairly closely.[5] The third book is more independent,[5] and Cicero disclaims having been indebted to any preceding writers on the subject.[6] Michael Grant tells us that "Cicero himself seems to have regarded this treatise as his spiritual testament and masterpiece."[7]

Cicero urged his son Marcus to follow nature and wisdom, as well as politics, and warned against pleasure and indolence. Cicero's essay relies heavily on anecdotes, much more than his other works, and is written in a more leisurely and less formal style than his other writings, perhaps because he wrote it hastily. Like the satires of Juvenal, Cicero's De Officiis refers frequently to current events of his time.

Contents

The work discusses what is honorable (Book I), what is expedient or to one's advantage (Book II), and what to do when the honorable and expedient conflict (Book III). Cicero says they are the same and that they only appear to be in conflict. In Book III, Cicero expresses his own ideas.[8]

Book One

The first book treats of what is honorable in itself.[6] He shows in what true manner our duties are founded in honor and virtue.[6] The four constituent parts of virtue are truth, justice, fortitude, and decorum, and our duties are founded in the right perception of these.[6]

1-10 INTRODUCTION

1-3 Address to Marcus

4-6 Subject of discussion to be appropriate action; a qualified Stoicism to be followed

7-8 "Entirely" appropriate actions and "ordinarily" appropriate action

9-10 A fivefold division of the subject: (1) the honorable, consisting of the virtues, and (2) the possible conflict between the virtues; (3) the useful, and (4) the possible conflict between useful things, and (5) the possible conflict between the honorable and the useful

11-14 HUMAN NATURE

11 The needs of all living beings

11-14 Virtues specific to human beings

15-17 HONORABLENESS AS CONSISTING OF TWO KINDS OF VIRTUE

15-16 Wisdom and the contemplative life

17 The remaining three virtues and the political life

18-19 WISDOM

18-19 The virtues of wisdom

19 The contemplative and political lives revisited

20-60 JUSTICE

20-41 The virtue of justice

20-23 Definition of justice

23-30 Definition of injustice

31-32 The importance of circumstance and the limitations of precepts

33-40 Precepts of justice, especially among nations

41 The way of the fox and the lion

42-49 Beneficence, the companion of justice

43 Avoid injustice

44 Give according to one's own means

45-49 Give to each according to his worth

50-60 The limitation of justice and beneficence

50-55 The natural beginnings of human association and the nature of human affection

55-60 Conflicts of obligation between associations

61-92 MAGNANIMITY

61-69 Definition of magnanimity

69-73 Comparison between contemplative and political magnanimity

73-84 Comparison between civic and martial magnanimity

85-91 Civic magnanimity

93-151 PROPRIETY

93-99 Definition of propriety

100-106 What is proper according to human nature

107-114 According to individual characteristics

115-116 According to chance and circumstance

117-121 According to one's individual judgement

122-123 What is proper according to age

124-125 What is proper according to political status

126-132 What is a proper physical and mental bearing

132-137 What is proper in speech

138-140 What is a proper use of property

141 Summary

142-151 Orderliness

152-161 CONFLICT AND COMPARISON BETWEEN THE VIRTUES

152 The possible conflict between the virtues

153-160 The conflict between wisdom and justice

157 The conflict between justice and magnanimity

159 The conflict between justice and propriety

161 Conclusion

Book Two

The second book enlarges on those duties which relate to private advantage and the improvement of life.[6] The book focuses on political advancement, and the means employed for the attainment of wealth and power.[6] The honorable means of gaining popularity include generosity, courtesy, and eloquence.[6]

Book Three

The third book discusses the choice to be made when there is an apparent conflict between virtue and expediency.[6] True virtue can never be put in competition with private advantage.[6] Thus nothing should be accounted useful or profitable if not strictly virtuous, and there ought to be no separation of the principles of virtue and expediency.[6]

Cicero proposes some rules for cases of doubt, where seeming utility comes into competition with virtue.[6] He examines in what situations one may seek private gain with honour.[6] He takes his examples from Roman history, such as the case of Marcus Atilius Regulus who was released by the Carthaginians to negotiate a peace, advised the Roman Senate to reject the proposals, and fulfilled his oath by returning to Carthage.[6]

Themes

De Officiis has been characterized as an attempt to define ideals of public behavior.[9] It criticizes the recently overthrown dictator Julius Caesar in several places, and his dictatorship as a whole. Cicero claims that the absence of political rights corrupts moral virtues. Cicero also speaks of a natural law that is said to govern both humans[10] and gods alike.[11]

Legacy

The work's legacy is profound. Although not a Christian work, St. Ambrose in 390 declared it legitimate for the Church to use (along with everything else Cicero, and the equally popular Roman philosopher Seneca, had written). It became a moral authority during the Middle Ages. Of the Church Fathers, St. Augustine, St. Jerome and even more so St. Thomas Aquinas, are known to have been familiar with it.[12] Illustrating its importance, some 700 handwritten copies remain extant in libraries around the world dating back to before the invention of the printing press. Though this does not surpass the Latin grammarian Priscian's 900 extant handwritten copies, it places De Officiis far above many classical works. Following the invention of the printing press, De Officiis was the third book to be printed—third only to the Gutenberg Bible and Donatus's "Ars Minor", which was the first printed book.[13]

Petrarch, the father of humanism and a leader in the revival of Classical learning, championed Cicero. It is suspected that Machiavelli's The Prince is at least in part meant to be a direct refutation of Cicero's De Officiis. is Several of his works build upon the precepts of De Officiis.[14] Prince Peter, Duke of Coimbra, member of the Order of the Garter, translated the treatise to portuguese in 1437, signal of the wide spread of the work in medieval courts.[15] The Catholic humanist Erasmus published his own edition in Paris in 1501. His enthusiasm for this moral treatise is expressed in many works.[14][16] The German humanist Philip Melanchthon established De Officiis in Lutheran humanist schools.[14]

T. W. Baldwin said that "in Shakespeare's day De Officiis was the pinnacle of moral philosophy".[17] Sir Thomas Elyot, in his popular Governour (1531), lists three essential texts for bringing up young gentlemen: Plato's works, Aristotle's Ethics, and De Officiis.[18]

In the 17th century it was a standard text at English schools (Westminster and Eton) and universities (Cambridge and Oxford). It was extensively discussed by Hugo Grotius and Samuel von Pufendorf.[19] Grotius drew heavily on De officiis in his major work, On the Law of War and Peace.[14] It influenced Robert Sanderson and John Locke.[19]

In the 18th century, Voltaire said of De Officiis "No one will ever write anything more wise".[20] Frederick the Great thought so highly of the book that he asked the scholar Christian Garve to do a new translation of it, even though there had been already two German translations since 1756. Garve's project resulted in 880 additional pages of commentary.

In 1885, the city of Perugia was shaken by the theft of an illuminated manuscript of De Officiis from the city's Library Augusta. The chief librarian Adamo Rossi, a well-known scholar, was originally suspected but exonerated after a lengthy administrative and judicial investigation. The culprit in the theft was never found. Suspicion fell on a janitor who a few years later became well-to-do enough to build for himself a fine house. The former janitor's house was nicknamed "Villa Cicero" by residents of Perugia.

The 2002 George Mason Memorial in Washington, D.C. includes De Officiis as an element of the statue of a seated Mason.

De Officiis continues to be one of the most popular of Cicero's works because of its style, and because of its depiction of Roman political life under the Republic.

Quotes

- ...and brave he surely cannot possibly be that counts pain the supreme evil, nor temperate he that holds pleasure to be the supreme good. (Latin: fortis vero dolorem summum malum iudicans aut temperans voluptatem summum bonum statuens esse certe nullo modo potest) (I, 5)

- Not for us alone are we born; our country, our friends, have a share in us. (Latin: non nobis solum nati sumus ortusque nostri partem patria vindicat, partem amici) (I, 22)

- Let us remember that justice must be observed even to the lowest. (Latin: Meminerimus autem etiam adversus infimos iustitiam esse servandam) (I, 41)

- Let arms yield to the toga, the laurel defer to praise. (Latin: cedant arma togae concedat laurea laudi) (I, 77)

- It is the function of justice not to do wrong to one's fellow-men; of considerateness, not to wound their feelings; and in this the essence of propriety is best seen. (Latin: Iustitiae partes sunt non violare homines, verecundiae non offendere, in quo maxime vis perspicitur decori) (I, 99)

- Is anyone unaware that Fortune plays a major role in both success and failure? (Latin: Magnam vim esse in fortuna in utramque partem, vel secundas ad res vel adversas, quis ignorat?) (II, 19)

- Of evils choose the least. (Latin: Primum, minima de malis.) (III, 102)

Citations

- ^ Marcus Tullius Cicero and P. G. Walsh. On Obligations. 2001, p. ix

- ^ Atkins & Griffin 1991, p. xix

- ^ Cicero, Miller: On Duty, iii. 23

- ^ a b Dunlop 1827, p. 257

- ^ a b Miller 1913, p. xiv

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Dunlop 1827, p. 258

- ^ Cicero, Grant: "Selected Works", p. 158

- ^ Cicero, Grant: "Selected Works", p. 157

- ^ Marcus Tullius Cicero and P. G. Walsh. On Obligations. 2001, p. xxx

- ^ Atkins & Griffin 1991, p. xxvi

- ^ Cicero, Miller: On Duty, Book III. v. 23

- ^ Hannis Taylor, Cicero: A Sketch of His Life and Works, A.C. McClurg & Co. 1916, p. 9

- ^ 'The first printed book was not Gutenberg's famed forty-two-line Bible but rather Donatus's Ars Mino, which Gutenberg, correctly sizing up the market, hoped to sell in class sets to schools.' Thus, Jürgen Leonhardt, "Latin: A World Language" (Belknap Press 2013) p. 99.

- ^ a b c d Cicero; Walsh: "On Obligations" pp. xliii–xliv

- ^ Manuel Cadafaz de Matos, "A PRESENÇA DE CÍCERO NA OBRA DE PENSADORES PORTUGUESES NOS SÉCULOS XV E XVI (1436-1543)", Humanitas 46 (1994)

- ^ Erasmus' Epistolae 152

- ^ T. W. Baldwin, "William Shakspere's Small Latine & lesse Greeke", Vol. 2, University of Illinois Press, 1944, p. 590, Available online Archived 2012-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sir Thomas Elyot, The Boke named the Governour, Vol. 1, Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co. 1883 pp. 91–94

- ^ a b John Marshall, "John Locke: Resistance, Religion, and Responsibility", Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 162, 164, 299

- ^ Voltaire, Cicero, Philosophical Dictionary Part 2 Orig. Published 1764

References

- Atkins, E. M.; Griffin, M. T. (1991), Cicero: On Duties (Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought), Cambridge University Press

- Dunlop, John (1827), History of Roman literature from its earliest period to the Augustan age, vol. 1, E. Littell

- Miller, Walter (1913), Cicero: de Officiis, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press

Further reading

- Why Cicero's De Officiis? By Ben R. Schneider, Jr. Professor Emeritus of English at Lawrence University.

- Atkins, E. M.; Cicero, Marcus Tullius; Griffin, M. T., Cicero: On Duties (Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought), Cambridge University Press (1991)

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius; Grant, Michael, "Selected Works", Penguin Classics (1960)

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius; Miller, Walter, "On Duties", Loeb Classical Library No. 30 (1913)

- Cicero; Walsh, P. G., On Obligations, Oxford University Press (2001)

- Dyck, Andrew R., A Commentary on Cicero, De Officiis, Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan Press (1996)

- Griffin, Miriam T. and Margaret E. Atkins, Cicero. On Duties, Cambridge University Press (1991)

- Nelson, N. E., Cicero's De Officiis in Christian Thought, University of Michigan Studies in Language and Literature 10 (1933)

- Newton, Benjamin Patrick, Marcus Tullius Cicero: On Duties (Agora Editions), Cornell University Press (2016)

External links

Media related to De Officiis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to De Officiis at Wikimedia Commons Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: De officiis

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: De officiis- De Officiis in Latin and English at the Perseus Project

- De Officiis – Latin with English translation by Walter Miller (1913) – Loeb Classical Library edition, Internet Archive

- De Officiis, English translation by Walter Miller (1913), LacusCurtius

- De Officiis at Project Gutenberg

De Officiis, English translation by Walter Miller public domain audiobook at LibriVox

De Officiis, English translation by Walter Miller public domain audiobook at LibriVox- De Officiis online in Latin at The Latin Library

- De Officiis – From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Articles containing Latin-language text

- Articles that link to foreign-language Wikisources

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Commons category link is the pagename

- Articles with Project Gutenberg links

- Articles with LibriVox links

- AC with 0 elements

- Philosophical works by Cicero

- 1st-century BC Latin books

- 44 BC