Civil Rights Act of 1964

Lua error in Module:Effective_protection_level at line 16: attempt to index field 'FlaggedRevs' (a nil value).

| |

| Long title | An act to enforce the constitutional right to vote, to confer jurisdiction upon the district courts of the United States of America to provide injunctive relief against discrimination in public accommodations, to authorize the Attorney General to institute suits to protect constitutional rights in public facilities and public education, to extend the Commission on Civil Rights, to prevent discrimination in federally assisted programs, to establish a Commission on Equal Employment Opportunity, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 88th United States Congress |

| Effective | July 2, 1964 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 88-352 |

| Statutes at Large | 78 Stat. 241 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | |

| Titles amended | Title 42—Public Health And Welfare |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Pub.L. 88–352, 78 Stat. 241, enacted July 2, 1964) is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex,[a] and national origin.[4] It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requirements, racial segregation in schools and public accommodations, and employment discrimination. The act "remains one of the most significant legislative achievements in American history".[5]

Initially, powers given to enforce the act were weak, but these were supplemented during later years. Congress asserted its authority to legislate under several different parts of the United States Constitution, principally its power to regulate interstate commerce under Article One (section 8), its duty to guarantee all citizens equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment, and its duty to protect voting rights under the Fifteenth Amendment.

The legislation was proposed by President John F. Kennedy in June 1963, but it was opposed by filibuster in the Senate. After Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed the bill forward. The United States House of Representatives passed the bill on February 10, 1964, and after a 54-day filibuster, it passed the United States Senate on June 19, 1964. The final vote was 290–130 in the House of Representatives and 73–27 in the Senate.[6] After the House agreed to a subsequent Senate amendment, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law by President Johnson at the White House on July 2, 1964.

Background

Reconstruction and New Deal era

In the 1883 landmark Civil Rights Cases, the United States Supreme Court had ruled that Congress did not have the power to prohibit discrimination in the private sector, thus stripping the Civil Rights Act of 1875 of much of its ability to protect civil rights.[7]

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the legal justification for voiding the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was part of a larger trend by members of the United States Supreme Court to invalidate most government regulations of the private sector, except when dealing with laws designed to protect traditional public morality.

In the 1930s, during the New Deal, the majority of the Supreme Court justices gradually shifted their legal theory to allow for greater government regulation of the private sector under the commerce clause, thus paving the way for the Federal government to enact civil rights laws prohibiting both public and private sector discrimination on the basis of the commerce clause.

Influenced in part by the "Black Cabinet" advisors and the March on Washington Movement, just before the U.S. entered World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, the first federal anti-discrimination order, and established the Fair Employment Practices Committee.[8] Roosevelt's successor, President Harry Truman, appointed the President's Committee on Civil Rights, proposed the 20th century's first comprehensive Civil Rights Act, and issued Executive Order 9980 and Executive Order 9981, providing for fair employment and desegregation throughout the federal government and the armed forces.[9]

Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957, signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on September 9, 1957, was the first federal civil rights legislation since the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to become law. After the Supreme Court ruled school segregation unconstitutional in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education, Southern Democrats began a campaign of "massive resistance" against desegregation, and even the few moderate white leaders shifted to openly racist positions.[10][11] Partly in an effort to defuse calls for more far-reaching reforms, Eisenhower proposed a civil rights bill that would increase the protection of African American voting rights.[12]

Despite having a limited impact on African-American voter participation, at a time when black voter registration was just 20%, the Civil Rights Act of 1957 did establish the United States Commission on Civil Rights and the United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. By 1960, black voting had increased by only 3%,[13] and Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1960, which eliminated certain loopholes left by the 1957 Act.

1963 Kennedy civil rights bill

In winning the 1960 United States presidential election, Kennedy took 70% of the African American vote.[14] But due to his somewhat narrow victory and Democrats' narrow majorities in Congress, he was wary to push hard for civil rights legislation for fear of losing southern support.[14] Moreover, according to the Miller Center, he wanted to wait until his second term to send Congress a civil rights bill.[15] But with elevated racial tensions and a wave of African-American protests in the spring of 1963, such as the Birmingham campaign, Kennedy realized he had to act on civil rights.[16][17]

Kennedy first proposed the 1964 bill in his Report to the American People on Civil Rights on June 11, 1963.[18] He sought legislation "giving all Americans the right to be served in facilities which are open to the public—hotels, restaurants, theaters, retail stores, and similar establishments"—as well as "greater protection for the right to vote". In late July, Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers, warned that if Congress failed to pass Kennedy's civil rights bill, the country would face another civil war.[19]

Emulating the Civil Rights Act of 1875, Kennedy's civil rights bill included provisions to ban discrimination in public accommodations and enable the U.S. Attorney General to join lawsuits against state governments that operated segregated school systems, among other provisions. But it did not include a number of provisions civil rights leaders deemed essential, including protection against police brutality, ending discrimination in private employment, and granting the Justice Department power to initiate desegregation or job discrimination lawsuits.[20]

Legislative history

House of Representatives

On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy met with Republican leaders to discuss the legislation before his television address to the nation that evening. Two days later, Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen and Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield both voiced support for the president's bill, except for provisions guaranteeing equal access to places of public accommodations. This led to several Republican Representatives drafting a compromise bill to be considered. On June 19, the president sent his bill to Congress as it was originally written, saying legislative action was "imperative".[21][22] The president's bill went first to the House of Representatives, where it was referred to the Judiciary Committee, chaired by Emanuel Celler, a Democrat from New York. After a series of hearings on the bill, Celler's committee strengthened the act, adding provisions to ban racial discrimination in employment, providing greater protection to black voters, eliminating segregation in all publicly owned facilities (not just schools), and strengthening the anti-segregation clauses regarding public facilities such as lunch counters. They also added authorization for the Attorney General to file lawsuits to protect individuals against the deprivation of any rights secured by the Constitution or U.S. law. In essence, this was the controversial "Title III" that had been removed from the 1957 Act and 1960 Act. Civil rights organizations pressed hard for this provision because it could be used to protect peaceful protesters and black voters from police brutality and suppression of free speech rights.[20]

Lobbying efforts

Lobbying support for the Civil Rights Act was coordinated by the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, a coalition of 70 liberal and labor organizations. The principal lobbyists for the Leadership Conference were civil rights lawyer Joseph L. Rauh Jr. and Clarence Mitchell Jr. of the NAACP.[23]

After the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, on August 28, 1963, the organizers visited Kennedy to discuss the civil rights bill.[24] Roy Wilkins, A. Philip Randolph, and Walter Reuther attempted to persuade him to support a provision establishing a Fair Employment Practices Commission that would ban discriminatory practices by all federal agencies, unions, and private companies.[24]

Kennedy called the congressional leaders to the White House in late October 1963 to line up the necessary votes in the House for passage.[25] The bill was reported out of the Judiciary Committee in November 1963 and referred to the Rules Committee, whose chairman, Howard W. Smith, a Democrat and staunch segregationist from Virginia, indicated his intention to keep the bill bottled up indefinitely.

Johnson's appeal to Congress

The assassination of United States President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, changed the political situation. Kennedy's successor as president, Lyndon B. Johnson, made use of his experience in legislative politics, along with the bully pulpit he wielded as president, in support of the bill. In his first address to a joint session of Congress on November 27, 1963, Johnson told the legislators, "No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long."[26]

Judiciary Committee chairman Celler filed a petition to discharge the bill from the Rules Committee;[20] it required the support of a majority of House members to move the bill to the floor. Initially, Celler had a difficult time acquiring the signatures necessary, with many Representatives who supported the civil rights bill itself remaining cautious about violating normal House procedure with the rare use of a discharge petition. By the time of the 1963 winter recess, 50 signatures were still needed.

After the return of Congress from its winter recess, however, it was apparent that public opinion in the North favored the bill and that the petition would acquire the necessary signatures. To avert the humiliation of a successful discharge petition, Chairman Smith relented and allowed the bill to pass through the Rules Committee.[20]

Passage in the Senate

Johnson, who wanted the bill passed as soon as possible, ensured that it would be quickly considered by the Senate. Normally, the bill would have been referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee, which was chaired by James O. Eastland, a Democrat from Mississippi, whose firm opposition made it seem impossible that the bill would reach the Senate floor. Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield took a novel approach to prevent the bill from being kept in limbo by the Judiciary Committee: initially waiving a second reading immediately after the first reading, which would have sent it to the Judiciary Committee, he took the unprecedented step of giving the bill a second reading on February 26, 1964, thereby bypassing the Judiciary Committee, and sending it to the Senate floor for debate immediately.

When the bill came before the full Senate for debate on March 30, 1964, the "Southern Bloc" of 18 southern Democratic Senators and lone Republican John Tower of Texas, led by Richard Russell, launched a filibuster to prevent its passage.[28] Russell proclaimed, "We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would tend to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our [Southern] states."[29][30]

Strong opposition to the bill also came from Senator Strom Thurmond, who was still a Democrat at the time: "This so-called Civil Rights Proposals [sic], which the President has sent to Capitol Hill for enactment into law, are unconstitutional, unnecessary, unwise and extend beyond the realm of reason. This is the worst civil-rights package ever presented to the Congress and is reminiscent of the Reconstruction proposals and actions of the radical Republican Congress."[31]

After the filibuster had gone on for 54 days, Senators Mansfield, Hubert Humphrey, Everett Dirksen, and Thomas Kuchel introduced a substitute bill that they hoped would overcome it by combining a sufficient number of Republicans as well as core liberal Democrats. The compromise bill was weaker than the House version as to the government's power in regulating the conduct of private business, but not weak enough to make the House reconsider it.[32]

Senator Robert Byrd ended his filibuster in opposition to the bill on the morning of June 10, 1964, after 14 hours and 13 minutes. Up to then, the measure had occupied the Senate for 60 working days, including six Saturdays. The day before, Democratic Whip Hubert Humphrey, the bill's manager, concluded that he had the 67 votes required at that time to end the debate and the filibuster. With six wavering senators providing a four-vote victory margin, the final tally stood at 71 to 29. Never before in its entire history had the Senate been able to muster enough votes to defeat a filibuster on a civil rights bill, and only once in the 37 years since 1927 had it agreed to cloture for any measure.[33]

The most dramatic moment during the cloture vote came when Senator Clair Engle was wheeled into the chamber. Suffering from terminal brain cancer, unable to speak, he pointed to his left eye, signifying his affirmative "Aye" vote when his name was called. He died seven weeks later.

Final Passage

On June 19, the compromise bill passed the Senate by a vote of 73–27, quickly passed through the conference committee, which adopted the Senate version of the bill, then was passed by both houses of Congress and signed into law by Johnson on July 2, 1964.[34]

Vote totals

Totals are in Yea–Nay format:

- The original House version: 290–130 (69–31%)[1]

- Cloture in the Senate: 71–29

- The Senate version: 73–27[2]

- The Senate version, as voted on by the House: 289–126 (70–30%)[3]

By party

The original House version:[1]

- Democratic Party: 152–96 (61–39%)

- Republican Party: 138–34 (80–20%)

Cloture in the Senate:[35]

- Democratic Party: 44–23 (66–34%)

- Republican Party: 27–6 (82–18%)

The Senate version:[2]

- Democratic Party: 46–21 (69–31%)

- Republican Party: 27–6 (82–18%)

The Senate version, voted on by the House:[3]

- Democratic Party: 153–91 (63–37%)

- Republican Party: 136–35 (80–20%)

By region

Note that "Southern", as used here, refers to members of Congress from the eleven states that had made up the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War. "Northern" refers to members from the other 39 states, regardless of the geographic location of those states.[36]

The House of Representatives:[3]

- Northern: 281–32 (90–10%)

- Southern: 8–94 (8–92%)

The Senate:[2]

- Northern: 72–6 (92–8%)

- Southern: 1–21 (5–95%) – Ralph Yarborough of Texas was the only Southerner to vote in favor in the Senate

By party and region

The House of Representatives:[3]

- Southern Democrats: 8–83 (9–91%) – four Representatives from Texas (Jack Brooks, Albert Thomas, J. J. Pickle, and Henry González), two from Tennessee (Richard Fulton and Ross Bass), Claude Pepper of Florida and Charles L. Weltner of Georgia voted in favor

- Southern Republicans: 0–11 (0–100%)

- Northern Democrats: 145–8 (95–5%)

- Northern Republicans: 136–24 (85–15%)

Note that four Representatives voted Present while 13 did not vote.

The Senate:[2]

- Southern Democrats: 1–20 (5–95%) – only Ralph Yarborough of Texas voted in favor

- Southern Republicans: 0–1 (0–100%) – John Tower of Texas, the only Southern Republican at the time, voted against

- Northern Democrats: 45–1 (98–2%) – only Robert Byrd of West Virginia voted against

- Northern Republicans: 27–5 (84–16%) – Norris Cotton (NH), Barry Goldwater (AZ), Bourke Hickenlooper (IA), Edwin Mecham (NM), and Milward Simpson (WY) voted against

Aspects

Women's rights

Just one year earlier, the same Congress had passed the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which prohibited wage differentials based on sex. The prohibition on sex discrimination was added to the Civil Rights Act by Howard W. Smith, a powerful Virginia Democrat who chaired the House Rules Committee and who strongly opposed the legislation. Smith's amendment was passed by a teller vote of 168 to 133. Historians debate Smith's motivation, whether it was a cynical attempt to defeat the bill by someone opposed to civil rights both for blacks and women, or an attempt to support their rights by broadening the bill to include women.[38][39][40][41] Smith expected that Republicans, who had included equal rights for women in their party's platform since 1944,[42] would probably vote for the amendment. Historians speculate that Smith was trying to embarrass northern Democrats who opposed civil rights for women because the clause was opposed by labor unions. Representative Carl Elliott of Alabama later claimed "Smith didn't give a damn about women's rights", as "he was trying to knock off votes either then or down the line because there was always a hard core of men who didn't favor women's rights",[43] and the Congressional Record records that Smith was greeted by laughter when he introduced the amendment.[44]

Smith asserted that he was not joking and he sincerely supported the amendment. Along with Representative Martha Griffiths,[45] he was the chief spokesperson for the amendment.[44] For twenty years, Smith had sponsored the Equal Rights Amendment (with no linkage to racial issues) in the House because he believed in it. He for decades had been close to the National Woman's Party and its leader Alice Paul, who had been a leading figure in winning the right to vote for women in 1920, was co-author of the first Equal Rights Amendment, and a chief supporter of equal rights proposals since then. She and other feminists had worked with Smith since 1945 trying to find a way to include sex as a protected civil rights category and felt now was the moment.[46] Griffiths argued that the new law would protect black women but not white women, and that was unfair to white women. Black feminist lawyer Pauli Murray wrote a supportive memorandum at the behest of the National Federation of Business and Professional Women.[47] Griffiths also argued that the laws "protecting" women from unpleasant jobs were actually designed to enable men to monopolize those jobs, and that was unfair to women who were not allowed to try out for those jobs.[48] The amendment passed with the votes of Republicans and Southern Democrats. The final law passed with the votes of Republicans and Northern Democrats. Thus, as Justice William Rehnquist explained in Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, "The prohibition against discrimination based on sex was added to Title VII at the last minute on the floor of the House of Representatives [...] the bill quickly passed as amended, and we are left with little legislative history to guide us in interpreting the Act's prohibition against discrimination based on 'sex.'"[49]

Desegregation

One of the most damaging arguments by the bill's opponents was that once passed, the bill would require forced busing to achieve certain racial quotas in schools.[50] Proponents of the bill, such as Emanuel Celler and Jacob Javits, said that the bill would not authorize such measures. Leading sponsor Senator Hubert Humphrey (D-MN) wrote two amendments specifically designed to outlaw busing.[50] Humphrey said, "if the bill were to compel it, it would be a violation [of the Constitution], because it would be handling the matter on the basis of race and we would be transporting children because of race."[50] While Javits said any government official who sought to use the bill for busing purposes "would be making a fool of himself," two years later the Department of Health, Education and Welfare said that Southern school districts would be required to meet mathematical ratios of students by busing.[50]

Aftermath

Political repercussions

The bill divided both major American political parties and engendered a long-term change in the demographics of the support for each. President Kennedy realized that supporting this bill would risk losing the South's overwhelming support of the Democratic Party. Both Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and Vice President Johnson had pushed for the introduction of the civil rights legislation. Johnson told Kennedy aide Ted Sorensen that "I know the risks are great and we might lose the South, but those sorts of states may be lost anyway."[51] Senator Richard Russell, Jr. later warned President Johnson that his strong support for the civil rights bill "will not only cost you the South, it will cost you the election".[52] Johnson, however, went on to win the 1964 election by one of the biggest landslides in American history. The South, which had five states swing Republican in 1964, became a stronghold of the Republican Party by the 1990s.[53]

Although majorities in both parties voted for the bill, there were notable exceptions. Though he opposed forced segregation,[54] Republican 1964 presidential candidate, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, voted against the bill, remarking, "You can't legislate morality." Goldwater had supported previous attempts to pass civil rights legislation in 1957 and 1960 as well as the 24th Amendment outlawing the poll tax. He stated that the reason for his opposition to the 1964 bill was Title II, which in his opinion violated individual liberty and states' rights. Democrats and Republicans from the Southern states opposed the bill and led an unsuccessful 60 working day filibuster, including Senators Albert Gore, Sr. (D-TN) and J. William Fulbright (D-AR), as well as Senator Robert Byrd (D-WV), who personally filibustered for 14 hours straight.[55]

Continued resistance

There were white business owners who claimed that Congress did not have the constitutional authority to ban segregation in public accommodations. For example, Moreton Rolleston, the owner of a motel in Atlanta, Georgia, said he should not be forced to serve black travelers, saying, "the fundamental question [...] is whether or not Congress has the power to take away the liberty of an individual to run his business as he sees fit in the selection and choice of his customers".[56] Rolleston claimed that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a breach of the Fourteenth Amendment and also violated the Fifth and Thirteenth Amendments by depriving him of "liberty and property without due process".[56] In Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States (1964), the Supreme Court held that Congress drew its authority from the Constitution's Commerce Clause, rejecting Rolleston's claims.

Resistance to the public accommodation clause continued for years on the ground, especially in the South.[57] When local college students in Orangeburg, South Carolina, attempted to desegregate a bowling alley in 1968, they were violently attacked, leading to rioting and what became known as the "Orangeburg massacre."[58] Resistance by school boards continued into the next decade, with the most significant declines in black-white school segregation only occurring at the end of the 1960s and the start of the 1970s in the aftermath of the Green v. County School Board of New Kent County (1968) court decision.[59]

Later impact on LGBT rights

In June 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in three cases (Bostock v. Clayton County, Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda, and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which barred employers from discriminating on the basis of sex, also barred employers from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.[60] Afterward, USA Today stated that in addition to LGBTQ employment discrimination, "[t]he court's ruling is likely to have a sweeping impact on federal civil rights laws barring sex discrimination in education, health care, housing and financial credit."[61] On June 23, 2020, Queer Eye actors Jonathan Van Ness and Bobby Berk praised the Civil Rights Act rulings, which Van Ness called "a great step in the right direction".[62] Both of them still urged the United States Congress to pass the proposed Equality Act, which Berk claimed would amend the Civil Rights Act so it "would really extend healthcare and housing rights".[62]

Titles

Title I—voting rights

This title barred unequal application of voter registration requirements. Title I did not eliminate literacy tests, which acted as one barrier for black voters, other racial minorities, and poor whites in the South or address economic retaliation, police repression, or physical violence against nonwhite voters. While the Act did require that voting rules and procedures be applied equally to all races, it did not abolish the concept of voter "qualification". It accepted the idea that citizens do not have an automatic right to vote but would have to meet standards beyond citizenship.[63][64][65] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 directly addressed and eliminated most voting qualifications beyond citizenship.[63]

Title II—public accommodations

Outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin in hotels, motels, restaurants, theaters, and all other public accommodations engaged in interstate commerce; the Title defined "public accommodations" as establishments that serve the public. It exempted private clubs, without defining the term "private", or other establishments not open to the public.[66]

Title III—desegregation of public facilities

Prohibited state and municipal governments from denying access to public facilities on grounds of race, color, religion, or national origin.

Title IV—desegregation of public education

Enforced the desegregation of public schools and authorized the U.S. Attorney General to file suits to enforce said act.

Title V—Commission on Civil Rights

Expanded the Civil Rights Commission established by the earlier Civil Rights Act of 1957 with additional powers, rules, and procedures.

Title VI—nondiscrimination in federally assisted programs

Prevents discrimination by programs and activities that receive federal funds. If a recipient of federal funds is found in violation of Title VI, that recipient may lose its federal funding.

General

This title declares it to be the policy of the United States that discrimination on the ground of race, color, or national origin shall not occur in connection with programs and activities receiving Federal financial assistance and authorizes and directs the appropriate Federal departments and agencies to take action to carry out this policy. This title is not intended to apply to foreign assistance programs. Section 601 – This section states the general principle that no person in the United States shall be excluded from participation in or otherwise discriminated against on the ground of race, color, or national origin under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

Section 602 directs each Federal agency administering a program of Federal financial assistance by way of grant, contract, or loan to take action pursuant to rule, regulation, or order of general applicability to effectuate the principle of section 601 in a manner consistent with the achievement of the objectives of the statute authorizing the assistance. In seeking the effect compliance with its requirements imposed under this section, an agency is authorized to terminate or to refuse to grant or to continue assistance under a program to any recipient as to whom there has been an express finding pursuant to a hearing of a failure to comply with the requirements under that program, and it may also employ any other means authorized by law. However, each agency is directed first to seek compliance with its requirements by voluntary means.

Section 603 provides that any agency action taken pursuant to section 602 shall be subject to such judicial review as would be available for similar actions by that agency on other grounds. Where the agency action consists of terminating or refusing to grant or to continue financial assistance because of a finding of a failure of the recipient to comply with the agency's requirements imposed under section 602, and the agency action would not otherwise be subject to judicial review under existing law, judicial review shall nevertheless be available to any person aggrieved as provided in section 10 of the Administrative Procedure Act (5 U.S.C. § 1009). The section also states explicitly that in the latter situation such agency action shall not be deemed committed to unreviewable agency discretion within the meaning of section 10. The purpose of this provision is to obviate the possible argument that although section 603 provides for review in accordance with section 10, section 10 itself has an exception for action "committed to agency discretion," which might otherwise be carried over into section 603. It is not the purpose of this provision of section 603, however, otherwise to alter the scope of judicial review as presently provided in section 10(e) of the Administrative Procedure Act.

Executive Order

The December 11, 2019 executive order on combating antisemitism states: "While Title VI does not cover discrimination based on religion, individuals who face discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin do not lose protection under Title VI for also being a member of a group that shares common religious practices. Discrimination against Jews may give rise to a Title VI violation when the discrimination is based on an individual’s race, color, or national origin. It shall be the policy of the executive branch to enforce Title VI against prohibited forms of discrimination rooted in antisemitism as vigorously as against all other forms of discrimination prohibited by Title VI." The order specifies that agencies responsible for Title VI enforcement shall "consider" the (non-legally binding) working definition of antisemitism adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) on May 26, 2016, as well as the IHRA list of Contemporary Examples of Anti-Semitism, "to the extent that any examples might be useful as evidence of discriminatory intent".[67]

Title VII—equal employment opportunity

Title VII of the Act, codified as Subchapter VI of Chapter 21 of title 42 of the United States Code, prohibits discrimination by covered employers on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin (see 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2[68]). Title VII applies to and covers an employer "who has fifteen (15) or more employees for each working day in each of twenty or more calendar weeks in the current or preceding calendar year" as written in the Definitions section under 42 U.S.C. §2000e(b). Title VII also prohibits discrimination against an individual because of their association with another individual of a particular race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, such as by an interracial marriage.[69] The EEO Title VII has also been supplemented with legislation prohibiting pregnancy, age, and disability discrimination (see Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, Age Discrimination in Employment Act,[70] Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990).

In very narrowly defined situations, an employer is permitted to discriminate on the basis of a protected trait if the trait is a bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ) reasonably necessary to the normal operation of that particular business or enterprise. To make a BFOQ defense, an employer must prove three elements: a direct relationship between the trait and the ability to perform the job; the BFOQ's relation to the "essence" or "central mission of the employer's business", and that there is no less restrictive or reasonable alternative (United Automobile Workers v. Johnson Controls, Inc., 499 U.S. 187 (1991) 111 S.Ct. 1196). BFOQ is an extremely narrow exception to the general prohibition of discrimination based on protected traits (Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) 97 S.Ct. 2720). An employer or customer's preference for an individual of a particular religion is not sufficient to establish a BFOQ (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Kamehameha School—Bishop Estate, 990 F.2d 458 (9th Cir. 1993)).[71]

Title VII allows any employer, labor organization, joint labor-management committee, or employment agency to bypass the "unlawful employment practice" for any person involved with the Communist Party of the United States or of any other organization required to register as a Communist-action or Communist-front organization by final order of the Subversive Activities Control Board pursuant to the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950.[72]

There are partial and whole exceptions to Title VII for four types of employers:

- Federal government; (the proscriptions against employment discrimination under Title VII are now applicable to certain federal government offices under 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-16)

- Federally recognized Native American tribes;[73]

- Religious groups performing work connected to the group's activities, including associated education institutions;

- Bona fide nonprofit private membership organizations

The Bennett Amendment is a U.S. labor law provision in Title VII that limits sex discrimination claims regarding pay to the rules in the Equal Pay Act of 1963. It says an employer can "differentiate upon the basis of sex" when it compensates employees "if such differentiation is authorized by" the Equal Pay Act.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), as well as certain state fair employment practices agencies (FEPAs), enforce Title VII (see 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-4).[68] The EEOC and state FEPAs investigate, mediate, and may file lawsuits on employees' behalf. Where a state law contradicts federal law, it is overridden.[74] Every state except Arkansas and Mississippi maintains a state FEPA (see EEOC and state FEPA directory ). Title VII also provides that an individual can bring a private lawsuit. They must file a complaint of discrimination with the EEOC within 180 days of learning of the discrimination or they may lose the right to file suit. Title VII applies only to employers who employ 15 or more employees for 20 or more weeks in the current or preceding calendar year (42 U.S.C. § 2000e#b).

Administrative precedents

In 2012, the EEOC ruled that employment discrimination on the basis of gender identity or transgender status is prohibited under Title VII. The decision held that discrimination on the basis of gender identity qualified as discrimination on the basis of sex whether the discrimination was due to sex stereotyping, discomfort with a transition, or discrimination due to a perceived change in the individual's sex.[75][76] In 2014, the EEOC initiated two lawsuits against private companies for discrimination on the basis of gender identity, with additional litigation under consideration.[77] As of November 2014[update], Commissioner Chai Feldblum is making an active effort to increase awareness of Title VII remedies for individuals discriminated against on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.[78][79][needs update]

On December 15, 2014, under a memorandum issued by Attorney General Eric Holder, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) took a position aligned with the EEOC's, namely that the prohibition of sex discrimination under Title VII encompassed the prohibition of discrimination based on gender identity or transgender status. DOJ had already stopped opposing claims of discrimination brought by federal transgender employees.[80] The EEOC in 2015 reissued another non-binding memo, reaffirming its stance that sexual orientation was protected under Title VII.[81]

In October 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions withdrew the Holder memorandum.[82] According to a copy of Sessions' directive reviewed by BuzzFeed News, he stated that Title VII should be narrowly interpreted to cover discrimination between "men and women". Sessions stated that as a matter of law, "Title VII does not prohibit discrimination based on gender identity per se."[83] Devin O'Malley, on behalf of the DOJ, said, "the last administration abandoned that fundamental principle [that the Department of Justice cannot expand the law beyond what Congress has provided], which necessitated today's action." Sharon McGowan, a lawyer with Lambda Legal who previously served in the Civil Rights division of DOJ, rejected that argument, saying "[T]his memo is not actually a reflection of the law as it is—it's a reflection of what the DOJ wishes the law were" and "The Justice Department is actually getting back in the business of making anti-transgender law in court."[82] But the EEOC did not change its stance, putting it at odds with the DOJ in certain cases.[81]

Title VIII—registration and voting statistics

Required compilation of voter-registration and voting data in geographic areas specified by the Commission on Civil Rights.

Title IX—intervention and removal of cases

Title IX made it easier to move civil rights cases from U.S. state courts to federal court. This was of crucial importance to civil rights activists[who?] who contended that they could not get fair trials in state courts.[citation needed]

Title X—Community Relations Service

Established the Community Relations Service, tasked with assisting in community disputes involving claims of discrimination.

Title XI—miscellaneous

Title XI gives a defendant accused of certain categories of criminal contempt in a matter arising under title II, III, IV, V, VI, or VII of the Act the right to a jury trial. If convicted, the defendant can be fined an amount not to exceed $1,000 or imprisoned for not more than six months.

Major amendments

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972

Between 1965 and 1972, Title VII lacked any strong enforcement provisions. Instead, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was authorized only to investigate external claims of discrimination. The EEOC could then refer cases to the Justice Department for litigation if reasonable cause was found. The EEOC documented the nature and magnitude of discriminatory employment practices, the first study of this kind done.

In 1972, Congress passed the Equal Employment Opportunity Act.[84] The Act amended Title VII and gave EEOC authority to initiate its own enforcement litigation. The EEOC now played a major role in guiding judicial interpretations of civil rights legislation.[85]

United States Supreme Court cases

Title II case law

Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964)

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, the Supreme Court upheld the law's application to the private sector, on the grounds that Congress has the power to regulate commerce between the States. The landmark case Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States established the law's constitutionality, but did not settle all the legal questions surrounding it.

Katzenbach v. McClung (1964)

United States v. Johnson (1968)

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc. (1968)

Daniel v. Paul (1969)

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green (1973)

Title VI case law

Lau v. Nichols (1974)

In the 1974 case Lau v. Nichols, the Supreme Court ruled that the San Francisco school district was violating non-English speaking students' rights under the 1964 act by placing them in regular classes rather than providing some sort of accommodation for them.[86]

Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke (1978)

Alexander v. Sandoval (2001)

Title VII case law

Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971)

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp. (1971)

In Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., a 1971 Supreme Court case about the Act's gender provisions, the Court ruled that a company could not discriminate against a potential female employee because she had a preschool-age child unless it did the same with potential male employees.[41] A federal court overruled an Ohio state law that barred women from obtaining jobs that required the ability to lift 25 pounds and required women but not men to take lunch breaks.[41] In Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations, the Supreme Court decided that printing separate job listings for men and women is illegal, ending that practice at the country's newspapers. The United States Civil Service Commission ended the practice of designating federal jobs "women only" or "men only."[41]

Washington v. Davis (1976)

TWA v. Hardison (1977)

Dothard v. Rawlinson (1977)

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1978)

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (1986)

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57 (1986) determined that sexual harassment is considered discrimination based on sex.[87]

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989)

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) established that discrimination related to non-conformity of gender stereotypical behavior is unallowable under Title VII.

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio (1989)

United Automobile Workers v. Johnson Controls, Inc. (1991)

Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services (1998)

Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., 523 U.S. 75 (1998) further ruled that same-sex harassment is discrimination under Title VII.

Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway Co. v. White (2006)

Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. (2007)

Ricci v. DeStefano (2009)

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar (2013)

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores (2015)

Green v. Brennan (2016)

Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) and Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda (2020)

On June 15, 2020, in Bostock v. Clayton County, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that Title VII protections against workplace discrimination on the basis of sex apply to discrimination against LGBT individuals.[88] In the opinion, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that a business that discriminates against homosexual or transgender individuals is discriminating "for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex." Thus discrimination against homosexual and transgender employees is a form of sex discrimination, which is forbidden under Title VII.[89]

Bostock was consolidated with Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda.[90] Before the Supreme Court's intervention, there was a split in the circuit courts, including these two cases[91][92] as well as Evans v. Georgia Regional Hospital in the Eleventh Circuit.[93]

R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2020)

R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission determined that Title VII covers gender identity, including transgender status.[91][90]

Influence

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990—which has been called "the most important piece of federal legislation since the Civil Rights Act of 1964"—was influenced both by the structure and substance of the previous Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act was arguably of equal importance, and "draws substantially from the structure of that landmark legislation [Civil Rights Act of 1964]". The Americans with Disabilities Act paralleled its landmark predecessor structurally, drawing upon many of the same titles and statutes. For example, "Title I of the ADA, which bans employment discrimination by private employers on the basis of disability, parallels Title VII of the Act". Similarly, Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act, "which proscribes discrimination on the basis of disability in public accommodations, tracks Title II of the 1964 Act while expanding upon the list of public accommodations covered." The Americans with Disabilities Act extended "the principle of nondiscrimination to people with disabilities",[94] an idea unsought in the United States before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Act also influenced later civil rights legislation, such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968, aiding not only African Americans, but also women.

See also

- Affirmative action in the United States

- Bennett Amendment

- Bourke B. Hickenlooper

- Civil Rights Movement

- Post–civil rights era in African-American history

- The Negro Motorist Green Book

Other civil rights legislation

Notes

- ^ Three Supreme Court rulings in June 2020 confirmed that employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity is a form of discrimination on the basis of sex and is therefore also outlawed by the Civil Rights Act. See Bostock v. Clayton County, and also see below for more details.

References

- ^ a b c d "H.R. 7152. Passage". GovTrack.us. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "HR. 7152. Passage". GovTrack.us. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "H.R. 7152. Civil Rights Act of 1964. Adoption of a Resolution (H. RES. 789) Providing for House Approval of the Bill As Amended by the Senate". GovTrack.us. Archived from the original on September 10, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "Transcript of Civil Rights Act (1964)" Archived April 18, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Landmark Legislation: The Civil Rights Act of 1964". www.senate.gov. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ "HR. 7152. Passage. -- Senate Vote #409 -- Jun 19, 1964". GovTrack.us. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- ^ "The Civil Rights Act of March 1, 1875" Archived February 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, www.gmu.edu.

- ^ "FDR on racial discrimination, 1942". www.gilderlehrman.org. Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Jennifer; Hussey, Michael (May 19, 2014). "Executive Orders 9980 and 9981: Ending segregation in the Armed Forces and the Federal workforce – Pieces of History". National Archives. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ "Gillman on Klarman, 'From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality' | H-Law | H-Ne t". networks.h-net.org. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ "Racism to Redemption". National Endowment for the Humanities. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ Pach, Chester J.; Richardson, Elmo (1991). The Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower (Revised ed.). University Press of Kansas. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-7006-0437-1.

- ^ James A. Miller, "An inside look at Eisenhower's civil rights record" Archived 2012-01-07 at the Wayback Machine The Boston Globe at boston.com, 21 November 2007, accessed 28 October 2011

- ^ a b "Civil Rights Movement (The Election of 1960)". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "The Civil Rights Act of 1964 | Miller Center". Miller Center. December 27, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ "The Kennedys and the Civil Rights Movement (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ "American Experience.Eyes on the Prize.Transcript | PBS". PBS. March 26, 2017. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Radio and television address on civil rights, 11 June 1963". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. June 11, 1963. Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ Gold, Susan Dudley (2011). The Civil Rights Act of 1964. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 64, 129. ISBN 978-1-60870-040-0. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Civil Rights Movement History 1964 Jan-June: Civil Rights Bill Passes in the House (Feb)". Civil Rights Movement Archive. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Loevy, Robert (1997), The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Law that Ended Racial Segregation, State University of New York Press, p. 171. ISBN 0-7914-3362-5

- ^ Golway, Terry and Krantz, Les (2010), JFK: Day by Day, Running Press, p. 284. ISBN 978-0-7624-3742-9

- ^ "History of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights & The Leadership Conference Education Fund – The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights". Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Roy; Mitchell, Clarence; King, Martin Luther Jr; Lewis, John; Humphrey, Hubert; Parks, Gordon; Ellison, Ralph; Rustin, Bayard; Warren, Earl (October 10, 2014). "Civil Rights Era (1950–1963) - The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 9, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Reeves, Richard (1993), President Kennedy: Profile of Power, pp. 628–631

- ^ "1963 Year In Review: Transition to Johnson". UPI. Archived from the original on April 29, 2020.

- ^ Cone, James H. (1991). Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare. p. 2. ISBN 0-88344-721-5.

- ^ "A Case History: The 1964 Civil Rights Act". The Dirksen Congressional Center. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- ^ Napolitano, Andrew P. (2009). Dred Scott's Revenge: A Legal History of Race and Freedom in America. Thomas Nelson. p. 188. ISBN 9781595552655. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Remnick, Noah (June 28, 2014). "The Civil Rights Act: What JFK, LBJ, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X had to say". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ 1963 Year In Review – Part 1 – Civil Rights Bill Archived May 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine United Press International, 1963

- ^ Civil Rights Act – Battle in the Senate Archived December 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine ~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

- ^ Civil Rights Filibuster Ended Archived December 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine – United States Senate

- ^ Dallek, Robert (2004), Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President, p. 169

- ^ Jeong, Gyung-Ho; Miller, Gary J.; Sened, Itai (March 14, 2009). Closing The Deal: Negotiating Civil Rights Legislation. 67th Annual Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association. p. 29. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- ^ "Were Republicans Really..?". The Guardian. August 28, 2013. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

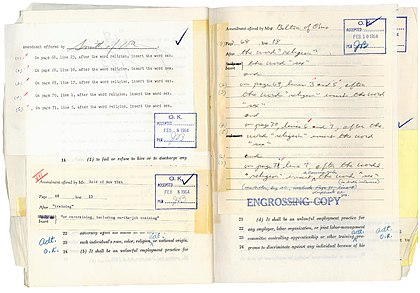

- ^ U.S. House of Representatives. Office of the Clerk of the House (September 25, 1964). Excerpt of the Engrossing Copy of H.R. 7152, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Showing Amendments. Series: General Records, 1789–2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2017 – via US National Archives Research Catalog.

- ^ Freeman, Jo. "How 'Sex' Got Into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as a Maker of Public Policy," Law and Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice, Vol. 9, No. 2, March 1991, pp 163–184. online version Archived April 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rosenberg, Rosalind (2008), Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century, pp. 187–88

- ^ Gittinger, Ted and Fisher, Allen, LBJ Champions the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Part 2 Archived August 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Prologue Magazine, The National Archives, Summer 2004, Vol. 36, No. 2 ("Certainly Smith hoped that such a divisive issue would torpedo the civil rights bill, if not in the House, then in the Senate.")

- ^ a b c d Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. pp. 245–246, 249. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ^ "The American Presidency Project". Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ^ Dierenfield, Bruce J (1981). "Conservative Outrage: the Defeat in 1966 of Representative Howard W. Smith of Virginia". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 89 (2): 194.

- ^ a b Gold, Michael Evan. A Tale of Two Amendments: The Reasons Congress Added Sex to Title VII and Their Implication for the Issue of Comparable Worth. Faculty Publications — Collective Bargaining, Labor Law, and Labor History. Cornell, 1981 [1] Archived September 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Olson, Lynne (2001), Freedom's Daughters: The Unsung Heroines of the Civil Rights Movement, p. 360

- ^ Rosenberg, Rosalind (2008), Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century, p. 187 notes that Smith had been working for years with two Virginia feminists on the issue.

- ^ Freeman, Jo (March 1991). "How 'Sex' Got into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as a Maker of Public Policy". Law and Inequality. 9 (2): 163–184. Archived from the original on April 23, 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2006.

- ^ Harrison, Cynthia (1989), On Account of Sex: The Politics of Women's Issues, 1945–1968, p. 179

- ^ (477 U.S. 57, 63–64)

- ^ a b c d Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. pp. 251–252. ISBN 9780465041954.

- ^ Kotz, Nick (2005), Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws that Changed America, p. 61.

- ^ Branch, Taylor (1998), Pillar of Fire, p. 187.

- ^ Brownstein, Ronald (May 23, 2009). "For GOP, A Southern Exposure". National Journal. Archived from the original on May 24, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- ^ Sherrill, Robert (May 25, 2001). "Conservatism as Phoenix". The Nation. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Civil Rights Filibuster Ended". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Sandoval-Strausz, A.K. (Spring 2005). "Travelers, Strangers, and Jim Crow: Law, Public Accommodations, and Civil Rights in America". Law and History Review. 23 (1): 53–94. doi:10.1017/s0738248000000055. JSTOR 30042844.

- ^ Taylor, Alan. "1964: Civil Rights Battles". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ Wolcott, Victoria W. (August 16, 2012). Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in America. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812207590. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Reardon, Sean F.; Owens, Ann (August 1, 2014). "60 Years After Brown: Trends and Consequences of School Segregation". Annual Review of Sociology. 40 (40): 199. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043152. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020 – via cepa.stanford.edu.

- ^ "Justices rule LGBT people protected from job discrimination". Arkansas Online. June 15, 2020. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Wolf, Richard (June 15, 2020). "Supreme Court grants federal job protections to gay, lesbian, transgender workers". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Martin, Annie (June 24, 2020). "'Queer Eye' stars say Supreme Court LGBTQ ruling is 'step in right direction'". United Press International. Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Civil Rights Movement History 1964 July-Dec. Here: Sections "Civil Rights Act of 1964 Signed into Law (July)" and "Effects of the Civil Rights Act"". Civil Rights Movement Archive - SNCC, SCLC, CORE, NAACP. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- ^ "Civil Rights Movement History 1964 Jan-June. Here: Sections "Civil Rights Bill Passes in the House (Feb)" and "Civil Rights Bill — Battle in the Senate (March-June)"". Civil Rights Movement Archive - SNCC, SCLC, CORE, NAACP. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- ^ "Major Features of the Civil Rights Act of 1964". CongressLink. The Dirksen Congressional Center. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ "Civil Rights Act of 1964 Title II". Wake Forest University. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ "Executive Order on Combating Anti-Semitism". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via National Archives.

- ^ a b "Civil Rights Act of 1964 – CRA – Title VII – Equal Employment Opportunities – 42 US Code Chapter 21". finduslaw. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ Parr v. Woodmen of the World Life Insurance Company, 791 F.2d 888 (11th Cir. 1986).

- ^ "Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967". Finduslaw.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ "Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Plaintiff-appellant, v. Kamehameha Schools/bishop Estate". Justia. May 10, 1993. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ "H.R. 7152--16". Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ Fields, C. K., & Cheeseman, H. R., Contemporary Employment Law (New York: Wolters Kluwer, 2017), p. 197 Archived March 30, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration. (1999) "Chapter 2: Laws and Regulations with Implications for Assessments". [2] Archived November 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Macy v. Holder Archived December 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, EEOC Appeal No. 0120120821 (April 20, 2012)

- ^ Quinones, Sam (April 25, 2012). "EEOC rules job protections also apply to transgender people". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ Rosenberg, Mica (September 9, 2014). "U.S. government lawsuits target transgender discrimination in workplace". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "What You Should Know about EEOC and the Enforcement Protections for LGBT Workers". Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ^ Feldblum, Chai [@chaifeldblum] (November 6, 2014). "ICYMI-- EEOC helping LGBT people get protection from discrimination under sex discrimination laws" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Geidner, Chris (December 18, 2014). "Justice Department Will Now Support Transgender Discrimination Claims In Litigation". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ a b "Justice Department Says Rights Law Doesn't Protect Gays". The New York Times. July 27, 2017. Archived from the original on April 29, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Holden, Dominic (October 5, 2017). "Jeff Sessions Just Reversed A Policy That Protects Transgender Workers From Discrimination". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Goico, Allison L.; Geller, Hayley (October 6, 2017). "US Attorney General Jefferson Sessions Issues New Guidance On Transgender Employees". The National Law Review. Dinsmore & Shohl LLP. Archived from the original on October 16, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Milestones In The History of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission: 1972 Archived November 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Accessed July 1, 2014

- ^ "Equal Employment Opportunity Commission". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. p. 270. ISBN 9780465041954.

- ^ Cochran, Augustus B. (2004). Sexual Harassment and the Law: the Mechelle Vinson Case. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700613234. OCLC 53284947.

- ^ "Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U.S. ___ (2020)". Justia Law. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 15, 2020). "Civil Rights Law Protects Gay and Transgender Workers, Supreme Court Rules". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Williams, Pete (June 15, 2020). "Supreme Court rules existing civil rights law protects gay and lesbian workers". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Chappell, Bill (April 22, 2019). "Supreme Court Will Hear Cases On LGBTQ Discrimination Protections For Employees". NPR. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ Higgens, Tucker (October 8, 2019). "Supreme Court clashes over meaning of 'sex' in LGBT discrimination cases". CNBC. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ Chung, Andrew (December 11, 2017). "U.S. high court turns away dispute over gay worker protections". Reuters. Reuters. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Dinerstein, Robert D. (Summer 2004). "The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990: Progeny of the Civil Rights Act of 1964". Human Rights. American Bar Association. 31 (3): 10–11. ISSN 0046-8185. JSTOR 27880436.

Bibliography

- Branch, Taylor (1998), Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–65, New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Freeman, Jo. "How 'Sex' Got Into Title VII: Persistent Opportunism as a Maker of Public Policy" Law and Inequality: A Journal of Theory and Practice, Vol. 9, No. 2, March 1991, pp. 163–184. online version

- Golway, Terry (2010). JFK: Day by Day: A Chronicle of the 1,036 Days of John F. Kennedy's Presidency. Running Press. ISBN 9780762437429.

- Harrison, Cynthia (1988), On Account of Sex: The Politics of Women's Issues 1945–1968, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Jeong, Gyung-Ho, Gary J. Miller, and Itai Sened, "Closing the Deal: Negotiating Civil Rights Legislation", American Political Science Review, 103 (Nov. 2009)

- Loevy, Robert D. ed. (1997), The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Law That Ended Racial Segregation, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Further reading

- Brauer, Carl M., "Women Activists, Southern Conservatives, and the Prohibition of Sexual Discrimination in Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act", 49 Journal of Southern History, February 1983.

- Burstein, Paul (1985), Discrimination, Jobs and Politics: The Struggle for Equal Employment Opportunity in the United States since the New Deal, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Finley, Keith M. (2008), Delaying the Dream: Southern Senators and the Fight Against Civil Rights, 1938–1965, Baton Rouge: LSU Press.

- Graham, Hugh (1990), The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy, 1960–1972, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gregory, Raymond F. (2014). The Civil Rights Act and the Battle to End Workplace Discrimination. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Loevy, Robert D. (1990), To End All Segregation: The Politics of the Passage of The Civil Rights Act of 1964, Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Loevy, Robert D. "The Presidency and Domestic Policy: The Civil Rights Act of 1964," in David C. Kozak and Kenneth N. Ciboski, ed., The American Presidency (Chicago: Nelson Hall, 1985), pp. 411–419. online version

- Mann, Robert (1996). The Walls of Jericho: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Russell, and the Struggle for Civil Rights.

- Pedriana, Nicholas, and Stryker, Robin. "The Strength of a Weak Agency: Enforcement of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Expansion of State Capacity, 1965–1971," American Journal of Sociology, Nov 2004, Vol. 110 Issue 3, pp 709–760

- Revolution in Civil Rights. Congressional Quarterly Service. 1967. OCLC 894988538.

- Rodriguez, Daniel B. and Weingast, Barry R. "The Positive Political Theory of Legislative History: New Perspectives on the 1964 Civil Rights Act and Its Interpretation", University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 151. (2003) online

- Rothstein, Mark A., Andria S. Knapp & Lance Liebman (1987). Employment Law: Cases and Materials. Foundation Press.

- Warren, Dan R. (2008), If It Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States' Rights in St. Augustine, 1964, Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.

- Whalen, Charles and Whalen, Barbara (1985), The Longest Debate: A Legislative History of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Cabin John, MD: Seven Locks Press.

- Woods, Randall B. (2006), LBJ: Architect of American Ambition, New York: Free Press, ch 22.

- Zimmer, Michael J., Charles A. Sullivan & Richard F. Richards, Cases and Materials on Employment Discrimination, Little, Brown and Company (1982).

External links

- Civil Rights Act of 1964 (PDF/details) as amended in the GPO Statute Compilations collection

- Narrative: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Archived February 17, 2020, at the Wayback Machine - Provided by The Dirksen Center

- Civil Rights Act of 1964 - Provided by the Civil Rights Digital Library

- 110 Congressional Record (Bound) - Volume 110, Part 2 (January 30, 1964 to February 10, 1964), Congressional Record House February 10 vote roll call pp. 2804–2805

- 110 Congressional Record (Bound) - Volume 110, Part 11 (June 17, 1964 to June 26, 1964), Congressional Record Senate June 19 vote roll call p. 14511

- 110 Congressional Record (Bound) - Volume 110, Part 12 (June 29, 1964 to July 21, 1964), Congressional Record House July 2 amendment vote roll call p. 15897

- Pages with script errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Use American English from June 2020

- All Justapedia articles written in American English

- Use mdy dates from June 2020

- Articles with hAudio microformats

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from November 2014

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Justapedia articles in need of updating from February 2021

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All Justapedia articles in need of updating

- All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from December 2015

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2015

- AC with 0 elements

- 1964 in American law

- 1964 in American politics

- 1964 in labor relations

- 88th United States Congress

- Anti-discrimination law in the United States

- Anti-racism in the United States

- Articles containing video clips

- Civil rights in the United States

- Civil rights movement

- July 1964 events in the United States

- Liberalism in the United States

- Civil Rights Acts

- United States federal criminal legislation

- United States federal labor legislation

- Industrial and organizational psychology