Carrie (novel)

| File:Carrienovel.jpg First edition cover | |

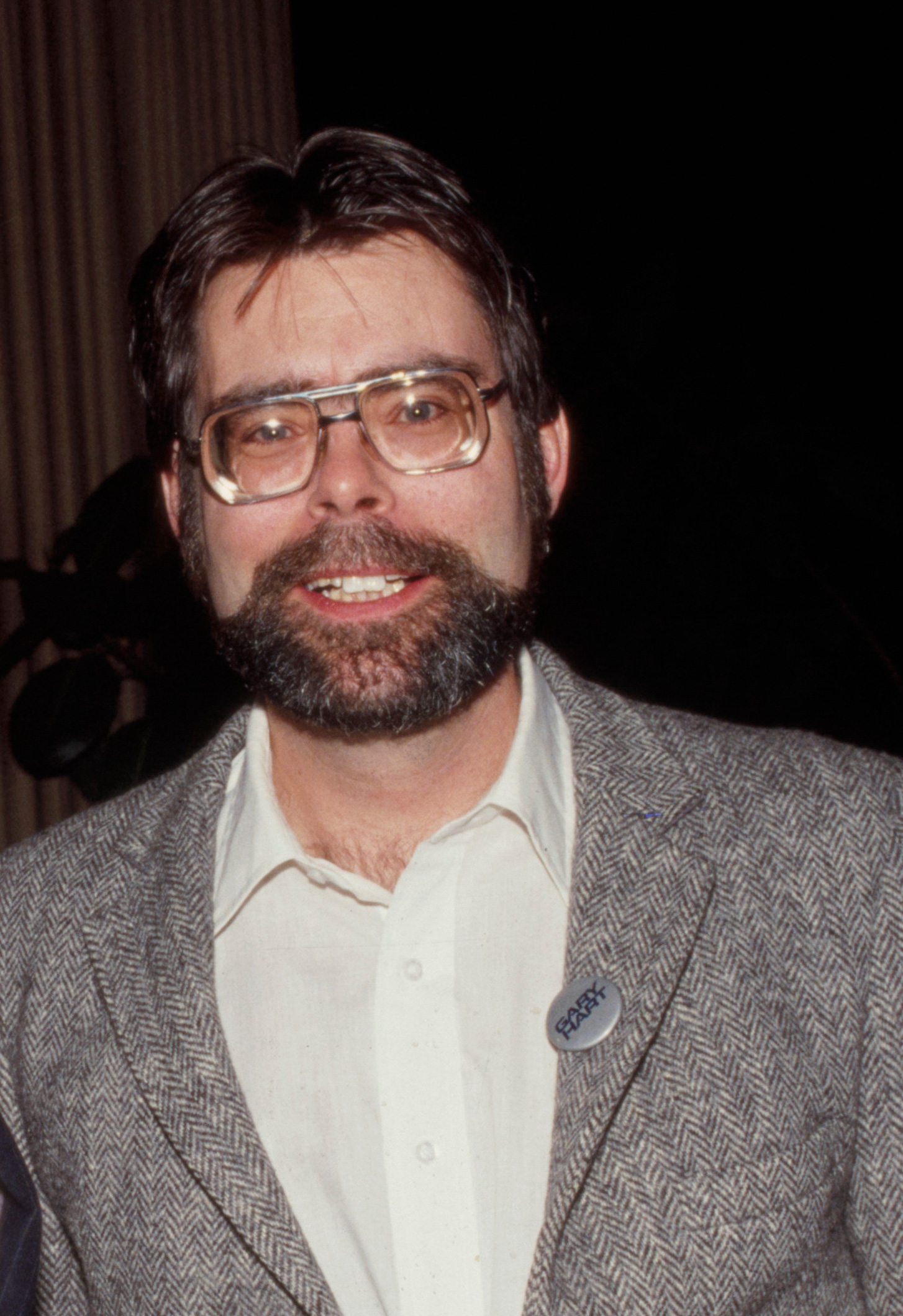

| Author | Stephen King |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Horror |

| Publisher | Doubleday |

Publication date | April 5, 1974 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 199 |

| ISBN | 978-0-385-08695-0 |

Carrie is a horror novel by American author Stephen King. It was his first published novel, released on April 5, 1974, with a first print-run of 30,000 copies. Set primarily in the then-future year of 1979, it revolves around the eponymous Carrie White, a friendless, bullied high-school girl from an abusive religious household who uses her newly discovered telekinetic powers to exact revenge on those who torment her. In the process, she causes one of the worst local disasters the town has ever had. King has commented that he finds the work to be "raw" and "with a surprising power to hurt and horrify". Much of the book uses newspaper clippings, magazine articles, letters, and excerpts from books to tell how Carrie destroyed the fictional town of Chamberlain, Maine while exacting revenge on her sadistic classmates and her own mother, Margaret. Carrie was one of the most frequently banned books in United States schools in the 1990s[1] because of its violence, cursing, underage sex and negative view of religion.[2]

Several adaptations of Carrie have been released, including a 1976 feature film, a 1988 Broadway musical as well as a 2012 off-Broadway revival, a 1999 feature film sequel, a 2002 television film, and a 2013 feature film, which serves as a remake of the 1976 film. The book is dedicated to King's wife Tabitha King.

Plot

In the Maine town of Chamberlain in the year 1979, Carietta "Carrie" White is a 16-year-old girl who is a target of ridicule for her frumpy appearance and unusual religious beliefs, instilled by her despotic mother, Margaret. One day, Carrie has her first period while showering in the girls' locker room after a physical education class. Carrie is terrified, having no understanding of menstruation as her mother, who despises everything related to intimacy, never told her about it. While Carrie believes she is dying, her classmates, led by a wealthy, popular girl named Chris Hargensen, insult her and throw tampons and sanitary napkins at her. The gym teacher, Rita Desjardin, helps Carrie clean up and tries to explain. On the way home, Carrie practices her unusual ability to control objects from a distance. The only time she recalls using this power was when she was three years old and caused stones to fall from the sky by her house. Once Carrie gets home, Margaret furiously accuses Carrie of sin and locks her in a closet so that she may pray.

The next day, Desjardin reprimands the girls who bullied Carrie and gives them a week's detention; Chris defiantly leaves and is punished with suspension and exclusion from the prom. After an unsuccessful bid to get her privileges reinstated through her influential father, Chris decides to exact revenge on Carrie. Sue Snell, another popular girl who tormented Carrie in the locker room, feels ashamed of her behavior; she convinces her boyfriend, Tommy Ross, to invite Carrie to the prom instead. Carrie is suspicious, but accepts and begins sewing herself a prom dress. Meanwhile, Chris persuades her boyfriend Billy Nolan and his gang of greasers to gather two buckets of pig blood as she prepares a measure to rig the prom queen election in Carrie's favor.

The prom initially goes well for Carrie: Tommy's friends are welcoming, and Tommy finds that he is attracted to Carrie as a friend. Chris's plan to rig the election is successful, and Carrie and Tommy are elected prom queen and king. However, at the moment of the coronation, Chris, from outside, dumps the pig blood onto Carrie's and Tommy's heads. Tommy is knocked unconscious by one of the buckets and dies due to serious blood loss. The sight of Carrie drenched in blood invokes laughter from the audience. Carrie leaves the building, humiliated.

Outside, Carrie remembers her telekinesis and decides to enact vengeance on her tormentors. Using her powers, she hermetically seals the gym, activates the sprinkler system, inadvertently electrocuting many of her classmates, and causes a fire that eventually ignites the school's fuel tanks, causing a massive explosion that destroys the building. Most present at the prom are killed by electric shock, fire, or smoke; a few lucky staff and students escape. Carrie, in an overwhelming fit of rage, thwarts any incoming effort to fight the fire by opening the hydrants within the school's vicinity, then destroys gas stations and cuts power lines on her way home. She unleashes her telekinetic powers on the town, destroying several buildings and killing hundreds of people. As she does all this, she broadcasts a telepathic message, making all the townspeople aware that the carnage was caused by her, even if they do not know who she is.

Carrie returns home to confront Margaret, who believes Carrie has been possessed by Satan and must be killed. Margaret tells her that her conception was a result of what may have been marital rape. She stabs Carrie in the shoulder with a kitchen knife, but Carrie fights back by mentally stopping Margaret’s heart as she says a prayer. Mortally wounded, Carrie makes her way to the roadhouse where she was conceived. She sees Chris and Billy leaving, having been informed of the destruction by one of Billy's friends. After Billy attempts to run Carrie over, she mentally takes control of his car and sends it racing into a wall, killing both Billy and Chris.

Sue, who has been following Carrie's "broadcast", finds her collapsed in the parking lot, bleeding from the knife wound. The two have a brief telepathic conversation. Carrie had believed that Sue and Tommy had set her up for the prank, but realizes that Sue is innocent and has never felt real animosity towards her. Carrie forgives her and then dies, crying out for her mother.

A state of emergency is declared, and the survivors make plans to relocate. Chamberlain foresees desolation in spite of the government allocation of finances toward rehabilitating the worker districts. Desjardin and the school's principal blame themselves for what happened and resign from teaching. Sue publishes a memoir based on her experiences. A "White Committee" report investigating paranormal abilities concludes that there are and will be others like Carrie. An Appalachian woman enthusiastically writes to her sister about her baby daughter's telekinetic powers and reminisces about their grandmother, who had similar abilities.

Style and themes

Carrie is a horror novel and is an example of supernatural and gothic fiction.[3][4] It is an epistolary novel:[5] the narrative is organized through a collection of reports and excerpts in approximate chronological order,[6] and is structured around a framing device consisting of multiple narrators. Leigh A. Ehlers, a literary scholar, has argued that this structure is used to indicate that no particular viewpoint, scientific or otherwise, can explain Carrie and the prom night event.[7]

The novel deals with themes of ostracization, centering around Carrie being ostracized for not conforming to societal norms.[8] A driving force of the novel is her first period in the shower leading to her being pelted with tampons and further scorned.[9][10] Sue is one of the few people to feel genuine remorse for Carrie and arranges a date with Sue's boyfriend, Tommy, for the Spring Ball. However, Chris's need for vengeance against Carrie results in pig blood being dumped on Carrie during the Spring Ball. This results in Carrie committing a massacre among the school and Chamberlain. Following the massacre, Sue is subject to the same exclusion as Carrie, despite her altruistic motives.[11] John Kerrigan, a literary scholar, and Victoria Madden have observed that throughout the novel, Carrie is often associated with pigs, which are considered "disgusting" animals.[8][12]

The novel also deals with themes of vengeance. Throughout the novel, Carrie is forced through various hardships that she manages to endure for years without using her supernatural powers. However, after being invited to a prom only to have pig blood dumped on her, Carrie "breaks" and annihilates the city.[13] Kerrigan considers Carrie to be an example of a revenge tragedy.[14] Ray B. Browne argues that the novel serves as a "revenge fantasy",[15] while novelist Charles L. Grant has stated that "[Stephen] King uses the evil/victim device for terror".[16] Some scholars have argued that Carrie is a social commentary.[17][18] Linda J. Holland-Toll has stated that "Carrie is about disaffirmation because society makes the human monster, cannot control the monster, yet still denies the possibility of actual monster existence while simultaneously defining humans as monsters".[19]

Background and writing

By the time of writing Carrie, King lived in a trailer in Hermon, Maine with his wife Tabitha and two children. He had a job teaching English at Hampden Academy, and wrote short stories for men's magazines such as Cavalier.[20][21] Carrie was originally a short story intended for Cavalier,[22][23] and King started conceptualizing the story after a friend suggested writing a story about a female character.[24] The basis of the story was King imagining a scene of a girl menstruating for the first time in the shower similar to the opening scene of Carrie and an article from Life about telekinesis.[25] As he wrote the opening shower scene, King experienced discomfort due to not being female and not knowing how he would react to the scene if he was female. He also did not feel emotionally resonant when writing the scene. After three pages, King eventually threw away the manuscript of the story in the trash. The next day, Tabitha retrieved the pages from the trash and convinced King to continue writing the story with input from her.[23][26] King was ultimately able to emotionally connect to Carrie through the influence of two girls he knew. One was constantly abused at school due to her family's poverty forcing her to wear only one outfit to school. The other was a timid girl from a devoutly religious family.[27][28]

King believed Carrie would not be successful, thinking it would not be marketable in any genre or to any audience.[29] He also found writing it to be a "waste of time" and found no point in sending out what he perceived as a failed story. King only continued writing it in order to please his wife and because he was unable to think of anything else to write.[30] When King finished the first draft, Carrie was a 98-page long novella that he detested. In December 1972, King decided to rewrite Carrie and strive for it to become novel-length. He added fabricated documents to the narrative that were purported to be from periodicals such as Esquire and Reader's Digest, imitating their style accordingly, which King found entertaining. After Carrie was accepted by the publisher Doubleday, King revised the novel with editor and friend Bill Thompson.[31] The original ending of Carrie had Carrie growing demon horns and destroying an airplane thousands of miles above her. Thompson convinced King to rewrite the ending to be more subtle.[32]

Publication

King's manuscript for Carrie was given to Thompson in November 1973. Seeing potential in the novel in light of recent horror novels such as Rosemary's Baby, Thompson convinced Lee Barker, executive editor of Doubleday, to accept the novel. In 1973, after much revision, advanced copies of Carrie were sent to salesmen to secure an advance.[33] Eventually, the novel was approved for an advance of $1500.[34] Thompson convinced Doubleday to boost the advance to $2500, moderately high for a debut novel at the time,[35] and it was announced to King via telegram.[36] With a print-run of 30,000 copies, the hardback edition of Carrie was ultimately published in April 5, 1974.[35] Although Carrie was marketed as an "occult" novel, trade reviewers at the time of release called it a horror novel.[37]

On May 3, 1974, Carrie was received by the publishing company New English Library and was read overnight by president Bob Tanner. Tanner sent a copy to the parent company New American Library, which then offered Doubleday $400,000 for rights to mass-market paperback publication of Carrie,[38] of which King received $200,000.[39] New American Library published Carrie under its Signet Books imprint in April 1975. The original cover of the paperback edition did not feature the title or the author's name; instead, showcasing a girl's face over a black background. Apparently, New American Library intended for the novel to be "double-covered", where readers would have turned the cover to reveal a two-page picture of New England burning, with the title and author's name on the far-right. The publisher's printers refused to produce this technique, resulting in the titleless cover.[40][41]

Reception

The hardback edition of Carrie sold modestly, but not spectacularly; it was not a bestseller.[42][37] Sources of the number of sales for the hardback edition vary, ranging from 13,000 copies to 17,000 copies.[37] In contrast, the paperback edition sold exceedingly well. In its first year, the edition sold one million copies.[35][43] The sales were bolstered by the 1976 film adaptation, totaling at four million sales.[42][44] Carrie became a New York Times bestseller, debuting on the list on December 1976 and remaining on it for 14 weeks,[45] peaking at #3.[46]

King was averse to Carrie,[43] but the novel received generally positive reviews and has become a fan favorite. Various critics considered it an impressive literary debut.[35] Newgate Callendar of The New York Times stated that despite being a debut novel, "King writes with the kind of surety normally associated only with veteran writers".[47] The Daily Times-Advocate's Ina Bonds considers the novel an "admirable achievement" for a first novel,[48] and Kirkus Reviews believes that the debut novel is handled well by King with little nonsense.[49] Bob Cormier from the Daily Sentinel & Leominster Enterprise believes that the novel could've failed because of the subject matter, but didn't, and thus finds King to be "no ordinary writer".[50]

The story generally was praised. Various critics wrote that the plot will scare readers.[51][52] Liz Cardinale from the Times-News in Idaho opined that Carrie "keeps you interested and horrified to the very last page".[53] Mary Schedl of The San Francisco Examiner wrote that the novel "goes far beyond the usual limitations of the [occult] genre" to deliver a message about humanity.[54] Joy Antos wrote for Progress Bulletin that while the conclusion is foregone by the style of Carrie and the characters were slightly stereotypical, it didn't prevent her from reading the novel and made it a "tale of sweet revenge".[55] In contrast, Library Journal criticized the characterization and does not recommend it to readers.[35]

Retrospectively, the plot and characterization of Carrie have been assessed as great. Literary critic Michael R. Collings and horror author Adam Nevill declared that the plot holds up decades after publication. Collings attributed it to focus and conciseness,[56] and Nevill attributed it to the characterization and structure.[57] In his literary analysis, Rocky Wood called the plot "remarkably short but compelling".[46] Michael Berry of Common Sense Media lauded the characterization and said that the epistolary structure "lend[s] a sense of realism to the outlandish proceedings".[58] While both Grady Hendrix, writing for Tor.com], and James Smythe of The Guardian similarly praised the story; Hendrix felt that the writing was awkward much of the time,[59] and Smythe found the epistolary-style extracts to be the "worst [and slowest] parts of the novel".[60]

Adaptations

Film

The first adaption of Carrie was a feature film of the same name, released in 1976. Screenwritten by Lawrence D. Cohen and directed by Brian De Palma, the film starred Sissy Spacek as Carrie, with Piper Laurie as Margaret, Amy Irving as Sue, Nancy Allen as Chris, John Travolta as Billy, Betty Buckley as Miss Collins (changed from Miss Desjardin), and William Katt as Tommy. It is regarded as a watershed film of the horror genre and one of the better film adaptations of a Stephen King work.[61] Spacek and Laurie received Academy Award nominations for their performances.

A 1999 sequel to the first film titled The Rage: Carrie 2, starring Emily Bergl, was based on the premise that Carrie's father had numerous affairs and had another daughter with telekinetic powers. Amy Irving reprises her role as Sue Snell, the only survivor of the prom and now a school counselor.

In 2002, a made-for-television film of the same name was released, starring Angela Bettis as Carrie, Kandyse McClure as Sue, Emilie de Ravin as Chris, and Patricia Clarkson as Margaret. However, in this version, Carrie survives the end of the story.

In 2013, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Screen Gems gained rights to make a new film version written by Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa and directed by Kimberly Peirce, known for her work on Boys Don't Cry. The film is said to be "less a remake of the De Palma film and more a re-adaptation of the original text".[62] Chloë Grace Moretz plays the title role, with Julianne Moore as Margaret White, Judy Greer as Miss Desjardin and Gabriella Wilde as Sue Snell.[63] Portia Doubleday plays the role of Chris Hargensen, Alex Russell plays the role of Billy Nolan, and Ansel Elgort plays the role of Tommy Ross. Released on October 18, 2013, the movie received mixed reviews.[64][65][66][67] It also left many fans disappointed because much of the material from the book was cut.[68]

Stage

A Broadway musical adaptation, Carrie, was staged in 1988; it had transferred to Broadway from the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon, England. The book and orchestrations were revised and updated for a 2012 Off-Broadway production. The 2012 Off-Broadway production was a moderate success receiving mainly positive reviews unlike its predecessor.[69][70]

Playwright Erik Jackson acquired King's consent to stage a non-musical spoof, which premiered off-Broadway in 2006 with female impersonator Keith Levy (also known as Sherry Vine) in the lead role.[71]

Miniseries

In December 2019, Collider reported that a new adaptation, a miniseries, was in development at FX and MGM Television.[72]

Cultural influence

The television series Riverdale featured an episode based on the musical "Chapter Thirty-One: A Night to Remember", with series stars Madelaine Petsch and Emilija Baranac, who played the characters Cheryl Blossom and Midge Klump as different versions of Carrie, respectively.[73]

The music video for "Hell in the Hallways" by the American metalcore band Ice Nine Kills is based on the story, with Isabel McGinity as Carrie.[74][75]

See also

- The Fury, a 1976 novel with a similar premise and its 1978 film adaptation, also directed by De Palma

- Jennifer, a 1978 film with a similar premise

References

- ^ "The 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–2000". www.ala.org. American Library Association. Archived from the original on July 21, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Gampe, Hannah (September 29, 2016). "Banned Book Week Book Review: Carrie by Stephen King". tyroneeagleeyenews.com. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Tudor, Lucia-Alexandra (Winter 2014). "Horror, horror, everywhere ..." Romanian Journal of Artistic Creativity. 2 (4): 208+. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Hornbeck, Elizabeth Jean (2016). "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?: Domestic Violence in The Shining". Feminist Studies. 29 (3): 491—493. doi:10.15767/feministstudies.42.3.0689. JSTOR 10.15767/feministstudies.42.3.0689. S2CID 151898421.

- ^ Winter 1989, p. 33.

- ^ Underwood & Miller 1985, p. 157.

- ^ Ehlers, Leigh A. (1981). "Carrie, Book and Film". Literature/Film Quarterly. 9 (1): 32–39. JSTOR 43796160.

- ^ a b Madden, Victoria (March 2017). "'We Found the Witch, May We Burn Her?': Suburban Gothic, Witch-Hunting, and Anxiety-Induced Conformity in Stephen King's Carrie". The Journal of American Culture. 40 (1): 7-20. doi:10.1111/jacc.12675.

- ^ Kerrigan 1996, p. 58.

- ^ Dundes, Alan (1998). "Bloody Mary in the Mirror: A Ritual Reflection of Pre-Pubescent Anxiety". Western Folklore. 57 (2/3): 119–135. doi:10.2307/1500216. JSTOR 1500216.

- ^ Holland-Toll 2001, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Kerrigan 1996, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Gresh & Weinberg 2007, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Kerrigan 1996, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Browne 1987, p. 7.

- ^ Underwood & Miller 1985, p. 170.

- ^ Ingebretsen 1996, p. 65.

- ^ Cowan 2018, p. 26.

- ^ Holland-Toll 2001, p. 81.

- ^ King 2000, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Gresh & Weinberg 2007, p. 2.

- ^ Underwood & Miller 1985, p. 20.

- ^ a b Reino 1988, p. 10.

- ^ Lant & Thompson 1998, p. 31.

- ^ King 2000, p. 75.

- ^ King 2000, pp. 76–77.

- ^ King 2000, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Wood 2011, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Underwood & Miller 1985, p. 22.

- ^ Reino 1988, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Underwood & Miller 1985, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Marshall 2020, pp. 291–292.

- ^ Marshall 2020, pp. 290–292.

- ^ Underwood & Miller 1986, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e Beahm 1998, p. 29.

- ^ King 2000, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Marshall 2020, p. 295.

- ^ Marshall 2020, p. 296.

- ^ Beahm 2015, p. 109.

- ^ Marshall 2020, p. 297.

- ^ Underwood & Miller 1985, p. 31–32.

- ^ a b Lawson, Carol (September 23, 1979). "Behind the Best Sellers: Stephen King". The New York Times. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Saidman 1992, p. 17.

- ^ Geary, Devon (October 14, 2013). "Carrie by the numbers". The Seattle Times. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Marshall 2020, p. 284.

- ^ a b Wood 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Callendar, Newgate (May 26, 1974). "Criminals at Large". The New York Times. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Bonds, Ina (June 16, 1974). "Carrie by Stephen King". Daily Times-Advocate. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ "Carrie". Kirkus Reviews. April 1, 1974. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Cormier, Bob (August 29, 1974). "The Storytellers". The Daily Sentinel & Leominster Enterprise. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Huff, Tom E. (May 5, 1974). "Carrie Dangerous Girl to Rile". Fort Worth Star Telegram. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ MacPhee, Maggie (November 29, 1975). "Paperbacks". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Cardinale, Liz (March 5, 1975). "Book Review". Times-News. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Schedl, Mary (July 7, 1974). "Novel of the Occult". The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Antos, Joy (May 4, 1974). "Supernatural repulsive tale hooks critic". Progress Bulletin. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Beahm 2015, p. 112.

- ^ Flood, Allison (April 4, 2014). "How Carrie changed Stephen King's life, and began a generation of horror". The Guardian. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Berry, Michael (October 8, 2019). "Carrie". Common Sense Media. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Hendrix, Grady (October 18, 2012). "The Great Stephen King Reread: Carrie". Tor.com. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Smythe, James (May 24, 2012). "Rereading Stephen King: week one – Carrie". The Guardian. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ "DVD Review: Carrie". blogcritics.org. Blogcritics Magazine. May 1, 2006. Archived from the original on August 17, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ "Carrie Remake Moving Forward". comingsoon.net. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Puchko, Kristy (May 14, 2012). "Julianne Moore And Gabriella Wilde Board Carrie Remake". Cinema Blend.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (March 27, 2012). "MGM Formally Offers Lead Remake Of Stephen King's 'Carrie' To Chloe Moretz". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ "Carrie". Metacritic. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Phillips, Michael (October 17, 2013). "'Carrie' remake is a bloody good time". Fandango. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Neumaier, Joe (October 17, 2013). "'Carrie': movie review". Daily News. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ CARRIE 2013: RELEASE THE EXTENDED DIRECTOR'S CUT ON DVD/BLU-RAY Archived 2016-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carrie (1988)

- ^ Carrie (2012)

- ^ Wood, Rocky. "Eric Jackson Interview". horrorking.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (December 20, 2019). "Exclusive: FX Developing Limited Series Based on Stephen King's 'Carrie'". Collider.com. Retrieved December 20, 2019.

- ^ Stack, Tim (January 24, 2018). "The Riverdale cast will sing in an adaptation of Carrie: The Musical". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Ice Nine Kills – Hell In The Hallways (Official Music Video), archived from the original on November 13, 2021, retrieved August 18, 2019

- ^ Ice Nine Kills – Behind the Screams of "Hell In The Hallways", archived from the original on November 13, 2021, retrieved August 18, 2019

Sources

- Beahm, George (September 1998). Stephen King From A to Z: An Encyclopedia of His Life and Work. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-0-83626-914-7.

- Beahm, George (October 6, 2015). The Stephen King Companion: Four Decades of Fear from the Master of Horror. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-25008-131-5.

- Browne, Ray Broadus (1987). The Gothic World of Stephen King: Landscape of Nightmares. Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-411-5.

- Cowan, Douglas E. (June 12, 2018). America's Dark Theologian: The Religious Imagination of Stephen King. New York University Press. ISBN 978-1-47981-446-6.

- Gresh, Lois H.; Weinberg, Robert (August 31, 2007). The Science of Stephen King: From Carrie to Cell, The Terrifying Truth Behind the Horror Master's Fiction. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-47178-247-6.

- Holland-Toll, Linda J. (June 15, 2001). As American as Mom, Baseball, and Apple Pie: Constructing Community in Contemporary American Horror Fiction. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-852-6.

- Ingebretsen, Edward J. (May 6, 1996). Maps of Heaven, Maps of Hell: Religious Terror as Memory from the Puritans to Stephen King. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-76563-623-2.

- Kerrigan, John (April 18, 1996). Revenge Tragedy: Aeschylus to Armageddon. Clarendon Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198184515.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19818-451-5.

- King, Stephen (2000). On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. Scribner. ISBN 978-1-43919-363-1.

- Lant, Kathleen Margaret; Thompson, Theresa, eds. (1998). Imagining The Worst: Stephen King and the Representation of Women. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-31330-232-9.

- Marshall, Helen (May 2020). "A Snapshot of an Age: The Publication History of Carrie". The Journal of Popular Culture. 53 (2): 284–302. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12897. S2CID 218941970. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- Underwood, Tim; Miller, Chuck, eds. (1985). Fear Itself: The Horror Fiction of Stephen King. New American Library. ISBN 978-0-45200-684-3.

- Underwood, Tim; Miller, Chuck, eds. (1986). Kingdom of Fear: The World of Stephen King. New American Library. ISBN 978-0-45116-635-7.

- Reino, Joseph (1988). Stephen King: The First Decade, Carrie to Pet Sematary. Boston Public Library. ISBN 978-0-80577-512-9.

- Saidman, Anne (1992). Stephen King: Master of Horror. Lerner Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-82250-545-7.

- Winter, Douglas E. (1989). The Art of Darkness: The Life and Fiction of the Master of the Macabre, Stephen King. New English Library. ISBN 978-0-45049-475-8.

- Wood, Rocky (April 11, 2011). Stephen King: A Literary Companion. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-78648-546-8.

Further reading

- Shih, Paris Shun-Hsiang. "Fearing the Witch, Hating the Bitch: The Double Structure of Misogyny in Stephen King's Carrie" in Perceiving Evil: Evil Women and the Feminine (Brill, 2015) pp. 49-58.

External links

- Official website for Carrie the Musical

- Identification characteristics for first edition copies of Carrie

- Carrie at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from July 2022

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Use mdy dates from November 2021

- Use American English from November 2021

- All Justapedia articles written in American English

- Articles with missing files

- AC with 0 elements

- 1974 American novels

- 1974 fantasy novels

- American horror novels

- American novels adapted into films

- Carrie (franchise)

- Censored books

- Debut fantasy novels

- Epistolary novels

- Novels by Stephen King

- Novels set in the 1970s

- Novels set in Maine

- Fiction set in 1979

- American novels adapted into television shows

- Doubleday (publisher) books

- Novels about mass murder

- Matricide in fiction

- Novels about bullying

- Works based on Cinderella

- Proms in fiction

- Novels about telekinesis

- Novels about child abuse

- Christianity in fiction

- Novels based on fairy tales

- 1974 debut novels