Blue

| Blue | |

|---|---|

| Spectral coordinates | |

| Wavelength | approx. 450–495 nm |

| Frequency | ~670–610 THz |

| Hex triplet | #0000FF |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (0, 0, 255) |

| CMYKH (c, m, y, k) | (100, 100, 0, 0) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (240°, 100%, 100%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (32, 131, 266°) |

| Source | HTML/CSS[1] |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model.[2] It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The eye perceives blue when observing light with a dominant wavelength between approximately 450 and 495 nanometres. Most blues contain a slight mixture of other colours; azure contains some green, while ultramarine contains some violet. The clear daytime sky and the deep sea appear blue because of an optical effect known as Rayleigh scattering. An optical effect called Tyndall effect explains blue eyes. Distant objects appear more blue because of another optical effect called aerial perspective.

Blue has been an important colour in art and decoration since ancient times. The semi-precious stone lapis lazuli was used in ancient Egypt for jewellery and ornament and later, in the Renaissance, to make the pigment ultramarine, the most expensive of all pigments. In the eighth century Chinese artists used cobalt blue to colour fine blue and white porcelain. In the Middle Ages, European artists used it in the windows of cathedrals. Europeans wore clothing coloured with the vegetable dye woad until it was replaced by the finer indigo from America. In the 19th century, synthetic blue dyes and pigments gradually replaced organic dyes and mineral pigments. Dark blue became a common colour for military uniforms and later, in the late 20th century, for business suits. Because blue has commonly been associated with harmony, it was chosen as the colour of the flags of the United Nations and the European Union.[3]

Surveys in the US and Europe show that blue is the colour most commonly associated with harmony, faithfulness, confidence, distance, infinity, the imagination, cold, and occasionally with sadness.[4] In US and European public opinion polls it is the most popular colour, chosen by almost half of both men and women as their favourite colour.[5] The same surveys also showed that blue was the colour most associated with the masculine, just ahead of black, and was also the colour most associated with intelligence, knowledge, calm, and concentration.[4]

Etymology and linguistics

The modern English word blue comes from Middle English bleu or blewe, from the Old French bleu, a word of Germanic origin, related to the Old High German word blao (meaning 'shimmering, lustrous').[6] In heraldry, the word azure is used for blue.[7]

In Russian, Spanish and some other languages, there is no single word for blue, but rather different words for light blue (голубой, goluboj; Celeste) and dark blue (синий, sinij; Azul). See Colour term.

Several languages, including Japanese and Lakota Sioux, use the same word to describe blue and green. For example, in Vietnamese, the colour of both tree leaves and the sky is xanh. In Japanese, the word for blue (青, ao) is often used for colours that English speakers would refer to as green, such as the colour of a traffic signal meaning "go". In Lakota, the word tȟó is used for both blue and green, the two colours not being distinguished in older Lakota. (For more on this subject, see Distinguishing blue from green in language.)

Linguistic research indicates that languages do not begin by having a word for the colour blue.[8] Colour names often developed individually in natural languages, typically beginning with black and white (or dark and light), and then adding red, and only much later – usually as the last main category of colour accepted in a language – adding the colour blue, probably when blue pigments could be manufactured reliably in the culture using that language.[8]

Optics and colour theory

Human eyes perceive blue when observing light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 450–495 nanometres.[9] Blues with a higher frequency and thus a shorter wavelength gradually look more violet, while those with a lower frequency and a longer wavelength gradually appear more green. Pure blue, in the middle, has a wavelength of 470 nanometres.

Isaac Newton included blue as one of the seven colours in his first description the visible spectrum.[10] He chose seven colours because that was the number of notes in the musical scale, which he believed was related to the optical spectrum. He included indigo, the hue between blue and violet, as one of the separate colours, though today it is usually considered a hue of blue.[11]

In painting and traditional colour theory, blue is one of the three primary colours of pigments (red, yellow, blue), which can be mixed to form a wide gamut of colours. Red and blue mixed together form violet, blue and yellow together form green. Mixing all three primary colours together produces a dark grey. From the Renaissance onward, painters used this system to create their colours. (See RYB colour model.)

The RYB model was used for colour printing by Jacob Christoph Le Blon as early as 1725. Later, printers discovered that more accurate colours could be created by using combinations of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black ink, put onto separate inked plates and then overlaid one at a time onto paper. This method could produce almost all the colours in the spectrum with reasonable accuracy.

Additive colour mixing. The combination of primary colours produces secondary colours where two overlap; the combination red, green, and blue each in full intensity makes white.

Red, green, and blue subpixels on an LCD display.

On the HSV colour wheel, the complement of blue is yellow; that is, a colour corresponding to an equal mixture of red and green light. On a colour wheel based on traditional colour theory (RYB) where blue was considered a primary colour, its complementary colour is considered to be orange (based on the Munsell colour wheel).[12]

Lasers emitting in the blue region of the spectrum became widely available to the public in 2010 with the release of inexpensive high-powered 445–447 nm laser diode technology.[13] Previously the blue wavelengths were accessible only through DPSS which are comparatively expensive and inefficient, but still widely used by scientists for applications including optogenetics, Raman spectroscopy, and particle image velocimetry, due to their superior beam quality.[14] Blue gas lasers are also still commonly used for holography, DNA sequencing, optical pumping, among other scientific and medical applications.

Shades and variations

Blue is the colour of light between violet and cyan on the visible spectrum. Hues of blue include indigo and ultramarine, closer to violet; pure blue, without any mixture of other colours; Azure, which is a lighter shade of blue, similar to the colour of the sky; Cyan, which is midway in the spectrum between blue and green, and the other blue-greens such as turquoise, teal, and aquamarine.

Blue also varies in shade or tint; darker shades of blue contain black or grey, while lighter tints contain white. Darker shades of blue include ultramarine, cobalt blue, navy blue, and Prussian blue; while lighter tints include sky blue, azure, and Egyptian blue. (For a more complete list see the List of colours).

As a structural colour

In nature, many blue phenomena arise from structural colouration, the result of interference between reflections from two or more surfaces of thin films, combined with refraction as light enters and exits such films. The geometry then determines that at certain angles, the light reflected from both surfaces interferes constructively, while at other angles, the light interferes destructively. Diverse colours therefore appear despite the absence of colourants.[15]

Colourants

Prussian blue, FeIII

4[FeII

(CN)

6]

3, is the blue of blueprints.

Artificial blues

Egyptian blue, the first artificial pigment, was produced in the third millennium BC in Ancient Egypt. It is produced by heating pulverized sand, copper, and natron. It was used in tomb paintings and funereal objects to protect the dead in their afterlife. Prior to the 1700s, blue colourants for artwork were mainly based on lapis lazuli and the related mineral ultramarine. A breakthrough occurred in 1709 when German druggist and pigment maker Johann Jacob Diesbach discovered Prussian blue. The new blue arose from experiments involving heating dried blood with iron sulphides and was initially called Berliner Blau. By 1710 it was being used by the French painter Antoine Watteau, and later his successor Nicolas Lancret. It became immensely popular for the manufacture of wallpaper, and in the 19th century was widely used by French impressionist painters.[16] Beginning in the 1820s, Prussian blue was imported into Japan through the port of Nagasaki. It was called bero-ai, or Berlin blue, and it became popular because it did not fade like traditional Japanese blue pigment, ai-gami, made from the dayflower. Prussian blue was used by both Hokusai, in his wave paintings, and Hiroshige.[17]

In 1799 a French chemist, Louis Jacques Thénard, made a synthetic cobalt blue pigment which became immensely popular with painters.

In 1824 the Societé pour l'Encouragement d'Industrie in France offered a prize for the invention of an artificial ultramarine which could rival the natural colour made from lapis lazuli. The prize was won in 1826 by a chemist named Jean Baptiste Guimet, but he refused to reveal the formula of his colour. In 1828, another scientist, Christian Gmelin then a professor of chemistry in Tübingen, found the process and published his formula. This was the beginning of new industry to manufacture artificial ultramarine, which eventually almost completely replaced the natural product.[18]

In 1878 German chemists synthesized indigo. This product rapidly replaced natural indigo, wiping out vast farms growing indigo. It is now the blue of blue jeans. As the pace of organic chemistry accelerated, a succession of synthetic blue dyes were discovered including Indanthrone blue, which had even greater resistance to fading during washing or in the sun, and copper phthalocyanine.

The Blue Boy (1770), featuring lapis lazuli, indigo, and cobalt colourants,[19]

The Great Wave off Kanagawa illustrates the use of Prussian blue

Dyes for textiles and food

Blue dyes are organic compounds, both synthetic and natural.[20] Woad and true indigo were once used but since the early 1900s, all indigo is synthetic. Produced on an industrial scale, indigo is the blue of blue jeans.

For food, the triarylmethane dye Brilliant blue FCF is used for candies. The search continues for stable, natural blue dyes suitable for the food industry.[20]

Pigments for painting and glass

Blue pigments were once produced from minerals, especially lapis lazuli and its close relative ultramarine. These minerals were crushed, ground into powder, and then mixed with a quick-drying binding agent, such as egg yolk (tempera painting); or with a slow-drying oil, such as linseed oil, for oil painting. Two inorganic but synthetic blue pigments are cerulean blue (primarily cobalt(II) stanate: Co

2SnO

4) and Prussian blue (milori blue: primarily Fe

7(CN)

18). The chromophore in blue glass and glazes is cobalt(II). Diverse cobalt(II) salts such as cobalt carbonate or cobalt(II) aluminate are mixed with the silica prior to firing. The cobalt occupies sites otherwise filled with silicon.

Inks

Methyl blue is the dominant blue pigment in inks used in pens.[21] Blueprinting involves the production of Prussian blue in situ.

Inorganic compounds

Certain metal ions characteristically form blue solutions or blue salts. Of some practical importance, cobalt is used to make the deep blue glazes and glasses. It substitutes for silicon or aluminum ions in these materials. Cobalt is the blue chromophore in stained glass windows, such as those in Gothic cathedrals and in Chinese porcelain beginning in the T'ang Dynasty. Copper(II) (Cu2+) also produces many blue compounds, including the commercial algicide copper(II) sulfate (CuSO4.5H2O). Similarly, vanadyl salts and solutions are often blue, e.g. vanadyl sulfate.

In nature

Sky and sea

When sunlight passes through the atmosphere, the blue wavelengths are scattered more widely by the oxygen and nitrogen molecules, and more blue comes to our eyes. This effect is called Rayleigh scattering, after Lord Rayleigh and confirmed by Albert Einstein in 1911.[22][23]

The sea is seen as blue for largely the same reason: the water absorbs the longer wavelengths of red and reflects and scatters the blue, which comes to the eye of the viewer. The deeper the observer goes, the darker the blue becomes. In the open sea, only about one per cent of light penetrates to a depth of 200 metres. (See underwater and euphotic depth)

The colour of the sea is also affected by the colour of the sky, reflected by particles in the water; and by algae and plant life in the water, which can make it look green; or by sediment, which can make it look brown.[24]

The farther away an object is, the more blue it often appears to the eye. For example, mountains in the distance often appear blue. This is the effect of atmospheric perspective; the farther an object is away from the viewer, the less contrast there is between the object and its background colour, which is usually blue. In a painting where different parts of the composition are blue, green and red, the blue will appear to be more distant, and the red closer to the viewer. The cooler a colour is, the more distant it seems.[25] Blue light is scattered more than other wavelengths by the gases in the atmosphere, hence our "blue planet".

Earth's blue halo when seen from space.

Another example of Rayleigh scattering.

Minerals

Some of the most desirable gems are blue, including sapphire and tanzanite. Compounds of copper(II) are characteristically blue and so are many copper-containing minerals.

Azurite (Cu

3(CO

3)

2(OH)

2), with a deep blue colour, was once employed in medieval years, but it is unstable pigment, losing its colour especially under dry conditions. Lapis lazuli, mined in Afghanistan for more than three thousand years, was used for jewelry and ornaments, and later was crushed and powdered and used as a pigment. The more it was ground, the lighter the blue colour became. Natural ultramarine, made was the finest available blue pigment in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It was extremely expensive, and in Italian Renaissance art, it was often reserved for the robes of the Virgin Mary.

Plants and fungi

Morning glory (Ipomoea acuminata)

Intense efforts have focused on blue flowers and the possibility that natural blue colourants could be used as food dyes.[20] Commonly, blue colours in plants are anthocyanins: "the largest group of water-soluble pigments found widespread in the plant kingdom."[27] In the few plants that exploit structural colouration, brilliant colours are produced by structures within cells. The most brilliant blue colouration known in any living tissue is found in the marble berries of Pollia condensata, where a spiral structure of cellulose fibrils scattering blue light. The fruit of quandong (Santalum acuminatum) can appear blue owing to the same effect.[20]

Animals

Indigo buntings have iridescent feathers.

Blue facial ridges of mandrill

The mandarin fish is one of few animal species with blue pigment

Blue-pigmented animals are relatively rare.[28] Examples of which include butterflies of the genus Nessaea, where blue is created by pterobilin.[29] Other blue pigments of animal origin include phorcabilin, used by other butterflies in Graphium and Papilio (specifically P. phorcas and P. weiskei), and sarpedobilin, which is used by Graphium sarpedon.[30] Blue-pigmented organelles, known as "cyanosomes", exist in the chromatophores of at least two fish species, the mandarin fish and the picturesque dragonet.[31] More commonly, blueness in animals is a structural colouration; an optical interference effect induced by organized nanometer-sized scales or fibres. Examples include the plumage of several birds like the blue jay and indigo bunting,[32] the scales of butterflies like the morpho butterfly,[33] collagen fibres in the skin of some species of monkey and opossum,[34] and the iridophore cells in some fish and frogs.[35][36]

Eyes

Blue eyes do not actually contain any blue pigment. Eye colour is determined by two factors: the pigmentation of the eye's iris[37][38] and the scattering of light by the turbid medium in the stroma of the iris.[39] In humans, the pigmentation of the iris varies from light brown to black. The appearance of blue, green, and hazel eyes results from the Tyndall scattering of light in the stroma, an optical effect similar to what accounts for the blueness of the sky.[39][40] The irises of the eyes of people with blue eyes contain less dark melanin than those of people with brown eyes, which means that they absorb less short-wavelength blue light, which is instead reflected out to the viewer. Eye colour also varies depending on the lighting conditions, especially for lighter-coloured eyes.

Blue eyes are most common in Ireland, the Baltic Sea area and Northern Europe,[41] and are also found in Eastern, Central, and Southern Europe. Blue eyes are also found in parts of Western Asia, most notably in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and Iran.[42] In Estonia, 99% of people have blue eyes.[43][44] In Denmark in 1978, only 8% of the population had brown eyes, though through immigration, today that number is about 11%.[44] In Germany, about 75% have blue eyes.[44]

In the United States, as of 2006, one out of every six people, or 16.6% of the total population, and 22.3% of the white population, have blue eyes, compared with about half of Americans born in 1900, and a third of Americans born in 1950. Blue eyes are becoming less common among American children[citation needed]. In the US, boys are 3–5 per cent more likely to have blue eyes than girls.[41]

History

In the ancient world

Lapis lazuli bowl from Iran, end of 3rd – beginning of 2nd millennium BC (Louvre Museum)

Egyptian blue tripodic beaker imitating lapis lazuli. South Mesopotamia. (1399-1200 BC)

Fresco of Polyphemus and Galatea, Pompei, using Egyptian blue (1st c. BC) (Metropolitan Museum)

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mines,[45] in Shortugai, and in other mines in Badakhshan province in northeast Afghanistan.[46]

Lapis lazuli artifacts, dated to 7570 BC, have been found at Bhirrana, which is the oldest site of Indus Valley civilisation.[47] Lapis was highly valued by the Indus Valley Civilisation (7570–1900 BC).[47][48][49] Lapis beads have been found at Neolithic burials in Mehrgarh, the Caucasus, and as far away as Mauritania.[50] It was used in the funeral mask of Tutankhamun (1341–1323 BC).[51]

A term for Blue was relatively rare in many forms of ancient art and decoration, and even in ancient literature. The Ancient Greek poets described the sea as green, brown or "the colour of wine". The colour was not mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.[52] Reds, blacks, browns, and ochres are found in cave paintings from the Upper Paleolithic period, but not blue. Blue was also not used for dyeing fabric until long after red, ochre, pink, and purple. This is probably due to the perennial difficulty of making blue dyes and pigments. On the other hand, the rarity of blue pigment made it even more valuable.[53]

The earliest known blue dyes were made from plants – woad in Europe, indigo in Asia and Africa, while blue pigments were made from minerals, usually either lapis lazuli or azurite, and required more.[54] Blue glazes posed still another challenge since the early blue dyes and pigments were not thermally robust. In ca. 2500 BC, the blue glaze Egyptian blue was introduced for ceramics, as well as many other objects.[55][56] The Greeks imported indigo dye from India, calling it indikon, and they painted with Egyptian blue. Blue was not one of the four primary colours for Greek painting described by Pliny the Elder (red, yellow, black, and white). For the Romans, blue was the colour of mourning, as well as the colour of barbarians. The Celts and Germans reportedly dyed their faces blue to frighten their enemies, and tinted their hair blue when they grew old.[57] The Romans made extensive use of indigo and Egyptian blue pigment, as evidenced, in part, by frescos in Pompeii. The Romans had many words for varieties of blue, including caeruleus, caesius, glaucus, cyaneus, lividus, venetus, aerius, and ferreus, but two words, both of foreign origin, became the most enduring; blavus, from the Germanic word blau, which eventually became bleu or blue; and azureus, from the Arabic word lazaward, which became azure.[58]

Blue was widely used in the decoration of churches in the Byzantine Empire.[59] By contrast, in the Islamic world, blue was of secondary to green, believed to be the favourite colour of the Prophet Mohammed. At certain times in Moorish Spain and other parts of the Islamic world, blue was the colour worn by Christians and Jews, because only Muslims were allowed to wear white and green.[60]

In the Middle Ages

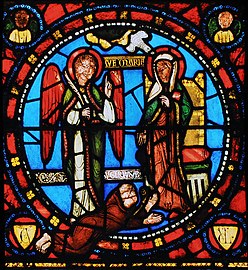

Stained glass window at Saint Denis Basilica (1130-1140), coloured with cobalt blue

Detail of the Blue Virgin Window, Chartres Cathedral (12th c.)

The Wilton Diptych (1395–1399). The Virgin Mary was traditionally shown in blue(14th c.)

In the art and life of Europe during the early Middle Ages, blue played a minor role. This changed dramatically between 1130 and 1140 in Paris, when the Abbe Suger rebuilt the Saint Denis Basilica. Suger considered that light was the visible manifestation of the Holy Spirit.[61] He installed stained glass windows coloured with cobalt, which, combined with the light from the red glass, filled the church with a bluish violet light. The church became the marvel of the Christian world, and the colour became known as the "bleu de Saint-Denis". In the years that followed even more elegant blue stained glass windows were installed in other churches, including at Chartres Cathedral and Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.[62]

In the 12th century the Roman Catholic Church dictated that painters in Italy (and the rest of Europe consequently) to paint the Virgin Mary with blue, which became associated with holiness, humility and virtue. In medieval paintings, blue was used to attract the attention of the viewer to the Virgin Mary. Paintings of the mythical King Arthur began to show him dressed in blue. The coat of arms of the kings of France became an azure or light blue shield, sprinkled with golden fleur-de-lis or lilies. Blue had come from obscurity to become the royal colour.[63]

Renaissance through 18th century

Blue came into wider use beginning in the Renaissance, when artists began to paint the world with perspective, depth, shadows, and light from a single source. In Renaissance paintings, artists tried to create harmonies between blue and red, lightening the blue with lead white paint and adding shadows and highlights. Raphael was a master of this technique, carefully balancing the reds and the blues so no one colour dominated the picture.[64]

Ultramarine was the most prestigious blue of the Renaissance, being more expensive than gold. Wealthy art patrons commissioned works with the most expensive blues possible. In 1616 Richard Sackville commissioned a portrait of himself by Isaac Oliver with three different blues, including ultramarine pigment for his stockings.[65]

Delftware plaque with cobalt blue painting (1683) (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Urn by Josiah Wedgewood (1780s) (Metropolitan Museum)

"Girl with a Pearl Earring" by Johannes Vermeer features ultramarine pigment

An industry for the manufacture of fine blue and white pottery began in the 14th century in Jingdezhen, China, using white Chinese porcelain decorated with patterns of cobalt blue, imported from Persia. It was first made for the family of the Emperor of China, then was exported around the world, with designs for export adapted to European subjects and tastes. The Chinese blue style was also adapted by Dutch craftsmen in [Delft and English craftsmen in Staffordshire in the 17th-18th centuries. in the 18th century, blue and white porcelains were produced by Josiah Wedgwood and other British craftsmen.[66]

19th-20th century

Beau Brummel (1776-1840) introduced the ancestor of the modern blue suit

The early 19th century saw the ancestor of the modern blue business suit, created by Beau Brummel (1776-1840), who set fashion at the London Court. It also saw the invention of blue jeans, a highly popular form of workers's costume, invented in 1853 by Jacob W. Davis who used metal rivets to strengthen blue denim work clothing in the California gold fields. The invention was funded by San Francisco entrepreneur Levi Strauss, and spread around the world.[67]

Van Gogh's Starry Night Over the Rhône (1888). Blue used to create a mood or atmosphere. A cobalt blue sky, and cobalt or ultramarine water.

- Old guitarist chicago.jpg

Blue conveys melancholy in Picasso's The Old Guitarist (1903-1904).

- Matisse Conversation.jpg

"The Conversation" by Henri Matisse (1908-1912)

Recognizing the emotional power of blue, many artists made it the central element of paintings in the 19th and 20th centuries. They included Pablo Picasso, Pavel Kuznetsov and the Blue Rose art group, and Kandinsky and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) school.[68] Henri Matisse expressed deep emotions with blue:, "A certain blue penetrates your soul."[69] In the second half of the 20th century, painters of the abstract expressionist movement use blues to inspire ideas and emotions. Painter Mark Rothko observed that colour was "only an instrument;" his interest was "in expressing human emotions tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on."[70]

In society and culture

Uniforms

Officers of the London Metropolitan Police

Sailors of the Royal Navy

In the 17th century. The Prince-Elector of Brandenburg, Frederick William I of Prussia, chose Prussian blue as the new colour of Prussian military uniforms, because it was made with Woad, a local crop, rather than Indigo, which was produced by the colonies of Brandenburg's rival, England. It was worn by the German army until World War I, with the exception of the soldiers of Bavaria, who wore sky-blue.[71]

In 1748, the Royal Navy adopted a dark shade of blue for the uniform of officers.[67] It was first known as marine blue, now known as navy blue.[72] The militia organized by George Washington selected blue and buff, the colours of the British Whig Party. Blue continued to be the colour of the field uniform of the US Army until 1902, and is still the colour of the dress uniform.[73]

In the 19th century, police in the United Kingdom, including the Metropolitan Police and the City of London Police also adopted a navy blue uniform. Similar traditions were embraced in France and Austria.[74] It was also adopted at about the same time for the uniforms of the officers of the New York City Police Department.[67]

Religion

Blue domes of the Church dedicated to St. Spirou in Firostefani, Santorini island (Thira), Greece.

Persian blue in Shah mosque (16th c.) in Isfahan, Iran

The flag of Israel uses a special variety of blue, called tekhelet

- Blue in Judaism: In the Torah,[75] the Israelites were commanded to put fringes, tzitzit, on the corners of their garments, and to weave within these fringes a "twisted thread of blue (tekhelet)".[76] In ancient days, this blue thread was made from a dye extracted from a Mediterranean snail called the hilazon. Maimonides claimed that this blue was the colour of "the clear noonday sky"; Rashi, the colour of the evening sky.[77] According to several rabbinic sages, blue is the colour of God's Glory.[78] Staring at this colour aids in mediation, bringing us a glimpse of the "pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity", which is a likeness of the Throne of God.[79] (The Hebrew word for glory.) Many items in the Mishkan, the portable sanctuary in the wilderness, such as the menorah, many of the vessels, and the Ark of the Covenant, were covered with blue cloth when transported from place to place.[80]

- Blue in Christianity: Blue is particularly associated with the Virgin Mary. This was the result of a decree of Pope Gregory I (540-601) who ordered that all religious paintings should tell a story which was clearly comprehensible to all viewers, and that figures should be easily recognizable, especially that of the figure of Mary. If she was alone in the image, her costume was usually painted with the finest blue, ultramarine. If she was with Christ, her costume was usually painted with a less expensive pigment, to avoid outshining him.[81][82][83][84]

- Blue in Hinduism: Many of the gods are depicted as having blue-coloured skin, particularly those associated with Vishnu, who is said to be the preserver of the world, and thus intimately connected to water. Krishna and Rama, Vishnu's avatars, are usually depicted with blue skin. Shiva, the destroyer deity, is also depicted in a light-blue hue, and is called neela kantha, or blue-throated, for having swallowed poison to save the universe during the Samudra Manthana, the churning of the ocean of milk. Blue is used to symbolically represent the fifth, and the throat, chakra (Vishuddha).[85]

- Blue in Sikhism: The Akali Nihangs warriors wear all-blue attire. Guru Gobind Singh also has a blue roan horse. The Sikh Rehat Maryada states that the Nishan Sahib hoisted outside every Gurudwara should be xanthic (Basanti in Punjabi) or greyish blue (modern day navy blue) (Surmaaee in Punjabi) colour.[86][87]

- Blue in Paganism: Blue is associated with peace, truth, wisdom, protection, and patience. It helps with healing, psychic ability, harmony, and understanding.[88]

Sports

In sports, blue is widely represented in uniforms in part because the majority of national teams wear the colours of their national flag. For example, the World Cup-winning France are known as Les Bleus (the Blues). Similarly, Argentina, Italy, and Uruguay wear blue shirts.[89] The Asian Football Confederation and the Oceania Football Confederation use blue text on their logos. Blue is well represented in baseball (Blue Jays, basketball, and American football, and Ice hockey. The Indian national cricket team wears blue uniform during One day international matches, as such the team is also referred to as "Men in Blue".[90]

Politics

Flag of the United Nations, approximates "sky blue"

Flag of the European Union is "reflex blue", a medium dark blue

Unlike red or green, blue was not strongly associated with any particular country, religion or political movement. As the colour of harmony, it was chosen as the colour for the flags of the United Nations, the European Union, and NATO.[91]

In politics, blue is sometimes used as the colour of conservative parties, contrasting with the red of more leftist parties.[92] It is the colour of the British Conservative party. However, in the United States, the colours are reversed. To avoid associations of the Democrats with socialism or the far left, States which voted Democratic in four consecutive presidential elections are termed "blue states", while those which voted for Republicans are termed "red states".[93] States which voted for different parties in two of the last four presidential elections are called "Swing States", and are usually coloured purple, a mix of red and blue, or sometimes pink or light blue.[94]

See also

References

- ^ "CSS Color Module Level 3". w3.org. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010.

- ^ Defonseka, Chris (20 May 2019). Polymeric Composites with Rice Hulls: An Introduction. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-064320-6.

- ^ Michel Pastoureau, Bleu – Histoire d'une couleur

- ^ a b Heller 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary (1970).

- ^ Friar, Stephen, ed. (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks/A&C Black. pp. 40, 343. ISBN 978-0-906670-44-6.

- ^ a b Tim Howard (20 May 2012). "Why Isn't the Sky Blue?". Radiolab at WNYC Studios (Podcast). Linguist: Guy Deutscher; Professor: Jules Davidoff. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Wavelength of Blue and Red Light". Center for Science Education. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "The Science of Color". library.si.edu. 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Arthur C. Hardy and Fred H. Perrin. The Principles of Optics. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York. 1932.

- ^ Sandra Espinet. "Glossary Term: Color wheel". Sanford-artedventures.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Laserglow – Blue, Red, Yellow, Green Lasers". Laserglow.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ "Laserglow – Optogenetics". Laserglow.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ "Iridescence in Lepidoptera". Natural Photonics (originally in Physics Review Magazine). University of Exeter. September 1998. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Michel Pastoureau, Bleu – HIstoire d'une couleur, pp. 114–16

- ^ Roger Keyes, Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, R, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, 1984, p. 42, plate #140, p. 91 and catalogue entry #439, p. 185. for more on the story of Prussian blue in Japanese prints, see also the website of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

- ^ Maerz and Paul (1930). A Dictionary of Color New York: McGraw Hill p. 206

- ^ "Eight blue moments in art history". The Tate. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d Newsome, Andrew G.; Culver, Catherine A.; Van Breemen, Richard B. (2014). "Nature's Palette: The Search for Natural Blue Colorants". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (28): 6498–6511. doi:10.1021/jf501419q. PMID 24930897.

- ^ Placke, Mina; Fischer, Norbert; Colditz, Michael; Kunkel, Ernst; Bohne, Karl-Heinz (2016). "Drawing and Writing Materials". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_037.pub2. ISBN 9783527306732.

- ^ "Why is the sky Blue?". ucr.edu. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015.

- ^ Glenn S. Smith (July 2005). "Human color vision and the unsaturated blue color of the daytime sky" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 73 (7): 590–597. Bibcode:2005AmJPh..73..590S. doi:10.1119/1.1858479. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2011.

Near sunrise and sunset, most of the light we see comes in nearly tangent to the Earth's surface, so that the light's path through the atmosphere is so long that much of the blue and even green light is scattered out, leaving the sun rays and the clouds it illuminates red. Therefore, when looking at the sunset and sunrise, the colour red is more perceptible than any of the other colours.

- ^ Anne Marie Helmenstine. "Why Is the Ocean Blue?". About.com Education. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Harmon, A. D.; Weisgraber, K. H.; Weiss, U. (1980). "Preformed azulene pigments of Lactarius indigo (Schw.) Fries (Russulaceae, Basidiomycetes)". Experientia. 36: 54–56. doi:10.1007/BF02003967. S2CID 21207966.

- ^ Nuno Mateas, Victor de Freitas (2008). "Anthrocyanins as Food Colorants". In Gould, K.; Davies, K.; Winefield, C. (eds.). Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications. Springer. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-387-77334-6.

- ^ Umbers, Kate D. L. (2013). "On the Perception, Production and Function of Blue Colouration in Animals". Journal of Zoology. 289 (4): 229–242. doi:10.1111/jzo.12001.

- ^ Vane-Wright, Richard I. (22 February 1979). "The coloration, identification and phylogeny of Nessaea butterflies (Lepidoptera : Nymphalidae)". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Entomology Series. 38 (2): 27–56. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Simonis, Priscilla; Serge, Berthier (30 March 2012). "Chapter number 1 How Nature produces blue color". In Massaro, Alessandro (ed.). Photonic Crystals - Introduction, Applications and Theory. InTech. ISBN 978-953-51-0431-5. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Goda, Makoto; Fujii, Ryozo (1995). "Blue Chromatophores in Two Species of Callionymid Fish". Zoological Science. 12 (6): 811–813. doi:10.2108/zsj.12.811. S2CID 86385679.

- ^ "How Birds Make Colorful Feathers". 11 August 2015.

- ^ Potyrailo, Radislav A.; Bonam, Ravi K.; Hartley, John G.; Starkey, Timothy A.; Vukusic, Peter; Vasudev, Milana; Bunning, Timothy; Naik, Rajesh R.; Tang, Zhexiong; Palacios, Manuel A.; Larsen, Michael; Le Tarte, Laurie A.; Grande, James C.; Zhong, Sheng; Deng, Tao (2015). "Towards outperforming conventional sensor arrays with fabricated individual photonic vapour sensors inspired by Morpho butterflies". Nature Communications. 6: 7959. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.7959P. doi:10.1038/ncomms8959. PMC 4569698. PMID 26324320.

- ^ Prum RO, Torres RH (May 2004). "Structural Colouration of Mammalian Skin: Convergent Evolution of Coherently Scattering Dermal Collagen Arrays" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 207 (Pt 12): 2157–2172. doi:10.1242/jeb.00989. hdl:1808/1599. PMID 15143148. S2CID 8268610. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Ariel Rodríguez; Nicholas I. Mundy; Roberto Ibáñez; Heike Pröhl (2020). "Being red, blue and green: the genetic basis of coloration differences in the strawberry poison frog (Oophaga pumilio)". BMC Genomics. 21 (1): 301. doi:10.1186/s12864-020-6719-5. PMC 7158012. PMID 32293261.

- ^ Makoto Goda; Ryozo Fujii (1998). "The Blue Coloration of the Common Surgeonfish, Paracanthurus hepatus—II. Color Revelation and Color Changes". Zoological Science. 15 (3): 323–333. doi:10.2108/zsj.15.323. PMID 18465994. S2CID 5860272.

- ^ Wielgus AR, Sarna T (2005). "Melanin in human irides of different color and age of donors". Pigment Cell Res. 18 (6): 454–64. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00268.x. PMID 16280011.

- ^ Prota G, Hu DN, Vincensi MR, McCormick SA, Napolitano A (1998). "Characterization of melanins in human irides and cultured uveal melanocytes from eyes of different colors". Exp. Eye Res. 67 (3): 293–99. doi:10.1006/exer.1998.0518. PMID 9778410.

- ^ a b Fox, Denis Llewellyn (1979). Biochromy: Natural Coloration of Living Things. University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-520-03699-4. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015.

- ^ Mason, Clyde W. (1924). "Blue Eyes". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 28 (5): 498–501. doi:10.1021/j150239a007.

- ^ a b Douglas Belkin (17 October 2006). "Don't it make my blue eyes brown Americans are seeing a dramatic color change". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012.

- ^ "Pigmentation, the Pilous System, and Morphology of the Soft Parts". altervista.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011.

- ^ statement by Hans Eiberg from the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at the University of Copenhagen

- ^ a b c Weise, Elizabeth (5 February 2008). "More than meets the blue eye: You may all be related". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ David Bomford and Ashok Roy, A Closer Look- Colour (2009), National Gallery Company, London, (ISBN 978-1-85709-442-8)

- ^ Moorey, Peter Roger (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: the Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- ^ a b "Excavation Bhirrana | ASI Nagpur". excnagasi.in. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Sarkar, Anindya; Mukherjee, Arati Deshpande; Bera, M. K.; Das, B.; Juyal, Navin; Morthekai, P.; Deshpande, R. D.; Shinde, V. S.; Rao, L. S. (25 May 2016). "Oxygen isotope in archaeological bioapatites from India: Implications to climate change and decline of Bronze Age Harappan civilization". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 26555. Bibcode:2016NatSR...626555S. doi:10.1038/srep26555. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4879637. PMID 27222033. S2CID 4425978.

- ^ DIKSHIT, K.N. (2012). "The Rise of Indian Civilization: Recent Archaeological Evidence from the Plains of 'Lost' River Saraswati and Radio-Metric Dates". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 72/73: 1–42. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 43610686.

- ^ Bowersox & Chamberlin 1995

- ^ Alessandro Bongioanni & Maria Croce

- ^ Varichon 2005, p. 161-164.

- ^ See Pastoureau 2000, pp. 13–17.

- ^ Moorey, Peter Roger (1999). Ancient mesopotamian materials and industries: the archaeological evidence. Eisenbrauns. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- ^ Chase, W.T. 1971, "Egyptian blue as a pigment and ceramic material." In: R. Brill (ed.) Science and Archaeology. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-02061-0

- ^ J. Baines, "Color Terminology and Color Classification in Ancient Egyptian Color Terminology and Polychromy", in The American Anthropologist, volume 87, 1985, pp. 282–97.

- ^ Caesar, The Gallic Wars, V., 14, 2. Cited by Miche Pastourou, p. 178.

- ^ Pastoureau 2000, p. 26.

- ^ L. Brehier, Les mosaiques a fond d'azur, in Etudes Byzantines, volume III, Paris, 1945. pp. 46ff.

- ^ Varichon 2005, p. 175.

- ^ Lours, Mathieu, "Le Vitrail", Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot, Paris (2021)

- ^ Pastoureau 2000, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Pastoureau 2000, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Ball 2001, p. 165.

- ^ Travis, Time, "The Victoria and Albert Book of Colour Design" (2020), p. 185

- ^ Travis, Tim, "The Victoria and Albert Museum Book of Colour in Design" (2020), p. 200-201

- ^ a b c Heller (2010) p.32

- ^ Wassily Kandinsky, M. T. Sadler (Translator) Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Dover Publ. (Paperback). 80 pp. ISBN 0-486-23411-8.

- ^ "Un certain bleu pénètre votre âme." Cited in Riley 1995.

- ^ Mark Rothko 1903–1970. Tate Gallery Publishing, 1987.

- ^ Heller (2010) p.31

- ^ J.R. Hill, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ^ Walter H. Bradford. "Wearing Army Blue: a 200-year Tradition". army.mil. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014.

- ^ Jean Tulard, Jean-François Fayard, Alfred Fierro, Histoire et dictionnaire de la Révolution française, 1789–1799, Éditions Robert Laffont, collection Bouquins, Paris, 1987. ISBN 2-7028-2076-X

- ^ Numbers 15:38.

- ^ Tekhelet.com Archived 30 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, the Ptil Tekhelet Organization

- ^ Mishneh Torah, Tzitzit 2:1; Commentary on Numbers 15:38.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 14:3; Hullin 89a.

- ^ Exodus 24:10; Ezekiel 1:26; Hullin 89a.

- ^ Numbers 4:6–12.

- ^ Heller, "Psychologie de la Colour - Effets et Symboliques", (2009),p. 32

- ^ "Your question answered". udayton.edu. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- ^ "The Spirit of Notre Dame". Nd.edu. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ "Board Question #31244 | The 100 Hour Board". Theboard.byu.edu. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ Stevens, Samantha. The Seven Rays: a Universal Guide to the Archangels. Toronto: Insomniac Press, 2004. ISBN 1-894663-49-7. p. 24.

- ^ Sikh Rehat Maryada: Section Three, Chapter IV, Article V, r.

- ^ "Nishan Sahib Khanda Sikh Symbols Sikh Museum History Heritage Sikhs". www.sikhmuseum.com.

- ^ "Magical Properties of Colors". Wicca Living. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ "FIFA World Cup 2010 – Historical Football Kits". Historicalkits.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ "This Is The Reason Why Indian Cricket Team Wears A Blue Jersey During ODIs". 3 July 2016.

- ^ Heller, "Psychologie de la Couleur" pp. 36-37

- ^ "Why is the Conservative Party blue?". BBC News. 20 April 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Battaglio, Stephen (3 November 2016). "When red meant Democratic and blue was Republican. A brief history of TV electoral maps". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "What Are Swing States and How Did They Become a Key Factor in US Elections? – HISTORY". www.history.com. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

Works cited

- Ball, Philip (2001). Bright Earth, Art, and the Invention of Colour. London: Penguin Group. p. 507. ISBN 978-2-7541-0503-3. (page numbers refer to the French translation)

- Bowersox, Gary W.; Chamberlin, Bonita E. (1995). Gemstones of Afghanistan. Tucson, AZ: Geoscience Press.

- Heller, Eva (2009). Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques (in French). Munich: Pyramyd. ISBN 978-2-35017-156-2.

- Pastoureau, Michel (2000). Bleu: Histoire d'une couleur (in French). Paris: Editions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-086991-1.

- Riley, Charles A., II (1995). Color Codes: Modern Theories of Color in Philosophy, Painting and Architecture, Literature, Music, and Psychology. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England.

- Travis, Tim (2020). The Victoria and Albert Museum Book of Colour in Design. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-48027-4.

- Varichon, Anne (2005). Couleurs : pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples (in French). Paris: Editions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-084697-4.

- Lours, Mathieu (2020). Le Vitrai. Éditions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-755-80845-2.

Further reading

- Balfour-Paul, Jenny (1998). Indigo. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1776-8.

- Josserand, M.; Meeussen, E.; Majid, A. (27 September 2021). "Environment and culture shape both the colour lexicon and the genetics of colour perception". Sci Rep. Nature. 11 (19095): 19095. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1119095J. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-98550-3. PMC 8476573. PMID 34580373. S2CID 238202924. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- Macdonald, Fiona (7 April 2018). "There's Evidence Humans Didn't Actually See Blue Until Modern Times". Science Alert. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- Mollo, John (1991). Uniforms of The American Revolution in Color. Illustrated by Malcolm McGregor. New York: Stirling Publications. ISBN 978-0-8069-8240-3.

External links

The dictionary definition of blue at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of blue at Wiktionary Media related to blue at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to blue at Wikimedia Commons- "Friday essay: from the Great Wave to Starry Night, how a blue pigment changed the world", By Dr Hugh Davies, theconversation.com

- Articles with missing files

- CS1: long volume value

- Articles containing French-language text

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Use dmy dates from October 2022

- EngvarB from October 2017

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Pages using infobox color with deprecated parameters

- Use British English from June 2021

- Articles containing Middle English (1100-1500)-language text

- Articles containing Old French (842-ca. 1400)-language text

- Articles containing Old High German (ca. 750-1050)-language text

- Articles containing Russian-language text

- Articles containing Spanish-language text

- Articles containing Vietnamese-language text

- Articles containing Japanese-language text

- Articles containing Lakota-language text

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements

- Articles containing Latin-language text

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- Commons category link is defined as the pagename

- Shades of blue

- AC with 0 elements

- Primary colors

- Secondary colors

- Optical spectrum

- Rainbow colors

- Web colors

![Prussian blue, FeIII 4[FeII (CN) 6] 3, is the blue of blueprints.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Prussian_blue.jpg/684px-Prussian_blue.jpg)

![The Blue Boy (1770), featuring lapis lazuli, indigo, and cobalt colourants,[19]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/The_Blue_Boy.jpg/203px-The_Blue_Boy.jpg)

![Lactarius indigo[26]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Lactarius_indigo_48568_edit.jpg/300px-Lactarius_indigo_48568_edit.jpg)