BioArt

BioArt is an art practice where artists work with biology, live tissues, bacteria, living organisms, and life processes. Using scientific processes and practices such as biology and life science practices, microscopy, and biotechnology (including technologies such as genetic engineering, tissue culture, and cloning) the artworks are produced in laboratories, galleries, or artists' studios. The scope of BioArt is a range considered by some artists to be strictly limited to "living forms", while other artists include art that uses the imagery of contemporary medicine and biological research, or require that it address a controversy or blind spot posed by the very character of the life sciences.[1]

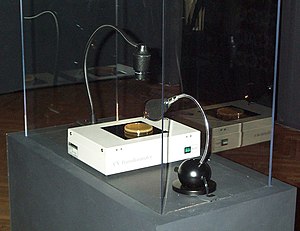

Bioart originated at the end of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century.Although BioArtists work with living matter, there is some debate as to the stages at which matter can be considered to be alive or living. Creating living beings and practicing in the life sciences brings about ethical, social, and aesthetic inquiry. The phrase "BioArt" was coined by Eduardo Kac in 1997 in relation to his artwork Time Capsule. Symbiotica developed one of the earlier art/science laboratories for artists interested in working with BioArt methods and technologies.[2]

Overview

BioArt is often intended to highlight themes and beauty in biological subjects, address or question philosophical notions or trends in science, and can at times be shocking or humorous. One survey of the field, Isotope: A Journal of Literary Science and Nature Writing, puts it this way: "BioArt is often ludicrous. It can be lumpy, gross, unsanitary, sometimes invisible, and tricky to keep still on the auction block. But at the same time, it does something very traditional that art is supposed to do: draw attention to the beautiful and grotesque details of nature that we might otherwise never see."[3]

While raising questions about the role of science in society, "most of these works tend toward social reflection, conveying political and societal criticism through the combination of artistic and scientific processes."[4]

While most people who practice BioArt are categorized as artists in this new media, they can also be seen as scientists, since the actual medium within a work pertains to molecular structures, and so forth.[5]

Artists in laboratories

The laboratory work can pose a challenge to the artist, at first, as the environment is often foreign to the artist. While some artists have prior scientific training, others must be trained to perform the procedures or work in tandem with scientists who can perform the tasks that are required. Bio artists often use formations relating to or engaging with science and scientific practices, such as working with bacteria or live tissue.[citation needed]

In 2000, Eduardo Kac commissioned the creation of a transgenic GFP bunny as part of a piece called GFP Bunny. "The PR campaign included a picture of Kac holding a white rabbit and another, iconic image of a rabbit photographically enhanced to appear green."[6]

In 2003, The Tissue Culture & Art Project in collaboration with Stelarc grew a 1/4 scale replica of an ear using human cells to create the Extra Ear project. The project was carried out at Symbiotica: the Art & Science Collaborative Research Laboratory, School of Anatomy and Human Biology, University of Western Australia. [7]

In 2006, Marc Stelarc had the first of two experimental surgeries to have his “Ear On Arm” implanted. The second surgery was to implant a microphone in the implanted ear so it could hear. The implanted ear then projects the sound to other parts of the world, so people could listen into what the ear on arm was hearing. He has connected it to the internet, which further connects his bio to technology but also opens the possibility of being hacked. The project took over 12 years.[8] [9] [10]

In 2015-2016 Amy Karle created Regenerative Reliquary, a sculpture of bio-printed scaffolds for human MSC stem cell culture into bone, in the shape of a human hand form installed in a bioreactor. She created the initial versions of this piece in collaboration with scientists, bioscientists, material scientists and technologists. [11] [12] In 2019, she created a biomechanical sculpture in the form of a beating human heart placed on exhibition in Japan where there was historically great controversy surrounding organ transplant, specifically cardiac transplants, see Organ transplantation in Japan. The bioartwork proposes a redesigned vascular system with the potential to enhance heart function, and the potential to grow replacement organs in a lab as opposed to using human or other animal transplants, while questioning the implications of enhancement on what it means to be human and impacts on evolution.[13] [14][15] She has used 3D printing using biocompatible polyamide.[16][17]

Art addressing topics in biology and society

The scope of the term BioArt is a subject of ongoing debate. The primary point of debate centers around whether BioArt must necessarily involve manipulation of biological material, as is the case in microbial art which by definition is made of microbes. A broader definition of the term would include work that addresses the social and ethical considerations of the biological sciences.[18] Under these terms BioArt as a genre has many crossovers with fields such as critical or speculative design.[19] This type of work often reaches a much broader general audience, and is focused on starting discussions in this space, rather than pioneering or even using specific biological practices. Examples in this space include Ray Fish shoes, which advertised shoes made and patterned with genetically engineered stingray skin,[20] BiteLabs, a biotech startup that attempted to make salami out of meat cultured from celebrity tissue samples,[21] and Ken Rinaldo's Augmented Fish Reality, an installation of five rolling robotic fish-bowl sculptures controlled by Siamese Fighting Fish.[22]

Controversy

Artworks that use living materials created with scientific processes and biotechnology in itself brings up many ethical questions and concerns.[23] [24] Wired magazine has reported that the "emerging field of "bioart" can be extremely provocative, and brings with it a range of technical, logistical and ethical issues."[2] Bioart practitioners can and have at times aided the advancement of scientific research and researchers in the process of creating their work; however, bioart and bioartists can also cross into controversy by challenging scientific thinking, by working with controversial human or animal material, or by releasing invasive species, as they are not regulated to adhere to standards, including biosafety or biosecurity. [25] [26] [27]

Another big issue are the dangers that come from errors and fringe activities that could occur through creating in non-regulated or not completely safe lab spaces, DIYbio, biohacking, and bioterrorism. One of the most publicized instances of a non-scientist being arrested for suspected “bioterrorism” was the case of artist Steve Kurtz, a founding member of Critical Art Ensemble (arrest in 2004, bioterrorism charges never brought). [28] He was investigated by the FBI for four years and culminated with him being indicated for mail and wire fraud for obtaining a strain of bacteria commonly used in school lab experiments. He was planning on using that bacteria in a project critiquing the United States. His bioart work was considered pioneering in politically engaged art, biotechnology and ecological struggle. [29] [30] [31] The ordeal became the subject of a book and a film. [32] [33]

BioArt has been scrutinized and criticized as it may lack ethical oversight. USA Today reported that animal rights groups accused Kac and others of using animals unfairly for their own personal gain, and conservative groups question the use of transgenic technologies and tissue-culturing from a moral standpoint.[4]

Alka Chandna, a senior researcher with PETA in Norfolk, Virginia, has stated that using animals for the sake of art is no different from using animal fur for clothing material. "Transgenic manipulation of animals is just a continuum of using animals for human end, regardless of whether it is done to make some sort of sociopolitical critique. The suffering and exacerbation of stress on the animals is very problematic."[4]

However, many BioArt projects deal with the manipulation of cells and not whole organisms, such as Victimless Leather by Symbiotica. "An actualized possibility of wearing 'leather' without killing an animal is offered as a starting point for cultural discussion. Our intention is not to provide yet another consumer product, but rather to raise questions about our exploitation of other living beings."[34]

Notable exhibitions of bioart

Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria and the Ars Electronica Festival was an early adaptor of exhibiting and promoting bioart, and continues to be a pioneer of sharing and promoting bioart, life projects, and bioartists.[35] Their long-standing Prix Ars Electronica award which exhibits and honors artists in various media categories [36] includes categories of hybrid arts and life art encompassing bioart.

In 2016, The Beijing Media Art Biennale's Theme was "Ethics of Technology"[37] and in 2018 it was "<Post-Life>". The Biennale is held at the CAFA Museum in Beijing, China and includes major works in biological arts, with thematic exhibitions. The 2018 Bienalle included international artworks relevant to the thematic topics of “Data Life”, “Mechanical Life” and “Synthesized Life” and a Lab Space exhibition area that focused on showcasing international laboratory practice in art and technology. [38] [39] [40]

The Centre Pompidou in Paris, France presented La Fabrique Du Vivant, "The Fabric of the Living" in 2019, a group exhibition of living and artificial life with recent work of artists, designers, and research from scientific laboratories. The artworks question the links between the living and the artificial, as well as the processes of artificial recreation of life; the manipulation of chemical procedures on living matter; self-generating works with ever-changing forms; hybrid works of organic matter and industrial material, or the hybridization of human and plant cells. In this era of digital technologies, artists draw on the world of biology, developing new social and political environments based on issues of those living in this era. [41]

The Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, Japan Future and the Arts: AI, Robotics, Cities, Life - How Humanity Will Live Tomorrow in 2019-2020 [42] This was a group exhibition that included a "bio atelier" with bioartworks from prominent bioartists across the world. One of the curatorial goals was to evoke the contemplation – through the latest scientific and technological developments in fields such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, robotics and augmented reality used in art, design, and architecture – of how human beings, their lives, and the environmental issues may look in the imminent future because of these developments. [43] [44]

See also

- Computer art

- Cyberarts

- Digital art

- Ecological art

- Electronic art

- Environmental art

- Evolutionary art

- Genetic art

- Hybrid arts

- Internet art

- Land art

- Neuroaesthetics

- New Media art

References

- ^ Pentecost, Claire (2008). "Outfitting the Laboratory of the Symbolic: Toward a Critical Inventory of Bioart". In Beatrice, da Costa (ed.). Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism and Technoscience. The MIT Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-262-04249-9.

- ^ a b Solon, Olivia (28 July 2011). "Bioart: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Using Living Tissue as a Medium". Wired. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ The Art is Alive

- ^ a b c Pasko, Jessica M. (2007-03-05). "Bio-artists use science to create art". USA Today.

- ^ BIOart Archived October 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pentecost, Claire (2008). "Outfitting the Laboratory of the Symbolic: Toward a Critical Inventory of Bioart". In Beatrice, da Costa (ed.). Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism and Technoscience. The MIT Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-262-04249-9.

- ^ "Extra Ear 1/4 Scale". 15 December 2004.

- ^ "Stelarc — Making Art out of the Human Body". 10 November 2018.

- ^ Moore, Jack (14 August 2015). "Why This Australian Artist Has a Third Ear Casually Growing on His Arm". GQ. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (13 April 2009). "Artist gets an extra ear implanted into his arm". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Schnugg, Claudia (2019). Creating artscience collaboration : bringing value to organizations. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-030-04549-4. OCLC 1089014855.

- ^ "Artist Amy Karle is growing a human hand with 3D printed scaffolds and stem cells". 3ders.org. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "The woman creating art with human stem cells". BBC News.

- ^ "HP Collaborates with Amy Karle, Leading 3D Printing Artist and Futurist". press.hp.com. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ "Future and the Arts: AI, Robotics, Cities, Life - How Humanity Will Live Tomorrow". Mori Art Museum. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Open Access Remix". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Futurist Amy Karle Unlocks the Potential of Humanity's Future". Design-milk.com. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ See Bio Art entry in Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2007-2014. (subscription required)

- ^ Anker, Suzanne (2014). "The beginnings and the ends of Bio Art" (PDF). Artlink. 34 (3).

- ^ "The Rise and Fall or Rayfish Footwear - Next Nature Network". 19 December 2012.

- ^ "The Guy Who Wants to Sell Lab-Grown Salami Made of Kanye West Is "100% Serious"". 2014-02-26.

- ^ Prixars Electronica : 2004 CyberArts : international compendium Prix Ars Electronica : computer animation/visual effects, digital musics, interactive art, net vision, digital communities, u19, freestyle computing, the nest idea. Austria: Hatje Cantz. 2004. ISBN 9783775714938.

- ^ Vaage, Nora (2016). "What Ethics for Bioart?". Nanoethics. 10: 87–104. doi:10.1007/s11569-016-0253-6. PMC 4791467. PMID 27069514.

- ^ Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Jane Calvert, Pablo Schyfter, Alistair Elfick and Drew Endy. "Synthetic Aesthetics Investigating Synthetic Biology's Designs on Nature".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bioart: An introduction".

- ^ Gaymon Bennett, Nils Gilman, Anthony Stavrianakis & Paul Rabinow (2009). "From synthetic biology to biohacking: are we prepared?". Nature Biotechnology. 27 (12): 1109–1111. doi:10.1038/nbt1209-1109. PMID 20010587. S2CID 26343447. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schmidt, M (2008). "Diffusion of synthetic biology: a challenge to biosafety". Systems and Synthetic Biology. 2 (1–2): 1–6. doi:10.1007/s11693-008-9018-z. PMC 2671588. PMID 19003431.

- ^ "Critical Art Ensemble".

- ^ Mitchell, Robert E. "Bioart and the Vitality of Media". University of Washington Press. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Chatzichristodoulou, Maria; Jefferies, Janis, eds. (2016). "Performative Science in an Age of Specialization: The Case of Critical Art Ensemble". Interfaces of Performance. doi:10.4324/9781315589244. ISBN 9781317114611.

- ^ Hirsch, Robert. "The Strange Case of Steve Kurtz: Critical Art Ensemble and the Price of Freedom". ProQuest.

- ^ "Orfeo by Richard Powers, review".

- ^ "Richard Powers' new novel is based on the notorious Steve Kurtz case in Buffalo". Archived from the original on 2014-01-25.

- ^ "Victemless Leather".

- ^ "BioArt".

- ^ "Prix Ars Electronica".

- ^ "D SCHOOL CAFA".

- ^ "Cafa预告丨第二届北京媒体艺术双年展"后生命"9月5日即将登场!".

- ^ "Beijing Media Arts Biennale 2018".

- ^ ""后生命"——第二届北京媒体艺术双年展即将拉开帷幕".

- ^ "La Fabrique du vivant - « Mutations / Créations 3 »".

- ^ "Future and the Arts: AI, Robotics, Cities, Life - How Humanity Will Live Tomorrow".

- ^ Flores, Ana Paola (January 2020). "Biopolitics in Future and the Arts: AI, Robotic, Cities, Life - Tokyo Exhibition".

- ^ "Future and the Arts: AI, Robotics, Cities, Life - How Humanity Will Live Tomorrow".

Bibliography

- Anker, Suzanne, and Dorothy Nelkin. The Molecular Gaze: Art in the Genetic Age. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2004.

- Bök, Christian. The Xenotext: Book I. Coach House Books, 2015.

- Da Costa, Beatriz, and Kavita Philip (eds.). Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism, and Technoscience. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

- Gatti, Gianna Maria. The Technological Herbarium. Edited, translated from the Italian, and with a preface by Alan N. Shapiro. Berlin: Avinus Press, 2010. Online at alan-shapiro.com

- Gessert, George. Green Light: Toward an Art of Evolution. Cambridge: MIT Press/Leonardo Books, 2010. ISBN 978-0-262-01414-4.

- Hauser, Jens. "Bio Art - Taxonomy of an Etymological Monster." UCLA Art/Sci Center series, 2006. Online at [1]

- Hauser, Jens (ed.). sk-interfaces. Exploding borders - creating membranes in art, technology and society. Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84631-149-9.

- Kac, Eduardo.Telepresence and Bio Art. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-472-06810-4.

- Kac, Eduardo (ed.). Signs of Life: Bio Art and Beyond. Cambridge: MIT Press/Leonardo Books, 2007. ISBN 0-262-11293-0.

- Kaniarē, Asēmina, and Kathryn High. Institutional Critique to Hospitality: Bio Art Practice Now : A Critical Anthology, Grigoris publications, ISBN 9789606120190 2017.

- Nicole C. Karafyllis (ed.). Biofakte - Versuch über den Menschen zwischen Artefakt und Lebewesen. Paderborn: Mentis 2003. In German.

- Levy, Steven. "Best of Technology Writing 2007." Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007 (in conjunction with DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS) [2]

- Miah, Andy. (ed.). Human Futures: Art in an Age of Uncertainty. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84631-181-9.

- Mitchell, Rob. Bioart and the Vitality of Media. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-295-99008-8.

- Mitchell, Rob, Helen Burgess, and Phillip Thurtle. Biofutures: Owning Body Parts and Information. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008. Interactive DVD.

- Reichle, Ingeborg. Kunst aus dem Labor. Springer, 2005. In German.

- Sammartano, Paola. Electrophotographs and Photographs with Human Hair for Future Cloning. Sergio Valle Duarte Zoom Internacional, 1995.

- Savini, Mario. Arte transgenica: la vita è il medium. Connessioni. Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2018. (pub.09/2018, ISBN 978-883339-0680)

- Schnugg, Claudia. [3] Creating artscience collaboration : bringing value to organizations. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-030-04549-4. OCLC 108901485

- Simou Panagiota, Tiligadis Konstantinos, Alexiou Athanasios. Exploring Artificial Intelligence Utilizing BioArt, 9th Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations Conference, IFIP AICT 412, pp. 687–692, 2013, © IFIP International Federation for Information Processing 2013, Springer.

- Thacker, Eugene. "Aesthetic Biology, Biological Art." Contextin' Art (Fall Issue, 2003). Online at [4] Archived 2017-11-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Thacker, Eugene. The Global Genome - Biotechnology, Politics, and Culture (Massachusetts: MIT Press/Leonardo Books, 2006. pp. 305–320. ISBN 978-0-262-70116-7.

- Vita-More, Natasha. "Brave BioArt 2: Shedding the Bio, Amassing the Nano, and Cultivating Emortal Life." "Reviewing the Future" Summit, Montreal, Canada, Coeur des Sciences, University of Quebec, 2007. [5]

- Wilson, Stephen. "Art and Science Now: How scientific research and technological innovation are becoming key to 21st-century aesthetics." London, England: Thames and Hudson, 2012. ISBN 978-0-500-23868-4

- Zylinska, Johanna. Bioethics in the Age of New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press/Leonardo Books, 2009. ISBN 978-0-262-24056-7.