Baháʼí House of Worship

| Part of a series on the |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

A Bahá'í House of Worship or Bahá'í temple is a place of worship of the Baháʼí Faith. It is also referred to by the name Mashriqu'l-Adhkár, which is Arabic for "Dawning-place of the remembrance of God". Bahá'í Houses of Worship are open to both Bahá'ís and non-Bahá'ís for prayer and reflection. All Bahá'í Houses of Worship have a round, nine-sided shape and are surrounded by nine pathways leading outwards and nine gardens. Baháʼí scriptures envisage Houses of Worship surrounded by a number of dependencies dedicated to social, humanitarian, educational, and scientific pursuits, although no Bahá'í House of Worship has yet been built up to that extent. At present, most Bahá'í devotional meetings occur in individuals' homes or local Bahá'í centres rather than in Bahá'í Houses of Worship.

As of 2022[update], thirteen Bahá'í Houses of Worship have been completed around the world (including one that was later destroyed). Eight of the twelve that are currently standing are continental temples, of which two, the Lotus Temple and the Santiago Bahá'í Temple, have won numerous architectural awards. The other four standing Bahá'í Houses of Worship are local Houses of Worship. The construction of two national Houses of Worship is underway and the groundbreaking for a fifth local House of Worship has taken place. Furthermore, Bahá'í communities own over 120 properties intended for future Houses of Worship.

General description

Terminology

The Bahá'í House of Worship was first mentioned under the name Mashriqu'l-Adhkár (مشرق اﻻذكار; Arabic for "Dawning-place of the remembrance of God") in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, the book of laws of Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Bahá'í Faith.[1][2] Baháʼu'lláh used the term Mashriqu'l-Adhkár to refer to any building where people gathered to worship.[1][3] His son and successor, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, continued this general usage of the term but also described a more specific type of building using the same term,[3] which for instance he said must be round and nine-sided.[4] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's grandson and successor, Shoghi Effendi, wrote that the term Mashriqu'l-Adhkár should apply only to this latter, more specific type of building, and that Bahá'í centres used in most Bahá'í communities should be known instead as Haziratu'l-Quds.[3] Since then, Shoghi Effendi's more specific meaning of Mashriqu'l-Adhkár has persisted, and it is buildings of this type that are known in English as Bahá'í Houses of Worship or Bahá'í temples.[3]

Concept and purpose

A Bahá'í House of Worship is a place of worship of the Baháʼí Faith, where both Baháʼís and non-Baháʼís can express devotion to God.[5] Bahá'í literature states that a House of Worship should be built in each city and town.[6] The Bahá'í laws emphasize that the spirit of the House of Worship must be a gathering place where people of all religions may worship God without denominational restrictions.[6] According to Shoghi Effendi, a Bahá'í temple is a "silent teacher" of the Bahá'í Faith.[7]

Bahá'í literature also stipulates that the Houses of Worship be surrounded by a complex of humanitarian, educational, and charitable institutions such as schools, hospitals, homes for the elderly, universities, hostels, and other social and humanitarian institutions to serve the areas in which they stand.[6][3] Shoghi Effendi said the future interaction between the House of Worship and its dependencies could provide "the essentials of Bahá'í worship and service, both so vital to the regeneration of the world."[3] To date, only a few such dependencies have been built[2] and no Bahá'í House of Worship has had the full range of dependencies that are envisioned.[6][8] Shoghi Effendi also viewed the functions of the House of Worship as complementary to those of the Haziratu'l-Quds (commonly known as a Bahá'í centre), and said that it would be desirable if both these buildings were on the same site.[3] Bahá'í devotional meetings in most communities take place in homes or Bahá'í centres, but Elham Afnan notes that such activities "evoke the spirit" of a House of Worship with the goal that it can eventually beconstructed.[2]

Architecture

All Bahá'í temples share certain architectural elements, some of which are specified by Bahá'í scripture. All Bahá'í Houses of Worship are required to have a nine-sided shape (nonagon) and to have nine pathways lead outward and nine gardens surrounding them.[3] While as of 2010 all standing Bahá'í Houses of Worship have a dome, the Bahá'í teachings do not require that Houses of Worship have domes.[9] All Bahá'í Houses of Worship also have a prayer hall, with seats facing towards the Shrine of Baháʼu'lláh in Acre, Israel, which is the Qiblih, the direction Bahá'ís face in their obligatory prayers.[3] Bahá'í scripture also states that no pictures, statues or images may be displayed within the House of Worship and no pulpits or altars incorporated as an architectural feature (readers may stand behind a simple portable lectern).[6] Each of the Houses of Worship is unique, and to varying degrees the designs reflect the indigenous cultural, social and environmental elements of their location through the selection of materials, landscaping and architecture.[6]

Activities

Bahá'í Houses of Worship are open to all regardless of religion, gender, or any other distinction.[6] The only requirements for entry are modest dress and quiet behavior.[4] The Bahá'í laws require that only the holy scriptures of the Bahá'í Faith and other religions can be read or chanted inside in any language; while readings and prayers that have been set to music may be sung by choirs, no musical instruments may be played inside.[6] Furthermore, no sermons may be delivered, and no ritualistic ceremonies practiced.[6] Memorial services are sometimes held in Bahá'í Houses of Worship, and while wedding ceremonies are not permitted inside, they are often held in the gardens of the temples.[4] Several Bahá'í Houses of Worship have established choirs that sing music based on the Bahá'í writings (scriptures).[4] In mainly Christian countries, Bahá'í Houses of Worship offer weekly devotional services on Sundays, with the Bahá'í calendar not yet implemented for temple worship.[4]

Sociologist Margit Warburg found in her fieldwork at several Bahá'í temples that almost all attendees of weekly services were Bahá'ís but that many non-Bahá'ís visited at other times during the week.[10] Warburg has questioned whether having the temples open for visitors but without activities during most of the week is "the optimal mission strategy" for Bahá'ís, noting an account of a visitor confused by one temple's apparent lack of purpose.[5] However, researcher Graham Hassall has disputed Warburg's analysis, pointing to the large number of tourists visiting many Bahá'í Houses of Worship and positive accounts of visits in online media such as blogs.[4]

Funding and administration

Bahá'í Houses of Worship are funded by the voluntary contributions of Bahá'í communities.[6] There are no collections during temple services and only Bahá'ís are permitted to contribute to the Bahá'í funds, including funds for the construction and maintenance of Houses of Worship.[6] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi both viewed the construction of Bahá'í Houses of Worship in individual countries as projects of the international Bahá'í community.[3] Worldwide, expenses associated with Houses of Worship (and with the buildings at the Bahá'í World Centre) constitute a significant part of the spending of the Bahá'í administration.[11]

In general, a Bahá'í House of Worship and the grounds on which it is situated are the property of the Bahá'í National Spiritual Assembly of that country, and the properties are held in a financial endowment.[5] A committee of the National Spiritual Assembly of the relevant country administers the House of Worship's activities and affairs, but spiritually they see themselves as custodians of a temple that belongs to all the world's Bahá'ís.[5]

Continental Houses of Worship

The first Bahá'í House of Worship built in each (roughly) continental region is known as a "Mother temple" or continental temple; there are eight continental temples.[4][12] The plan to have a temple for each continental region was announced by Shoghi Effendi in 1953.[13]

Wilmette, U.S.

The Wilmette Bahá'í House of Worship is the oldest extant Bahá'í temple and stands on the shores of Lake Michigan near Chicago.[14] It has received architectural awards.[9] In 1978, it was added to the United States National Register of Historic Places.[9][15] In 2007, the Bahá'í House of Worship was named one of the Seven Wonders of Illinois by the Illinois Bureau of Tourism.[16][17] The temple is visited by about 250,000 people every year.[18][14]

A Chicago resident named Nettie Tobin, unable to contribute any money, famously donated a discarded piece of limestone from a construction site.[19] This stone became the symbolic cornerstone of the building.[20] During his journeys to the West, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá came to Wilmette for the groundbreaking ceremony of the temple and laid the foundation stone on 1 May 1912.[21][3] The principal architect was Louis Bourgeois,[6] though his original design ended up being amended numerous times due to impractical elements.[3] Construction began in 1921 and was completed in 1951, and the temple was dedicated in 1953.[3] The total cost of the construction was above $2.6 million.[22]

The cladding of the building is composed of a concrete mixture of Portland cement, quartz, and sand, developed for the temple by John Joseph Earley.[3] From ground level, the building stands approximately 58.2 metres tall and the diameter of the dome is 27.4 metres.[3] The auditorium seats 1,191 visitors.[6] No instrumental music is allowed during services in the auditorium, although all kinds of music may be performed in the meeting room below.[9]

Various writings of Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith, are inscribed above the building entrances and inside the interior alcoves.[23] The exterior is adorned with symbols from various religions, including the Latin Cross, the Greek Cross, the star and crescent, the Star of David, the swastika (which is an ancient symbol used in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism), and the five-pointed star.[4] Inside the center of the dome ceiling, there is a Baháʼí symbol called the "Greatest Name", consisting of Arabic script that translates as "O Thou Glory of Glories".[24] The grounds of the temple feature nine fountains, rows of Chinese junipers, and a wide range of flowers including thousands of tulips planted each fall.[18]

From 1958–2001, the Bahá'í House of Worship was associated with a "home for the aged", operated by the U.S. Bahá'í community.[8] The Bahá'í Home has since closed, although the building remains in use for a local Bahá'í School and a regional training center.[25] A new welcome centre for the House of Worship was completed in 2015, described as connecting the temple with the community, including Bahá'ís and non-Bahá'ís.[26]

Kampala, Uganda

The Kampala Baháʼí House of Worship, sometimes called the Mother Temple of Africa, is situated in the north of Kampala, Uganda's capital and largest city, on Kikaaya Hill in Kawempe Division.[27] Shoghi Effendi announced that the Kampala temple would be built in 1955 after persecution of Baháʼís in Iran made it impossible for them to build one.[28] It was designed by architect Charles Mason Remey.[4] The foundation stone was laid on 26 January 1957 by Rúhíyyih Khánum, representing Shoghi Effendi.[3] Musa Banani, the first Hand of the Cause in Africa, was also present for the groundbreaking and placed a gift of soil from the Shrine of Baháʼu'lláh, sent by Shoghi Effendi, in the foundation.[27] The dedication ceremony was held in January 1961 and was also attended by Rúhíyyih Khánum.[3]

The building is more than 39 metres high, and over 100 metres in diameter at the base.[29] The dome is over 37 metres high and 13 metres in diameter.[29] As a protection against earthquakes that can occur in the region, the temple has a foundation that goes 3 metres beneath the ground.[29] The temple has seating for 800 people.[6][3] At the time it was built, the Kampala Baháʼí temple was the tallest building in East Africa.[9]

The temple's dome is built out of fixed mosaic tiles from Italy, whereas the tiles of the lower roof are from Belgium.[4] The wall panels contain windows of green, pale blue, and amber colored glass of German origin.[4] Both the timber used for making the doors and benches and the stone used for the walls of the temple are from within Uganda itself.[4] The 50-acre (200,000 m2) property includes the House of Worship, extensive gardens, a guest house, and an administrative center.[29]

Sydney, Australia

The fourth Baháʼí temple to be completed (and third still standing) is in Ingleside in the northern suburbs of Sydney, Australia.[6] This temple serves as the "Mother Temple of the Antipodes".[4] According to Jennifer Taylor, a historian at Sydney University, it is among Sydney's four most significant religious buildings constructed in the twentieth century.[30] The initial design by Charles Mason Remey was given to Sydney architect John Brogan to develop and complete.[30] It was dedicated in September 1961 and opened to the public after four years of construction.[31]

Construction materials include crushed quartz concrete,[9] local hardwoods in the interior,[30] and concrete and marble in the dome.[31] There is seating for 600 people.[4] The building stands 38 metres in height, has a diameter at its widest point of 20 metres, and is a highly visible landmark from Sydney's northern beaches.[4] The property is set high in a natural bushland setting overlooking the Pacific Ocean.[4] The surrounding gardens contain a variety of native Australian flora including waratahs, three species of eucalypts, caleyi and other grevillea, acacia, and woody pear.[4] Other amenities located on the site include a visitors' centre, a bookshop, a picnic area, and the administrative offices of the Australian Baháʼí community.[32]

Langenhain, Germany

The Mother Temple of Europe is located at the foot of the Taunus Mountains of Germany, in the village of Langenhain near Frankfurt.[9] It was designed by German architect Teuto Rocholl.[9] The foundation stone for the temple was laid on 20 November 1960 by Amelia Collins[3] and the temple was dedicated on 4 July 1964.[9] The temple's superstructure was prefabricated in the Netherlands out of steel and concrete.[4] The center of the interior of the temple is illuminated by light shining through over 500 glass panels above.[6][4] At its base, the interior is 48 metres in diameter.[4] The height from ground level is 28.3 metres and the temple can seat up to 600 people.[3] Seena Fazel describes the House of Worship as having a "distinctive concrete and glass modernist design."[33]

Panama City, Panama

The Bahá'í temple in Panama City, Panama was designed by English architect Peter Tillotson.[6] Rúhíyyih Khánum laid the foundation stone on 8 October 1967 and temple was dedicated on 29 April 1972.[3] It is perched on a mountain named Cerro Sonsonate,[9] 10 km northeast of Panama City such that it can be seen from many parts of the city.[4] The temple is built from local stone, which is laid in designs evoking Native American fabric designs[4] and temples of the ancient Americas.[9] The dome is covered with thousands of small oval tiles[4] and rises to a height of 28 metres.[3] The temple has seats made from mahogany for up to 550 people and a floor made from terrazzo.[9]

Tiapapata, Samoa

A Bahá'í House of Worship is situated in Tiapapata, in the hills behind Apia, Samoa.[6] It was designed by Hossein Amanat.[9] Both Malietoa Tanumafili II of Samoa, the world's first Bahá'í head of state, and Rúhíyyih Khánum helped lay the foundation stone on 27 January 1979 and attended the dedication on 1 September 1984.[9] The temple was completed at a total cost of $6.5 million.[11][34] It has a 30-metre-tall domed structure[3] and seats up to 500 people in the main hall plus 200 on the mezzanine level.[4] The structure is open to the island breezes; Graham Hassall writes that this fosters a suitable environment for meditation and prayer.[4]

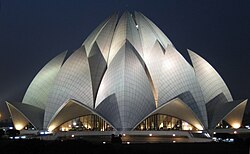

New Delhi, India

The Bahá'í House of Worship in Bahapur, New Delhi, India[4] was designed by Iranian-American architect Fariborz Sahba and is commonly known as the Lotus Temple.[35] Rúhíyyih Khánum laid the foundation stone on 17 October 1977 and dedicated the temple on 24 December 1986.[3] The total cost was $10 million.[11][34] The temple has won numerous architectural awards,[36][37] including from the Institution of Structural Engineers,[9] the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America,[9] and the Architectural Society of China.[4] It has also become a major attraction for people of various religions, with up to 100,000 visitors on some Hindu holy days;[37] estimates for the number of visitors annually range from 2.5 million to 5 million.[37][4][38]

Inspired by the sacred lotus flower, the temple's design is composed of 27 free-standing, marble-clad "petals" grouped into clusters of three and thus forming nine sides.[4] The temple's shape has symbolic and inter-religious significance because the lotus is often associated with the Hindu goddess Lakshmi.[37] Nine doors open onto a central hall[36] with permanent seating for 1,200 people, which can be expanded for a total seating capacity of 2,500 people.[6] The temple rises to a height of 40.8 metres[6] and is situated on a property that measures 105,000 square metres and features nine surrounding ponds.[36] An educational centre beside the temple was established in 2017.[38]

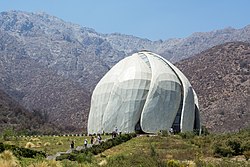

Santiago, Chile

The continental Bahá'í House of Worship for South America (or "Mother Temple for South America") is located in Santiago, Chile.[39] Shoghi Effendi announced Chile as the site for the continental temple of South America in 1953, and in 2001 the process to build the temple was launched.[13] The chosen design was by Siamak Hariri of Hariri Pontarini Architects in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.[40] Excavation was initiated at the site in 2010 and construction began in 2012.[41] The construction work was completed in October 2016,[42] with doors opening on 19 October 2016.[13] The Santiago temple cost a total of $30 million to build[13] and has won a range of Canadian and international architectural awards.[43][44][45][46][47][48]

The Santiago Bahá'í House of Worship is ringed by nine entrances, nine pathways, and nine fountains, and the structure is composed of nine arching "sails."[13] These have also been described as nine "petals" and the temple's shape as "floral"; the "petals" are separated by glass which allows light to illuminate the temple's interior.[41] The exterior of the "petals" is made from cast glass while the interior is made from Portuguese marble.[45] The sides of the temple are held up on the inside by a steel and aluminum superstructure.[13] The temple can seat 600 people[49] and it is 30 metres high and 30 metres in diameter.[41]

Local and National Houses of Worship

In the Ridván Message for 2012, the Universal House of Justice announced plans for the first local and national Bahá'í Houses of Worship to be built.[50] The first two national Houses of Worship would be in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Papua New Guinea, while the first five local Houses of Worship would be in Battambang, Cambodia; Bihar Sharif, India; Matunda Soy, Kenya; Cauca, Colombia; and Tanna, Vanuatu.[50] The Universal House of Justice characterized the Bahá'í communities chosen to host these new temples as unique in the world:

The Mashriqu'l-Adhkár [i.e., Baháʼí House of Worship], described by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá as “one of the most vital institutions of the world”, weds two essential, inseparable aspects of Bahá'í life: worship and service. The union of these two is also reflected in the coherence that exists among the community-building features of the Plan, particularly the burgeoning of a devotional spirit that finds expression in gatherings for prayer and an educational process that builds capacity for service to humanity. The correlation of worship and service is especially pronounced in those clusters around the world where Bahá'í communities have significantly grown in size and vitality, and where engagement in social action is apparent. [...] It is within these clusters that, in the coming years, the emergence of a local Mashriqu'l-Adhkár can be contemplated.[51]

Battambang, Cambodia

The Battambang, Cambodia temple was the world's first local Bahá'í House of Worship to be completed. The temple was designed by Cambodian architect Sochet Vitou Tang, who is a practicing Buddhist, and integrates distinctive Cambodian architectural principles.[52] A dedication ceremony and official opening conference took place on 1–2 September 2017, attended by Cambodian dignitaries, locals, and representatives of Bahá'í communities throughout southeast Asia.[53][54]

Agua Azul, Colombia

The temple in Agua Azul in the municipality of Villa Rica in the Cauca Department, Colombia was the second local House of Worship to be completed. The temple design, by architect Julian Gutierrez Chacon, was inspired by the shape of the cocoa pod, a plant integral to Colombian culture.[55] An opening dedication ceremony was conducted on 22 July 2018, followed by devotional services in the House of Worship.[56]

Matunda Soy, Kenya

A local Bahá'í House of Worship was opened on 23 May 2021 in Matunda Soy, Kenya.[57]

Lenakel, Vanuatu

On 13 November 2021, a local Bahá'í House of Worship opened near the town of Lenakel on the island of Tanna, Vanuatu.[58]

Others planned or under construction

Currently, construction of two national Bahá'í Houses of Worship is ongoing in Papua New Guinea[59] and the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[60] while a groundbreaking ceremony has taken place for a local Bahá'í House of Worship in Hargawan near Bihar Sharif, India.[61]

Other selected sites

As of 2010, over 120 properties had been acquired by national Bahá'í communities for the eventual construction of Bahá'í Houses of Worship.[3]

Tehran, Iran

A site was selected and purchased in 1932 for a Bahá'í House of Worship in Hadiqa, northeast of Tehran, Iran.[3] Charles Mason Remey provided a design for this temple which Shoghi Effendi then approved.[3] A drawing of the design was published in an issue of The Bahá'í World.[62] To date, however, the construction of this temple has not been possible.[3]

Haifa, Israel

A design was created for a Bahá'í House of Worship near Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel.[3] It was created by Mason Remey and approved by Shoghi Effendi in 1952.[3] A photo of the model of the Haifa House of Worship can be found in an issue of The Bahá'í World.[63] An obelisk marks the site where the House of Worship is to be built, but as of 2010, plans for the construction of this House of Worship have not been made.[3]

Eliot, Maine, U.S.

Upon his visit to Green Acre in Eliot, Maine in 1912, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stated that the second Bahá'í House of Worship in the United States would be located there.[64]

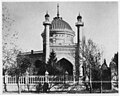

Destroyed House of Worship in Turkmenistan

The first Bahá'í House of Worship was built in the city of Ashgabat, which was then a part of Russia's Transcaspian Oblast and is now the capital of Turkmenistan.[9] It was started in 1902 and mostly completed by 1907, but was not fully finished until 1919.[65] Plans for this House of Worship were first made during the lifetime of Baháʼu'lláh.[9] The design was prepared by Ustad Ali-Akbar Banna,[9] and after his death the construction was supervised by Vakílu'd-Dawlih.[6]

The House of Worship itself was surrounded by gardens with nine ponds.[3] At the four corners of the plot of land surrounding the House of Worship were various buildings: a boys' school; a girls' school; a large meeting hall; and a group of buildings including the offices of the Local Spiritual Assembly, a reading room, and a room for meeting with enquirers.[3]

After serving the community for two decades, the House of Worship was expropriated by the Soviet authorities in 1928 and leased back to the Bahá'ís.[3] This lasted until 1938, when it was fully secularized and turned into an art gallery.[4] The 1948 Ashgabat earthquake seriously damaged the building and rendered it unsafe; the heavy rains of the following years weakened the structure, and it was demolished in 1963 and the site converted into a public park.[6]

Gallery

The first Bahá'í House of Worship (since destroyed), in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan

Baháʼí House of Worship in Langenhain, Germany

Baháʼí House of Worship in Panama City, Panama

Baháʼí House of Worship in Tiapapata, Samoa

Baháʼí House of Worship in New Delhi, India, known as the Lotus Temple

Baháʼí House of Worship in Battambang, Cambodia

Baháʼí House of Worship in Agua Azul, Colombia

Baháʼí House of Worship in Matunda Soy, Kenya

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Smith 2000, p. 235.

- ^ a b c Afnan 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Momen 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Hassall 2012b.

- ^ a b c d Warburg 2006, p. 492.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Rafati & Sahba 1988.

- ^ Warburg 2006, p. 493.

- ^ a b Warburg 2006, p. 486.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Buck 2010.

- ^ Warburg 2006, pp. 490–493.

- ^ a b c Warburg 1993.

- ^ Smith 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Razmilic 2016.

- ^ a b Stausberg 2011, p. 96.

- ^ Richardson 1997, p. 50.

- ^ Geller 2019.

- ^ Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 2007.

- ^ a b Swanson 2007.

- ^ Whitmore 1984, p. 46.

- ^ Whitmore 1984, p. 64.

- ^ Stockman 2022b.

- ^ Smith 2000, p. 236.

- ^ Whitmore 1984, p. 268.

- ^ Whitmore 1984, p. 313.

- ^ Village of Wilmette, Illinois 2004.

- ^ Routliffe 2015.

- ^ a b Zohoori 1990, pp. 134–138.

- ^ Stockman & van den Hoonaard 2022.

- ^ a b c d Rulekere 2006.

- ^ a b c Dictionary of Sydney 2008.

- ^ a b Hassall 2012a.

- ^ Badiee 2009.

- ^ Fazel 2022.

- ^ a b Smith 2000, p. 241.

- ^ Mackin-Solomon 2013.

- ^ a b c Rizor 2011.

- ^ a b c d Garlington 2006.

- ^ a b Pearson 2022.

- ^ Stockman 2022a.

- ^ Scott 2006.

- ^ a b c Díaz 2017.

- ^ Watkins 2016.

- ^ Chicago Athenaeum Museum of Architecture and Design 2017.

- ^ American Institute of Architects 2017.

- ^ a b Architecture MasterPrize n.d.

- ^ Ontario Association of Architects 2018.

- ^ Institution of Structural Engineers n.d.

- ^ Bozikovic 2019.

- ^ Royal Architectural Institute of Canada 2019.

- ^ a b Baháʼí World News Service 2012.

- ^ Universal House of Justice 2012.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2017b.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2017a.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2017c.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2018a.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2018b.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2021b.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2021c.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2019.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2022.

- ^ Baháʼí World News Service 2021a.

- ^ Baháʼí World 1963–1968, p. 495.

- ^ Baháʼí World 1950–1954, p. 548.

- ^ Atkinson 1990.

- ^ Momen 1991.

References

Books

- Afnan, Elham (2022). "Ch. 39: Devotional Life". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 479–487. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-45. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2.

- Atkinson, Anne Gordon (1990). "Introduction to Green Acre Bahá'í School". Green Acre on the Piscataqua: A Centennial Celebration. Eliot, Maine: Green Acre Baha'i School Concil.

- Fazel, Seena (2022). "Ch. 43: Europe". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 532–545. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-50. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2.

- Garlington, William (2006). "Indian Baha'i tradition". In Mittal, Sushil; Thursby, Gene R. (eds.). Religions of South Asia. London: Routledge. pp. 247–260. ISBN 0415223903.

- Hassall, Graham (2012b). "The Bahá'í House of Worship: Localisation and Universal Form". In Cusack, Carol; Norman, Alex (eds.). Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 4. Leiden: Brill. pp. 599–632. doi:10.1163/9789004226487_025. ISBN 978-90-04-22187-1. ISSN 1874-6691.

- Momen, Moojan (1991). "The Baha'i Community of Ashkhabad; its Social Basis and Importance in Baha'i History". In Akiner, Shirin (ed.). Cultural Change and Continuity in Central Asia. London: Routledge. pp. 278–305. doi:10.4324/9780203038130. ISBN 9780203038130.

- Pearson, Anne M. (2022). "Ch. 49: South Asia". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 603–613. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-56. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2.

- Smith, Peter (2022). "Ch. 41: The History of the Bábí and Bahá'í Faiths". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 501–512. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-48. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2.

- Stausberg, Michael (2011). Religion and Tourism: Crossroads, Destinations, and Encounters. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415549318.

- Stockman, Robert (2022a). "Ch. 45: Latin America and the Caribbean". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 557–568. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-52. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2.

- Stockman, Robert (2022b). "Ch. 46: North America". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 569–580. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-53. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2.

- Stockman, Robert; van den Hoonaard, Will C. (2022). "Ch. 51: Sub-Saharan Africa". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 622–636. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-58. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2.

- Warburg, Margit (2006). Citizens of the World: A History and Sociology of the Bahaʹis from a Globalisation Perspective. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14373-9.

- Whitmore, Bruce W. (1984). The Dawning Place: The Building of a Temple, the Forging of the North American Baháʼí Community. Baháʼí Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Illinois, USA. ISBN 0-87743-192-2.

- Zohoori, Elias (1990). Names and Numbers. Jamaica: Caribbean Printers Limited. ISBN 976-8012-43-9.

Encyclopedias

- Badiee, Julie (2009). "Mashriqu'l-Adhkár". Baháʼí Encyclopedia Project. Evanston, IL: National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States.

- Buck, Christopher (2010). "Temples—Baha'i Faith". In Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (eds.). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. Vol. 6. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 2817–2821. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Dictionary of Sydney staff writer (2008). "Baha'i House of Worship". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Momen, Moojan (2010). "Mašreq al-Aḏkār". Encyclopædia Iranica (online ed.).

- Rafati, V.; Sahba, F. (1988). "BAHAISM ix. Bahai temples". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. pp. 465–467.

- Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oneworld Publications, Oxford, England. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

News media

- "Plans to build new Houses of Worship announced". Baháʼí World News Service. Baháʼí International Community. 22 April 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- "Preparations for Temple inauguration accelerate". Baháʼí World News Service. 11 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Spirit and aspirations of a people: Reflections of Temple's architect". Baháʼí World News Service. 31 August 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- "Inauguration conference concludes". Bahá’í World News Service. 2 September 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- "On eve of dedication, architect reflects on culture, environment, spiritual principle". Baháʼí World News Service. 20 July 2018.

- "Colombia Temple dedicated in joyful ceremony". Baháʼí World News Service. 23 July 2018.

- "Construction advances on historic first national Baha'i House of Worship". Bahá’í World News Service. 24 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- "Ground broken for first local Bahá'í temple in India". Bahá’í World News Service. 21 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- "Kenya: First Local Bahá'í temple in Africa opens its doors". Bahá’í World News Service. 24 May 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- "Vanuatu: First local Bahá'í temple in the Pacific opens its doors". Bahá’í World News Service. 14 November 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- "DRC: Superstructure of temple nears completion". Bahá’í World News Service. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- Bozikovic, Alex (25 October 2019). "Global $100,000 prize in architecture goes to Toronto's Hariri Pontarini Architects". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Díaz, Francisco (12 January 2017). "In the Heights: The Baháʼí Temple of South America, Peñalolén, Santiago, Chile". Canadian Architect. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Mackin-Solomon, Ashley (23 January 2013). "Iranian architect living in La Jolla devoted to creating 'spiritual space'". La Jolla Light. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "'Seven Wonders' of Illinois". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 7 May 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- Routliffe, Kathy (21 April 2015). "Baha'i welcome center aims to connect neighborhood, temple". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- Rulekere, Gerald (7 September 2006). "Uganda's Bahá'í Temple". UGPulse. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- Scott, Alec (13 July 2006). "Higher Power: Toronto architect Siamak Hariri ascends to architectural greatness". CBC. Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

Other

- "AIA Innovation Award recipients selected". American Institute of Architects. 30 October 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "Baháʼí Temple of South America". Architecture MasterPrize. n.d. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Baháʼí World, vol. XII. 1950–1954.

- Baháʼí World, vol. XIV. 1963–1968.

- "The Institution of the Mashriqu'l-Adhkár". Baháʼí World. Vol. XVIII. 1979–1983.

- "International Architecture Awards 2017". The Chicago Athenaeum Museum of Architecture and Design. 18 August 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- Geller, Randall S. (2019). "The Baha'i minority in the State of Israel, 1948–1957". Middle Eastern Studies. 55 (3): 403–418. doi:10.1080/00263206.2018.1520100.

- Hassall, Graham (2012a). "The Baháʼí Faith in Australia 1947–1963". Journal of Religious History. 36 (4): 563–576. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.2012.01231.x.

- "Baháʼí Temple of South America". The Institution of Structural Engineers. n.d. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Winners of 2018 Ontario Association of Architects Awards Revealed". Ontario Association of Architects. 3 April 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Razmilic, Rayna (26 October 2016). "This Baháʼí Temple Took 14 Years To Build—It Was Worth the Wait". Metropolis. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Richardson, John (December 1997). "Preserving the Bahaʼi House of Worship: Unusual Mandate, Material, and Method" (PDF). Cultural Resource Management. National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- Rizor, John (21 August 2011). "AD Classics: Lotus Temple / Fariborz Sahba". ArchDaily. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Hariri Pontarini Architects Wins 2019 RAIC International $100,000 (CAD) Prize for Excellence in Architecture". Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. 25 October 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Swanson, Sandra (18 June 2007). "The Annotated: Baha'i Temple". Chicago. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Universal House of Justice (21 April 2012). "Riḍván 2012 - To the Baháʼís of the World". Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Village of Wilmette, Illinois (14 December 2004). "Affordable Housing Plan" (PDF). p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- Warburg, Margit (1993). "Economic Rituals: The Structure and Meaning of Donations in the Baha'i Religion". Social Compass. 40 (1): 25–31.

- Watkins, Katie (2016). "In Progress: Baháʼí Temple of South America / Hariri Pontarini Architects". archdaily.com. Arch Daily. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

Further reading

Academic publishers

- Buck, Christopher (2010). "Temples—Baha'i Faith". In Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (eds.). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. Vol. 6. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 2817–2821. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Hassall, Graham (2012). "The Bahá'í House of Worship: Localisation and Universal Form". In Cusack, Carol; Norman, Alex (eds.). Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 4. Leiden: Brill. pp. 599–632. doi:10.1163/9789004226487_025. ISBN 978-90-04-22187-1. ISSN 1874-6691.

- Momen, Moojan (2010). "Mašreq al-Aḏkār". Encyclopædia Iranica (online ed.).

- Rafati, V.; Sahba, F. (1988). "BAHAISM ix. Bahai temples". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. pp. 465–467.

Baháʼí publishers

- Armstrong-Ingram, R. Jackson (1987). Music, Devotions, and Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. Studies in Bábí and Bahá'í History. Vol. 4. Los Angeles: Kalimát Press.

- Badiee, Julie (1992). An Earthly Paradise: Baháʼí Houses of Worship Around the World. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-316-X.

- Whitmore, Bruce W. (1984). The Dawning Place: The Building of a Temple, the Forging of the North American Baháʼí Community. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-192-2.

External links

- Bahai.org: The Mashriqu'l-Adhkár

- Mashriqul-Adhkar.com - An Online Compilation (archived)

- The Bahá'í Houses of Worship around the world as seen from Google Earth

- Chronology and related documents on Bahá'í Library Online

- Related articles from the Bahá'í World News Service

- Official websites of continental Bahá'í Houses of Worship:

BoilerPlate was here

- Articles with short description

- Use dmy dates from November 2019

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2022

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Articles containing Arabic-language text

- Bahá'í House of Worship

- Religious buildings and structures in Uganda

- Religious buildings and structures in Sydney

- Religious buildings and structures in Hesse

- Religious buildings and structures in Germany

- Religious buildings and structures in Panama

- Religious buildings and structures in Samoa

- Religious buildings and structures in India

- Religious buildings and structures in Chile