Albanian Australians

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Albanians Albanian diaspora |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

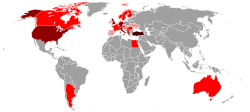

Native Albania · Kosovo Croatia · Greece · Italy · Montenegro · North Macedonia · Serbia Diaspora Australia · Bulgaria · Denmark · Egypt · Finland · Germany · Norway · Romania · South America · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom · United States |

| Culture |

| Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Dance · Dress · Literature · Music · Mythology · Politics · Religion · Symbols · Traditions · Fis |

| Religion |

|

Christianity (Catholicism · Italo-Albanian Church · Albanian Greek-Catholic Church · Orthodoxy) · Islam (Sunnism · Bektashism) · Judaism |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Albanian Gheg (Arbanasi · Upper Reka · Istrian) · Tosk (Arbëresh · Arvanitika · Cham · Lab) |

|

History of Albania (Origin of the Albanians) |

Albanian Australians (Albanian: Shqiptarë Australian) are residents of Australia who are of Albanian heritage or descent, often from Albania and North Macedonia, but also Kosovo and Montenegro with smaller numbers from Greece, Turkey, Bosnia and Italy.[2][3][4] Albanian Australians are a geographically dispersed community, with the largest concentrations in Australia being the suburb of Dandenong in Melbourne and the regional city of Shepparton, both in Victoria.[5] The Albanian community has been present in Australia for a long period of time with its presence being unproblematic and peaceful in the country.[6]

History

Early Albanian Immigration

In 1885, Naum Konxha was the first recorded Albanian to settle in Brisbane, Australia.[7][2][8] Other Orthodox Christians from southern Albania followed, Spiro Jani to Queensland (1908), Kristo Zafiri and Dhimitër Ikonomi to Townsville (1913), later came Jan Konomi (1914) and Vasil and Thomas Kasneci (1920).[9]

Interwar Period: Immigration from Albania

Arrival of young male Kurbetxhi (migrants)

After the First World War, concerns about Australia's small population's readiness to resist possible invasion and rural labour shortages made authorities accept European non-British migrants.[10][11] The first major phase of Albanian emigration to Australia began after the United States implemented quota restrictions (1924) on people from southern Europe.[2][12][13] Unable to reenter the US, from 1925 to 1926 onward, Australia became a new destination for Albanian men, a country seen as the land of economic opportunity where success could be attained.[14][15][12]

Albanian migrants came while the White Australia Policy was enforced which were a series of laws that curtailed the migration of non Anglo populations and attempted to remove people of non Anglo origin already present from the country.[16] Due to the White Australia Policy, many Muslims during the interwar period were restricted from migrating, whereas Albanians became accepted in Australia as they were considered Europeans and due to having a lighter European complexion.[17][18][12] The Australian government position was they were "required white settlers who were willing to dwell in remote and solitary surroundings and who have the experience in agricultural and pastoral pursuits, such as the Albanian possessed."[11] The Albanian arrival revived the Australian Muslim community whose aging demographics were until that time in decline[10] and Albanians became some of the earliest post-colonial Muslim groups to establish themselves in Australia.[19]

Originating from a rural background[15] Albanian migrants (Albanian: Kurbetxhi) followed a migration tradition (Kurbet), whereby sons temporarily left for another country to earn enough funds to purchase property once back in Albania.[18][13][20] In October 1924, the first 5 Albanian migrants Bejxhet Emini, Bektash Muharem, Musa Ibrahimi, Rexhep Mustafa and Riza Ali were from the Korçë region.[21][22] They[21][22] and others who followed in their footsteps embarked on a seven-week voyage and arrived at Fremantle, often becoming casual labourers mainly for the grain growing industry.[23][10][13] Over time Albanian migrants sought better employment options and relocated to rural areas of Western Australia,[24][23] Queensland and Victoria.[10][15][18] English language skills were poor or non-existent, some others were illiterate and as a result Albanian migrants had difficulties in gaining employment.[24][25] As such, Albanians arriving in the 1920s left urban centres[24] and settled in rural areas, working in the agriculture industry as horticulturalists, sugar cane workers, tobacco farmers, and market gardeners, mainly at orchards and farms.[10][14][2] Albanians were also employed in mining, scrub clearing, road works and fishing.[15]

As with other Southern European migrants, most Albanians who initially came to Australia in the 1920s were single males (between ages 15–30),[18][26][24] numbering some 1000, who worked, made money and returned to Albania to reinvest in their properties.[10][14] Women were left back in Albania, as Albanian men planned on being in Australia for a short period of time.[18] Unlike the usual two or three years Albanian migrants spent in parts of Europe or the Middle East, Australia's distance resulted in decadal stints and made return trips to Albania difficult.[13] The greatest number of Albanian arrivals occurred in 1928.[2]

Despite Albanians being considered "white", the government preferred mainly British (Christian) migrants and laws were sought to reduce the amount of visas given to southern Europeans coming to Australia.[18][27][28] The move was driven by government concerns over job competition, migrant integration within society and disruption of Australian society's Anglo-Celtic character.[24] In 1928, a quota was established making it more difficult for groups like Albanians to enter Australia unless they had 40 pounds as an insurance guarantee or a document from a sponsor.[18][28] By 1929, only 24 visas were obtained on a monthly basis by Albanians.[24] During the late 1920s and first part of the 1930s, Albanian chain migration resulted in the arrival of family and friends to Australia.[14][21] Friendship networks provided assistance to new arrivals who often originated from the same place or neighbouring villages as previous migrants from Albania.[21] Long term friendships were also made by Albanians with non-Albanians.[29] From a life of hardship in Albania, the migrants brought with them values that encompassed mutual support, respect and friendship, being ready to do work and adapt to new surroundings in Australia.[29]

The Great Depression, discrimination and wider settlement

The Great Depression (1929) impacted the majority of Albanians in Australia.[30] Rural jobs became scarce and many men, including from the Albanian community sought employment in the Western Australian goldfields.[30] By 1934, competition, disputes and riots over work at the goldfields between some Anglo-Celtic Australians and Southern Europeans like Albanians made many Albanian men move to Queensland and Victoria in the 1930s.[30] At tobacco and cotton farms in Queensland, Albanians became labourers.[21] On Queensland sugar cane farms they worked as cutters in an industry subjected to racial tests, due to British Preference Leagues wanting all workers to be of an Anglo-Celtic background.[18][21] News of difficult circumstances encountered by Albanian migrants reached the Albanian government, and as a result discounted return fares were made available to individuals undertaking the trip back to Albania.[24] Most Albanian migrants remained in Australia and sought opportunities in other parts of the country, only a minority took the government offer and returned to Albania.[24]

In the 1920s, most migrants came from southern Albania, around the city of Korçë,[31][32][13] and engaged in agriculture, especially fruit growing.[14][23] Other rural Muslim Albanians from the surrounding Bilisht area emigrated to Australia.[33] In Western Australia, early centres of Albanian settlement were Northam and York, where Albanians worked as wheat and sheep farmers, other migrants settled in Moora.[24][2][14] The first Albanian migrants in Northam were Sabri Sali and Ismail Birangi.[2] Later they, their families along with friends Fethi Haxhi and Reshit Mehmet settled in Shepparton.[2] Being seasonal labourers, some Albanians left Queensland and its sugar cane industry and others left Western Australia for Shepparton and the Yarra Valley in Victoria to work on farms.[18][34]

Establishing the Shepparton community

In Victoria, most Albanians settled on rural properties around Shepparton in the Goulburn Valley and became one of the earliest Muslim communities in the region.[2][15][35] Farm work and other agricultural employment was chosen by migrants as it required little English skills and resembled similar work they did back in Korçë.[36] For Albanian migrants, Shepparton was chosen because it reminded them of Korçë and its terrain, and prospective migrants among relatives in Albania were told it would be like home if they came.[36] The community grew through chain migration from Albania, with migrants sponsoring relatives to Australia.[37] By pooling resources together they bought businesses, established farms and some families from the community were the first to set up orchards in the region, assisting Shepparton to establish its reputation as "the fruit-bowl of Victoria".[38][34]

In the late 1930s, the Shepparton Albanian community numbered some 300–500, split between Muslims and Orthodox Christians, with some Orthodox Albanians self identifying as Greeks.[13] Tensions arose over the purchase of land in the Shepparton area by southern Europeans.[39] The local press depicted Albanians as "buying land at inflated prices, hoarding the land and distributing it among relatives and fellow countrymen" and "stealing" prime irrigated land away from locals.[40] Other depictions in the metropolitan Sydney press claimed that a quarter of Shepparton inhabitants were "aliens" and the town was becoming a "second Albania", whereas local media felt that was an exaggeration.[39] Some Albanians experienced racism from a small section of the Australian community and wider society did not consider Albanians as "white".[41]

Individually, Albanian migrants often carried large amounts of remittance cash and pistols to protect it or their properties.[42] For certain single men isolation became a problem and some violent incidents occurred between Albanians, and later decreased as families outnumbered singles.[43] Albanians nonetheless were stereotyped in the local press as prone to lawlessness and violence just for being an Albanian.[44] Most of the Shepparton population however welcomed and accepted Albanians and other migrants into the local community.[45] Albanian songs were included in concerts held by primary schools, the Country Women's Association held functions for Albanian refugees and local Shepparton inhabitants held English classes attended by some Albanians.[46] Alongside other local farmers, some Shepparton Albanian tomato growers were prominently involved in creating a union to better serve their interests in selling produce to prospective buyers.[47] In the 1930s, an Albanian migrant turned landowner Golë Feshti established an Albanian club in Shepparton.[48] As the transition of Shepparton went from town to a significant regional city, Albanians became an important part of its expanding population involved in its economic achievements and growth of the urban centre.[49]

Other settlement in Australia

Other Albanian migrants settled in Melbourne because of its manufacturing industry.[2][21] Albanian migrants became employed in manufacturing or at the Melbourne docks, others operated small businesses like shops selling fresh produce or cooked food, cafes and boarding houses.[34] In Queensland, Muslim Albanians established themselves in Mareeba and mainly Christian Albanians settled in Brisbane.[2][21] Other Albanians went to live in Cairns.[2][23][21] A smaller group of Albanians came from Gjirokastër, also speakers of the Tosk dialect group who settled primarily in urban centres such as Perth, Sydney and Melbourne, and later established small catering businesses.[2][14] Some Albanians established orchids and market gardens in Werribee.[34]

The 1933 Australian Census recorded 770 Albania-born individuals (mostly men) living in Australia, a majority based in Queensland, with smaller concentrations in Victoria (249), Western Australia, South Australia and New South Wales.[2][50][21] During this time some Albanians who had sufficient finances sponsored family members from Albania to come to Australia, including brides for single men.[51] Marriage partners were often from within the Albanian community.[51] The majority of Albanian migrants belonged to the Muslim faith, and an academic estimate placed the number of Orthodox Christians at around 40 percent.[2]

Albanian men digging irrigation trenches, Swan Hill (late 1940s)

World War Two

Internment and designation as "enemy aliens"

Until the onset of World War Two, most Albanians in Australia lacked an interest to get naturalised, as many planned on going back to Albania and reuniting with relatives.[52] The threat of a looming conflict made some Albanian migrants go to Europe to retrieve their families.[53] During the war, Italy occupied and annexed Albania[54] and the British government recognised Albania as an "autonomous" political entity.[11] In mid 1941, the designation was dropped after the declaration of war on Allied powers by the Italian controlled Albanian government, a move that adversely affected Albanians with Albanian citizenship in Australia.[11] Local rumours and reports in some rural media outlets stated the Italian consul pressured Albanians to declare as Italian citizens.[54] Members of the Albanian community expressed their concerns over the situation to authorities, the Australian government did not object to alleged actions toward Albanians, due to Albania's changed wartime status.[54] Many Albanians concerned over their status in Shepparton applied for naturalisation.[55] In Shepparton, Albanians protested an Italian community event to show loyalty to the Australian state.[56] Most Albanians in Australia rejected the imposition of Italian citizenship.[56]

The Australian government enacted the National Security Act, 1939-1940 and it outlined internment regulations.[57][58] Anyone suspected of Fascist associations or political membership were grounds for internment.[57] Some Albanians were naturalised as British subjects and the security legislation excluded them from internment regulations.[59][58] Albanians in Australia did not pose an imminent threat, by 1942, fears of an Axis invasion were high.[60] In 1942, there were 1086 Albanians in Australia and the community was designated "enemy aliens" by government authorities, due to the Italian controlled Albanian government's war declaration against the Allies.[24][61][56] Personal information was collected and the movements of people tracked.[24] Australian authorities viewed parts of the Albanian community to pose a fascist threat, with some individuals arrested and interned, others subjected to restrictions.[62][58][63] These actions were seen as essential for security.[64] The Australian government interned Albanians due to suspicions they supported Fascism or in other instances, it occurred as a result of economic rivalries, hearsay and gossip.[57][28]

Queensland had the largest concentration of Albanians in the country, and the community numbered 434 in 1941 with only 55 naturalised as British subjects.[65] In Queensland 1942, 415 Albanians were unnaturalised and only 43 were British subjects.[52] A majority of Albanian Queenslanders resided north of Ingham, numbering 224, split between Muslims and Christians.[66] Albanian Queenslanders were most affected by state actions, as anecdotal evidence pointed to some local Italians spreading anti-Allied propaganda among the community and two Albanians joining a pro-Fascist Italian group.[62][67] The Queensland government through its Security Service interned 84 Albanians and was concerned about many others that remained free.[67] In 1942, the 84 men were held in camps at Cowra in New South Wales and Enoggera in Queensland.[68] Albanians deemed "enemy aliens" and not interned were made to report to police on a regular basis and under special call-up provisions.[52] Reasons for internment varied, with some seen as a "potential danger" to society, others on political grounds because they said they were "anti-British", some were considered as suspects, and a few due to interpersonal rivalries.[69] Other instances of internment were over possessing letters in a foreign language or owing allegiance to a foreign country (Albania or Italy) and not being naturalised.[70]

Local Muslim Albanians felt they were victims of government internment policies and a small number of Catholics also experienced internment.[67] Families of interned Albanians experienced psychological trauma and humiliation.[64] Albanian men felt that they were allies of Australia, as their homeland Albania was occupied by Italy.[71] The internment created difficulties for married men with families in Albania and others who as farmers had their crops confiscated by the government.[52] Fear toward Albanians by the Australian public was related to dual identities in relation to nationality and not caused by concerns over religion.[72] Part of the wider Australian community viewed certain naturalised Albanians as posing a "potential threat".[73]

Some interned Albanians, considered by the government as physically able were placed in the Civil Alien Corps, part of the Allied Works Council, others with medical conditions came under the control of the Manpower Authorities, who oversaw what work they did.[74] Restrictions over movement were placed upon some Albanians by authorities, and a few interned individuals challenged those provisions.[75] Some Albanians protested their innocence and a National Security Regulations Department investigation showed certain Albanians were victims of personal rivalries.[75] Albanian sentiment toward the situation ranged from reluctant cooperation to acceptance and certain Albanians considered their internment conditions good, others performed poorly in tasks assigned to them by the Civil Aliens Corps.[71] Due to labour shortages in the countryside and Italy's surrender, in late 1943, the internment of Albanian Queenslanders ended and an exemption was granted from continued service in the Civil Aliens Corps.[74]

Government policies in Victoria were more lenient, with some Albanians made to report weekly to police and others involved in road construction under the direction of Manpower authorities or the Allied Works Council.[59][76] In Shepparton, as a result of Albanian employment in primary production the whole community was exempted from internment, although restrictions on travel and a firearms ban were enforced upon "enemy aliens".[56] In York, Western Australia, Albanians were the only group employed as market gardeners in the town and they received special treatment regarding internment regulations.[58] Two Albanian individuals were listed in Western Australia as interned in 1942 and because of labour demands, they claimed an exemption due to their employment as market gardeners.[58] A few other Albanians in Western Australia came under the internment system in 1943 and they were given certain forestry, labour and farming jobs to do by the Allied Works Council.[59][58]

Some Albanians not interned and without citizenship sought to resolve their position and applied for naturalisation.[59] In particular, many Albanians from Shepparton abandoned the idea of return migration and sought naturalisation as British subjects.[55] During the war, the government placed restrictions on "enemy aliens" and their naturalisation.[52] Applications took time to process as authorities investigated if applicants had broken any laws.[59] By 1943, immigration restrictions were eased for certain Albanians proven to be "pro-British" and some were naturalised.[77] In 1944, communist partisans took control of Albania from Axis German forces and Australia redesignated its Albanian community from "enemy aliens" to "friendly aliens".[56] That year, the last Albanians held in internment were freed into the community.[76]

Unlike the Germans or Italians who were considered a major wartime threat in Australia, Albanians were treated by government authorities in a fair and mainly even handed manner regarding internment and later naturalisation.[78] This was due to demand for Albanian labour, being of European stock and not posing a direct threat to the British Empire, with religion not playing a role in their wartime treatment.[78]

Albanian contribution to the Australian war effort

The Albanian community concerned that they may be viewed in Australia as having dual loyalties often made contributions to show their support for the war effort.[79] Throughout the war, Albanians financially donated to the war effort as an ethnic bloc, as the community viewed Albanian and Australian interests as one.[79] Albanians felt their contribution was one marking a transition from migrant group to a community integrated within Australia.[79] These efforts were acknowledged in Australia and admired by the press, although media representations and political stances remained unchanged toward Albanians.[79] Shepparton Albanians founded the Free Albanian Association (1943-1946), it raised money for the Red Cross and supported Albanian community integration into Australian society and their acceptance as Australians.[80] During the war, Albanians in Australia were able to maintain contact with family in Albania mainly through the Red Cross.[47]

Displays of loyalty by Albanians resulted in authorities allowing over 30 Albanian born men to enlist and serve in the Australian army during the war.[81][82][56] A majority of service men were Muslim.[56] Some Albanians served on the domestic front in combat support roles and in the Battle of Darwin.[53][56] Other Albanians were sent to the Middle East[53] and the Pacific theatre, stationed in combat divisions where they fought in places like Papua New Guinea, with a few dying oversees.[81][82][56] Some men were decorated for their war service.[56]

Postwar immigration

Influx of refugees and the Cold War

Albanians in the early decades of their migration to Australia lived a tough life based on hard work, in isolated conditions with simple living standards.[34][83] Post-war, previous economic and social difficulties, along with treatment by the government during wartime prompted some migrants to leave Australia and go back to Albania.[68][52][84] Most men remained in Australia and naturalisation became a goal to prevent any recurrence of their wartime experience in Australia.[68][52]

At the war's conclusion, the initial communist takeover of Albania was positively received by the Albanian community and later that stance changed with the onset of the Cold War.[47] Australia was preferred over Albania due to the establishment of a communist government in the country.[71] Men initially managed to get their spouses or fiancés to come from Albania.[23][68] Postwar, the establishment of an Albanian communist government implemented a policy of non-emigration and families in Albania and Australia became separated.[15][23][85] Some Albanian men with Australian citizenship went to get their families in Albania and return home to Australia, the communists however shut the borders and they became trapped and unable to leave.[85][53] A few men did manage to escape.[53] Families of migrants who tried and failed to leave were punished or subjected to hardship by the communist government, as were others with connections in the West.[53] Unmarried Albanian migrants were no longer able to bring prospective marriage partners from Albania to Australia.[53] Wartime treatment in Queensland made many Albanians leave the state for other parts of Australia.[71]

By 1947, the number of Albanian migrants had doubled from 1933, with Victoria becoming the state with the largest Albanian population in the country.[2] A gender imbalance persisted with women forming only 10 percent of the Albanian population in 1947, later increasing in 1954 to 16 percent.[14] From 1949 until 1955, 235 Albanian refugees escaping the communist takeover of Albania migrated to Australia and became part of the Shepparton community.[3][2][86] The refugees fled Albania to escape persecution, as they were supporters of the anti-communist royalist Legality Party and the Balli Kombëtar, a political party active in Albania during the war.[85][87] Other Albanian refugees from Yugoslavia came to Australia from Kosovo[88] and from southwestern Macedonia's Prespa region.[87] Albanian exiles from Prespa settled in Melbourne and Perth, and return trips to their homeland only became possible with the conclusion of the Cold War decades later.[89]

Political differences of royalists and democrats among the Albanian community existed in the immediate post war era reflecting political divisions of interwar Albania and expressed at times as separate gatherings or cultural events of the two groups.[3][39] There were tensions between some Albanians who supported the Albanian communist government and others who opposed it.[39] Over time political differences subsided.[3] Previous pro-union stances changed as the Cold War affected Albanians in rural areas.[47] They opposed joining unions, as Albanian Australians wanted to support individualism and to prevent a perceived loss of freedom like in Albania.[90] Community members felt such actions were needed so the state would accept them as loyal Australian citizens.[39]

Transition from "White Australia" to Multiculturalism

Prior to the 1960s, the majority of the Albanian population in Australia was born in Albania.[47] As a result of the Albanian refugee influx, the Australia wide Albanian born population increased and peaked to its highest numbers until 1976.[2] Postwar till the 1990s, the political environment in Albania interrupted and affected marriage customs among Albanian Australians like finding Albanian spouses or organising Albanian weddings.[91] Some Albanian Australians resorted to marrying people from Albanian populated areas in Yugoslavia and Turkey.[91][92] Other Albanians in Australia married Muslims from different Muslim communities or non-Muslim spouses.[91]

Postwar Albanian migration, as with other Muslim immigrant communities occurred during the transition from the White Australia Policy to a Multicultural Policy.[93] The arrival of post war migrants of non-Anglo-Celtic origin made Australia shift over the years from the policy of White Australia to Multiculturalism.[94] Intended to deal with population influx, Multiculturalism permitted people to hold on to their particular culture and address difficulties migrants encountered in Australia regarding resources and services.[94]

In the Australian context of notions about race and ethnicity, the settlement of (Muslim) Albanians during the White Australia policy period made them straddle various classifications of White due to skin colour, and also considered as the "Other".[95] Islam was not an impediment for Albanians arriving to Australia and undergoing the naturalisation process.[96] Mosques were built by Albanians during the White Australia era.[97] Later with the implementation of official Multiculturalism, the term Ethnic is used to describe groups like (Muslim) Albanians as being "non Anglo" or the "Other" in discourses about the policy by the majority Anglo-Australian population.[98] Some in the Albanian community see their light-coloured skin and European heritage as factors that allowed them to integrate.[99] Australian Albanians like their Anglo-Celtic counterparts are at times deemed "invisible ethnics" and mobile within the spectrum of "Whiteness" with Albanians as a result being accepted in Australia at certain points in Australian history.[100] In Australian scholarship, various reasons are given for the allowance of Albanians and their gradual acceptance in Anglo-Celtic Australia while still considered somewhat different or as "ethnics".[101] They range from the Albanian presence being tolerated due to their small numbers, compatibility with the White Australia policy by having a light European complexion, filling labour shortages or not being of Asian origin.[101]

Postwar Shepparton and Melbourne communities

The Australian census of 1947 recorded 227 Shepparton Muslims, most from an Albanian background.[102] In local media negativity toward postwar Shepparton Albanians decreased sharply and they were depicted as a hard working people with civic participation in the town.[46] In the early 1950s, Shepparton Albanians established their own Albanian Muslim Society and it fundraised among their community, building Victoria's first mosque toward the end of the decade.[103][104][2] Albanians partook in the revival of Islamic life within Australia during the 1950s, in particular toward creating networks and institutions for the community.[105] Religious and social survival prompted Albanians, like other Muslims of different ethnic backgrounds who were geographically dispersed to cooperate with each other on social projects through Muslim associations.[106]

The Islamic Society of Victoria (ISV) was established (late 1950s), its first head was an Albanian and during the early 1960s Albanians formed the majority of its membership.[107] The multicultural organisation laid foundations for Muslim groups like the Albanians to individually create Muslim facilities and infrastructure over time for their growing community.[108] Albanians based in Melbourne established their own Albanian Muslim Society and constructed the city's first mosque in the late 1960s.[109][104] A multicultural Muslim women's association was established in North Carlton during the late 1960s and Albanian women were some of its members.[110] Albanian radio was established in Melbourne by Bahri Begu and Luk Çuni.[111] In 1974, an Albanian Catholic Society was established and in 1993, an Australian Albanian Women's Association was created.[112][113][114]

During the 1990s, migration programmes were set up in the Goulburn Valley to aid with Albanian family reunifications and the sponsoring of migrants.[85][115] An estimated 100 Albanian families migrated to Shepparton after the collapse of communism in Albania.[15][86][115] Coming from the same region in Albania, they joined the older Shepparton Albanian community who as family contacts[116] sponsored their work visas, gave them support through their social networks and often employment.[86][15][14] Some of the new Albanian arrivals were able to gain Australian citizenship through descent from earlier migrant forebearers with Australian citizenship who were unable to leave Albania following the Second World War.[86][117][115] Shepparton Albanians became a well integrated and financially successful community, with many employed as market gardeners and orchardists.[24][118][119]

The Albanian presence in Shepparton is "well known and well regarded".[120] Some history books about Shepparton document the important Albanian contribution to its growth and development.[121] They include accounts of tomato farmer Sam Dhosi, landowner Golë Feshti, orchardist Sam Sali or Ridvan (Riddy) Ahmet and his brother who founded a trucking business transporting fresh produce to Melbourne and dominating the market in the present.[122] Notable figures from the local Albanian community have been honoured in Shepparton for their achievements with streets named after them.[121] These are Feshti Street for Golë Feshti, Asim Drive for Ismet Asim, a young Albanian migrant who later owned orchards and a dairy farm, and others such as Sabri Drive, Sam Crescent and Sali Drive.[122]

Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, New South Wales & Northern Territory

In Queensland, Albanians purchased land in the tobacco growing areas of Mareeba and others in the corn growing region of the Atherton Tablelands.[123] In Mareeba, the older community was joined by post-war Albanian refugees,[31][124] and other Albanians settled down in Brisbane or areas where sugar cane was grown like Cairns and Babinda.[125][126] From the 1940s till 1960s, some Albanians moved to live and work in forest and farms areas of Kenilworth, Caboolture, Jimna, Beerwah and Glasshouse Mountains.[127] Apart from individual Albanians, work on the tobacco and sugarcane farms often involved the whole family.[126] Albanians brought their experience of work in a rural environment and applied it by contributing significantly to the state's farming sector.[126]

The new Albanian arrivals in Mareeba sought to preserve traditions suppressed under communism in their former homeland.[128] As such, the wider Mareeba Albanian community established their own local Muslim Society organisation, and built a mosque dedicated to Australian soldiers who lost their lives in war.[129][128][79] A few Albanians in Brisbane partook in establishing a multicultural Muslim organisation, the Islamic Society of Queensland in the late 1950s.[130]

From their arrival, the Albanian Mareeba community has maintained good relations with the local Anglo-Celtic Australian population, even during the Second World War, as both groups share a similar rural lifestyle and interests.[131] In 1976, adult Muslims with an Albanian origin numbered 98 in Mareeba.[66] A few local Albanians have risen to leadership roles such as becoming directors of the North Queensland Tobacco Growers' Co-operative Association, that fought for tobacco growers' interests.[132] Young people among the community have preferred employment in urban centres.[132]

Among Albanian communities within Australia, reverence is maintained for its financial contribution to the World War Two effort and its Australian war veterans.[79] Albanians through their community organisations have partaken in annual ANZAC Day commemorations at the war memorial.[79]

Some postwar Muslim migrants from Albania went to live in Western Australia, in particular to Fremantle and in Perth settling nearby the old city mosque alongside other Muslims.[133] In Perth, Albanians were involved in establishing the Muslim Society of Australia in the late 1940s.[134] Other postwar Muslim Albanian migrants went to live in Northam and York, the state's wheat and sheep farming regions, and gained employment as gardeners or farmers.[133] In South Australia, the postwar Albanian community became interconnected with other multi-ethnic Muslim migrants through Islamic community societies.[105] The state had 150 Albania-born people and some 300 of Albanian descent in 1993.[7] By the 1990s, small numbers of Albanians had settled in Darwin, Northern Territory.[135] In New South Wales, some early postwar migrants were a small number of Albanians who settled in Sydney.[136] Others in the state went to live in Wollongong and over 200 people are of Albanian descent.[137][138]

Immigration from southwestern Yugoslavia

The majority of Albanian-speaking arrivals in the country migrated from the former Yugoslavia, beginning in the 1950s.[2][139] From the 1960s-1970s the majority of these migrants were from the Lake Prespa region and the villages of Kišava and Ostrec of Bitola municipality, all located in modern south-western North Macedonia (then part of Yugoslavia).[4][139] Many left Yugoslavia due to discrimination as an ethnic Albanian minority and Muslim population, and the deteriorating economy and rise in unemployment.[140]

Settlement in Dandenong

In 1963, Jakup Rustemi and later the brothers Tahir and Vefki Rasimi became the first Albanians to settle in Dandenong after migrating from Kišava.[141][142] Chain migration by Albanians from Kišava later assisted and brought other friends and family to Australia.[141] Migrating Albanians mainly had agricultural skills and they chose Dandenong as a destination for settlement because it had industry and farms located on the suburban outskirts.[142] An Albanian soccer club was founded by local Albanians in 1984.[142] A mosque was built by the Dandenong Albanian community[143] in 1985.[142] As the Dandenong Albanian community became settled and grew, they lacked a voice and representation and their interests were not a focus of local and state government until the mid-2000s.[144]

Dandenong over time became a centre for arriving Albanian migrants from southern Yugoslavia, and the suburb attracted some Albanian migrants from other parts of Australia who wanted to be in an Albanian environment.[145] Albanians also live in the neighbouring small suburb of Dandenong South, and comprise much of its population.[146] Albanians form much of the kindergarten and school populations in the Dandenong area.[147] Two story houses are a common feature among many Albanian homeowners in Dandenong, and often they make up most of the population in certain streets were they are concentrated.[148][142] Many Albanian households are extended or multigenerational families that contribute toward preserving traditions and the Albanian language.[142] Some features of Albanian life in Dandenong are the speaking of Albanian, the sounds of Balkan music heard in the area, Albanian cuisine and local Albanian businesses.[144]

Albanians in Dandenong consider themselves as integrated and accepted in Australia.[149] Dandenong Albanians are employed in various occupations.[150] Some are involved in the flower cultivation industry working in nearby flower farms.[150] Dandenong Albanians own over 40 flower and vegetable farms on Dandenong's suburban outskirts and some 100 businesses in Dandenong itself.[142] Many women also are in employed in various occupations, although a sizable number are housewives focusing on child rearing.[150] Following the opening of borders by post communist Albania in 1991, there was a rise in marriages by Dandenong Albanians mainly with origins from Macedonia to Albanians from Albania.[151] The Albanian presence has been honoured in Dandenong with a street called Keshava Grove and the creation of a public park in 2020 named Keshava Reserve.[142]

Other settlement in Melbourne

As these migrants are from the same Tosk dialect group, they were able to integrate with earlier immigrants from the Korçë area.[4] This was due to shared historical, social and cultural connections and intermarriage that allowed the forming of strong bonds of community in Australia.[4] The Albanian Prespa community and those Albanians from the Bitola region form the majority of the Albanian community in Victoria and Australia.[3][4] In 1991, they numbered 5,401.[4][152]

Industrial working class suburbs in Melbourne are the main areas of Albanian settlement with Bitola Albanians mainly in Dandenong and Prespa Albanians in Yarraville, St Albans, Altona, Preston, Lalor and Thomastown.[2][4][152] Within the context of migration, maintaining identity and adapting to a new homeland, Albanians from the lake Prespa region refer to Australia as Australia shqiptare (Albanian Australia) or Australia prespane (Prespan Australia).[153] As a consequence of the Albanian migratory outflow from the region, the Prespa diaspora communities in Australia and the US are larger than the Albanian Prespa population left in Macedonia.[154]

The 1990s, Kosovo War and aftermath

In the 1996 census, Albanians were mainly employed in the agriculture, services and production industries, as labourers, tradespeople and smaller numbers as professionals, with less than a quarter being unemployed.[2] The Albanian language was spoken by 6212 people in 1996, a fivefold increase over people born in Albania.[2] Of that number, some 1299 were born in the Republic of Macedonia and 60 in Serbia and Montenegro.[2]

The Albanian community has mostly kept a low profile in Australia, only coming to national attention during the disintegration of Yugoslavia and the resulting Kosovo crisis of the 1990s.[2][155] During the Kosovo War (1999), the Australian government conducted Operation Safe Haven and gave temporary asylum to 4000 Kosovo Albanians by housing them in military facilities, although Albanian Australians offered to house the refugees.[2][156][152] The event shaped a pivotal change in Australian government policy toward refugees by offering temporary asylum instead of permanent settlement.[157] In Victoria, 1,250 Kosovo Albanians were housed at two army bases, Puckapunyal in the Shepparton area and Portsea, located south from Dandenong.[158] Local Albanians from both areas provided the refugees with support and assisted them with interpreting and translation.[158] Some Albanian community organisations and networks in Australia were involved in giving assistance to Kosovo Albanian refugees.[157][159][115] Erik Lloga, a local Melbourne based Albanian community leader led efforts and was the main interlocutor between the Australian government and refugees.[159][157][160]

Post war, most Albanian refugees were returned to Kosovo in 2000 and 500 were able to remain after attaining refugee status and permanently remaining in Australia, increasing the numbers of Albanian Australian community.[161][162][115] It was the last main phase of immigration to Australia by Albanians.[152] Albanian Australians in areas where they are concentrated and their organisations assisted the Kosovars with resettlement.[115] Small numbers of Kosovo and Montenegro born Albanians settled in Mareeba, where Albanian Australians form most of its Muslim population.[163][31][164] In Queensland, Kosovo Albanians form one third of its Albanian population and are employed as carpenters and painters or involved in other labour trades, with the youth pursuing other professions in law, health or engineering.[165]

Twenty first century

In the early twenty first century, a majority of Albanians in Australia live in Victoria.[8] At Shepparton, the Albanian community numbers some 3,000 and the overwhelming majority have origins from Korçë or its neighbouring countryside in Albania.[166] In Dandenong, the Albanian community numbers between 4,000 and 6,000, most originating from Kišava and its surrounding area in North Macedonia.[167] In both places, some Albanians have origins from Montenegro and Kosovo, and in Dandenong some have origins from Albania.[3][150] Most Albanians in Shepparton and Dandenong are Muslims.[168]

Australia wide, the 2006 Australian census counted 2,014 Albanians born in Australia[169] with 11,315 having Albanian ancestry.[170] In 2011, the census counted 2,398 Albanians born in Australia[1] and 13,142 with Albanian ancestry.[1] The 2016 census counted 4,041 people born in Albania or Kosovo and 15,901 with Albanian ancestry.[1]

Some Albanian Australians have found it difficult to sponsor Albanians for migration from the Balkans to Australia, as they did not have the required English language skills.[171] Australian immigration rules tightened in the contemporary period and marriage has become the main option for migration to Australia by Albanians from the Balkans.[172] Some Albanian Australians have married Albanians from the Balkans.[91] The end of communism in Albania and the breakup of Yugoslavia restarted the tradition of some second and third generation Albanian Australians marrying Albanians from places they originated from in the Balkans.[91] Limited numbers of Albanian migrants have also arrived through Australian humanitarian, refugee and skilled migration programmes.[115]

In Victoria, Albanian Australians have risen to political leadership roles such as Jim Memeti, serving as City of Greater Dandenong mayor,[173] Dinny Adem and Shane Sali as mayors for the City of Greater Shepparton.[174][175][176] In late 2007 to early 2008, an exhibition named "Kurbet" (migration) on the Albanian migration experience to Australia was displayed at the Immigration Museum in Melbourne.[177][178] Shepparton Albanians for some years through their Islamic Society association devoted efforts toward having the towns of Shepparton and Korçë establish a twin-town relationship, a goal achieved in 2013.[179] During December 2019, Albanian Australians, through their community organisations raised $255,000 for 2019 Albania earthquake victims.[180]

In the early 2020s, the COVID-19 pandemic spread in Australia and in Victoria, its impacts were felt by Victorian Albanians with community events like Albanian festivals being cancelled.[181][182] During August 2020 in Dandenong, some 100 individuals mostly from the Albanian community partook in the first anti-lockdown protests against Victoria's lockdowns that aimed at curbing the COVID-19 pandemic.[183] In late 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic severely affected the Albanian community in Melbourne with some 300 people becoming infected with the virus.[184]

The Shepparton Albanian community produced Australia My Home: An Albanian Migration, a documentary about Albanian migration to Australia.[185][186] In 2022 it has been shown in film festivals in Australia, the US, Albania and won awards.[185][186]

Demographics

In the early twenty first century, Victoria has the highest concentration of Albanians and smaller Albanian communities exist in Western Australia, South Australia, Queensland, New South Wales and the Northern Territory.[187][188] In 2016, approximately 4,041 persons resident in Australia identified themselves as having been born in Albania and Kosovo, while 15,901 persons identified themselves as having Albanian ancestry, either alone or in combination with another ancestry.[1] According to Australian Albanian societies, they state the number of Albanians in the country is under reported.[86]

Language

Albanian of the Tosk and Gheg dialects is used by Albanian Australians.

In Shepparton, Albanian language usage had declined among a large number of Albanian Australians to the point that it was barely used or no longer spoken.[189] An influx of Albanian migrants from Albania to Shepparton in the 1990s led to a revival of Albanian among the older group of Shepparton Albanians who wanted to reconnect with their heritage through the Albanian language.[189]

In the late twentieth century, proficiency in the Albanian language among Albanian Australians ranged from infancy to the elderly, being maintained by the second generation and spoken by more recent migrant arrivals of the time.[2] From 1986 till 1996, usage of the Albanian language increased by a quarter, and some older migrants were not fluent in English.[2]

In the early twenty first century, Albanian Australians from the second and third generations mainly speak English as their primary language.[190] Among the young they can understand Albanian, but have a reluctance to use it and instead prefer to speak English.[191] Some Albanian households are heavily involved in efforts toward the transmission and maintenance of the Albanian language by their children in Australia.[192][126]

Albanian migrants in the twentieth century established Sunday schools for learning Albanian.[193] The first Albanian school was established by Bahri Begu and Luk Çuni.[194] Its inaugural Albanian language class was held in 1964 and taught by its first teacher Mithat Jusufi, an Albanian from Bitola who immigrated in 1961.[195] In Victoria, continued support for maintaining the Albanian language has come from the education system through the Victorian School of Languages (VSL) and community schools teaching languages.[196] Albanian language classes undertaken through the VSL system are held on the weekends in Shepparton and the Melbourne suburbs of Brunswick, Dandenong and Caroline Springs.[197][198]

Religion

Islam

In the late twentieth century, 80% of Albanian speakers in Australia followed Islam.[2] As Islam is the dominant religion among Albanian Australians, it has given the community a sense of unity and the capacity and resources to construct their own mosques.[2][199][200] They have symbolised the Albanian community's permanent settlement in Australia.[201] Mosques serve as important centres for community activities and are pivotal toward retaining the religious identity of Albanian Australians.[68]

The Shepparton Mosque was the first mosque built in Victoria,[18][68] and the Carlton Mosque was the first mosque built in Melbourne.[2] Other mosques in metropolitan Melbourne are the Dandenong Mosque[202] and the Albanian Prespa Mosque in Reservoir.[203][204] The mosque built in Mareeba[2] was the second in Queensland and the first in its rural interior. In Western Australia, Perth based Albanians use the old city mosque.[133] Albanian representatives serve in most federal Islamic organisations, with some in senior positions.[205][86] In the few areas of concentrated Albanian settlement, their small numbers shaped local areas through the construction of their first mosques or becoming a sizable proportion of the school Muslim population.[122] The foundations created by Albanian Australians have attracted future Muslim migrants to areas which have an existing mosque or services assisting with settlement.[122]

From the interwar period until the 1950s Albanian identity was closely associated with being Muslim in Albanian communities like Shepparton.[206] These were significant elements that contributed to their place in the country and established sentiments of community among its members.[206] In the modern period, Albanians in Australia such as in Shepparton and Dandenong are secular or non-observant Muslims, with some devout in Islam.[207] The Albanian perception of their community is that they are integrated in Australia, tolerant Muslims with relaxed religious practices and a "laid back" outlook on religion.[208] Albanians hold that a lack of religious knowledge does not diminish one's own Muslim identity.[209]

A small number of Albanian women, mainly older individuals, wear Muslim head coverings and the practice is considered acceptable by Albanian Australians.[209] Among some Albanians, the month long Ramadan fast is lightly adhered to with the effort seen as important and not the completion of its fasting requirements.[210] Albanians perform certain traditions like an Albanian imam sacrificing a sheep prior to the construction of a house for good luck, something considered non-Islamic by other imams and in Islam.[211] At Shepparton, practice of Islam by the present local Albanian community is influenced by the legacy of Sufi Bektashism from Albania.[212]

In the Albanian community, there has been some trepidation toward and difficulty in relating to newly arrived Middle Eastern Muslims whose practice of Islam is often devout and visible.[213] Sharing a European background has made Albanians be more open to the British origins of a large part of the Australian population.[99] A lack of commonality and turbulent Balkan legacy have distanced Albanians from efforts by some non-Albanian Muslim bodies to supersede ethnic and national organisations for a unitary Muslim only approach advocating for community interests.[214] Albanians in Australia keep a low profile, due to a legacy of discrimination and persecution experienced in the Balkans under communism, as minorities or from war.[214]

Among Albanians, people identify as "Albanian" or "Australian", and the two identities are often not easily distinguished by community members, unless they are recent migrants.[215] Both identities are viewed as not being too dissimilar from each other by the Albanian community.[215] Some segments of the Australian Muslim population regard Albanians as "white Muslims".[41] In places where Albanians are concentrated like Shepparton, the broader non-Muslim population view them as tolerant Muslims.[216]

Differing views exist among the Albanian community over Islam.[217] Older generations belonging to the pre-1950s migration flow view their connection to Islam as intact and "authentic", and consider the Islam of recent arrivals who lived under communist imposed atheism as severed from their past and sense of self.[218] A sizable number of Albanian migrants from post communist Albania identify as Muslim, but are not keen on openly associating themselves with Islam due to being in Australia.[219] Among newer Albanian migrants post 1991 and some older community members or individuals raised in Australia, they view older members of the Albanian community who were cut off from Albania for decades as holding on to past practices that no longer exist in the Balkan country.[220] Amid some of the young generations and newer Albanian arrivals, they view the stances of older generations linking Albania and Islam as a concern and incompatible with the current situation in Australia.[221] For them, they are not closely attached to Islam or see it connected to their nationality and view expressions of an Islamic heritage as a negative in Australia, due to problematic media coverage of Muslims.[221] There are Albanians who do not view being Muslim as a barrier to integration within the mainly Christian population of Australia.[99] Some Albanians view Christianity as the "true" faith of the Albanian people, whereas others see Muslim and Albanian identity as intertwined.[222]

Christianity

Christian Albanian Australians numbered 400 Catholics and 114 Orthodox in the late twentieth century.[2] Catholic and Orthodox Albanian Australians, following their migration and settlement, use existing religious institutions in Australia for their religious needs.[223][224] Christian Albanian Australians have difficulties in preserving their heritage, due to a lack of Albanian-speaking clergy and Albanian churches in Australia.[223] In April 2022, the Catholic Albanian community erected a statue of Saint Mother Teresa in Adelaide.[225]

Community and Culture

Albanian Australians of Muslim and Christian backgrounds are united by a shared heritage and common Albanian identity.[223] Religious differences have not been a significant factor in Albanian community relations.[3] In Australia, social networks and relations in the context of a common language, family, migration and cultural practices play a significant role in influencing being Muslim, an Albanian and belonging to a community.[226]

Among Albanian communities in Victoria certain geographic or political designations have been carried over from the Balkan countries of origin they arrived from to identify or differentiate each other.[227] Places like Shepparton are identified with Albanians from the Korçë area in Albania, and Dandenong with Albanians from the Bitola area in North Macedonia.[228] Other identity references exist toward northerners and southerners, Albanians from pre or post communist Albania, Kosovar Albanians, cultural or linguistic differences, religion, or Albanians settled in other parts of Australia like Mareeba.[229] Overall, with some exceptions in Dandenong, these complex social and identity markers among Albanian Victorians are not source of contention.[230] Similarities are also highlighted between Albanian communities and there is acceptance of differences along with the notion that people self identifying as Albanians form one cohesive group.[231] People in attendance at large social gatherings like community festivals or new year's parties, are all identified as Albanian by Albanian Australians.[232] As the geopolitical situation has changed over time in both the Balkans and Australia, it has become increasingly difficult to identify differences among Albanians from their specific country of origin like Albania, Macedonia, Kosovo or Montenegro.[233] Often many identify Albania as "home" when referring to an individual's heritage or regarding the nation of origin, even if they had arrived from Montenegro or Macedonia.[233] Connections to certain villages and urban centres in the Balkans from which Albanian Australians came from are maintained and its reflected in the social links people and families have with one another in Australia which are based on those places.[179][154]

There are efforts among Albanians to maintain certain cultural traditions.[126] Albanian cultural mediums such as Albanian T.V. programmes, music and local recordings of Albanian social events like large Albanian weddings are present in households.[192] Other traditions continue such as the cultural concept of Besa.[83]

Community organisations, associations and sports clubs

Albanian Australians have established various community organisations, religious associations and sports clubs to cater for the needs of their geographically dispersed community.[2][193] In Carlton North, Melbourne there is the Albania Australia Community Association (AACA) and Albanian Australian Islamic Society, both share the same premises.[157] Other Albanian Islamic societies exist in Dandenong and in Shepparton.[2] An Albanian Catholic Society is based in St Albans.[157][112][234] There is an Albanian Teachers' Association,[157] the Australian Albanian Women's Association,[113][235][114] the Australian Albanian Prespa Association,[204] the Australian Albanian Pensioners Association,[236][237] and the United Albanians of Australia Association.[238] The Albanian Folk Dance Group is based in Melbourne.[239] A branch of the Balli Kombëtar political party was present in Victoria, being established by post-war refugees with anti-communist sentiments.[157]

Throughout Melbourne, Albanian Australians founded some of its soccer clubs.[193] Dandenong Thunder is based in Dandenong[240] and North Sunshine Eagles are in St. Albans.[241][242] Other teams are the Heidelberg Eagles and South Dandenong.[241]

An Albanian Association of Brisbane exists in Queensland and in the rural interior, the Albanian Australian Moslem Society of Mareeba.[157][243] In Adelaide, South Australia there is an Albanian Australian Association,[157] the Mother Teresa Albanian Catholic Society and Adelaide Albanian Folk Dance Group.[244][225]

Cultural dates, gatherings, functions and weddings

Albanians belonging to various generations, religions, affiliations and origins gather and associate freely at community cultural events celebrating Albanian culture and Albania.[3][248][126] Albanians in Australia celebrate Albanian Independence day (28 November),[3][193][126] host and attend community New Year's celebrations and Albanian music concerts, and partake in other functions.[248] Celebrations marking the conclusion of Ramadan are also a focal point for the community.[193]

In Shepparton, such events are organised by the local Albanian Islamic Society who also holds the annual Albanian Harvest Festival at the Shepparton showgrounds and attended by some 2000 people, mainly Albanian Australians.[249] In Dandenong, the Albanian-Australian Community Association organises community events and its annual Albanian festival is held in the Dandenong Ranges.[250][3][251] The festival date falls every first Sunday in December and at times it also has been held in Melbourne's inner western suburbs.[251][252][253] At both festivals, Albanian music and dance are a feature and Albanian culture is celebrated, the events attract Albanians from other areas in Victoria to Shepparton or Dandenong and are important in connecting the dispersed Albanian community, families and friends.[3][254][251]

The Albanian community sometimes participate in multicultural events like the Shepparton Festival in Shepparton and the Piers Festival in Dandenong.[255] Albanian culture including its music, dance and national costume is celebrated and showcased along with the contribution of Albanian folkloric performers.[255]

Various events hosted by Albanian soccer clubs are important for socialisation among Albanians and others from the broader community.[193] The club grounds of Dandenong Thunder in Dandenong are utilised by the Albanian-Australian Community Association for a majority of community events they organise including Albanian music concerts hosting Albanian performers from the Balkans.[256] The club grounds also hosts the Qamil Rexhepi Cup, played annually in January[142] between local Albanian Melbourne based soccer clubs. In Dandenong, the coffee shop and gym are often places were Albanian men socialise and women do so at other women's houses, the shopping centre, the local park and swimming pool.[257]

In Queensland, Albanians socialise at picnics, barbecues, in community dinners where traditional drinks and communal singing are a feature and celebrate Albanian Independence day where Albanian folkloric music and dances are practised.[165]

Festivals and other celebrations showcasing Albanian culture, music and food are events that serve as reminders or links for Albanian Australians of their Albanian identity or ancestral past.[258] They are also places where social networks are strengthened and recognised in the context of friendship and support.[259]

Weddings are important events among the Albanian community.[91] Often they are big celebrations, mainly lavish and full of symbolism.[91] Marriages signify and mark an important transition and position in the social status of a new couple, their parents and grandparents within the Albanian community.[91]

Food

Albanian cuisine is consumed in Australia. Some dishes are Lakror, a pastry with fillings such as cheese and spinach, tomato, onion and pepper, fried doughballs called Petulla, Revani, a semolina and sherbet cake and Bakllava, a sweet multilayered pastry filled with nuts.[260] Efforts are devoted by some households to pass on culinary Albanian traditions to younger generations.[192]

Musical traditions

Various musical genres and dances exist among Albanians in Australia reflecting the regions within the Balkans from where they migrated and stylistic differences exist that typify traditional music from northern and southern Balkan Albanian areas.[3] Polyphonic singing, associated with southern Albanian musical traditions refer to a singer beginning a song followed by a second singer entering at a different melodic line with others maintaining a drone (iso) is mainly performed by elderly Prespa Albanians of both genders, though separately, at weddings.[3]

Northern Albanian musical traditions of solo singing are performed by Albanians from Kosovo. The repertoire of songs often involve love songs and narrative ballads about historic or legendary events played on a stringed musical instrument like the çifteli or lahutë.[3] There also exist a variety of local Albanian music bands composed of a vocalist and often accompanied by other members playing a clarinet, drums, electric guitar and piano accordion, increasingly substituted for an electric keyboard.[261] These bands perform at weddings or other gatherings and their music repertoire often reflects the influences from their place of origin in the Balkans, with some creating new musical compositions in Australia.[261]

Bands who reflect a Kosovo Albanian origin often sing about patriotic or political themes alongside traditional songs and their music contains Turkish influences dating from the Ottoman era.[3] Traditional dances are performed with some of the most popular being the Shota for Kosovo Albanians, the Ulqin for Montenegro Albanians and the Devollice for Southern Albanians.[3] Some dances previously performed by only one gender are increasingly being danced together by both males and females and many younger members of the Albanian community partake in traditional dancing.[3]

Notable people

Community leaders

- Memet Zuka – community leader and a founder of the Albanian Australian Islamic Society[262]

- John P. Duro – community leader and founder of the Albanian Association of Queensland[126]

- Jeanette Mustafa – community leader and a founder of the Australian Albanian Women's Association[263][264][265]

- Erik Lloga – community leader, Australian-Albanian National Council chairman, interpreter[157][266]

Humanities, medicine and sciences

- Zihni Buzo – civil engineer

- Avni Sali – professor, surgeon, clinician and researcher

- Perparim Xhaferi – academic at RMIT University and Melbourne University[267][268]

Business

- Remzi Mulla – tobacco farmer, chairman of the Queensland Tobacco Board[126]

- Zimi Meka – mining engineer, founder of the multinational energy and resources company Ausenco[126]

Politics and law

- Jim Memeti – City of Greater Dandenong mayor

- Dinny Adem – City of Greater Shepparton mayor

- Shane Sali – current City of Greater Shepparton mayor

- Rauf Soulio – District Court judge in South Australia[269]

Religion

- Rexhep Idrizi – imam[270]

- Benjamin Murat – imam[271][272][273]

- Bekim Hasani – imam, scholar and current head of sharia affairs at the Islamic Coordinating Council of Victoria (ICCV)[274][275][276]

Film, music, theatre, arts and entertainment

- Alex Buzo – playwright and author

- Arta Mucaj – actress

- Agim Hushi – tenor

- Adem Kerimofski – musician

Sports

- Ibrahim Balla – boxer, participant in the London Olympic Games and Delhi Commonwealth Games representing Australia

- Qamil Balla – boxer, participant in the Delhi Commonwealth Games representing Australia

- Besart Berisha – football (soccer) player, Melbourne Victory

- Ellvana Curo – football (soccer) player, Box Hill United and Albania

- Labinot Haliti – football (soccer) player, Newcastle Jets

- Mehmet Duraković – former football (soccer) player, South Melbourne FC and Australia; football coach

- Susie Ramadan – WBC World bantamweight Champion. The first Australian woman to win a professional world boxing title

- Taip Ramadani – Handball player, head coach of the Australian men's national handball team

- Adem Yze – Australian rules footballer, has made the third highest number of appearances in the history of the Melbourne Football Club

See also

- Albanian New Zealanders

- Albanian diaspora

- Albanians in North Macedonia

- Albanians

- Albania–Australia relations

- Australia–Kosovo relations

- European Australians

- Europeans in Oceania

- Immigration to Australia

References

- ^ a b c d e f "TableBuilder".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Jupp 2001, p. 166.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Scott-Maxwell 2003, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f g "After World War II". Immigration Museum. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 42, 44, 55, 263.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 263–265.

- ^ a b Migration Museum (1995). From Many Places: The History and Cultural Traditions of South Australian People. Wakefield Press. pp. 22, 24. ISBN 9781862543478.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, p. 34.

- ^ Duro, John P. (1981). Emigracioni i Shqipetareve ne Australi. Brisbane. pp. 1–20.

- ^ a b c d e f Aslan, Alice (2009). Islamophobia in Australia. Agora Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9780646521824.

- ^ a b c d Kabir 2004, p. 130.

- ^ a b c Amath 2017, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e f Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1172.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barjaba, Kosta; King, Russell (2005). "Introducing and theorising Albanian migration". In King, Russell; Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (eds.). The new Albanian migration. Brighton: Sussex Academic. p. 8. ISBN 9781903900789.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carswell, Sue (2005). "From Albania and Turkey to Shepparton: The experiences of migrants in regional Victoria". Around the Globe. 2 (2): 28–29.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 130–131, 186.

- ^ Pratt, Douglas (2011). "Antipodean Ummah: Islam and Muslims in Australia and New Zealand". Religion Compass. 5 (12): 744. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2011.00322.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cleland, Bilal (2001). "The History of Muslims in Australia". In Akbarzadeh, Shahram; Saeed, Abdullah (eds.). Muslim communities in Australia. UNSW Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780868405803.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 186.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ahmeti 2017, p. 35.

- ^ a b "A foreign land". Immigration Museum. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Carne 1984, p. 185.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Amath 2017, p. 99.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1171.

- ^ Sullivan, Mary Lucille (1993). "The Years of Decline: Australian Muslims 1900-40". In Sullivan, Mary Lucille; Kazi, Abdul Khaliq (eds.). An Australian Pilgrimage: Muslims in Australia from the Seventeenth Century to the Present. Victoria Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780724184507.

- ^ Amath 2017, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b c Ahmeti 2017, p. 162.

- ^ a b "Friendships and mutual support". Immigration Museum. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Kabir 2005, p. 561.

- ^ a b c Volz, Martin (2009). "Tropical tapestry - North Queensland is home to a diverse range of communities of people who choose to live amid the forests and fruit". Big Issue Australia (342): 19.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 44, 233.

- ^ Vullnetari, Julie (September 2007). "Albanian Migration and Development: State of the art review". IMISCOE (International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion). p. 17. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Gur mbi gur bën mur – 'stone on stone makes a wall'". Immigration Museum. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1169, 1172.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 44, 47, 201, 232.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 35, 43, 44, 47, 186–187, 231–232.

- ^ a b c d e Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1180.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1174, 1180, 1182.

- ^ a b Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1181.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1175.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1174–1175.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1175, 1183.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1181–1182.

- ^ a b Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1182.

- ^ a b c d e Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1179.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 46, 187.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 186–187

- ^ Kabir 2005, p. 560.

- ^ a b Kabir 2005, pp. 560–561.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kabir 2004, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Going 'home'". Immigration Museum. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1176.

- ^ a b Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1176–1177.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1177.

- ^ a b c Kabir 2004, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e f Kabir, Nahid (2005). "Muslims in Western Australia 1870-1970". Early Days: Journal of the Royal Western Australian Historical Society. 12 (5): 562.

- ^ a b c d e Kabir 2006, p. 201.

- ^ Amath 2017, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Kabir 2004, pp. 125, 130.

- ^ a b Kabir 2006, p. 200.

- ^ Kabir 2004, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Kabir 2004, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Kabir 2004, pp. 130–132.

- ^ a b Carne 1984, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Kabir 2004, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d e f Amath, Nora (2017). "We're serving the community, in whichever form it may be": Muslim Community Building in Australia". In Peucker, Mario; Ceylan, Rauf (eds.). Muslim Community Organizations in the West: History, Developments and Future Perspectives. Springer. p. 100. ISBN 9783658138899.

- ^ Kabir 2004, p. 136.

- ^ Kabir 2004, pp. 134, 136.

- ^ a b c d Carne 1984, p. 188.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1174–1176.

- ^ Kabir 2004, p. 133.

- ^ a b Kabir 2004, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b Kabir 2004, p. 134.

- ^ a b Kabir 2004, p. 137.

- ^ Kabir 2004, p. 139.

- ^ a b Kabir 2004, pp. 137–140.

- ^ a b c d e f g Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1178.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1178–1179.

- ^ a b Kabir, Nahid (2006). "Muslims in a 'White Australia': Colour or Religion?". Immigrants & Minorities. 24 (2): 201–202. doi:10.1080/02619280600863671. S2CID 144587003.

- ^ a b Kabir, Nahid Afrose (2004). Muslims in Australia: Immigration, Race Relations and Cultural History. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781136214998.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, p. 204.

- ^ Carne 1984, pp. 185–188.

- ^ a b c d Ahmeti 2017, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f Barry & Yilmaz 2019, p. 1173.

- ^ a b Domachowska, Agata (2019). "Albania". In Mazurkiewicz, Anna (ed.). East Central European migrations during the Cold War: A handbook. De Gruyter. p. 15. ISBN 9783110607536.

- ^ Haveric 2019, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Pettifer, James; Vickers, Miranda (2021). Lakes and Empires in Macedonian History: Contesting the Waters. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 125. ISBN 9781350226142.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1179–1180.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Weddings". Immigration Museum. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Aliu 2004, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 242.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, p. 152.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 54, 152, 162, 186.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 159.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 87.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 152, 155, 162, 186, 263, 265.

- ^ a b c Ahmeti 2017, p. 154.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 152, 162, 265.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Barry & Yilmaz 2019, pp. 1172–1173.

- ^ Haveric 2019, pp. 80–81, 85.

- ^ a b Saeed, Abdullah; Prentice, Patricia (2020). Living in Australia: A Guide for Muslims New to Australia (PDF). National Centre for Contemporary Islamic Studies - University of Melbourne. p. 11.

- ^ a b Haveric 2019, p. 27.

- ^ Haveric 2019, pp. 28, 84.

- ^ Haveric 2019, pp. 83–84, 95.

- ^ Haveric 2019, pp. 83, 101.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 86.

- ^ Haveric 2019, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Aliu 2004, p. 46

- ^ a b Kajtazi, Sani (17 March 2018). "Lek Ndreka from Albanian Catholic Society of Melbourne". SBS. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b SBS Albanian (17 September 2017). "25th Anniversary of the Australian Albanian Women's Association". SBS. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ a b SBS Albanian (21 November 2014). "Shoqata e Grave Australiane Shqiptare" [Albanian Australian Women's Association] (in Albanian). SBS. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Recent arrivals". Immigration Museum. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 44.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 46.

- ^ Renaldi, Erwin (19 November 2019). "Masjid Pertama di Melbourne Dibangun Oleh Pendatang Asal Albania" [Melbourne's First Mosque Was Built By Albanian Migrants] (in Indonesian). ABC. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 46, 47.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, pp. 187, 232–233.

- ^ a b c d Ahmeti 2017, p. 187.

- ^ Carne 1984, p. 186.

- ^ Davis, Sam (28 April 2010). "Keeping the faith". Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ Haveric 2019, pp. 144, 153.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Braho, Hakki (2015). "Albanians" (PDF). We are Queenslanders: Contemporary multicultural tapestry of people. Ethnic Communities Council of Queensland. p. 12.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 144.

- ^ a b Carne 1984, pp. 191–193.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 154.

- ^ Haveric 2019, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Carne 1984, pp. 188–190.

- ^ a b Carne, J.C. (1984). "Moslem Albanians in North Queensland" (PDF). In Dalton, B. J. (ed.). Lectures on North Queensland history. University of North Queensland. p. 189. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Haveric 2019, p. 159.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 160.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 199.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 126.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 139.

- ^ Wollongong City Council. "Ancestry". Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, p. 37.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 37, 60.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, pp. 55, 232.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rexhepi, Nizami (31 August 2021). "Historia e vendosjes së 4 mijë shqiptarëve në qytetin Dandenong" [The history of the settlement of 4 thousand Albanians in the city of Dandenong] (in Albanian). Diaspora Shqiptare. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 39, 56, 106.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, p. 213.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 56.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 56, 187–188.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 58, 153.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d Ahmeti 2017, p. 232.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 233, 256.

- ^ a b c d Ahmeti 2017, p. 38.

- ^ Pistrick, Eckehard (2015). Performing nostalgia: Migration culture and creativity in south Albania. Ashgate Publishing. p. 106. ISBN 9781472449535.

- ^ a b Aliu 2004, p. 44

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 38, 45, 213.

- ^ Carr 2011, pp. 23, 98.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jupp, James (2001). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, its People and their Origins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780521807890.

- ^ a b Ahmeti 2017, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Taylor, Savitri (2000). "Protection or Prevention? A Close Look at the New Temporary Safe Haven Visa Class" (PDF). University of New South Wales Law Journal. 23 (3): 80.

- ^ Carr, Robert A. (2011). The Kosovar refugees: The experience of providing temporary safe haven in Australia (Ph.D.). University of Wollongong. pp. 161, 172–173, 175, 185, 192, 199, 200–201, 212, 219, 237. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Jupp 2001, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 39.

- ^ Haveric 2019, p. 153.

- ^ Braho 2015, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Braho 2015, p. 13.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 42, 44, 202, 232–233, 260, 263, 267.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 41–42, 55–56, 202, 213, 232, 260, 263, 267.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 41, 263.

- ^ "20680-Country of Birth of Person (full classification list) by Sex - Australia" (Microsoft Excel download). 2006 census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2 June 2008. Total count of persons: 19,855,288.

- ^ "20680-Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex - Australia" (Microsoft Excel download). 2006 census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2 June 2008. Total responses: 25,451,383 for total count of persons: 19,855,288.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, p. 132.

- ^ Ahmeti 2017, pp. 201–202.

- ^ "Quiet achievers honoured at Greater Dandenong Australia Day ceremony". Greater Dandenong Leader. 31 January 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2019.