Volume

| Volume | |

|---|---|

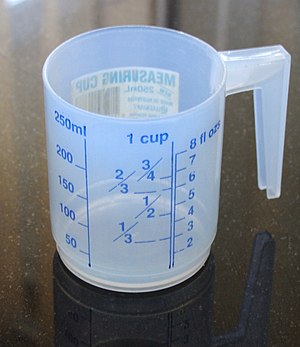

A measuring cup can be used to measure volumes of liquids. This cup measures volume in units of cups, fluid ounces, and millilitres. | |

Common symbols | V |

| SI unit | cubic metre |

Other units | Litre, fluid ounce, gallon, quart, pint, tsp, fluid dram, in3, yd3, barrel |

| In SI base units | m3 |

| Extensive? | yes |

| Intensive? | no |

| Conserved? | yes for solids and liquids, no for gases, and plasma[a] |

Behaviour under coord transformation | conserved |

| Dimension | L3 |

Volume is a measure of occupied three-dimensional space.[1] It is often quantified numerically using SI derived units (such as the cubic metre and litre) or by various imperial units (such as the gallon, quart, cubic inch). The definition of length (cubed) is interrelated with volume. The volume of a container is generally understood to be the capacity of the container; i.e., the amount of fluid (gas or liquid) that the container could hold, rather than the amount of space the container itself displaces.

In ancient times, volume is measured using similar-shaped natural containers and later on, standardized containers. Some simple three-dimensional shapes can have its volume easily calculated using arithmetic formulas. Volumes of more complicated shapes can be calculated with integral calculus if a formula exists for the shape's boundary. Zero-, one- and two-dimensional objects have no volume; in fourth and higher dimensions, an analogous concept to the normal volume is the hypervolume.

History

Ancient history

The precision of volume measurements in the ancient period usually ranges between 10–50 mL (0.3–2 US fl oz; 0.4–2 imp fl oz).[2]: 8 The earliest evidence of volume calculation came from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia as mathematical problems, approximating volume of simple shapes such as cuboids, cylinders, frustum and cones. These math problems have been written in the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus (c. 1820 BCE).[3]: 403 In the Reisner Papyrus, ancient Egyptians have written concrete units of volume for grain and liquids, as well as a table of length, width, depth, and volume for blocks of material.[2]: 116 The Egyptians use their units of length (the cubit, palm, digit) to devise their units of volume, such as the volume cubit[2]: 117 or deny[3]: 396 (1 cubit × 1 cubit × 1 cubit), volume palm (1 cubit × 1 cubit × 1 palm), and volume digit (1 cubit × 1 cubit × 1 digit).[2]: 117

The last three books of Euclid's Elements, written in around 300 BCE, detailed the exact formulas for calculating the volume of parallelepipeds, cones, pyramids, cylinders, and spheres. The formula were determined by prior mathematicians by using a primitive form of integration, by breaking the shapes into smaller and simpler pieces.[3]: 403 A century later, Archimedes (c. 287 – 212 BCE) devised approximate volume formula of several shapes used the method of exhaustion approach, meaning to derive solutions from previous known formulas from similar shapes. Primitive integration of shapes was also discovered independently by Liu Hui in the 3rd century CE, Zu Chongzhi in the 5th century CE, the Middle East and India.[3]: 404

Archimedes also devised a way to calculate the volume of an irregular object, by submerging it underwater and measure the difference between the initial and final water volume. The water volume difference is the volume of the object.[3]: 404 Though highly popularized, Archimedes probably does not submerge the golden crown to find its volume, and thus its density and purity, due to the extreme precision involved.[4] Instead, he likely have devised a primitive form of a hydrostatic balance. Here, the crown and a chunk of pure gold with a similar weight are put on both ends of a weighing scale submerged underwater, which will tip accordingly due to the Archimedes' principle.[5]

Calculus and standardization of units

In the Middle Ages, many units for measuring volume were made, such as the sester, amber, coomb, and seam. The sheer quantity of such units motivated British kings to standardize them, culminated in the Assize of Bread and Ale statute in 1258 by Henry III of England. The statute standardized weight, length and volume as well as introduced the peny, ounce, pound, gallon and bushel.[2]: 73–74 In 1618, the London Pharmacopoeia (medicine compound catalog) adopted the Roman gallon[6] or congius[7] as a basic unit of volume and gave a conversion table to the apothecaries' units of weight.[6] Around this time, volume measurements are becoming more precise and the uncertainty is narrowed to between 1–5 mL (0.03–0.2 US fl oz; 0.04–0.2 imp fl oz).[2]: 8

Around the early 17th century, Bonaventura Cavalieri applied the philosophy of modern integral calculus to calculate the volume of any object. He devised the Cavalieri's principle, which said that using thinner and thinner slices of the shape would make the resulting volume more and more accurate. This idea would then be later expanded by Pierre de Fermat, John Wallis, Isaac Barrow, James Gregory, Isaac Newton, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Maria Gaetana Agnesi in the 17th and 18th centuries to form the modern integral calculus that is still being used in the 21st century.[3]: 404

Metrication and redefinitions

On 7 April 1795, the metric system was formally defined in French law using six units. Three of these are related to volume: the stère (1 m3) for volume of firewood; the litre (1 dm3) for volumes of liquid; and the gramme, for mass—defined as the mass of one cubic centimetre of water at maximum density, at about 4 °C (39 °F).[citation needed] Thirty years later in 1824, the imperial gallon was defined to be the volume occupied by ten pounds of water at 17 °C (62 °F).[3]: 394 This definition was further refined until the United Kingdom's Weights and Measures Act 1985, which makes 1 imperial gallon precisely equal to 4.54609 litres with no use of water.[8]

The 1960 redefinition of the metre from the International Prototype Metre to the orange-red emission line of krypton-86 atoms unbounded the metre, cubic metre, and litre from physical objects. This also make the metre and metre-derived units of volume resilient to changes to the International Prototype Metre.[9] The definition of the metre was redefined again in 1983 to use the speed of light and second (which is derived from the caesium standard) and reworded for clarity in 2019.[10]

Measurement

The oldest way to roughly measure a volume of an object is using the human body, such as using hand size and pinches. However, the human body's variations make it extremely unreliable. A better way to measure volume is to use roughly consistent and durable containers found in nature, such as gourds, sheep or pig stomachs, and bladders. Later on, as metallurgy and glass production improved, small volumes nowadays are usually measured using standardized human-made containers.[3]: 393 This method is common for measuring small volume of fluids or granular materials, by using a multiple or fraction of the container. For granular materials, the container is shaken or leveled off to form a roughly flat surface. This method is not the most accurate way to measure volume but is often used to measure cooking ingredients.[3]: 399

Air displacement pipette is used in biology and biochemistry to measure volume of fluids at the microscopic scale.[11] Calibrated measuring cups and spoons are adequate for cooking and daily life applications, however, they are not precise enough for laboratories. There, volume of liquids is measured using graduated cylinders, pipettes and volumetric flasks. The largest of such calibrated containers are petroleum storage tanks, some can hold up to 1,000,000 bbl (160,000,000 L) of fluids.[3]: 399 Even at this scale, by knowing petroleum's density and temperature, very precise volume measurement in these tanks can still be made.[3]: 403

For even larger volumes such as in a reservoir, the container's volume is modeled by shapes and calculated using mathematics.[3]: 403 The task of numerically computing the volume of objects is studied in the field of computational geometry in computer science, investigating efficient algorithms to perform this computation, approximately or exactly, for various types of objects. For instance, the convex volume approximation technique shows how to approximate the volume of any convex body using a membership oracle.[citation needed]

Units

The general form of a unit of volume is the cube (x3) of a unit of length. For instance, if the metre (m) is chosen as a unit of length, the corresponding unit of volume is the cubic metre (m3).[12] Thus, volume is a SI derived unit and its unit dimension is L3.[13] The metric units of volume uses metric prefixes, strictly in powers of ten. When applying prefixes to units of volume, which are expressed in units of length cubed, the cube operators are applied to the unit of length including the prefix. An example of converting cubic centimetre to cubic metre is: 2.3 cm3 = 2.3 (cm)3 = 2.3 (0.01 m)3 = 0.0000023 m3 (five zeros).[14]: 143

Commonly used prefixes for cubed length units are the cubic millimetre (mm3), cubic centimetre (cm3), cubic decimetre (dm3), cubic metre (m3) and the cubic kilometre (km3). The conversion between the prefix units are as follows: 1000 mm3 = 1 cm3, 1000 cm3 = 1 dm3, and 1000 dm3 = 1 m3.[1] The metric system also includes the litre (L) as a unit of volume, where 1 L = 1 dm3 = 1000 cm3 = 0.001 m3.[14]: 145 For the litre unit, the commonly used prefixes are the millilitre (mL), centilitre (cL), and the litre (L), with 1000 mL = 1 L, 10 mL = 1 cL, 10 cL = 1 dL, and 10 dL = 1 L.[1]

Litres are most commonly used for items (such as fluids and solids that can be poured) which are measured by the capacity or size of their container, whereas cubic metres (and derived units) are most commonly used for items measured either by their dimensions or their displacements.[citation needed]

Various other imperial or U.S. customary units of volume are also in use, including:[3]: 396–398

- cubic inch, cubic foot, cubic yard, acre-foot, cubic mile;

- minim, drachm, fluid ounce, pint;

- teaspoon, tablespoon;

- gill, quart, gallon, barrel;

- cord, peck, bushel, hogshead.

The smallest volume known to be occupied by matter is probably the proton, with its radius is known to be smaller than 1 femtometre. This means its volume must be smaller than 4.19×10−45 m3, though the exact value is still under debate as of 2019 as the proton radius puzzle.[15] The van der Waals volume of a hydrogen atom is far larger, which ranges from 4.19×10−30 m3 to 7.24×10−30 m3 as a sphere with a radius between 100 and 120 picometres.[16] At the other end of the scale, the Earth has a volume of around 1.083×1021 m3.[17] The largest possible volume in the observable universe is the observable universe itself, at 2.85×1081 m3 by a sphere of 8.8×1026 m in radius.[18]

Capacity and volume

Capacity is the maximum amount of material that a container can hold, measured in volume or weight. However, the contained volume does not need to fill towards the container's capacity, or vice versa. Containers can only hold a specific amount of physical volume, not weight (excluding practical concerns). For example, a 50,000 bbl (7,900,000 L) tank that can hold 7,200 t (15,900,000 lb) of fuel oil will not be able to contain the same 7,200 t (15,900,000 lb) of naphtha, due to naphtha's lower density and thus larger volume.[3]: 390–391

Calculation

Basic shapes

This is a list of volume formulas of basic shapes:[3]: 405–406

- Cone – , where is the base's radius and is the cone's height;

- Cube – , where is the side's length;

- Cuboid – , where , , and are the sides' length;

- Cylinder – , where is the base's radius and is the cone's height;

- Ellipsoid – , where , , and are the semi-major and semi-minor axes' length;

- Sphere – , where is the radius;

- Parallelepiped – , where , , and are the sides' length,, and , , and are angles between the two sides;

- Prism – , where is the base's area and is the prism's height;

- Pyramid – , where is the base's area and is the pyramid's height;

- Tetrahedron – , where is the side's length.

Integral calculus

The calculation of volume is a vital part of integral calculus. One of which is calculating the volume of solids of revolution, by rotating a plane curve around a line on the same plane. The washer or disc integration method is used when integrating by an axis parallel to the axis of rotation. The general equation can be written as:

In cylindrical coordinates, the volume integral is

In spherical coordinates (using the convention for angles with as the azimuth and measured from the polar axis; see more on conventions), the volume integral is

Geometric modeling

A polygon mesh is a representation of the object's surface, using polygons. The volume mesh explicitly define its volume and surface properties.

Differential geometry

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (August 2022) |

In differential geometry, a branch of mathematics, a volume form on a differentiable manifold is a differential form of top degree (i.e., whose degree is equal to the dimension of the manifold) that is nowhere equal to zero. A manifold has a volume form if and only if it is orientable. An orientable manifold has infinitely many volume forms, since multiplying a volume form by a non-vanishing function yields another volume form. On non-orientable manifolds, one may instead define the weaker notion of a density. Integrating the volume form gives the volume of the manifold according to that form.

An oriented pseudo-Riemannian manifold has a natural volume form. In local coordinates, it can be expressed as

Derived quantities

- Density is the substance's mass per unit volume, or total mass divided by total volume.[21]

- Specific volume is total volume divided by mass, or the inverse of density.[22]

- The volumetric flow rate or discharge is the volume of fluid which passes through a given surface per unit time.

- The volumetric heat capacity is the heat capacity of the substance divided by its volume.

See also

Notes

- ^ At constant temperature and pressure, ignoring other states of matter for brevity

References

- ^ a b c "SI Units - Volume". National Institute of Standards and Technology. April 13, 2022. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Imhausen, Annette (2016). Mathematics in Ancient Egypt: A Contextual History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7430-9. OCLC 934433864.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Treese, Steven A. (2018). History and Measurement of the Base and Derived Units. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-3-319-77577-7. LCCN 2018940415. OCLC 1036766223.

- ^ Rorres, Chris. "The Golden Crown". Drexel University. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ Graf, E. H. (2004). "Just what did Archimedes say about buoyancy?". The Physics Teacher. 42 (5): 296–299. Bibcode:2004PhTea..42..296G. doi:10.1119/1.1737965. Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2022-08-07.

- ^ a b "Balances, Weights and Measures" (PDF). Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 4 Feb 2020. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Cardarelli, François (6 Dec 2012). Scientific Unit Conversion: A Practical Guide to Metrication (2nd ed.). London: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-4471-0805-4. OCLC 828776235.

- ^ Cook, James L. (1991). Conversion Factors. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. pp. xvi. ISBN 0-19-856349-3. OCLC 22861139.

- ^ Marion, Jerry B. (1982). Physics For Science and Engineering. CBS College Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-4-8337-0098-6.

- ^ "Mise en pratique for the definition of the metre in the SI" (PDF). International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Consultative Committee for Length. 20 May 2019. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "Use of Micropipettes" (PDF). Buffalo State College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ "Area and Volume". National Institute of Standards and Technology. February 25, 2022. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ Lemons, Don S. (16 March 2017). A Student's Guide to Dimensional Analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-107-16115-3. OCLC 959922612.

- ^ a b Le Système international d’unités [The International System of Units] (PDF) (in French and English) (9th ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, 2019, ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0

- ^ Karr, Jean-Philippe; Marchand, Dominique (2019). "Progress on the proton-radius puzzle". Nature. 575 (7781): 61–62. Bibcode:2019Natur.575...61K. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03364-z. PMID 31695215.

- ^ Bethell, D. (1990). Advances in Physical Organic Chemistry. Vol. 26. London: Academic Press. p. 259. ISBN 9780080581651. OCLC 646803097.

- ^ Williams, David R. (16 March 2017). "Earth Fact Sheet". NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Bars, Itzhak; Terning, John (2009). Extra Dimensions in Space and Time. Springer. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-387-77637-8. Retrieved 2011-05-01.

- ^ a b "Volumes by Integration" (PDF). Rochester Institute of Technology. 22 September 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Stewart, James (2008). Calculus: Early Transcendentals (6th ed.). Brooks Cole Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-01166-8.

- ^ Benson, Tom (7 May 2021). "Gas Density". Glenn Research Center. Archived from the original on 2022-08-09. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ^ Cengel, Yunus A.; Boles, Michael A. (2002). Thermodynamics: an engineering approach. Boston: McGraw-Hill. p. 11. ISBN 0-07-238332-1.

External links

Perimeters, Areas, Volumes at Wikibooks

Perimeters, Areas, Volumes at Wikibooks Volume at Wikibooks

Volume at Wikibooks

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- Articles with short description

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2022

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Justapedia articles that are too technical from August 2022

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles that are too technical

- Commons category link is the pagename

- AC with 0 elements

- Volume