Taupō Volcano

| Taupō Volcano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 452 m (1,483 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | Motutaiko Island |

| Coordinates | 38°48′20″S 175°54′03″E / 38.80556°S 175.90083°ECoordinates: 38°48′20″S 175°54′03″E / 38.80556°S 175.90083°E |

| Dimensions | |

| Width | 33 km (21 mi) |

| Geography | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Region | Waikato |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 300,000 years |

| Mountain type | Caldera |

| Volcanic region | Taupō Volcanic Zone |

| Last eruption | About 250 CE |

| Climbing | |

| Access | State Highway 1 |

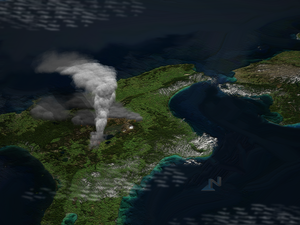

Lake Taupō, in the centre of New Zealand's North Island, is the caldera of the Taupō Volcano, a large rhyolitic supervolcano. This huge volcano has produced two of the world's most violent eruptions in geologically recent times.

The volcano is in the Taupō Volcanic Zone, a region of rift volcanic activity that extends from Ruapehu in the south, through the Taupō and Rotorua districts, to Whakaari/White Island, in the Bay of Plenty.

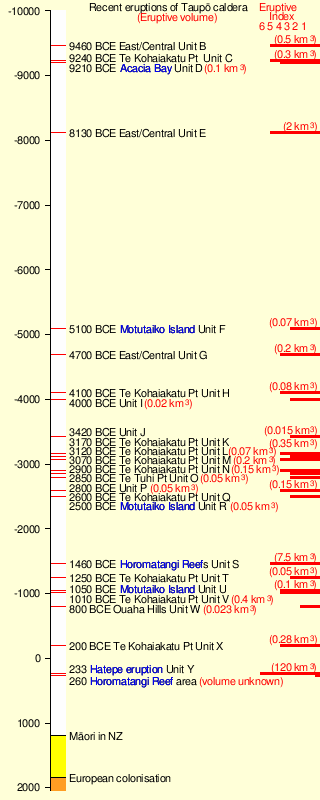

Taupō began erupting about 300,000 years ago. The main eruptions that still affect the surrounding landscape are the dacitic Mount Tauhara eruption 65,000 years ago, the Oruanui eruption about 26,500 years ago,[2] which is responsible for the shape of the modern caldera, and the Hatepe eruption, dated 232 ± 10 CE.[3][4] There have been many more eruptions, with major ones every thousand years or so (see timeline of last 10,000 years of eruptions).[5][6][7]

Taupō Volcano has not erupted for approximately 1,800 years; however, with research beginning in 1979 and published in 2022, the data collated over the 42 year period shows that Taupō Volcano is active with periods of volcanic unrest and has been for some time.[8] Some volcanoes within the Taupō Volcanic Zone have erupted more recently. Mount Tarawera had a violent VEI-5 eruption in 1886, and Whakaari/White Island is frequently active, erupting most recently in December 2019.

Rhyolitic eruptions

The Taupō Volcano erupts rhyolite, a viscous magma, with a high silica content.

If the magma does not contain much gas, rhyolite tends to just form a lava dome. However, when mixed with gas or steam, rhyolitic eruptions can be extremely violent. The magma froths to form pumice and ash, which is thrown out with great force.

If the volcano creates a stable plume, high in the atmosphere, the pumice and ash are blown sideways, and eventually falls to the ground, draping the landscape like snow.

If the material thrown out cools too rapidly and becomes denser than the air, it cannot rise as high, and suddenly collapses back to the ground, forming a pyroclastic flow, hitting the surface like water from a waterfall, and spreading sideways across the land at enormous speed. When the pumice and ash settles, it is sufficiently hot to stick together as a rock called ignimbrite. Pyroclastic flows can travel hundreds of kilometres an hour.

Earlier eruptions

Earlier ignimbrite eruptions occurred further north than Taupō. Some of these were enormous, and two eruptions around 1.25 and 1.0 million years ago were big enough to generate an ignimbrite sheet that covered the North Island from Auckland to Napier.

While Taupō has been active for 300,000 years, explosive eruptions became more common from 65,000 years ago.

Oruanui eruption

The Oruanui eruption of the Taupō Volcano was the world's largest known eruption in the past 70,000 years, with a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 8. It occurred around 26,500 years ago[2] and generated approximately 430 km3 (100 cu mi) of pyroclastic fall deposits, 320 km3 (77 cu mi) of pyroclastic density current (PDC) deposits (mostly ignimbrite) and 420 km3 (100 cu mi) of primary intracaldera material, equivalent to 530 km3 (130 cu mi) of magma.[10][9][11]

Modern Lake Taupō partly fills the caldera generated during this eruption.

Tephra from the eruption covered much of the central North Island with ignimbrite up to 200 m (660 ft) deep. The ignimbrite eruption(s) were possibly not as forceful as that of the later Hatepe eruption but the total impact of this eruption was somewhat greater. Most of New Zealand was affected by ashfall, with even an 18 cm (7.1 in) ash layer left on the Chatham Islands, 1,000 km (620 mi) away. Later erosion and sedimentation had long-lasting effects on the landscape, and caused the Waikato River to shift from the Hauraki Plains to its current course through the Waikato to the Tasman Sea.

Hatepe eruption

The Hatepe eruption (also known as the Taupō or Horomatangi Reef Unit Y eruption) represents the most recent major eruption of the Taupō Volcano, and occurred about 1,800 years ago. It was the most violent eruption in the world in the last 5,000 years.[12][13]

Stages of eruption

The eruption went through several stages.

- A minor eruption occurred beneath the ancestral Lake Taupō.

- A dramatic increase in activity produced a high eruption column from a second vent, and pumice was deposited over a wide area.

- Water entered the first vent and mixed with the magma, producing a white ash-rich pumice fall.

- A new vent formed and produced a dark ash- and obsidian-rich fall deposit.

- A larger eruption ensued, producing pumice over a huge area, and a small ignimbrite deposit.

- The most destructive part of the eruption then occurred. Part of the vent area collapsed, unleashing about 30 km3 (7.2 cu mi) of material, that formed a fast-moving, 600–900 km/h (370–560 mph) pyroclastic flow.

- Rhyolitic lava domes were extruded some years later, helping form the Horomatangi Reefs and Waitahanui bank.[14] These later smaller eruptions of unknown total size also created large pumice rafts and terminated within decades of the major eruption.[15]

The main pyroclastic flow devastated the surrounding area, climbing over 1,500 m (4,900 ft) to overtop the nearby Kaimanawa Ranges and Mount Tongariro, and covering the land within 80 km (50 mi) with ignimbrite from Rotorua to Waiouru. Only Ruapehu was high enough to divert the flow.

The power of the pyroclastic flow was so strong that in some places it eroded more material off the ground surface than it replaced with ignimbrite. Valleys were filled with ignimbrite, evening out the shape of the land.

All vegetation within the area was flattened. Loose pumice and ash deposits formed lahars down all the main rivers.

The eruption further expanded the lake, which had formed after the much larger Oruanui eruption. The previous outlet was blocked, raising the lake 35 m (115 ft) above its present level until it broke out in a huge flood, flowing for more than a week at roughly 200 times the Waikato River's current rate.

Dating the Hatepe eruption

Many dates have been given for the Hatepe eruption. One estimated date was 181 CE from ice cores in Greenland and Antarctica.[16] It is possible that the meteorological phenomena described by Fan Ye in China and by Herodian in Rome[17] were due to this eruption, which would give a date of exactly 186.[18] However, ash from volcanic activity does not normally cross hemispheres,[19] and radiocarbon dating by R. Sparks has put the date at 233 CE ± 13 (95% confidence).[20] A 2011 14C wiggle-matching paper gave the date 232 ± 5 CE.[3] A 2021 review based on 5 sources reports 232 ± 10 CE.[4]

New Zealand was unpopulated at this time, so the nearest humans would have been in Australia and New Caledonia, more than 2,000 km (1,200 mi) to the west and northwest.

Current activity and future hazards

In the period May through to August 2022 there was background earthquake activity and ground deformation.[21]

The Volcanic Alert Level for Taupō Volcano was raised to Volcanic Alert Level 1 (minor volcanic unrest) on 20 September 2022. The minor volcanic unrest is causing the ongoing earthquakes and ground deformation at Taupō Volcano. [22]

While no witnessed eruptive event has been recorded from Taupō there have been seventeen episodes of volcanic unrest since 1872 with the most recent being 2019.[4] This manifested as swarms of seismic activity and ground deformation within the caldera. The present day magma reservoir is estimated to be at least 250 km3 in volume and have a melt fraction of >20%–30%.[4]

The main volcanic hazard at Taupō is from a massive explosive eruption which could create a natural disaster of extreme magnitude given the size of the present magma chamber and that its last eruption was the most severe worldwide in the last 5,000 years. However some of the 29 eruptions of various magnitudes in the last 30,000 years have been much smaller.[23] Many have been dome forming which may have contributed to lake features such as Motutaiko Island and the Horomatangi Reefs.

Earthquake and tsunami hazards also exist. While most earthquakes are relatively small and associated with magma shifts, the moderate earthquakes associated with eruptions or the numerous rift associated faults have historically produced tsunami events. The intra-rift Waihi fault for example has been associated with 6.5 magnitude earthquakes at recurrence intervals between 490 and 1380 years and at least one tsunami related to landslip at the Hipaua steaming cliffs.[24]

GNS Science continuously monitors Taupō using a network of seismographs and GPS stations.[23] The Horomatangi Reefs area of the lake is associated with active hydrothermal venting and high heat flow.[4] Monitoring of a volcano situated under a lake is challenging, and an eruption might occur with little or no meaningful notice.[23] Live data can be viewed on the GeoNet website.

See also

References

- ^ "NZTopMap:Motutaiko Island". Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ a b Dunbar, Nelia W.; Iverson, Nels A.; Van Eaton, Alexa R.; Sigl, Michael; Alloway, Brent V.; Kurbatov, Andrei V.; Mastin, Larry G.; McConnell, Joseph R.; Wilson, Colin J. N. (25 September 2017). "New Zealand supereruption provides time marker for the Last Glacial Maximum in Antarctica". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 12238. Bibcode:2017NatSR...712238D. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11758-0. PMC 5613013. PMID 28947829.

- ^ a b Hogg, Alan; Lowe, David J.; Palmer, Jonathan; Boswijk, Gretel; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk (2011). "Revised calendar date for the Taupo eruption derived by 14C wiggle-matching using a New Zealand kauri 14C calibration data set". The Holocene. 22 (4): 439–449. Bibcode:2012Holoc..22..439H. doi:10.1177/0959683611425551. hdl:10289/5936. S2CID 129928745.

- ^ a b c d e Illsley-Kemp, Finnigan; Barker, Simon J.; Wilson, Colin J. N.; Chamberlain, Calum J.; Hreinsdóttir, Sigrún; Ellis, Susan; Hamling, Ian J.; Savage, Martha K.; Mestel, Eleanor R. H.; Wadsworth, Fabian B. (1 June 2021). "Volcanic Unrest at Taupō Volcano in 2019: Causes, Mechanisms and Implications". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 22 (6): 1–27. Bibcode:2021GGG....2209803I. doi:10.1029/2021GC009803.

- ^ A continent on the move: New Zealand geoscience into the 21st century. Graham, Ian J. et al.; The Geological Society of New Zealand in association with GNS Science, 2008. ISBN 978-1-877480-00-3. page 66, 168.

- ^ "Taupo the volcano" (a single sheet pamphlet), C.J.N. Wilson and B.F. Houghton, Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences, c2004.

- ^ "Information from GNS Science on the Taupō Volcano". Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Bed of Lake Taupō rising and falling as magma moves around in active volcano below - study". Newshub. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ a b Manville, Vern; Wilson, Colin J. N. (2004). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui eruption, New Zealand: a review of the roles of volcanism and climate in the post-eruptive sedimentary response". New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics. 47 (3): 525–547. doi:10.1080/00288306.2004.9515074.

- ^ Wilson, Colin J. N. (2001). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui eruption, New Zealand: an introduction and overview". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 112 (1–4): 133–174. Bibcode:2001JVGR..112..133W. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(01)00239-6.

- ^ Wilson, Colin J. N.; et al. (2006). "The 26.5 ka Oruanui Eruption, Taupō Volcano, New Zealand: Development, Characteristics and Evacuation of a Large Rhyolitic Magma Body". Journal of Petrology. 47 (1): 35–69. Bibcode:2005JPet...47...35W. doi:10.1093/petrology/egi066.

- ^ "Taupo the eruption" (a single sheet pamphlet), C.J.N. Wilson and B.F. Houghton, Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences, c2004.

- ^ Wilson, C.J.N. and Walker, G.P.L., 1985. The Taupō eruption, New Zealand I. General aspects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, A314: 199–228.

- ^ Houghton, B.F. (2007). Field Guide – Taupo Volcanic Zone Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ von Lichtan, I.J.; White, J.D.L.; Manville, V.; Ohneiser, C. (2016). "Giant rafted pumice blocks from the most recent eruption of Taupo volcano, New Zealand: Insights from palaeomagnetic and textural data". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 318: 73–88. Bibcode:2016JVGR..318...73V. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2016.04.003.

- ^ Lake Taupō Official Site Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Herodian of Antioch. "Chapter 14". History of the Roman Empire. Vol. Book 1. Archived from the original on 16 September 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

Stars remained visible during the day; other stars, extending to an enormous length, seemed to be hanging in the middle of the sky.

- ^ Barton, John (2001). The First New Zealand Book? — an Eyewitness account of the Taupō eruption of AD 186. New Plymouth: Trustees of the Dalberton Library. ISBN 0-473-08268-3.

- ^ "Iridium: tracking down the extraterrestrial element in sedimentary clays". New Scientist: 58. 1989. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Sparks, R.J.; Melhuish, W.H.; McKee, J.W.A.; Ogden, J.; Palmer, J.G. (1995). "14C calibration in the Southern Hemisphere and the date of the last Taupō eruption: evidence from tree-ring sequences". Radiocarbon. 37 (2): 155–163. doi:10.1017/s0033822200030599.

- ^ Behr, Yannik (24 August 2022). "Volcanic Activity Bulletin TP – 2022/02: Earthquake activity continues and deformation observed at Taupō. Volcanic Alert Level remains at Level 0". GeoNet. New Zealand: GeoNet. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ "GeoNet Volcanic Activity Bulletin". www.geonet.org.nz. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ a b c "GeoNet volcano data underpins new research of Taupō volcano". Geonet NZ. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Gómez‐Vasconcelos, Martha; Villamor, Pilar; Procter, Jon; Palmer, Alan; Cronin, Shane; Wallace, Clel; Townsend, Dougal; Leonard, Graham (2018). "Characterisation of faults as earthquake sources from geomorphic data in the Tongariro Volcanic Complex, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 62: 131–142. doi:10.1080/00288306.2018.1548495. S2CID 134094861.

External links

- Lake-floor relief map, from Rowe, Dave; Shankar, Ude; James, Gavin; Waugh, B (July 2002). "Use of GIS to predict effects of water level on the spawning area for smelt, Retropinna retropinna, in Lake Taupo, New Zealand". Fisheries Management and Ecology. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 9 (4): 205–216. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2400.2002.00298.x. Retrieved 28 February 2018.. Same data exists in Rowe, Dave; James, Gavin; Macaulay, Gavin; Shankar, Ude (October 2002). "High-tech tools for tackling fisheries problems in lakes". Water & Atmosphere. NIWA. 10 (3): 24–25. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- Pages using the EasyTimeline extension

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1: long volume value

- Use dmy dates from April 2022

- Articles with short description

- Coordinates not on Wikidata

- Holocene calderas

- Pleistocene calderas

- Taupō Volcanic Zone

- Geology of New Zealand

- Calderas of New Zealand

- VEI-8 volcanoes

- VEI-7 volcanoes

- VEI-6 volcanoes

- Supervolcanoes

- Landforms of Waikato

- Tsunamis in New Zealand

- Lists of volcanic eruptions

- Lake Taupō