Solar deity

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of religion |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

A solar deity or sun deity is a deity who represents the Sun, or an aspect of it. Such deities are usually associated with power and strength. Solar deities and Sun worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms. The Sun is sometimes referred to by its Latin name Sol or by its Greek name Helios. The English word sun derives from Proto-Germanic *sunnǭ.[1]

Overview

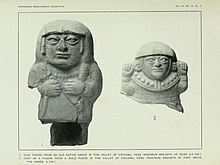

Predynasty Egyptian beliefs attribute Atum as the Sun god and Horus as god of the sky and Sun. As the Old Kingdom theocracy gained influence, early beliefs were incorporated into the expanding popularity of Ra and the Osiris-Horus mythology. Atum became Ra-Atum, the rays of the setting Sun. Osiris became the divine heir to Atum's power on Earth and passed his divine authority to his son, Horus.[2] Other early Egyptian myths imply that the Sun is incorporated with the lioness Sekhmet at night and is reflected in her eyes; or that the Sun is found within the cow Hathor during the night and reborn each morning as her son (bull).[3]

Mesopotamian Shamash played an important role during the Bronze Age, and "my Sun" was eventually used to address royalty. Similarly, South American cultures have a tradition of Sun worship as with the Incan Inti.[4]

In Germanic mythology, the solar deity is Sol; in Vedic, Surya; and in Greek, Helios (occasionally referred to as Titan) and (sometimes) as Apollo. In Proto-Indo-European mythology the sun appears to be a multilayered figure manifested as a goddess but also perceived as the eye of the sky father Dyeus.[5]

Solar myth

Three theories exercised great influence on nineteenth and early twentieth century mythography. The theories were the "solar mythology" of Alvin Boyd Kuhn and Max Müller, the tree worship of Mannhardt, and the totemism of J. F. McLennan.[6]

Müller's "solar mythology" was born from the study of Indo-European languages. Of them, Müller believed Archaic Sanskrit was the closest to the language spoken by the Aryans. Using the Sanskrit names for deities as a base, he applied Grimm's law to names for similar deities from different Indo-European groups to compare their etymological relationships to one another. In the comparison, Müller saw the similarities between the names and used these etymological similarities to explain the similarities between their roles as deities. Through the study, Müller concluded that the Sun having many different names led to the creation of multiple solar deities and their mythologies that were passed down from one group to another.[7]

R. F. Littledale criticized the Sun myth theory, pointing out that by his own principles, Max Müller was himself only a solar myth. Alfred Lyall delivered another attack on the same theory's assumption that tribal gods and heroes, such as those of Homer, were only reflections of the Sun myth by proving that the gods of certain Rajput clans were actual warriors who founded the clans a few centuries ago, and were the ancestors of the present chieftains.[8]

Solar vessels and Sun chariots

The Sun was sometimes envisioned as traveling through the sky in a boat. A prominent example is the solar barque used by Ra in ancient Egyptian mythology.[9] The Neolithic concept of a "solar barge" (also "solar bark", "solar barque", "solar boat" and "sun boat", a mythological representation of the Sun riding in a boat) is found in the later myths of ancient Egypt, with Ra and Horus. Several Egyptian kings were buried with ships that may have been intended to symbolize the solar barque,[10] including the Khufu ship that was buried at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza.[11]

Examples of solar vessels include:

- Neolithic petroglyphs which are interpreted as depicting solar barges.

- The many early Egyptian goddesses that were seen as sun deities, and the later gods Ra and Horus were depicted as riding in a solar barge. In Egyptian myths of the afterlife, Ra rides in an underground channel from west to east every night so that he can rise in the east the next morning.

- The Nebra sky disk, which is thought to show a depiction of a solar barge.

- Nordic Bronze Age petroglyphs, including those found in Tanumshede, often contain barges and sun crosses in different constellations.

The concept of the 'solar chariot' is younger than that of the solar barge and is typically Indo-European, corresponding with the Indo-European expansion after the invention of the chariot in the 2nd millennium BC. [12] The reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European religion features a 'solar chariot' or 'sun chariot' with which the Sun traverses the sky.[13]

Examples of solar chariots include:

- In Norse mythology, the chariot of the goddess Sól, drawn by Arvak and Alsvid. The Trundholm sun chariot dates to the Nordic Bronze Age, more than 2,500 years earlier than the Norse myth, but is often associated with it.

- Greek Helios (or Apollo) riding in a chariot.[14] (See also Phaëton)[15]

- Sol Invictus depicted riding a quadriga on the reverse of a Roman coin.[16]

- Hindu Surya riding in a chariot drawn by seven horses.

In Chinese culture, the sun chariot is associated with the passage of time. For instance, in the poem Suffering from the Shortness of Days, Li He of the Tang dynasty is hostile towards the legendary dragons that drew the sun chariot as a vehicle for the continuous progress of time.[17] The following is an excerpt from the poem:[17]

I will cut off the dragon's feet, chew the dragon's flesh,

so that they can't turn back in the morning or lie down at night.

Left to themselves the old won't die; the young won't cry.

The Sun was also compared to a wheel, for example, in Greek hēlíou kúklos, Sanskrit suryasya cakram, and Anglo-Saxon sunnan hweogul, all theorized to be reflexes of PIE *swelyosyo kukwelos. Scholarship also points to a possible reflex in poetic expressions in Ukrainian folk songs.[a][citation needed]

Gender

Solar deities are often thought of as male (and lunar deities as being female) but the opposite has often been the case.[19] In Germanic mythology, the Sun is female, and the Moon is male. Other European cultures that have sun goddesses include the Lithuanians (Saulė) and Latvians (Saule), the Finns (Päivätär, Beiwe) and the related Hungarians. Sun goddesses are found around the world in Australia (Bila, Wala); in Indian tribal religions (Bisal-Mariamma, Bomong, 'Ka Sgni) and Sri Lanka (Pattini); among the Hittites (Wurusemu), Egyptians (Hathor, Sekhmet), and Canaanites (Shapash); in the Canary Islands (Chaxiraxi, Magec); in Native America, among the Cherokee (Unelanuhi), Natchez (Oüa Chill/Uwahci∙ł), Inuit (Malina), and Miwok (He'-koo-lās); and in Asia among the Japanese (Amaterasu).[19]

The cobra (of Pharaoh, son of Ra), the lioness (daughter of Ra), and the cow (daughter of Ra), are the dominant symbols of the most ancient Egyptian deities. They were female and carried their relationship to the sun atop their heads, and their cults remained active throughout the history of the culture. Later another sun god (Aten) was established in the eighteenth dynasty on top of the other solar deities, before the "aberration" was stamped out and the old pantheon re-established. When male deities became associated with the sun in that culture, they began as the offspring of a mother (except Ra, King of the Gods who gave birth to himself).[citation needed]

World religions

Solar deities are revered in some of the major world religions.

Christianity

Church Fathers

The comparison of Christ with the astronomical Sun is common in ancient Christian writings.[20] By "the sun of righteousness" in Malachi 4 (Malachi 4:2) "the fathers, from Justin downward, and nearly all the earlier commentators understand Christ, who is supposed to be described as the rising sun".[21] The New Testament itself contains a hymn fragment in Ephesians 5: "Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ will shine on you."[22] Clement of Alexandria wrote of "the Sun of the Resurrection, he who was born before the dawn, whose beams give light".[23]

Purported Christianization of Sol Invictus

Christianization of Natalis Invicti

According to one hypothesis about Christmas, the date was set to 25 December because it was the date of the festival of Sol Invictus. The idea became popular especially in the 18th[24][25] and 19th centuries.[26][27][28]

The Philocalian calendar of AD 354 marks a festival of Natalis Invicti on 25 December. There is limited evidence that the festival was celebrated at around the time before the mid-4th century.[29][30]

The earliest-known example of the idea that Christians chose to celebrate the birth of Jesus on 25 December because it was the date of an already existing festival of the Sol Invictus was expressed in an annotation to a manuscript of a work by 12th-century Syrian bishop Jacob Bar-Salibi. The scribe who added it wrote: "It was a custom of the Pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnized on that day."[31][32][33][34]

Calculation hypothesis

In the judgment of the Church of England Liturgical Commission, this view has been seriously challenged[35] by a view based on an old tradition, according to which the date of Christmas was fixed at nine months after 25 March, the date of the vernal equinox, on which the Annunciation was celebrated.[36] The Jewish calendar date of 14 Nisan was believed to be that of creation,[37] as well as of the Exodus and so of Passover, and Christians held that the new creation, both the death of Jesus and the beginning of his human life, occurred on the same date, which some put at 25 March in the Julian calendar.[35][38][39][40]

It was a traditional Jewish belief that great men lived a whole number of years, without fractions, so that Jesus was considered to have been conceived on 25 March, as he died on 25 March, which was calculated to have coincided with 14 Nisan.[41] Sextus Julius Africanus (c.160 – c.240) gave 25 March as the day of creation and of the conception of Jesus.[42] The tractate De solstitia et aequinoctia conceptionis et nativitatis Domini nostri Iesu Christi et Iohannis Baptistae falsely attributed to John Chrysostom also argued that Jesus was conceived and crucified on the same day of the year and calculated this as 25 March.[36][40] A passage of the Commentary on the prophet Daniel by Hippolytus of Rome, written in about 204, has also been appealed to.[43]

Among those who have put forward this view are Louis Duchesne,[44] Thomas J. Talley,[45] David J. Rothenberg,[46] J. Neil Alexander,[47] and Hugh Wybrew.[48]

The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought also remarks on the uncertainty about the order of precedence between the celebrations of the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun and the birthday of Jesus: "This 'calculations' hypothesis potentially establishes 25 December as a Christian festival before Aurelian's decree, which, when promulgated, might have provided for the Christian feast both opportunity and challenge."[49] Susan K. Roll calls "most extreme" the unproven hypothesis that "would call Christmas point-blank a 'christianization' of Natalis Solis Invicti, a direct conscious appropriation of the pre-Christian feast, arbitrarily placed on the same calendar date, assimilating and adapting some of its cosmic symbolism and abruptly usurping any lingering habitual loyalty that newly-converted Christians might feel to the feasts of the state gods".[50]

Winter solstice hypothesis

Among scholars who view the celebration of the birth of Jesus on 25 December as motivated by choice of the winter solstice, rather than that he was conceived and died on 25 March, some reject the idea that this choice constituted a deliberate Christianization of a festival of the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun. For example, Michael Alan Anderson writes:

"Both the sun and Christ were said to be born on December 25. But while the solar associations with the birth of Christ created powerful metaphors, the surviving evidence does not support such a direct association with the Roman solar festivals. The earliest documentary evidence for the feast of Christmas makes no mention of the coincidence with the winter solstice. Thomas Talley has shown that, although the Emperor Aurelian's dedication of a temple to the sun god in the Campus Martius (C.E. 274) probably took place on the 'Birthday of the Invincible Sun' on December 25, the cult of the sun in pagan Rome ironically did not celebrate the winter solstice nor any of the other quarter-tense days, as one might expect. The origins of Christmas, then, may not be expressly rooted in the Roman festival."[51]

The same point is made by Hijmans:

"It is cosmic symbolism...which inspired the Church leadership in Rome to elect the southern solstice, December 25, as the birthday of Christ ... While they were aware that pagans called this day the 'birthday' of Sol Invictus, this did not concern them and it did not play any role in their choice of date for Christmas."[52]

He also states that:

"while the winter solstice on or around December 25 was well established in the Roman imperial calendar, there is no evidence that a religious celebration of Sol on that day antedated the celebration of Christmas".[53]

A study of Augustine of Hippo remarks that his exhortation in a Christmas sermon, "let us celebrate this day as a feast not for the sake of this sun, which is beheld by believers as much as by ourselves, but for the sake of him who created the sun", shows that he was aware of the coincidence of the celebration of Christmas and the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun, although this pagan festival was celebrated at only a few places and was originally a peculiarity of the Roman city calendar. It adds: "He also believes, however, that there is a reliable tradition which gives 25 December as the actual date of the birth of our Lord."[54]

In the 5th century, Pope Leo I (the Great) spoke in several sermons on the Feast of the Nativity of how the celebration of Christ's birth coincided with the increase of the Sun's position in the sky. An example is: "But this Nativity which is to be adored in heaven and on earth is suggested to us by no day more than this when, with the early light still shedding its rays on nature, there is borne in upon our senses the brightness of this wondrous mystery.[55]

Christian iconography

The charioteer in the mosaic of Mausoleum M has been interpreted by some as Christ by those who argue that Christians adopted the image of the Sun (Helios or Sol Invictus) to represent Christ. In this portrayal, he is a beardless figure with a flowing cloak in a chariot drawn by four white horses, as in the mosaic in Mausoleum M discovered under Saint Peter's Basilica and in an early-4th-century catacomb fresco.[57] The nimbus of the figure under Saint Peter's Basilica is rayed, as in traditional pre-Christian representations.[57] Clement of Alexandria had spoken of Christ driving his chariot across the sky.[58] This interpretation is doubted by others: "Only the cross-shaped nimbus makes the Christian significance apparent".[59] and the figure is seen by some simply as a representation of the sun with no explicit religious reference whatever, pagan or Christian.[60]

Life of Christ and astrological comparisons

Another speculation connects the biblical elements of Christ's life to those of a sun god.[61] The Christian gospels report that Jesus had 12 followers (Apostles),[62] which are claimed to be akin to the twelve zodiac constellations. When the Sun was in the house of Scorpio, Judas plotted with the chief priests and elders to arrest Jesus by kissing him. As the Sun exited Libra, it entered into the waiting arms of Scorpio to be kissed by Scorpio's bite.[63][unreliable source?][64][unreliable source?]

Many of the world's sacrificed godmen, such as Osiris and Mithra, have their traditional birthday on 25 December.[65] During this time,[clarification needed] people believed that the "sun god" had "died" for three days and was "born again" on 25 December.[66] After 25 December, the Sun supposedly moves 1 degree north, foreshadowing longer days.[67] The three days following 21 December remain the darkest days of the year where Jesus (the Sun) dies and remains unseen for three days.[68][unreliable source?][69][unreliable source?]

At the beginning of the first century, the Sun on the vernal equinox passed from Aries to Pisces (1 A.D. to 2150 A.D). That harmonizes with the mentioned lamb and fish in the gospels.[70][71] The man carrying a pitcher of water (Luke 22:10) is Aquarius, the water bearer, who is always seen as a man pouring out a pitcher of water. He represents the Age of Aquarius, the age after Pisces, and when the Sun leaves the Age of Pisces (Jesus), it will go into the House of Aquarius.[71][72]

Hinduism

Worship of Surya

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

The ritual of Surya Namaskār, performed by Hindus, is an elaborate set of hand gestures and body movements, designed to greet and revere the Sun.

In India, at Konark in the state of Odisha, a temple is dedicated to Surya. The Konark Sun Temple has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Surya is the most prominent of the navagrahas, or the nine celestial objects of the Hindus. Navagrahas can be found in almost all Hindu temples. There are further temples dedicated to Surya–one in Arasavalli, Srikakulam District in Andhra Pradesh, one in Gujarat at Modhera, and another in Rajasthan. The temple at Arasavalli was constructed in such a way that on the day of Radhasaptami, the Sun's rays directly fall on the feet of the Sri Suryanarayana Swami, the deity at the temple.

Chhath (Hindi: छठ, also called Dala Chhath) is an ancient Hindu festival dedicated to Surya, unique to Bihar, Jharkhand and the Terai. The major festival is also celebrated in the northeast region of India, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and parts of Chhattisgarh. Hymns to the Sun can be found in the Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism. Practiced in different parts of India, the worship of the Sun has been described in the Rigveda. In the state of Odisha, there is another festival called Samba Dashami which celebrates Surya.

The sun is prayed to by South Indians during the harvest festival.[73]

In Tamil Nadu, the Tamil people worship the sun god during the Tamil month of Thai, after a year of crop farming. The month is known as the harvesting month and people pay respects to the sun on the first day of the Thai month known as Thai pongal, or Pongal, which is a four-day celebration.[74] It is one of the few indigenous worships by the Tamil people, irrespective of religion.[75]

In other parts of India, the festival is celebrated as Makar Sankranti and is mostly worshiped by Hindu diaspora.[76]

Africa

The Tiv people consider the Sun to be the son of the Moon Awondo's daughter and the supreme being Awondo. The Barotse tribe believes that the Sun is inhabited by the sky god Nyambi and that the Moon is his wife. Some Sara people also worship the Sun. Even where the sun god is equated with the supreme being, in some African mythologies, they do not have any special functions or privileges as compared to other deities. The ancient Egyptian god of creation, Amun, is also believed to reside inside of the Sun. So is the Akan creator deity, Nyame, and the Dogon deity of creation, Nommo. Also in Egypt, there was a religion that worshiped the Sun directly, and was among the first monotheistic religions: Atenism.[77]

Ancient Egypt

Sun worship was prevalent in ancient Egyptian religion. The earliest deities associated with the Sun are all goddesses: Wadjet, Sekhmet, Hathor, Nut, Bast, Bat, and Menhit. First Hathor, and then Isis, give birth to and nurse Horus and Ra, respectively. Hathor the horned-cow is one of the 12 daughters of Ra, gifted with joy and is a wet-nurse to Horus.[78]

From at least the 4th Dynasty of ancient Egypt, the Sun was worshiped as the deity Re (pronounced probably as Riya, meaning simply 'the sun'), and portrayed as a falcon-headed god surmounted by the solar disk, and surrounded by a serpent. Re supposedly gave warmth to the living body, symbolized as an ankh: a "☥" shaped amulet with a looped upper half. The ankh, it was believed, was surrendered with death, but could be preserved in the corpse with appropriate mummification and funerary rites. The supremacy of Re in the Egyptian pantheon was at its highest with the 5th Dynasty, when open-air solar temples became common. In the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, Ra lost some of his preeminence to Osiris, lord of the West, and judge of the dead. In the New Empire period, the Sun became identified with the dung beetle, whose spherical ball of dung was identified with the Sun. In the form of the sun disc Aten, the Sun had a brief resurgence during the Amarna Period when it again became the preeminent, if not only, divinity for the Pharaoh Akhenaton.[79][80]

The Sun's movement across the sky represents a struggle between the Pharaoh's soul and an avatar of Osiris. Ra travels across the sky in his solar-boat; at dawn he drives away the demon king Apep.[81][82] The "solarisation" of several local gods (Hnum-Re, Min-Re, Amon-Re) reaches its peak in the period of the fifth dynasty.[83]

| ||

| Akhet (horizon) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

Rituals to the god Amun, who became identified with the sun god Ra, were often carried out on the top of temple pylons. A pylon mirrored the hieroglyph for 'horizon' or akhet, which was a depiction of two hills "between which the sun rose and set,"[84] associated with recreation and rebirth. On the first pylon of the temple of Isis at Philae, the pharaoh is shown slaying his enemies in the presence of Isis, Horus, and Hathor.[85]

In the eighteenth dynasty, the earliest-known monotheistic head of state, Akhenaten, changed the polytheistic religion of Egypt to a monotheistic one, Atenism. All other deities were replaced by the Aten, including Amun-Ra, the reigning sun god of Akhenaten's own region. Unlike other deities, Aten did not have multiple forms. His only image was a disk—a symbol of the Sun.[86]

Soon after Akhenaten's death, worship of the traditional deities was reestablished by the religious leaders (Ay the High-Priest of Amen-Ra, mentor of Tutankhaten/Tutankhamen) who had adopted the Aten during the reign of Akhenaten.[87]

Asia and Europe

Armenian mythology

In Armenian mythology and in the vicinity of Carahunge, the ancient site of interest in the field of archaeoastronomy, people worshiped a powerful deity or intelligence called Ara, embodied as the sun (Ar[88] or Arev). The ancient Armenians called themselves "children of the sun".[89] (Russian and Armenian archaeoastronomers have suggested that at Carahunge seventeen of the stones still standing were associated with observations of sunrise or sunset at the solstices and equinoxes.[90])

Baltic mythology

Those who practice Dievturība, beliefs of traditional Latvian culture, worship the Sun goddess Saule, known in traditional Lithuanian beliefs as Saulė. Saule is among the most important deities in Baltic mythology and traditions.[91]

Celtic mythology

The sun in Insular Celtic culture is assumed to have been feminine,[92][93] and several goddesses have been proposed as possibly solar in character.[94] In Continental Celtic culture, the sun gods, like Belenos, Grannos, and Lug, were masculine.[95][96][97]

In Irish, the name of the Sun, Grian, is feminine. The figure known as Áine is generally assumed to have been either synonymous with her, or her sister, assuming the role of Summer Sun while Grian was the Winter Sun.[98] Similarly, Étaín has at times been considered to be another theonym associated with the Sun; if this is the case, then the pan-Celtic Epona might also have been originally solar in nature,[98] though Roman syncretism pushed her towards a lunar role.[citation needed]

The British Sulis has a name cognate with that of other Indo-European solar deities such as the Greek Helios and Indic Surya,[99][100] and bears some solar traits like the association with the eye as well as epithets associated with light. The theonym Sulevia, which is more widespread and probably unrelated to Sulis,[101] is sometimes taken to have suggested a pan-Celtic role as a solar goddess.[92]

The Welsh Olwen has at times been considered a vestige of the local sun goddess, in part due to the possible etymological association[102] with the wheel and the colors gold, white and red.[92]

Brighid has at times been argued as having had a solar nature, fitting her role as a goddess of fire and light.[92]

Chinese mythology

In Chinese mythology (cosmology), there were originally ten suns in the sky, who were all brothers. They were supposed to emerge one at a time as commanded by the Jade Emperor. They were all very young and loved to fool around. Once they decided to all go into the sky to play, all at once. This made the world too hot for anything to grow. A hero named Hou Yi, honored to this day, shot down nine of them with a bow and arrow to save the people of the Earth.[103]

In another myth, a solar eclipse was said to be caused by a magical dog or dragon biting off a piece of the Sun. The referenced event is said to have occurred around 2136 BC; two royal astronomers, Ho and Hi, were executed for failing to predict the eclipse. There was a tradition in China to make lots of loud celebratory sounds during a solar eclipse to scare the sacred beast away.[104]

The Deity of the Sun in Chinese mythology is Ri Gong Tai Yang Xing Jun (Tai Yang Gong/Grandfather Sun) or Star Lord of the Solar Palace, Lord of the Sun. In some mythologies, Tai Yang Xing Jun is believed to be Hou Yi.[citation needed]

Tai Yang Xing Jun is usually depicted with the Star Lord of the Lunar Palace, Lord of the Moon, Yue Gong Tai Yin Xing Jun (Tai Yin Niang Niang/Lady Tai Yin). Worship of the moon goddess Chang'e and her festivals are very popular among followers of Chinese folk religion and Taoism. The goddess and her holy days are ingrained in Chinese popular culture.[105]

Germanic mythology

In Germanic mythology, the sun is personified by Sol. The corresponding Old English name is Siȝel [ˈsijel], continuing Proto-Germanic *Sôwilô or *Saewelô. The Old High German Sun goddess is Sunna. In the Norse traditions, Sól rode through the sky on her chariot every day, pulled by two horses named Arvak and Alsvid. Sól also was called Sunna and Frau Sunne.[citation needed]

First century historian Tacitus, in his book Germania, mentioned that "beyond the Suiones [tribe]" a sea was located where the sun maintained its brilliance from its rising to its sunset, and that "[the] popular belief" was that "the sound of its emergence was audible" and "the form of its horses visible".[106][107][108]

Greco-Roman world

Hellenistic mythology

In Greek mythology, Helios, a Titan, was the personification of the Sun; however, with the notable exception of the island of Rhodes and nearby parts of southwestern Anatolia,[b] he was a relatively minor deity. The Ancient Greeks also associated the Sun with Apollo, the god of enlightenment. Apollo (along with Helios) was sometimes depicted as driving a fiery chariot.[109]

The Greek astronomer Thales of Miletus described the scientific properties of the Sun and Moon, making their godship unnecessary.[110] Anaxagoras was arrested in 434 BC and banished from Athens for denying the existence of a solar or lunar deity.[111] The titular character of Sophocles' Electra refers to the Sun as "All-seeing". Hermetic author Hermes Trismegistus calls the Sun "God Visible".[112]

The Minotaur has been interpreted as a solar deity (as Moloch or Chronos),[113] including by Arthur Bernard Cook, who considers both Minos and Minotaur as aspects of the sun god of the Cretans, who depicted the sun as a bull.[citation needed]

Roman mythology

During the Roman Empire, a festival of the birth of the Unconquered Sun (or Dies Natalis Solis Invicti) was celebrated on the winter solstice—the "rebirth" of the Sun—which occurred on 25 December of the Julian calendar. In late antiquity, the theological centrality of the Sun in some Imperial religious systems suggest a form of a "solar monotheism". The religious commemorations on 25 December were replaced under Christian domination of the Empire with the birthday of Christ.[114]

Modern influence

Copernicus describing the Sun mythologically, drawing from Greco-Roman examples:

In the middle of all sits the Sun on his throne. In this loveliest of temples, could we place the luminary in any more appropriate place so that he may light the whole simultaneously. Rightly is he called the Lamp, the Mind, the Ruler of the Universe: Hermes Trismegistus entitles him the God Visible. Sophocles' Electra names him the All-seeing. Thus does the Sun sit as upon a royal dais ruling his children the planets which circle about him.[112]

Pre-Islamic Arabia

The concept of the sun in Pre-Islamic Arabia, was abolished only under Muhammad.[115] The Arabian solar deity appears to have been a goddess, Shams/Shamsun, most likely related to the Canaanite Shapash and broader middle-eastern Shamash. She was the patron goddess of Himyar, and possibly exalted by the Sabaeans .[116][unreliable source?][117][118]

Yazidism

The Yazidis pray facing the sun, as they believe sunlight to be an emanation of God and that the world was created by light.[119]

Americas

Aztec mythology

In Aztec mythology, Tonatiuh (Nahuatl languages: Ollin Tonatiuh, "Movement of the Sun") was the sun god. The Aztec people considered him the leader of Tollan (heaven). He was also known as the fifth sun, because the Aztecs believed that he was the sun that took over when the fourth sun was expelled from the sky. According to their cosmology, each sun was a god with its own cosmic era. According to the Aztecs, they were still in Tonatiuh's era. According to the Aztec creation myth, the god demanded human sacrifice as tribute and without it would refuse to move through the sky. The Aztecs were fascinated by the Sun and carefully observed it, and had a solar calendar similar to that of the Maya. Many of today's remaining Aztec monuments have structures aligned with the Sun.[120]

In the Aztec calendar, Tonatiuh is the lord of the thirteen days from 1 Death to 13 Flint. The preceding thirteen days are ruled over by Chalchiuhtlicue, and the following thirteen by Tlaloc.[citation needed]

Incan mythology

Inti is the ancient Incan sun god. He is revered as the national patron of the Inca state. Although most consider Inti the sun god, he is more appropriately viewed as a cluster of solar aspects, since the Inca divided his identity according to the stages of the sun.[citation needed]

New religious movements

Solar deities are revered in many new religious movements.

Thelema

Thelema adapts its gods and goddesses from Ancient Egyptian religion, particularly those named in the Stele of Revealing, among whom is the Sun god Ra-Hoor-Khuit, a form of Horus. Ra-Hoor-Khuit is one of the principal deities described in Aleister Crowley's Liber AL vel Legis.[121]

Theosophy

The primary local deity in theosophy is the Solar Logos, "the consciousness of the sun".[122]

Other

In Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches, folklorist Charles Leland alleges that a pagan group of witches in Tuscany, Italy viewed Lucifer as the god of the Sun and consort of the goddess Diana, whose daughter is the messiah Aradia.[123]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Колесом сонечко на гору йде ("The Sun goes up, as a wheel") and Горою сонечко колує ("Above (us) the Sun is wheeling/rotating").[18]

- ^ see Colossus of Rhodes.

References

- ^ In most romance languages the word for "sun" is masculine (e.g. le soleil in French, el sol in Spanish, Il Sole in Italian). In most Germanic languages it is feminine (e.g. Die Sonne in German). In Proto-Indo-European, its gender was inanimate.

- ^ Ancient Civilizations- Egypt- Land and lives of Pharaohs revealed. Global Book Publishing. 30 October 2005. p. 79. ISBN 1740480562.

- ^ "Ancient Egyptian Gods & Goddesses Facts For Kids". History for kids. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Minster, Christopher (30 May 2019). "All About the Inca Sun God". ThoughtCo.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sick, David (2004). "Mit(h)ra(s) and the Myths of the Sun". Numen. 51 (4): 432–467. doi:10.1163/1568527042500140.

- ^ William Ridgeway (1915). "Solar Myths, Tree Spirits, and Totems, The Dramas and Dramatic Dances of Non-European Races". Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–19. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Carrol, Michael P. (1985). "Some third thoughts on Max Müller and solar mythology". European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie. 26 (2): 263–281. JSTOR 23997047. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ William Ridgeway (1915). "Solar Myths, Tree Spirits, and Totems, The Dramas and Dramatic Dances of Non-European Races". Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–19. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Baines, John R. (2004). "Visual Representation". In Johnston, Sarah Iles (ed.). Religions of the ancient world : a guide. Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 600. ISBN 9780674015173. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Egypt solar boats". solarnavigator.net.

- ^ Siliotti, Alberto; Hawass, Zahi (1997). Guide to the Pyramids of Egypt. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Feldman, Marian H.; Sauvage, Caroline (2010). "Objects of Prestige? Chariots in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean and Near East". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. 20: 67–181. doi:10.1553/AEundL20s67. JSTOR 23789937. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Kristiansen, Kristian (2005). "The Nebra find and early Indo-European religion". Congresses of the Halle State Museum for Prehistory. Halle State Museum of Prehistory. 5 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ "Helios". Theoi.com. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ "Helios & Phaethon". Thanasis.com. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Image of Probus Coin

- ^ a b Bien, Gloria (2012). Baudelaire in China a Study in Literary Reception. Lanham: University of Delaware. p. 20. ISBN 9781611493900.

- ^ Назаров, Н. А. 2015. "Індоєвропейське походження формул українського фольклору: сучасна інтерпретація спостережень О. О. Потебні". In: Мовознавство 6: 66–71.

- ^ a b Monaghan (2010), pp. xix–xxi.

- ^ Hartmut Miethe, Hilde Heyduck-Huth, Jesus (Taylor & Francis), p. 104

- ^ Carl Friedrich Keil, Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament (Eerdmans 1969), vol. 25, p. 468;

- ^ Ephesians 5:14

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Protreptius 9:84, quoted in David R. Cartlidge, James Keith Elliott, The Art of Christian Legend (Routledge 2001 ISBN 978-0-41523392-7), p. 64

- ^ Sir Edward Burnett Tylor, Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom, Volume 2, p. 270; John Murray, London, 1871; revised edition 1889.

- ^ Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Volume 3, 1885, T and T Clark, Edinburgh, page 396; see also Volume 4 in the 3rd edition, 1910 (Charles Scribner's Sons, NY).

- ^ Anderson, Michael Alan (2008). Symbols of Saints. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-54956551-2.

- ^ "The Day God Took Flesh". Melkite Eparchy of Newton of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church. 25 March 2012.

- ^ Martindale, Cyril (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Wallraff 2001: 174–177. Hoey (1939: 480) writes: "An inscription of unique interest from the reign of Licinius embodies the official prescription for the annual celebration by his army of a festival of Sol Invictus on December 19". The inscription (Dessau, Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 8940) actually prescribes an annual offering to Sol on November 18 (die XIV Kal(endis) Decemb(ribus), i.e. on the fourteenth day before the Kalends of December).

- ^ Text at [1] Parts 6 and 12 respectively.

- ^ (cited in Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Ramsay MacMullen. Yale:1997, p. 155)

- ^ Michael Alan Anderson, Symbols of Saints (ProQuest 2008 ISBN 978-0-54956551-2), p. 45

- ^ "» Feast of the Annunciation". melkite.org.

- ^ 1908 Catholic Encyclopedia: Christmas: Natalis Invicti

- ^ a b "Although this view is still very common, it has been seriously challenged" – Church of England Liturgical Commission, The Promise of His Glory: Services and Prayers for the Season from All Saints to Candlemas (Church House Publishing 1991 ISBN 978-0-71513738-3) quoted in The Date of Christmas and Epiphany

- ^ a b Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article "Christmas"

- ^ See discussion in the Talmud (Avraham Yaakov Finkel, Ein Yaakov (Jason Aronson 1999 ISBN 978-1-46162824-8), pp. 240–241), and Aryeh Kaplan's chapter, "The Shofar of Mercy", on the apparent contradiction between that tradition and the Jewish celebration of creation on 1 Tishrei.

- ^ Alexander V. G. Allen, Christian Institutions (Scribner, New York 1897), p. 474

- ^ Frank C. Seen, The People's Work (Fortress Press 2010 ISBN 9781451408010), p.72

- ^ a b Frank C. Senn, Introduction to Christian Liturgy (Fortress Press 2012 ISBN 978-0-80069885-0), p. 114]

- ^ William J. Colinge, Historical Dictionary of Catholicism (Scarecrow Press 2012 ISBN 978-0-81085755-1), p. 99]

- ^ Joseph F. Kelly, The Origins of Christmas (Liturgical Press 2004 ISBN 978-0-81462984-0), p. 60

- ^ "Hippolytus and December 25th as the date of Jesus' birth" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Christian Worship: Its Origin and Evolution (London: SPCK, 1903), pp 261–265)

- ^ The Origins of the Liturgical Year (New York: Pueblo, 1986), pp. 87–103

- ^ The Flower of Paradise (Oxford University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-19539971-4), p. 87

- ^ Waiting for the Coming: The Liturgical Meaning of Advent, Christmas, Epiphany (Washington, D.C.: Pastoral Press, 1993), pp. 46–51

- ^ Orthodox Feasts of Jesus Christ & the Virgin Mary (St Vladimir's Seminary Press 1997 ISBN 978-0-88141203-1), p. 20

- ^ Adrian Hastings, Alistair Mason, Hugh Pyper (editors), The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought (Oxford University Press 2000 ISBN 978-0-19860024-4), p. 114

- ^ Susan K. Roll, Toward the Origin of Christmas (Kempen 1995 ISBN 90-390-0531-1), p. 107

- ^ Michael Alan Anderson, Symbols of Saints (ProQuest 2008 ISBN 978-0-54956551-2), pp. 45–46

- ^ Hijmans (2009), p. 595.

- ^ Hijmans (2009), p. 588.

- ^ F. van der Meer, Brian Battershaw, G. R. Lamb, Augustine the Bishop: The Life and Work of a Father of the Church (Sheed & Ward 1961), pp. 292–293

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: Sermon 26 (Leo the Great)". www.newadvent.org.

- ^ "Loading..." www.saintpetersbasilica.org.

- ^ a b Weitzmann, Kurt (1979). Age of Spirituality. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 522. ISBN 978-0-87099179-0.

- ^ Webb, Matilda (2001). The Churches and Catacombs of Early Christian Rome. Sussex Academic Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-90221058-2.

- ^ Kemp, Martin (2000). The Oxford History of Western Art. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19860012-1., emphasis added

- ^ Hijmans 2009, p. 567-578.

- ^ Tester, Jim (1999). A History of Western Astrology. Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press.

- ^ McKnight, Scot (2001). "Jesus and the Twelve" (PDF). Bulletin for Biblical Research. 11 (2): 203–231. doi:10.2307/26422271. JSTOR 26422271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Acharya S/D.M. Murdock (2011). "Origins of Christianity" (PDF). Stellar House Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Nicholas Campion, The Book of World Horoscopes, The Wessex Astrologer, 1999, p. 489 clearly refers to both conventions adopted by many astrologers basing the Ages on either the zodiacal constellations or the sidereal signs.

- ^ Martínez, Antonio Marco (26 December 2014). "Mithra, god of the sun, was born on December 25, day of the winter solstice". History of Greece and Rome. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Declercq, Georges (2000). Anno Domini: The Origins of the Christian Era. Brepols Essays in European Culture. Belgium: Turnhout. ISBN 9782503510507.

- ^ Kuhn, Alvin Boyd (1996). "The Great Myth of the SUN-GODS". Mountain Man Graphics, Australia. Retrieved 11 September 2017. Note: This is a reprint; Kuhn died in 1963.

- ^ "Gospel Zodiac". The Unspoken Bible. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Elie, Benedict. "Aquarius Pisces Age". Astro Software. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Origins Zodiac Bible Code". US Bible. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Aquarius". Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Albert Amao, Aquarian Age & The Andean Prophecy, AuthorHouse, 2007, p. 56

- ^ Jain Chanchreek; K.L. Chanchreek; M.K. Jain (2007). Encyclopaedia of Great Festivals. Shree Publishers. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-81-8329-191-0.

- ^ "502 Bad Gateway nginx openresty 208.80.154.49". www.pongal-festival.com.

- ^ "Tamizhs festival". ntyo.org. Archived from the original on 27 December 2001. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Different festivals being celebrated today signify India's vibrant cultural diversity: PM Modi". The Hindu. PTI. 14 January 2022. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Akhenaten". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Kamrin, Janice (March 2015). "Papyrus in Ancient Egypt". The Metropolitan Museum.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Teeter, Emily (2011). Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521848558.

- ^ Frankfort, Henri (2011). Ancient Egyptian Religion: an Interpretation. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486411385.

- ^ Assman, Jan (2004). "Monotheism and Polytheism". In Johnston, Sarah Iles (ed.). Religions of the ancient world : a guide. Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780674015173. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Collins, John J. (2004). "Cosmology: Time and History". In Johnston, Sarah Iles (ed.). Religions of the ancient world : a guide. Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780674015173. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Kockel, Ullrich (2010), "Fifth Journey — Towards Castalia: To Re-Place Europe", Re-Visioning Europe, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 155–188, doi:10.1057/9780230282988_6, ISBN 978-1-349-52060-2, retrieved 17 October 2022

- ^ Wilkinson, op. cit., p.195

- ^ "Temple of Isis at Philae | Ancient Egypt Online". Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Amarna Period of Egypt". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 128–9. ISBN 978-0-19-521952-4.

- ^ Herouni, Paris M. (2004). Armenians and old Armenia: archaeoastronomy, linguistics, oldest history. Tigran Metz Publishing House. p. 127. ISBN 9789994101016.

- ^ Boettiger, Louis Angelo (1918). Armenian Legends and Festivals. University of Minnesota.

- ^ González-Garcia, A. César (2014), "Carahunge – A Critical Assessment", in Ruggles, Clive L. N. (ed.), Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy, New York: Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 1453–1460, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_140, ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1

- ^ Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. "Saule (Baltic deity)". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d Patricia Monaghan, The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore, page 433.

- ^ Koch, John T., Celtic Culture: Aberdeen breviary-celticism, page 1636.

- ^ "(...) the Celtic Sun-deities, however, were often (perhaps originally) feminine". Jones, Prudence; Pennick, Nigel (1995). A History of Pagan Europe. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-136-14172-0.

- ^ X., Delamarre (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise : une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (2e éd. rev. et augm ed.). Paris: Errance. pp. 72 & 183 & 211. ISBN 9782877723695. OCLC 354152038.

- ^ Media, Adams (2 December 2016). The Book of Celtic Myths: From the Mystic Might of the Celtic Warriors to the Magic of the Fey Folk, the Storied History and Folklore of Ireland, Scotland, Brittany, and Wales. F+W Media, Inc. p. 45. ISBN 9781507200872. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ MacCulloch, J. A. (1 August 2005). The Celtic and Scandinavian Religions. Chicago Review Press. p. 31. ISBN 9781613732298.

- ^ a b MacKillop (1998), pp. 10, 70, 92.

- ^ Delamarre, Xavier, Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, Errance, 2003, p. 287

- ^ Zair, Nicholas, Reflexes of the Proto-Indo-European Laryngeals in Celtic, Brill, 2012, p. 120

- ^ Nicole Jufer & Thierry Luginbühl (2001). Les dieux gaulois : répertoire des noms de divinités celtiques connus par l'épigraphie, les textes antiques et la toponymie. Editions Errance, Paris. pp. 15, 64.

- ^ Simon Andrew Stirling, The Grail: Relic of an Ancient Religion, 2015

- ^ Hamilton, Mae. "Hou Yi". Mythopedia. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Waldek, Stefanie (30 August 2018). "How 5 Ancient Cultures Explaiined Solar Eclipses". History.com. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Hamilton, Mae. "Chang'e". Mythopedia. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ "TACITUS, Germania LCL 35: 206-20". www.loebclassics.com.

- ^ Beare, W. (1964). "Tacitus on the Germans". Greece & Rome. 11 (1): 64–76. doi:10.1017/S0017383500012675. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 642633. S2CID 163536034.

- ^ O'Gorman, Ellen (1993). "No Place Like Rome: Identity and Difference in the Germania of Tacitus". Ramus. 22 (2): 135–154. doi:10.1017/S0048671X00002484. S2CID 131482053.

- ^ Gill, N.S. (3 December 2019). "Everything you need to know about Apollo". Thought Co. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 143.

- ^ Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 145.

- ^ a b Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

- ^ Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 137.

- ^ "Sun worship." Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009

- ^ "The Sun and the Moon are from among the evidences of God. They do not eclipse because of someone's death or life." Muhammad Husayn Haykal, Translated by Isma'il Razi A. al-Faruqi, The Life of Muhammad, American Trush Publications, 1976, ISBN 0-89259-002-5 [2]

- ^ Yoel Natan, Moon-o-theism, Volume I of II, 2006

- ^ Julian Baldick (1998). Black God. Syracuse University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0815605226.

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, 1999 – 1181 páginas

- ^ "Emerging from Isis genocide, Yazidis in Armenia open religion's biggest ever temple". Independent. 31 October 2019.

- ^ Biblioteca Porrúa. Imprenta del Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnología, ed. (1905). Diccionario de Mitología Nahua (in Spanish). México. pp. 648, 649, 650. ISBN 978-9684327955.

- ^ Crowley, Aleister (1904). Liber Al vel Legis.

- ^ Powell, A.E. The Solar System London:1930 The Theosophical Publishing House (A Complete Outline of the Theosophical Scheme of Evolution). Lucifer, represented by the sun, the light.

- ^ Charles Leland (1899). Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches. D. Nutt. ISBN 1-56414-679-0. Retrieved 30 December 2021. Chapter I

Bibliography

- Azize, Joseph (2005). The Phoenician Solar Theology: an investigation into the Phoenician opinion of the sun found in Julian's Hymn to King Helios (1st ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-210-6.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta (1962). Man and the Sun. Gaithersburg, MD: SolPub Co.

- Hijmans, Steven E. (2009). Sol: the sun in the art and religions of Rome (PDF) (Thesis). ISBN 978-90-367-3931-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Kaul, Flemming (1998). Ships on Bronzes: a study in Bronze Age religion and iconography. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark, Dept. of Danish Collections. ISBN 87-89384-66-0.

- MacKillop, James (1998). Dictionary of Celtic mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198691570.

- McCrickard, Janet E. (1990). Eclipse of the Sun: an investigation into Sun and Moon myths. Glastonbury, Somerset: Gothic Image. ISBN 0-906362-13-X.

- Monaghan, Patricia (1994). O Mother Sun!: A New View of the Cosmic Feminine. Freedom, CA: Crossing Press. ISBN 0-89594-722-6.

- Monaghan, Patricia (2010). Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood. ISBN 9780313349904.

- Olcott, William Tyler (2003) [1914]. Sun Lore of All Ages: A Collection of Myths and Legends Concerning the Sun and Its Worship. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0-543-96027-7.

- Singh, Ranjan Kumar (2010). Surya: the God and His Abode (1st ed.). Patna, Bihar, India: Parijat. ISBN 978-81-903561-7-6.

External links

- The Worship of the Sun Among the Aryan Peoples of Antiquity by Sir James G. Frazer (from archive.org)

- The Sun God Ra and Ancient Egypt

- The Sun God and the Wind Deity at Kizil by Tianshu Zhu, in Transoxiana Eran ud Aneran, Webfestschrift Marshak 2003.

- Comparison between the Egyptian Hymn of Aten and modern scientific conceptions

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Articles incorporating a citation from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with Wikisource reference

- CS1 maint: others

- CS1 errors: generic name

- CS1 Spanish-language sources (es)

- Articles with short description

- Use dmy dates from April 2020

- Articles lacking reliable references from September 2021

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles needing additional references from September 2021

- All articles needing additional references

- Articles with multiple maintenance issues

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing Sanskrit-language text

- Articles containing Old English (ca. 450-1100)-language text

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2021

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2021

- Articles containing Hindi-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2020

- Articles with text in Nahuatl languages

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- AC with 0 elements

- Solar deities

- Solar gods

- Solar goddesses

- Comparative mythology

- Mythological archetypes