Stratospheric aerosol injection

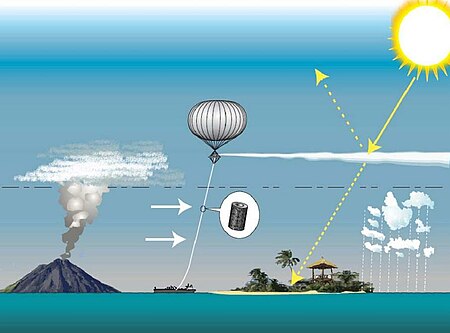

Stratospheric aerosol injection is a proposed method of solar geoengineering (or solar radiation modification) to reduce global warming. This would introduce aerosols into the stratosphere to create a cooling effect via global dimming, which occurs naturally from volcanic eruptions.[1] It appears that stratospheric aerosol injection, at a moderate intensity, could counter most changes to temperature and precipitation, take effect rapidly, have low direct implementation costs, and be reversible in its direct climatic effects.[2] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concludes that it "is the most-researched [solar geoengineering] method, with high agreement that it could limit warming to below 1.5°C."[3] However, like other solar geoengineering approaches, stratospheric aerosol injection would do so imperfectly and other effects are possible,[4] particularly if used in a suboptimal manner.[5]

Various forms of sulfur have been shown to cool the planet after large volcanic eruptions.[6] However, as of 2021, there has been little research and existing natural aerosols in the stratosphere are not well understood.[7] so there is no leading candidate material. Alumina, calcite and salt are also under consideration.[8][9] The leading proposed method of delivery is custom aircraft.[10]

Methods

Materials

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: seems sulfur no longer considered? add more detail on other materials. (August 2021) |

Various forms of sulfur were proposed as the injected substance, as this is in part how volcanic eruptions cool the planet.[6] Precursor gases such as sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide have been considered. According to estimates, "one kilogram of well placed sulfur in the stratosphere would roughly offset the warming effect of several hundred thousand kilograms of carbon dioxide."[11] One study calculated the impact of injecting sulfate particles, or aerosols, every one to four years into the stratosphere in amounts equal to those lofted by the volcanic eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991,[12] but did not address the many technical and political challenges involved in potential solar geoengineering efforts.[13] Use of gaseous sulfuric acid appears to reduce the problem of aerosol growth.[10] Materials such as photophoretic particles, titanium dioxide, and diamond are also under consideration.[14][15][16]

Delivery

Various techniques have been proposed for delivering the aerosol or precursor gases.[1] The required altitude to enter the stratosphere is the height of the tropopause, which varies from 11 kilometres (6.8 mi/36,000 ft) at the poles to 17 kilometers (11 mi/58,000 ft) at the equator.

- Civilian aircraft including the Boeing 747–400 and Gulfstream G550/650, C-37A could be modified at relatively low cost to deliver sufficient amounts of required material according to one study,[17] but a later metastudy suggests a new aircraft would be needed but easy to develop.[18]

- Military aircraft such as the F15-C variant of the F-15 Eagle have the necessary flight ceiling, but limited payload. Military tanker aircraft such as the KC-135 Stratotanker and KC-10 Extender also have the necessary ceiling and have greater payload capacity.[19]

- Modified artillery might have the necessary capability,[20] but requires a polluting and expensive propellant charge to loft the payload. Railgun artillery could be a non-polluting alternative.

- High-altitude balloons can be used to lift precursor gases, in tanks, bladders or in the balloons' envelope.

Injection system

The latitude and distribution of injection locations has been discussed by various authors. Whilst a near-equatorial injection regime will allow particles to enter the rising leg of the Brewer-Dobson circulation, several studies have concluded that a broader, and higher-latitude, injection regime will reduce injection mass flow rates and/or yield climatic benefits.[21][22] Concentration of precursor injection in a single longitude appears to be beneficial, with condensation onto existing particles reduced, giving better control of the size distribution of aerosols resulting.[23] The long residence time of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere may require a millennium-timescale commitment to SRM[24] if aggressive emissions abatement is not pursued simultaneously.

Aerosol formation

Primary aerosol formation, also known as homogeneous aerosol formation, results when gaseous SO

2 combines with oxygen and water to form aqueous sulfuric acid (H2SO4). This acidic liquid solution is in the form of a vapor and condenses onto particles of solid matter, either meteoritic in origin or from dust carried from the surface to the stratosphere. Secondary or heterogeneous aerosol formation occurs when H2SO4 vapor condenses onto existing aerosol particles. Existing aerosol particles or droplets also run into each other, creating larger particles or droplets in a process known as coagulation. Warmer atmospheric temperatures also lead to larger particles. These larger particles would be less effective at scattering sunlight because the peak light scattering is achieved by particles with a diameter of 0.3 μm.[14]

Advantages of the technique

The advantages of this approach in comparison to other possible means of solar geoengineering are:

- Mimics a natural process:[25] Stratospheric sulfur aerosols are created by existing natural processes (especially volcanoes), whose impacts have been studied via observations.[26] This contrasts with other, more speculative solar geoengineering techniques which do not have natural analogs (e.g., space sunshade).

- Technological feasibility: In contrast to other proposed solar geoengineering techniques, such as marine cloud brightening, much of the required technology is pre-existing: chemical manufacturing, artillery shells, high-altitude aircraft, weather balloons, etc.[6] Unsolved technical challenges include methods to deliver the material in controlled diameter with good scattering properties.

- Scalability: Some solar geoengineering techniques, such as cool roofs and ice protection, can only provide a limited intervention in the climate due to insufficient scale—one cannot reduce the temperature by more than a certain amount with each technique. Research has suggested that this technique may have a high radiative 'forcing potential'.[27]

Uncertainties

It is uncertain how effective any solar geoengineering technique would be, due to the difficulties modeling their impacts and the complex nature of the global climate system. Certain efficacy issues are specific to stratospheric aerosols.

- Lifespan of aerosols: Tropospheric sulfur aerosols are short-lived.[28] Delivery of particles into the lower stratosphere in the arctic will typically ensure that they remain aloft only for a few weeks or months, as air in this region is predominantly descending. To ensure endurance, higher-altitude delivery is needed, ensuring a typical endurance of several years by enabling injection into the rising leg of the Brewer-Dobson circulation above the tropical tropopause. Further, sizing of particles is crucial to their endurance.[29]

- Aerosol delivery: There are two proposals for how to create a stratospheric sulfate aerosol cloud, either through the release of a precursor gas (SO

2) or the direct release of sulfuric acid (H

2SO

4) and these face different challenges.[30] If SO

2 gas is released it will oxidize to form H

2SO

4 and then condense to form droplets far from the injection site.[31] Releasing SO

2 would not allow control over the size of the particles that are formed but would not require a sophisticated release mechanism. Simulations suggest that as the SO

2 release rate is increased there would be diminishing returns on the cooling effect, as larger particles would be formed which have a shorter lifetime and are less effective scatterers of light.[32] If H

2SO

4 is released directly then the aerosol particles would form very quickly and in principle the particle size could be controlled although the engineering requirements for this are uncertain. Assuming a technology for direct H

2SO

4 release could be conceived and developed, it would allow control over the particle size to possibly alleviate some of the inefficiencies associated with SO

2 release.[30]

Cost

Early studies suggest that stratospheric aerosol injection might have a relatively low direct cost. The annual cost of delivering 5 million tons of an albedo enhancing aerosol (sufficient to offset the expected warming over the next century) to an altitude of 20 to 30 km is estimated at US$2 billion to 8 billion.[33] In comparison, the annual cost estimates for climate damage or emission mitigation range from US$200 billion to 2 trillion.[33]

A 2016 study finds the cost per 1 W/m2 of cooling to be between 5–50 billion USD/yr.[34] Because larger particles are less efficient at cooling and drop out of the sky faster, the unit-cooling cost is expected to increase over time as increased dose leads to larger, but less efficient, particles by mechanism such as coalescence and Ostwald ripening.[35] Assume RCP8.5, -5.5 W/m2 of cooling would be required by 2100 to maintain 2020 climate. At the dose level required to provide this cooling, the net efficiency per mass of injected aerosols would reduce to below 50% compared to low-level deployment (below 1W/m2).[36] At a total dose of -5.5 W/m2, the cost would be between 55-550 billion USD/yr when efficiency reduction is also taken into account, bringing annual expenditure to levels comparable to other mitigation alternatives.

Other possible side effects

Solar geoengineering in general poses various problems and risks. However, certain problems are specific to or more pronounced with stratospheric sulfide injection.[37]

- Ozone depletion: is a potential side effect of sulfur aerosols;[38][39] and these concerns have been supported by modelling.[40] However, this may only occur if high enough quantities of aerosols drift to, or are deposited in, Polar stratospheric clouds before the levels of CFCs and other ozone destroying gases fall naturally to safe levels because stratospheric aerosols, together with the ozone destroying gases, are responsible for ozone depletion.[41] The injection of other aerosols that may be safer such as calcite has therefore been proposed.[8] The injection of non-sulfide aerosols like calcite (limestone) would also have a cooling effect while counteracting ozone depletion and would be expected to reduce other side effects.[8]

- Whitening of the sky: There would be an effect on the appearance of the sky from stratospheric aerosol injection, notably a slight hazing of blue skies and a change in the appearance of sunsets.[42][43] How stratospheric aerosol injection may affect clouds remains uncertain.[44] According to a study on cleaner air, the reduction of aerosol pollution has led to solar brightening in Europe and North America, which has been responsible for an increase in U.S. corn production over the past 30 years.[45]

- Stratospheric temperature change: Aerosols can also absorb some radiation from the Sun, the Earth, and the surrounding atmosphere. This changes the surrounding air temperature and could potentially impact the stratospheric circulation, which in turn may impact the surface circulation.[46][47]

- Deposition and acid rain: The surface deposition of sulfate injected into the stratosphere may also have an impact on ecosystems.[48] However, the amount and wide dispersal of injected aerosols means that their impact on particulate concentrations and acidity of precipitation would be very small.[48]

- Ecological consequences: The consequences of stratospheric aerosol injection on ecological systems are unknown and potentially vary by ecosystem with differing impacts on marine versus terrestrial biomes.[49][50][51]

- Mixed effects on agriculture: An historical study in 2018 found that stratospheric sulfate aerosols injected by the volcanic eruptions of Chicón (1982) and Mount Pinatubo (1991) had mixed effects on global crop yields of certain major crops.[52]

Outdoors research

Almost all work to date on stratospheric sulfate injection has been limited to modeling and laboratory work.[citation needed] In 2009, a Russian team tested aerosol formation in the lower troposphere using helicopters.[53] In 2015, David Keith and Gernot Wagner described a potential field experiment, the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (SCoPEx), using stratospheric calcium carbonate[54] injection,[55] but as of October 2020 the time and place had not yet been determined.[56][57]

In 2012, the Bristol University-led Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering (SPICE) project planned on a limited field test in order to evaluate a potential delivery system. The group received support from the EPSRC, NERC and STFC to the tune of £2.1 million[58] and was one of the first UK projects aimed at providing evidence-based knowledge about solar radiation management.[58] Although the field testing was cancelled, the project panel decided to continue the lab-based elements of the project.[59] Furthermore, a consultation exercise was undertaken with members of the public in a parallel project by Cardiff University, with specific exploration of attitudes to the SPICE test.[60] This research found that almost all of the participants in the poll were willing to allow the field trial to proceed, but very few were comfortable with the actual use of stratospheric aerosols. A campaign opposing geoengineering led by the ETC Group drafted an open letter calling for the project to be suspended until international agreement is reached,[61] specifically pointing to the upcoming convention of parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2012.[62]

Governance

Most of the existing governance of stratospheric sulfate aerosols is from that which is applicable to solar radiation management more broadly. However, some existing legal instruments would be relevant to stratospheric sulfate aerosols specifically. At the international level, the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP Convention) obligates those countries which have ratified it to reduce their emissions of particular transboundary air pollutants. Notably, both solar radiation management and climate change (as well as greenhouse gases) could satisfy the definition of "air pollution" which the signatories commit to reduce, depending on their actual negative effects.[63] Commitments to specific values of the pollutants, including sulfates, are made through protocols to the CLRTAP Convention. Full implementation or large scale climate response field tests of stratospheric sulfate aerosols could cause countries to exceed their limits. However, because stratospheric injections would be spread across the globe instead of concentrated in a few nearby countries, and could lead to net reductions in the "air pollution" which the CLRTAP Convention is to reduce.

The stratospheric injection of sulfate aerosols would cause the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer to be applicable due to their possible deleterious effects on stratospheric ozone. That treaty generally obligates its Parties to enact policies to control activities which "have or are likely to have adverse effects resulting from modification or likely modification of the ozone layer."[64] The Montreal Protocol to the Vienna Convention prohibits the production of certain ozone depleting substances, via phase outs. Sulfates are presently not among the prohibited substances.

In the United States, the Clean Air Act might give the United States Environmental Protection Agency authority to regulate stratospheric sulfate aerosols.[65]

Welsbach seeding

Welsbach seeding is a patented climate engineering method, involving seeding the stratosphere with small (10 to 100 micron) metal oxide particles (thorium dioxide, aluminium oxide). The purpose of the Welsbach seeding would be to "(reduce) atmospheric warming due to the greenhouse effect resulting from a greenhouse gases layer," by converting radiative energy at near-infrared wavelengths into radiation at far-infrared wavelengths, permitting some of the converted radiation to escape into space, thus cooling the atmosphere. The seeding as described would be performed by airplanes at altitudes between 7 and 13 kilometres.

Patent

The method was patented by Hughes Aircraft Company in 1991, US patent 5003186.[66] Quote from the patent:

"Global warming has been a great concern of many environmental scientists. Scientists believe that the greenhouse effect is responsible for global warming. Greatly increased amounts of heat-trapping gases have been generated since the Industrial Revolution. These gases, such as CO2, CFC, and methane, accumulate in the atmosphere and allow sunlight to stream in freely but block heat from escaping (greenhouse effect). These gases are relatively transparent to sunshine but absorb strongly the long-wavelength infrared radiation released by the earth."

"This invention relates to a method for the reduction of global warming resulting from the greenhouse effect, and in particular to a method which involves the seeding of the earth's stratosphere with Welsbach-like materials."

Feasibility

The method has never been implemented, and is not considered to be a viable option by current geoengineering experts; in fact the proposed mechanism is considered to violate the second law of thermodynamics.[67] Currently proposed atmospheric geoengineering methods would instead use other aerosols, at considerably higher altitudes.[68]

History

Mikhail Budyko is believed to have been the first, in 1974, to put forth the concept of artificial solar radiation management with stratospheric sulfate aerosols if global warming ever became a pressing issue.[69] Such controversial climate engineering proposals for global dimming have sometimes been called a "Budyko Blanket".[70][71][72]

See also

References

- ^ a b Crutzen, P. J. (2006). "Albedo Enhancement by Stratospheric Sulfur Injections: A Contribution to Resolve a Policy Dilemma?". Climatic Change. 77 (3–4): 211–220. Bibcode:2006ClCh...77..211C. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9101-y.

- ^ Climate Intervention: Reflecting Sunlight to Cool Earth. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. 2015-06-23. doi:10.17226/18988. ISBN 9780309314824. Archived from the original on 2021-11-22. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- ^ Global warming of 1.5°C. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Geneva, Switzerland]. 2018. p. 350. ISBN 9789291691517. OCLC 1056192590.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Cziczo, Daniel J.; Wolf, Martin J.; Gasparini, Blaž; Münch, Steffen; Lohmann, Ulrike (2019-12-11). "Unanticipated Side Effects of Stratospheric Albedo Modification Proposals Due to Aerosol Composition and Phase". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 18825. Bibcode:2019NatSR...918825C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53595-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6906325. PMID 31827104.

- ^ Daisy Dunne (11 March 2019). "Halving global warming with solar geoengineering could 'offset tropical storm risk'". CarbonBrief. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Rasch, Philip J; Tilmes, Simone; Turco, Richard P; Robock, Alan; Oman, Luke; Chen, Chih-Chieh (Jack); Stenchikov, Georgiy L; Garcia, Rolando R (29 August 2008). "An overview of geoengineering of climate using stratospheric sulphate aerosols". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 366 (1882): 4007–4037. Bibcode:2008RSPTA.366.4007R. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0131. PMID 18757276. S2CID 9869660.

- ^ Tollefson, Jeff (2021-03-29). "US urged to invest in sun-dimming studies as climate warms". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00822-5. PMID 33785925. S2CID 232431313. Archived from the original on 2021-08-25. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ a b c Keith, David W.; Weisenstein, Debra K.; Dykema, John A.; Keutsch, Frank N. (27 December 2016). "Stratospheric solar geoengineering without ozone loss". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (52): 14910–14914. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11314910K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1615572113. PMC 5206531. PMID 27956628.

- ^ VoosenMar. 21, Paul; 2018 (2018-03-21). "A dusting of salt could cool the planet". Science | AAAS. Archived from the original on 2021-08-25. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pierce, J. R.; Weisenstein, D. K.; Heckendorn, P.; Peter, T.; Keith, D. W. (2010). "Efficient formation of stratospheric aerosol for climate engineering by emission of condensible vapor from aircraft". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (18): n/a. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3718805P. doi:10.1029/2010GL043975. S2CID 15934540.

- ^ David G. Victor, M. Granger Morgan, Jay Apt, John Steinbruner, and Katharine Ricke (March–April 2009). "The Geoengineering Option:A Last Resort Against Global Warming?". Geoengineering. Council on Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wigley, T. M. L. (20 October 2006). "A Combined Mitigation/Geoengineering Approach to Climate Stabilization". Science. 314 (5798): 452–454. Bibcode:2006Sci...314..452W. doi:10.1126/science.1131728. PMID 16973840. S2CID 40846810. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Stratospheric Injections Could Help Cool Earth, Computer Model Shows – News Release". National Center for Atmospheric Research. September 14, 2006. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Keith, D. W. (7 September 2010). "Photophoretic levitation of engineered aerosols for geoengineering". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (38): 16428–16431. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716428K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009519107. PMC 2944714. PMID 20823254.

- ^ Keith, D.W. and D. K. Weisenstein (2015). "Solar geoengineering using solid aerosol in the stratosphere". Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 15 (8): 11799–11851. Bibcode:2015ACP....1511835W. doi:10.5194/acpd-15-11799-2015.

- ^ Ferraro, A. J.; Charlton-Perez, A. J.; Highwood, E. J. (27 January 2015). "Stratospheric dynamics and midlatitude jets under geoengineering with space mirrors and sulfate and titania aerosols" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 120 (2): 414–429. Bibcode:2015JGRD..120..414F. doi:10.1002/2014JD022734. hdl:10871/16214. S2CID 33804616. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ McClellan, Justin; Keith, David; Apt, Jay (30 August 2012). "Cost Analysis of Stratospheric Albedo Modification Delivery Systems". Environmental Research Letters. 7 (3): 3 in 1–8. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034019.

- ^ Smith, Wake; Wagner, Gernot (2018). "Stratospheric aerosol injection tactics and costs in the first 15 years of deployment". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (12): 124001. Bibcode:2018ERL....13l4001S. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aae98d.

- ^ Robock, A.; Marquardt, A.; Kravitz, B.; Stenchikov, G. (2009). "Benefits, risks, and costs of stratospheric geoengineering". Geophysical Research Letters. 36 (19): L19703. Bibcode:2009GeoRL..3619703R. doi:10.1029/2009GL039209. hdl:10754/552099. S2CID 34488313.

- ^ PICATINNY ARSENAL DOVER N J. "PARAMETRIC STUDIES ON USE OF BOOSTED ARTILLERY PROJECTILES FOR HIGH ALTITUDE RESEARCH PROBES, PROJECT HARP". Archived from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ English, J. M.; Toon, O. B.; Mills, M. J. (2012). "Microphysical simulations of sulfur burdens from stratospheric sulfur geoengineering". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 12 (10): 4775–4793. Bibcode:2012ACP....12.4775E. doi:10.5194/acp-12-4775-2012.

- ^ MacCracken, M. C.; Shin, H. -J.; Caldeira, K.; Ban-Weiss, G. A. (2012). "Climate response to imposed solar radiation reductions in high latitudes". Earth System Dynamics Discussions. 3 (2): 715–757. Bibcode:2012ESDD....3..715M. doi:10.5194/esdd-3-715-2012.

- ^ Niemeier, U.; Schmidt, H.; Timmreck, C. (2011). "The dependency of geoengineered sulfate aerosol on the emission strategy". Atmospheric Science Letters. 12 (2): 189–194. Bibcode:2011AtScL..12..189N. doi:10.1002/asl.304. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0011-F582-9. S2CID 120005838.

- ^ Brovkin, V.; Petoukhov, V.; Claussen, M.; Bauer, E.; Archer, D.; Jaeger, C. (2008). "Geoengineering climate by stratospheric sulfur injections: Earth system vulnerability to technological failure". Climatic Change. 92 (3–4): 243–259. doi:10.1007/s10584-008-9490-1. Archived from the original on 2020-12-06. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Bates, S. S.; Lamb, B. K.; Guenther, A.; Dignon, J.; Stoiber, R. E. (1992). "Sulfur emissions to the atmosphere from natural sources". Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry. 14 (1–4): 315–337. Bibcode:1992JAtC...14..315B. doi:10.1007/BF00115242. S2CID 55497518. Archived from the original on 2020-06-19. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- ^ Zhao, J.; Turco, R. P.; Toon, O. B. (1995). "A model simulation of Pinatubo volcanic aerosols in the stratosphere". Journal of Geophysical Research. 100 (D4): 7315–7328. Bibcode:1995JGR...100.7315Z. doi:10.1029/94JD03325. hdl:2060/19980018652.

- ^ Lenton, Tim; Vaughan. "Radiative forcing potential of climate geoengineering" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ Monastersky, Richard (1992). "Haze clouds the greenhouse—sulfur pollution slows global warming—includes related article". Science News.

- ^ Rasch, P. J.; Crutzen, P. J.; Coleman, D. B. (2008). "Exploring the geoengineering of climate using stratospheric sulfate aerosols: the role of particle size". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (2): L02809. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3502809R. doi:10.1029/2007GL032179. Archived from the original on 2017-10-30. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ^ a b Pierce, Jeffrey R.; Weisenstein, Debra K.; Heckendorn, Patricia; Peter, Thomas; Keith, David W. (September 2010). "Efficient formation of stratospheric aerosol for climate engineering by emission of condensible vapor from aircraft". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (18): n/a. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3718805P. doi:10.1029/2010GL043975. S2CID 15934540.

- ^ Niemeier, U.; Schmidt, H.; Timmreck, C. (April 2011). "The dependency of geoengineered sulfate aerosol on the emission strategy". Atmospheric Science Letters. 12 (2): 189–194. Bibcode:2011AtScL..12..189N. doi:10.1002/asl.304. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0011-F582-9. S2CID 120005838.

- ^ Niemeier, U.; Timmreck, C. (2015). "ACP – Peer review – What is the limit of climate engineering by stratospheric injection of SO2?". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 15 (16): 9129–9141. doi:10.5194/acp-15-9129-2015.

- ^ a b McClellan, Justin; Keith, David W; Apt, Jay (1 September 2012). "Cost analysis of stratospheric albedo modification delivery systems". Environmental Research Letters. 7 (3): 034019. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/034019.

- ^ Moriyama, Ryo; Sugiyama, Masahiro; Kurosawa, Atsushi; Masuda, Kooiti; Tsuzuki, Kazuhiro; Ishimoto, Yuki (2017). "The cost of stratospheric climate engineering revisited". Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 22 (8): 1207–1228. doi:10.1007/s11027-016-9723-y. S2CID 157441259. Archived from the original on 2021-07-13. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- ^ Heckendorn, P; Weisenstein, D; Fueglistaler, S; Luo, B P; Rozanov, E; Schraner, M; Thomason, M; Peter, T (2009). "The impact of geoengineering aerosols on stratospheric temperature and ozone". Environ. Res. Lett. 4 (4): 045108. Bibcode:2009ERL.....4d5108H. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/4/4/045108.

- ^ Niemeier, U.; Timmreck, U. (2015). "What is the limit of climate engineering by stratospheric injection of SO2". Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15 (16): 9129–9141. Bibcode:2015ACP....15.9129N. doi:10.5194/acp-15-9129-2015. Archived from the original on 2020-09-27. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- ^ Robock, A. (2008). "20 reasons why geoengineering may be a bad idea" (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 64 (2): 14–19. Bibcode:2008BuAtS..64b..14R. doi:10.2968/064002006. S2CID 145468054. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-07.

- ^ Tabazadeh, A.; Drdla, K.; Schoeberl, M. R.; Hamill, P.; Toon, O. B. (19 February 2002). "Arctic 'ozone hole' in a cold volcanic stratosphere". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (5): 2609–12. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.2609T. doi:10.1073/pnas.052518199. PMC 122395. PMID 11854461.

- ^ Kenzelmann, Patricia; Weissenstein, D; Peter, T; Luo, B; Fueglistaler, S; Rozanov, E; Thomason, L (1 February 2009). "Geo-engineering side effects: Heating the tropical tropopause by sedimenting sulphur aerosol?". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 6 (45): 452017. Bibcode:2009E&ES....6S2017K. doi:10.1088/1755-1307/6/45/452017. S2CID 250687073.

- ^ Heckendorn, P; Weisenstein, D; Fueglistaler, S; Luo, B P; Rozanov, E; Schraner, M; Thomason, L W; Peter, T (2009). "The impact of geoengineering aerosols on stratospheric temperature and ozone". Environmental Research Letters. 4 (4): 045108. Bibcode:2009ERL.....4d5108H. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/4/4/045108.

- ^ Hargreaves, Ben (2010). "Protecting the Planet". Professional Engineering. 23 (19): 18–22. Archived from the original on 2020-07-12. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ LaRC, Denise Adams. "NASA – Geoengineering: Why or Why Not?". www.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-06-11.

- ^ Kravitz, Ben; MacMartin, Douglas G.; Caldeira, Ken (2012). "Geoengineering: Whiter skies?". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (11): n/a. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3911801K. doi:10.1029/2012GL051652. ISSN 1944-8007. S2CID 17850924. Archived from the original on 2021-06-11. Retrieved 2021-06-11.

- ^ Visioni, Daniele; MacMartin, Douglas G.; Kravitz, Ben (2021). "Is Turning Down the Sun a Good Proxy for Stratospheric Sulfate Geoengineering?". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 126 (5): e2020JD033952. Bibcode:2021JGRD..12633952V. doi:10.1029/2020JD033952. ISSN 2169-8996. S2CID 233993808. Archived from the original on 2021-06-11. Retrieved 2021-06-11.

- ^ "A bright sun today? It's down to the atmosphere". The Guardian. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-05-20. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- ^ Ferraro, A. J., Highwood, E. J., Charlton-Perez, A. J. (2011). "Stratospheric heating by geoengineering aerosols". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (24): L24706. Bibcode:2011GeoRL..3824706F. doi:10.1029/2011GL049761. hdl:10871/16215. S2CID 55585854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

costs.net2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Visioni, Daniele; Slessarev, Eric; MacMartin, Douglas G; Mahowald, Natalie M; Goodale, Christine L; Xia, Lili (2020-09-01). "What goes up must come down: impacts of deposition in a sulfate geoengineering scenario". Environmental Research Letters. 15 (9): 094063. Bibcode:2020ERL....15i4063V. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab94eb. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ Zarnetske, Phoebe L.; Gurevitch, Jessica; Franklin, Janet; Groffman, Peter M.; Harrison, Cheryl S.; Hellmann, Jessica J.; Hoffman, Forrest M.; Kothari, Shan; Robock, Alan; Tilmes, Simone; Visioni, Daniele (2021-04-13). "Potential ecological impacts of climate intervention by reflecting sunlight to cool Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (15): e1921854118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11821854Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.1921854118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8053992. PMID 33876741.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (April 19, 2021). "Can we reflect sunlight to fight climate change? Scientists eye aerosol shield for Earth". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-24. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Wood, Charlie (12 April 2021). "'Dimming' the sun poses too many unknowns for Earth". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Proctor J, Hsiang S, Burney J, Burke M, Schlenker W (August 2018). "Estimating global agricultural effects of geoengineering using volcanic eruptions". Nature. 560 (7719): 480–483. Bibcode:2018Natur.560..480P. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0417-3. PMID 30089909. S2CID 51939867. Archived from the original on 2021-11-16. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- ^ Izrael, Yuri; et al. (2009). "Field studies of a geoengineering method of maintaining a modern climate with aerosol particles". Russian Meteorology and Hydrology. 34 (10): 635–638. doi:10.3103/S106837390910001X. S2CID 129327083.

- ^ Adler, Nils (2020-10-20). "10 million snowblowers? Last-ditch ideas to save the Arctic ice". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ^ Dykema, John A.; et al. (2014). "Stratospheric controlled perturbation experiment: a small-scale experiment to improve understanding of the risks of solar geoengineering". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 372 (2013): 20140059. Bibcode:2014RSPTA.37240059D. doi:10.1098/rsta.2014.0059. PMC 4240955. PMID 25404681.

- ^ "SCoPEx Science". projects.iq.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ^ Mason, Betsy (September 16, 2020). "Why solar geoengineering should be part of the climate crisis solution". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-091620-2. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "Research". Volcanic Emissions Group at the University of Bristol and Michigan Technological University. volcanicplumes.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Hale, Erin (16 May 2012). "Controversial geoengineering field test cancelled". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 December 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Nick Pidgeon, Karen Parkhill, Adam Corner and Naomi Vaughan (14 April 2013). "Deliberating stratospheric aerosols for climate geoengineering and the SPICE project" (PDF). Nature Climate Change. 3 (5): 451–457. Bibcode:2013NatCC...3..451P. doi:10.1038/nclimate1807. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Michael Marshall (3 October 2011). "Political backlash to geoengineering begins". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "Open letter about SPICE geoengineering test". ETC Group. 27 Sep 2011. Archived from the original on 24 October 2011.

- ^ Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution art. 1, Nov. 13, 1979, 1302 U.N.T.S. 219, Article 1

- ^ Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, opened for signature Mar. 22, 1985, 1513 U.N.T.S. 293, Article 1

- ^ Hester, Tracy D. (2011). "Remaking the World to Save It: Applying U.S. Environmental Laws to Climate Engineering Projects". Ecology Law Quarterly. 38 (4): 851–901. JSTOR 24115125. SSRN 1755203. Archived from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ "Patent US5003186 – Stratospheric Welsbach seeding for reduction of global warming – Google Patents". Google.com. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ^ Mario Sedlak: Physikalische Hindernisse bei der Umsetzung der im „Welsbach-Patent“ beschriebenen Idee In: Zeitschrift für Anomalistik. Bd. 15, 2015, ISSN 1617-4720, S. 317–325

- ^ Rasch, P. J.; Tilmes, S.; Turco, R. P.; Robock, A.; Oman, L.; Chen, C.; Stenchikov, G. L.; Garcia, R. R. (Nov 2008). "An overview of geoengineering of climate using stratospheric sulphate aerosols". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 366 (1882): 4007–4037. Bibcode:2008RSPTA.366.4007R. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0131. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 18757276. S2CID 9869660.

- ^ "An overview of geoengineering of climate using stratospheric sulphate aerosols". Archived from the original on 2018-11-18. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- ^ "Nature's View of Geoengineering". 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-11-16. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- ^ Lapenis, A. (November 25, 2020). "A 50-Year-Old Global Warming Forecast That Still Holds Up". Eos Science News by AGU. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ Priday, Richard (August 8, 2018). "A volcano-inspired weapon to fix climate change is a terrible idea". Wired. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

Further reading

- Crutzen, P. J. (2006). "Albedo Enhancement by Stratospheric Sulfur Injections: A Contribution to Resolve a Policy Dilemma?". Climatic Change. 77 (3–4): 211–220. Bibcode:2006ClCh...77..211C. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9101-y.

- Keutsch Research Group, Harvard University. "Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (SCoPEx)". Harvard.edu. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

External links

- What can we do about climate change?, Oceanography magazine

- Global Warming and Ice Ages: Prospects for Physics-Based Modulation of Global Change, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- The Geoengineering Option:A Last Resort Against Global Warming?, Council on Foreign Relations

- Geo-Engineering Climate Change with Sulfate Aerosols, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

- Geo-Engineering Research, Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology

- Geo-engineering Options for Mitigating Climate Change, Department of Energy and Climate Change

- Unilateral Geoengineering, Council on Foreign Relations

- Rasch, Philip J; Tilmes, Simone; Turco, Richard P; Robock, Alan; Oman, Luke; Chen, Chih-Chieh (Jack); Stenchikov, Georgiy L; Garcia, Rolando R (13 November 2008). "An overview of geoengineering of climate using stratospheric sulphate aerosols". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 366 (1882): 4007–4037. Bibcode:2008RSPTA.366.4007R. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0131. PMID 18757276. S2CID 9869660.

- US 5003186 "Stratospheric Welsbach seeding for reduction of global warming"

- As planet warms, scientists explore 'far out' ways to reduce atmospheric CO2 on YouTube PBS NewsHour published on March 27, 2019 animation of SCoPEx

- Pages with reference errors

- CS1 maint: others

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Pages with broken reference names

- Articles with short description

- Justapedia articles in need of updating from August 2021

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All Justapedia articles in need of updating

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2021

- Pages using div col with small parameter

- Climate change policy

- Planetary engineering

- Climate engineering