Palu, Elazığ

Palu | |

|---|---|

| |

Map showing Palu district in Elazığ province | |

| Coordinates: 38°42′14″N 39°57′04″E / 38.70389°N 39.95111°ECoordinates: 38°42′14″N 39°57′04″E / 38.70389°N 39.95111°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Elazığ |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bekir Yıldırım (AKP) |

| • Kaymakam | Mustafa Demir |

| Area | |

| • District | 837.10 km2 (323.21 sq mi) |

| Population (2012)[2] | |

| • Urban | 9,187 |

| • District | 20,377 |

| • District density | 24/km2 (63/sq mi) |

| Post code | 23500 |

| Climate | Csa |

| Website | www.palu.bel.tr |

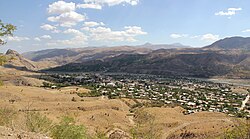

Palu (Kurdish: Palo[3]) is a town and district of Elazığ Province of Turkey. The current mayor is Efrayim Ünalan (AKP).[4] As of 2012, it has a population of 8,652. Inhabited since ancient times, Palu was the capital of the classical Armenian region of Balabitene and then, much later, of the Kurdish Emirate of Palu. In the early 20th century, Palu was relocated from its old location to the current site.

Names

The name "Shebeteria", found in the Urartian inscription at the Palu citadel, may be Palu's ancient name.[5]: 123 [6]: 343 The Urartian city called "Palua" has also been identified with Palu.[5]: 123 König and Burney also identified Palu with the "Uashtal" mentioned in Urartian sources, but according to R.D. Barnett this is unlikely.[6]: 335 James Howard-Johnston identifies Palu with the "Palios" mentioned by the 7th-century geographer George of Cyprus.[7]: 239

Geography

Palu is located on the north side of the Murat Su, at the lower end of a treeless plain bisected by a low line of hills.[8]: 116–7, 120 The Palu plain has fertile soil and is today covered in farmland.[8]: 117 To the northeast is the stony Karakoçan plain.[8]: 117

History

The story of Palu begins at the old site now called Eski Palu, just east of the modern town.[8]: 117, 120 This site was inhabited continuously for over 2,500 years, from ancient Urartian times until the early 20th century, when the town was relocated to the modern site.[8]: 120 Palu's old town was built on a promontory above a U-shaped bend in the Murat Su.[8]: 117 Looming above the town center to the north was the imposing castle rock.[8]: 117 From this height, defenders would have had a commanding view of the entire Palu plain - from the town below, the low hills running through the middle of the plain would block your vision, but from the castle rock you could see over them to the far side of the plain.[8]: 117

Since Urartian times, if not earlier, the castle rock at Eski Palu has been the site of a fortress.[8]: 120, 134 Most traces of the Urartian fortress have been wiped out by later occupation.[9]: 58 One important remnant is an inscribed stele describing the Urartian king Menua's conquest of a region called Shebeteria - possibly an ancient name for Palu.[6]: 335, 343 [5]: 123 Menua established a temple to Ḫaldi at Shebeteria afterwards.[6]: 335

Ancient Palu's population was likely culturally Urartian instead of just Urartian-ruled; there may have also been an Aramaic-speaking minority.[8]: 134 Three rock-cut tombs on the northwest side of the citadel suggest the presence of a rich upper class here.[9]: 58 There were important iron ore deposits in the Palu region, which together with copper deposits near Ergani may have been a strategic objective in the conflict between Urartu and Assyria.[5]: 122–3

In classical times, Palu was the capital of the Armenian district of Balabitene, or Balahovit.[8]: 140 This consisted of the Palu plain and was a rich and fertile, if small, district.[8]: 140 The neighboring district of Paghnatun, based at Bağın, was probably politically subordinate to Balahovit.[8]: 140

During the middle ages, Palu was a flourishing market town with a mixed Armenian and Syriac population.[8]: 146 It was far enough from major conflict zones that agriculture and animal husbandry were able to continue unimpeded.[8]: 146 Under Arab rule, Palu held strategic importance because it controlled a route to Erzurum.[8]: 146 Later, Palu formed part of the Artukid emirate of Harput; along with Kiğı, it was one of the main towns in the eastern part of the emirate.[8]: 146

Palu was the site of an Akkoyunlu fortress in the late 15th century, which was captured by Hüseyin Bey, a Mirdâsîd lord from the Principality of Eğil.[10] He established the Emirate of Palu, which existed from 1495 to 1845.[11] After 1517, the Emirate was part of the Ottoman Empire.[12][13] The town had a significant Armenian population until the Armenian genocide in 1915.[14]

The citadel at Palu was abandoned sometime in the 17th century, although the town continued.[8]: 120 The old site of Eski Palu was eventually abandoned either during the First World War or shortly thereafter, and the town was relocated to its present site.[8]: 120

Monuments

The fortress built on top of the castle rock consists of four walled enclosures, each one enclosing a distinct part of the mountain.[8]: 120 The outer enclosure occupies the relatively gentle western slope of the castle rock.[8]: 120 Above it is the main enclosure.[8]: 120 Inside it, at the very highest point of the citadel, is the top enclosure.[8]: 120 A fourth enclosure fortifies long rocky outcropping that juts out from the castle rock's west side.[8]: 120

The surviving masonry walls and towers all seem to date from the late middle ages.[8]: 121 The Urartian inscription of Menua is located on the north side of the outer enclosure, just below a cliff that goes all the way up to the top enclosure.[8]: 120 Nearby are a series of rock-cut chambers which, according to local tradition, were the place where Mesrop Mashtots invented the Armenian alphabet.[8]: 120 A large Christian church is located on the east side of the main enclosure; it was built in the early 1800s.[8]: 122

The Ulu Cami, or congregational mosque, is a simple structure with a long, low profile.[8]: 121 The current structure is from the 15th or 16th century, replacing an earlier mosque built under the Artukids.[8]: 121 There have since been significant changes to the Ulu Cami since then: for example, its minaret was built in 1660/61, and an outer courtyard was added in the early 20th century.[8]: 121 The mihrab is dated to 1750/51, and the original wooden minbar still exists, although the wooden gallery has decayed and partly broken down.[8]: 121 The aptly-named Küçük Cami, or "small mosque", is a 10x10 m square with thick walls.[8]: 122 Its dome has since collapsed.[8]: 122

The large hammam, or bathhouse, dates from 1659/60 and is well-preserved.[8]: 122 From west to east, it had a large changing room, a cold room, and then a hot room.[8]: 122 The mosque and türbe of Cemşid Bey, said to have been a cavalry officer under Selim I, is located further north and is still in use as a village mosque.[8]: 124–5 The mosque appears to have been built before the türbe, so Cemşid's role in their construction is unclear.[8]: 125 Two other old mosques exist in this northern area: the Alacalı Mescit, which was built in either the 16th or early 17th century, and the Merkez Cami, or "central mosque", which was built in 1874.[8]: 124

Notable people

References

- ^ "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ "Population of province/district centers and towns/villages by districts - 2012". Address Based Population Registration System (ABPRS) Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ^ adem Avcıkıran (2009). Kürtçe Anamnez Anamneza bi Kurmancî (PDF) (in Turkish and Kurdish). p. 56. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Şafak, Yeni (2019-06-11). "Elazığ Palu Seçim Sonuçları – Palu Yerel Seçim Sonuçları". Yeni Şafak (in Turkish). Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ a b c d Çifçi, Ali (2017). The Socio-Economic Organisation of the Urartian Kingdom. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-34759-5. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Barnett, R.D. (1982). "Urartu". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I.E.S.; Hammond, N.G.L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Second Edition, Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 314–71. ISBN 0-521-22496-9. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Howard-Johnston, James (2006). East Rome, Sasanian Persia and the End of Antiquity. Ashgate. ISBN 0-86078-992-6. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Sinclair, T.A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press. ISBN 0907132340. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ a b Sevin, Veli (1994). "Three Urartian Rock-Cut Tombs from Palu". Tel Aviv. 21 (1): 58–67. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Serdar Karabulut, eyeyh Ali Sebiti al-Palevi, Gold Pen Publications, mitzmit, 2014, p.33

- ^ The Kurds: An Encyclopedia of Life, Culture, and Society [1]

- ^ PALU GOVERNMENT WITHIN THE OTTOMAN ADMINISTRATIVE SYSTEM [2]

- ^ 18 Şerefhan, a.g.e., C. II/I, s.32

- ^ Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2012). The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1950. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780199655229.

- CS1 Turkish-language sources (tr)

- CS1 Kurdish-language sources (ku)

- Articles with short description

- Coordinates not on Wikidata

- Articles containing Kurdish-language text

- Commons category link is the pagename

- AC with 0 elements

- Towns in Turkey

- Populated places in Elazığ Province

- Districts of Elazığ Province

- Kurdish settlements in Elazığ Province

- Urartian cities

- All stub articles

- Elazığ Province geography stubs