Ottoman Bank

The Ottoman Bank (Turkish: Osmanlı Bankası), known from 1863 to 1925 as the Imperial Ottoman Bank (French: Banque Impériale Ottomane, Ottoman Turkish: بانق عثمانی شاهانه[3]) and correspondingly referred to by its French acronym BIO, was a bank that played a major role in the financial history of the Ottoman Empire. By the early 20th century, it was the dominant bank in the Ottoman Empire, and one of the largest in the world.[4]: 590

It was founded in 1856 as a British institution chartered in London, and reorganized in 1863 as a French-British venture with head office in Constantinople, on a principle of strict equality between British and French stakeholders. It soon became dominated by French interests, however, primarily because of the greater success of its offerings among French savers than British ones. In its early years, the BIO was principally a lender to the Ottoman government with a monopoly on banknote issuance and other public-interest roles, including all treasury operations of the Ottoman state under a 1874 agreement that was however never fully implemented. In the 1890s, it pivoted to a greater emphasis on commercial banking, which it developed with lasting success despite a serious crisis in 1895.

Following World War I, the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, later known as Paribas, took control of the BIO, and renamed it Ottoman Bank in 1925. The bank's remaining public-interest privileges and monopolies were phased out. Its operations outside Turkey were gradually dismantled, a process that was completed in 1975. The Ottoman Bank became Turkish-owned when Garanti Bank purchased it from Paribas in 1996, and was eventually subsumed in 2001 into the Garanti Bank operations and corporate identity, in turn rebranded Garanti BBVA in 2019.

Name

Between 1863 and 1925 the bank was generally referred to using its French name, banque impériale ottomane (BIO), even in English-speaking contexts. This was because French was the international language of the era and especially prominent in the business community among the many languages of the Ottoman Empire.[5] In Turkey after 1925, the bank increasingly operated under its Turkish name Osmanlı Bankası.

History

Background

The Ottoman Empire had traditionally relied on credit from individual financiers known as sarraf, which included Muslims but also Armenians, Greeks, and Jews, as well as traders of European descent. In the early 19th century, prominent sarraf families had coalesced into a community mainly based in the Galata neighborhood of Constantinople, known as the "Galata bankers" which operated as family businesses. The first formal banking establishment that was not strictly family-controlled was a joint venture between the Ottoman state and two prominent Galata bankers, Jacques Alléon and Theodore Baltazzi, which took the name of Banque de Constantinople in 1847 but was wound up in 1852. Another project, proposed as the Banque Nationale de Turquie by French entrepreneur Ariste Jacques Trouvé-Chauvel, was considered by the Ottoman government in 1853 but not implemented.[6]

During the Crimean War that started in October 1853, France and Great Britain were allied in support of the Ottoman Empire. In 1855, the two nations sent a joint mission to assess Ottoman finances, led by Alexandre de Plœuc for France and Augustus Edward Hobart-Hampden for the UK, who would later become respectively the first and second General Managers of the Imperial Ottoman Bank in Constantinople.[6]

The first Ottoman Bank (1856-1863)

In early 1856, Sultan Abdulmejid I called for modern banks to be created in the Empire to improve its financial system and foster economic development. Three main projects emerged in response, respectively promoted by the Rothschild family (in London, Paris and Vienna), the Pereire brothers (in Paris), and a group of British financiers around Austen Henry Layard and the private bank Glyn, Mills & Co. The Ottoman government opted for the latter, which it identified as better preserving the country's independence from western financiers in comparison with the assertive approaches of the Rothschilds and Pereires.[6] The British project was initially conceived by two businessmen, Peter Pasquali et Stephen Sleight, who had participated earlier in 1856 in the creation of the Bank of Egypt, the first Egyptian joint-stock bank.[7] The project benefited from the support of such influential diplomats as George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon and Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe, in contrast to the Pereire initiative that was not much supported by French ambassador Édouard Thouvenel. As was customary at the time for an enterprise that would operate abroad, the British authorities sought approval from the Ottoman government, and once that was confirmed in April 1856, the bank was chartered on 24 May 1856 as an English entity with seat at 26, Old Broad Street in London. The group of financiers that supported it also included Thomas Charles Bruce, William Richard Drake, Pascoe Du Pré Grenfell, Lachlan Mackintosh Rate, and John Stewart.[6]

The Ottoman Bank then sought an issuance privilege from the Ottoman government, but the latter temporized as he preferred a solution that would combine British and French stakeholders, mirroring the Crimean War coalition. As high-ranking official Mehmed Fuad Pasha put it in May 1856 to French Ambassador Thouvenel, the Sublime Porte's wish "was to perpetuate as much as possible the spirit of alliance that saved Turkey during the war, namely providing equal shares to French and English interests."[6] Even as the Ottoman Bank started its operations and opened its first branches, Layard soon understood that a different scheme would be needed to secure the issuance privilege. In a communication to Grand Vizier Mustafa Reşid Pasha in December 1856, he outlined what would eventually be the concept of the still-to-come BIO: a head office in Constantinople, but governance by two parallel committees in London and Paris that would be accountable to the British and French shareholders. Contrary to the desires of the Ottoman authorities, however, Layard insisted that they should not control the bank's management, only conceding a "supervisor" role for a high-ranking Ottoman official. In contrast to Layard, a competing British investor group led by Joseph Paxton presented a project to establish a "Bank of Turkey" with a Governor and Vice Governor who would be both appointed by the Sublime Porte. Paxton's project was endorsed by the Ottoman government in March 1857, but failed to raise investor interest in London as Layard had anticipated. A follow-up effort by some of Paxton's associates under the same name of "Bank of Turkey" started operations in 1858, but had to be placed into liquidation in 1861.[8]

Without the issuance privilege, the Ottoman Bank had modest beginnings with six staff in Constantinople (12 in 1858) and four in Smyrna. It made some poor credit allocation decisions, also suffered from the 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and a financial crisis in 1861, and met hostility from the Galata bankers.[6]

Foundation of the Imperial Ottoman Bank

By early 1862, circumstances favored the reconsideration of the Ottoman Bank project. Foreign investors had grown more confident about the reforming intent of the Porte. Mehmed Fuad Pasha had become Grand Vizier and was eager to see a bank emerge with an effective banknote issuance capacity. In line with the insistent position of France's ambassador, he made clear that British-French equality of participation would remain a necessary condition for granting the issuance privilege. In response, the Ottoman bank reached out to the Pereire brothers and their Crédit Mobilier, who assembled a group of distinguished French investors. On 16 November 1862 in Paris, the British and French negotiators reached an agreement that foresaw the winding up of the Ottoman Bank and transfer of its business to a newly created institution. Negotiations in Constantinople followed in December 1862 between a group of British and French representatives, supported by the two countries' embassies, and the Ottoman authorities. As Layard had suspected in late 1856, and in spite of the replacement of Fuad by Yusuf Kamil Pasha as Grand Vizier, the compromise that was found on the new bank's governance stipulated that its formal head office, board of directors and general manager would be located in Constantinople, but that the latter would be a foreign national and ultimately report to the committees to be formed in London and Paris. The Porte would only appoint a Commissioner with limited powers of oversight. The issuance privilege would be initially granted for a duration of thirty years, and came with a full tax exemption.[8] The bank would execute all financial operations of the Ottoman Treasury in Constantinople, and would be the government's financial agent both domestically and abroad. The bank would thus provide services of a central bank while also operating as a commercial operation.[9]

These arrangements were enshrined in a concession agreement which Kamil signed on 27 January 1863 together with Fuad, foreign minister Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha, finance minister Mustafa Fazıl Pasha, and chief auditor Ahmed Vefik Pasha. On 4 February 1863, the agreement was ratified by firman of Sultan Abdulaziz. On 5 March 1863, the Ottoman government registered the new Imperial Ottoman Bank which could then start its operations. That same day in London, the shareholders of the English-chartered Ottoman Bank voted to liquidate it in accordance with the November 1862 agreement, a process that was only finalized in June 1865. Meanwhile, the transfer of the old bank's operations in Constantinople to the new one had been completed on 1 June 1863.[8]

The governance concept of the BIO was unique and unprecedented. The two committees in London and Paris were not expected to meet jointly; instead, decisions by one committee became effective once ratified by the other committee. The annual general meetings of its shareholders were held in London.[2] The original committees included: in London, Sir William Clay (chair), James Alexander, John Anderson, Thomas Charles Bruce, George T. Clark, William Richard Drake, Pascoe St Leger Grenfell, Augustus Edward Hobart-Hampden, John W. Larking, Lachlan Mackintosh Rate, and John Stewart; and in Paris, Charles Mallet (chair), A. André, Vincent Buffarini, Raffaele de Ferrari, Achille Fould, Frédéric Greininger, Jean–Henri Hottinguer, the Pereire brothers, Alexis Pillet-Will, Casimir Salvador, and Antoine Jacob Stern.[10]: 402 Alexandre de Plœuc became the first general manager in Constantinople, with Edward Gilbertson as his deputy and the local board being otherwise composed of John Stewart, representing the London and Paris committees, and local bankers Antoine Alléon and Charles Simpson Hanson.[8]

Early activity as quasi-state bank

The early activity of the BIO was mostly about providing financing to the Ottoman government, even though as early as August 1865 the bank's staff was concerned about the creditworthiness of its main debtor, and the BIO was by no means the only player on that market.[11]

The BIO was not entirely oblivious of the broader financing needs of the Ottoman economy, however. As a complement to its own activity of lending to the Imperial government and international financial transactions, it sponsored in 1864 the creation of a separate bank that would focus on lending to local businessmen and local government.[10]: 42 That "younger sister", named the Société Générale de l'Empire Ottoman (SGEO, "General Company of the Ottoman Empire"), had as initial shareholders the BIO itself together with a number of Galata bankers such as Aristide Baltazzi, the Camondo family bank, Boghos Mısırlıoğlu, the Zafiropoulo & Zafiri partnership, and Christakis Zografos, as well as international partners: Bischoffheim & Goldschmidt; Frühling & Göschen; the Paris-based Oppenheim, Alberti et Cie; Augustus Ralli; Stern Brothers; and Siegmund Sulzbach.[10]: 403 After a few years, however, the relations within that group deteriorated, and by the 1870s the BIO had cut most of its exposure to the SGEO,[11] which was eventually liquidated at the expiration of its initial 30-year term in 1893,[12] at the time when the BIO was starting to develop its own commercial and retail banking operations throughout the Empire.[4]

Also in 1864, the BIO opened a branch in Salonica, the main Ottoman port city where it was not already present, and in the Cypriot port city of Larnaca. In November 1865, however, the shareholders rejected plans for more ambitious branch network expansion. In 1866, political developments in the newly formed United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia led the BIO to transform its two branches there, in Galaţi (est. 1856) and Bucharest (est. 1861) to a local subsidiary, the Bank of Romania, while their bad assets were retained by the BIO and eventually liquidated by 1872. In October 1867, the BIO opened a branch in Alexandria, its first in the Khedivate of Egypt. In 1868, a commercial branch was opened in Paris, first at 30, boulevard Haussmann; in 1870 it moved to the prestigious address of 7, rue Meyerbeer, facing the Palais Garnier, where it would remain for more than a century.[11]

In 1868, the Ottoman Bank faced its first serious competitor with the creation of Crédit Général Ottoman, a rival institution sponsored by France's Société Générale and several Galata bankers including the Tubini family but also Christakis Zografos and Stefanos Zafiropoulo, who had been the BIO's partners in the SGEO venture.[10]: 95–97 The Crédit Général Ottoman was a major underwriter of Ottoman treasury bonds, but ceased to operate in 1899.[12] Two other competitors were sponsored soon afterwards by Austria-Hungary, namely the Austro-Ottoman Bank (French: Banque austro-ottomane) in 1871 and the Austro-Turkish Bank (French: Banque austro-turque, sometimes Société de crédit austro-turque) in 1872,[11] but neither survived the crisis of the mid-1870s.[13]

On February 18, 1875, the BIO was authorized to control the budget, the expenditures and incomes of the Ottoman state, to ensure reform and control the precarious Ottoman financial situation. The character of the Ottoman Bank as a state bank was fully reaffirmed by extending its right of issue for 20 years and conferring on it the role of Treasurer of the Empire.

Commercial and investment banking development

The bank continued to help the Ottoman state through providing it several credits after the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), became a member of the Council of the Public Debt, and assumed the tobacco monopoly in a limited company. Following the re-establishment of the Empire's credit standing, the placing of Turkish loans abroad became possible around 1886. Enabled by the reduction of commitments towards the Treasury around 1890, following the improvement of public finances, the Ottoman Bank undertook a double activity of financing the Turkish economy and promoting other business.

Within the frame of merchant banking activities, it was mainly involved with public works and railways, the Beirut Port, the railway line Beirut-Damascus and its later extension to Homs, Hamah and Aleppo. The Bank's financial support continued to some other railway projects including the line Constantinople–Salonica, Smyrna–Kasaba (1892) and the Baghdad railway (1903). In 1896, the Bank played a major role in the establishment of the Ereğli coal mining company on the Black Sea shore. In August 1896, the bank was the subject of a seizure by Armenian Revolutionaries intent on bringing international attention to mistreatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.

World War I

The declaration of World War I damaged the Bank, since it lost credibility with the Ottoman government because of its British and French shareholders, and on the other hand the British and French governments considered the bank as an institution belonging to the enemy. This caused particular problems in Cyprus, an Ottoman province administered by Britain up until the First World War, when the island was annexed in response to the Turks siding with the Central Powers. After an initial run on the bank in 1914 left the local operation of the bank with less than £4,000 sterling in its vaults, and no means of replenishing its reserves from the head office in Constantinople, the bank was briefly closed by the British authorities and then allowed to re-open effectively as a separate semi-state company. In part this compromise seems to have been reached as the British authorities in Cyprus had themselves deposited their entire funds in the bank in Cyprus, some £40,000 sterling, which would have been lost had the bank been forced to close.[14] But, with the exception of Cyprus, during this time, the British and French executives of the bank left their posts, and the Ottoman Government abolished the privilege of issuing banknotes. However, its other activities continued.

Republic of Turkey

The Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas (BPPB) became a significant shareholder of the BIO and remained its controlling shareholder for decades,[15] with nearly half of the total equity capital (the rest being dispersed among many shareholders) as of 1991.[16]

Following its victory of the Turkish War of Independence, the Republic of Turkey signed a convention with the BIO on 10 March 1924, after which the bank's name was changed back to Ottoman Bank in May 1925. Even so, it was the only institution allowed to keep the word "Ottoman" in its name.[17] Under the new convention, the bank's role as a state bank was extended on a temporary basis given the Turkish government's intention to establish the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, which was only realized in 1931. Two other conventions, respectively in 1933 and 1952, led to the full normalization of the Ottoman Bank's status as a commercial bank.[18]

Under the direction of the BPPB, the Ottoman Bank kept its dual British-French structure, but with a new organizational concept in which individual countries where the bank had operations were allocated to one or the other of the two committees. Specifically, the Turkish bank itself and its subsidiaries in Syria / Lebanon and Serbia / Yugoslavia remained under the Paris Committee, whereas the London Committee managed the existing network in Cyprus and Egypt, and led new developments in Jordan (1925), Sudan (1949), Qatar (1956), Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rhodesia (1958), Abu Dhabi (1962), and Oman (1969).[18] Increasingly, this resulted in a bifurcation of the Ottoman Bank into two mutually autonomous groups.

The French group was gradually reduced to the Turkish operations of the Ottoman Bank. The Banque Franco-Serbe was nationalized by Yugoslavia in 1939. The Banque de Syrie et du Liban, formed in 1919 to take over the former BIO branches in those countries, had its Syrian activity nationalized in 1956 following the Suez Crisis, and merged into the state-owned Commercial Bank of Syria in 1966. The Lebanese operation lost its issuance privilege in 1963 following the creation of the country's central bank, the Banque du Liban;[19] its commercial activities were regrouped into a newly formed Société Nouvelle de la Banque de Syrie et Liban (SNBSL), which lasted until 1970.[citation needed]

In 1956, Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized all Ottoman Bank operations in Egypt, and transferred them to the purposed-created Bank Al-Goumhourieh together with those of Ionian Bank. In 1969, the BPPB sold the remaining operations of the London-led group to National and Grindlays Bank. In 1975, Grindlays also purchased the Paris commercial branch and affiliated operations in Switzerland, which were renamed Grindlays Banque - France.[18] Grindlays, in turn, was acquired in 1984 by the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group.

Merger into Garanti Bank

In 1996, Paribas ceded its control of the Ottoman Bank to Garanti Bank, by then a fully-owned subsidiary of the Doğuş Group. On 31 July 2001, Garanti merged the Ottoman Bank with Körfez Bank, and on 21 December 2001, integrated it fully into its own operations.[20] This led to the disappearance of the Ottoman Bank brand name from all remaining branches. At the time of its merger, the Ottoman Bank had a network of 58 branches and around 1,400 personnel.[21]

Human resources and leadership

The Ottoman Bank was set up as an institution in which people from multiple nationalities would work, even though the nationality of its most senior executives was the matter of numerous negotiations over the years.

The General Manager in Constantinople and their deputy were British or French, even though during World War I the BIO was administered by Ottomans of Armenian and Greek ethnicity as British and French nationals had to leave the country at war. The top executives and most of the branch managers were Europeans. Many mid-level officers and some branch managers were non-Muslim Ottomans of Greek, Armenian, Jewish and Arab Christian background. The bottom of the hierarchy was mostly Muslim Ottomans performing services as clerks, couriers, guards and doorkeepers.

Compared to the proportion of the different population of the empire, the number of the non-Muslim personnel was comparatively high, partly reflecting the fact that non-Muslims had better access to western language skills, accounting and banking education, and culturally western orientation until the forming of the Republic of Turkey.[22]

Chairmen

First Ottoman Bank

- Austen Henry Layard (1856-1861)

- Thomas Charles Bruce (1861-1862)

- Sir William Clay (1862-1865)

BIO London Committee

- Sir William Clay (1863-1866)

- Austen Henry Layard (1866-1870)

- Thomas Charles Bruce (1870-1890)

- Charles Mills, 1st Baron Hillingdon (1890-1898)

- Charles Mills, 2nd Baron Hillingdon (1898-1907)

- Edward Ponsonby (1907-1920)

- George Goschen (1920-1924)

- Herbert Lawrence (1924-1943)

BIO Paris Committee

- Charles Mallet (1863-1902)

- Rodolphe Hottinguer (1902-1919)

- Jean de Neuflize (1919-1928)

- Raoul Mallet (1928-1937)

- Charles Rist (1937-1954)

- Emmanuel Monick (1954-1975)

- Bernard de Margerie (1975-1989)

- Gustave Rambaud (1989-1992)

- Hubert de Saint-Amand (1992-1996)

General managers

Constantinople / Istanbul

- Alexandre de Plœuc (1863–1868)

- Augustus Edward Hobart-Hampden (1868-1871)

- Morgan Hugh Foster (1871–1889)

- Edgar Vincent (1889–1897)

- Robert Hamilton Lang (1897–1902)

- Gaston Auboyneau (1902–1903)

- Charles de Cerjat (1903-1904)

- Jules Deffès (1904-1910)

- Paul Révoil (1910-1913)

- Arthur Nias (1913-1919)

- Louis Steeg (1920-1925)

- Jacques Jeulin (1966–1985)

- Aclan Acar (1996–2000)

- Turgay Gönensin (2000–2001)

Paris

From the 1880s to World War I, a Paris-based officer generally known as the administrateur délégué, starting with Théodore Berger who had earlier been the Secretary of the Paris Committee, played a key executive role in running the BIO in close coordination with the management based in Constantinople.

- Théodore Berger (1882-1900)

- Frank Auboyneau (1900-1903)

- Gaston Auboyneau (1903-1911), Frank's son

- Charles de Cerjat (1914-?)

Branch network

The bank had an extensive domestic and international branch network; the boundaries between the two subsets changed over time with the gradual shrinkage of the Ottoman Empire's territory. In 1856, the Ottoman Bank started with offices in London and Constantinople, and opened branches that same year in the two key ports of Smyrna (now Izmir) and Beirut as well as in Galaţi in Moldavia. 1866 the BIO opened its first Egyptian branch in Alexandria. In Paris, it complemented the local committee with a commercial office in 1868, which moved in 1870 to a prestige building facing the Palais Garnier.

In Romania, the Galaţi branch and another one created in 1861 in Bucharest were transferred in 1866 to the newly established Bank of Romania. In Bulgaria, the BIO had intermittent presence with branches in Ruscuk/Ruse (1875-1880, reopened 1892-1899), Philippopoli/Plovdiv (1878-1899), Varna (1880-1882), and Sofia (1890-1899). Following the Balkan Wars, the BIO's branches in what is now North Macedonia (Monastir/Bitola and Üsküb/Skopje) were taken over in 1914 by the Banque franco-serbe (BFS), in which the BIO had an equity interest which it retained until the BFS's nationalization in 1939.

Network in 1914

An advert from early 1914 lists 83 branches, sub-branches and offices, in addition to the three head office locations of Galata, London and Paris:

- 4 in the remaining Ottoman lands in Europe: Stamboul (now Eminönü, opened 1886) and Pera (now İstiklal Avenue 115/A, 1891) in Constantinople; Edirne (1875) and Rodosto/Tekirdağ (1909) in East Thrace;

- 42 in Ottoman Anatolia: Smyrna (1856), Aydın and Afyonkarahisar (1863), Adalia/Antalya (1869), Bursa (1875), Nazilli (1881, with interruption 1898-1905), Adana and Konya (1889), Denizli (1890), Balıkesir, Uşak, Samsun and Trabzon (1891), Mersin (1892), Ankara (1893), Castambol/Kastamonu and Sivas (1899), Eskişehir and Akşehir (1904), Panderma/Bandırma and Bilecik (1905), Erzurum, Kerassunde/Giresun, Kütahya and Aintab/Gaziantep (1906), Adapazarı (1907), Tarsus (1908), Césarée/Kayseri, İnebolu, Ordu, Geyve and Bolvadin (1910), Diyarbakır, Kharput/Mamuret-el-Aziz/Elazığ, Bitlis, Van and Djihan/Ceyhan (1911), Bolu, Urfa, Sandıklı and Sokia/Söke (1912), and Dardanelles/Çanakkale (1914);

- 15 in the Arab-speaking Ottoman territories: Beirut (1856), Damascus (1875), Baghdad (1892), Aleppo and Bassorah (1893), Tripoli (1904), Jaffa and Jerusalem (1905), Haifa (1906), Mosul (1907), Homs (1908), Sidon and Hodeida (1911), Jeddah (1912), and Hama (1914?);

- 3 in the Khedivate of Egypt: Alexandria (1866), Port Said (1872), and Cairo (1881);

- 4 in British Cyprus: Larnaca (1862), Nicosia and Limassol (1879), and Famagusta (1906);

- 14 in European and Aegean territories lost by the Ottoman Empire during the Italo-Turkish War and Balkan Wars of 1911-1913: Shkodër in the fledgling Principality of Albania; Dedeağaç/Alexandroupoli (1904), Xanthi (1906), Gyumyurdjina/Komotini and Soufli (1910) in the Kingdom of Bulgaria; Salonica (1863), Mytilini (1898), Kavala (1904), Drama, Serres and Ioannina (1910) in the Kingdom of Greece; Rhodes (1911) in the Kingdom of Italy; and Monastir/Bitola and Üsküb/Skopje (1903) in the Kingdom of Serbia;

- 1 in the UK: Manchester (1911).

The advert mentions neither the Egyptian branches in Minieh and Mansureh, respectively opened in 1907 and 1910, nor the one in Alexandretta/İskenderun, opened in 1913. The branch in Zahlé was presumably opened later in 1914.

Later developments

The BIO opened branches in Marseille (1916), Paphos (1918), Kirkuk (1920), Tunis (1920), Kermanshah (1920), and Troödos (1921). In 1921 it lost its network in what are now Iraq, Lebanon and Syria as well as in Greece. It nevertheless developed further in Palestine with branches in Bethlehem, Ramallah, and Nablus (1922), and in Iran with Hamadan and Tehran (1922). In 1924 it opened in the Musky neighborhood of Cairo and in Ismailia, as well as Amman in 1925 and Tel Aviv in 1931.

During and after World War II the bank further opened branches in Egypt (El-Geneifa in the Sinai in 1940, Port Tewfik in 1941, El Mahalla El Kubra in 1942, Fayoum and Tanta in 1947), Cyprus (Kyrenia in 1943, Lefka and Morphou in 1946), as well as in West Jerusalem (1947), Erbil (1948), Khartoum and Port Sudan (1949). All Egyptian operations were nationalized in 1956 following the Suez Crisis. Despite that setback, the Ottoman Bank opened new branches in Qatar (1956), Abu Dhabi (1962), and Muscat (1969). All these non-Turkish activities were sold to National and Grindlays Bank in 1969.[18]

Inside Turkey, most of the former Ottoman Bank branches have been maintained as branches of Garanti Bank following the 2001 merger.

Gallery

Branch in Stamboul behind Yeni Cami, 1906 extension on a design by architect Barouh; now a branch of Garanti Bank

Branch in Edirne, 1930; no longer extant

Branch in Dedeagac, early 20th century

Branch in Salonica, after bombing in 1903 by the Bulgarian anarchist Boatmen of Thessaloniki

The same building in 2020, now the State Conservatory of Thessaloniki

Former branch in Monastir, damaged in January 1917 as the Bitola branch of the Banque Franco-Serbe

The same building in 2014, now a branch of Stopanska Banka

Branch in Mytilene, 1906

Branch in Izmir, built in the late 1920s on a design by Giulio Mongeri

The same building in 2007, now a branch of Garanti Bank

Branch in Konya, 1930

Branch in Sivas, 1930

Branch in Samsun, 1930

The same building in 2016, now a branch of Garanti Bank

Branch in Beirut, 1906; no longer extant

Branch in Jerusalem, 1960

Same building in 1999, by then an ANZ branch still bearing the Ottoman Bank name; now Al-Hayat Medical Center

Branch in Tehran, interwar period

Branch in Kampala, 1960

Branch in Dar es Salaam, 1960

Branch in Nairobi from 1956 to 1969, designed by R. H. Robertson and built in the 1920s,[24] now a Stanbic branch

Galata head office

In the late 1880s, the Imperial Ottoman Bank decided to commission a new headquarters building on Voyvoda Street in Galata, now Bankalar Caddesi in Karaköy, Istanbul, which would also serve as headquarters for the Ottoman Tobacco Company, also known as the Régie, in which the BIO was the main investor. Architect Alexander Vallaury designed the building for that purpose, with an east-west division between the two entities and separate street entrances (the BIO on No.11 and the Tobacco Régie on No.13); and a north-south stylistic division between the Western-looking street front and the neo-Ottoman, asymmetric rear façade that arose prominently above the Golden Horn. Thus, Vallaury's design embodied the BIO's unique identity as a bridge between Western European capitalism and Ottoman statehood.

The building was inaugurated on 27 May 1892 and was kept in use by the Ottoman Bank until 1999. In 1896, it was the site of the occupation of the Ottoman Bank by activists of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation in the context of the Hamidian massacres. From 1999 to 2009, it housed the Karaköy branch of Garanti Bank and its area directorates, as well as the Ottoman Bank Archives and Research Centre. It was then closed for refurbishment and reopened in November 2011 as the Galata site of SALT, a cultural institution that is funded by Garanti Bank, complementing SALT's other Istanbul site on İstiklal Avenue, formerly Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center.

SALT operates the Ottoman Bank Museum in the building together with a café, a bookstore, an auditorium, temporary exhibition spaces, a public library, and an archive that is open to the public (Açık Arşiv).[25] The twin neighboring building, on Bankalar Caddesi 13, has hosted the Tobacco Monopoly Administration (succeeding the Régie) from 1925 to 1934, and since 1934 has been the Istanbul branch of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey.[26]

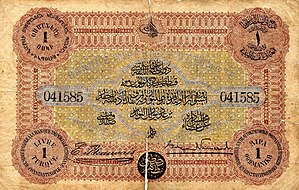

Ottoman Bank Museum

The Ottoman Bank Museum, now operated by SALT, was initially opened in the building's basement and expanded into the upper floors in 2017.[26] It displays objects and provides insight into the late Ottoman and early Republican period, including stock and bond certificates, accounting books, customer files, deposit cards, personnel files and photographs.[27] The basement includes four bank vaults, the largest of which is two-storied and has been repurposed to display the banknotes and silver coins issued between 1863 and 1914 together with the story, design, registration and samples of each.

North front in the 1920s, photographed by Sébah & Joaillier

Entrance hall with inscription that reads "Who Earns Money Is God's Beloved"[28]

Exhibition "Prelude to the 1908 Revolution: The Ottomans in Paris", 2011

See also

- Ottoman Public Debt Administration

- Banque de Salonique

- National Bank of Turkey

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

References

Notes

- ^ "Framed Print of The Imperial Ottoman Bank, Throgmorton Street, London (engraving)". Media Storehouse.

- ^ a b c "Ottoman Bank". London Metropolitan Archive.

- ^ Young, George (1906). Corps de droit ottoman; recueil des codes, lois, règlements, ordonnances et actes les plus importants du droit intérieur, et d'études sur le droit coutumier de l'Empire ottoman (in French). Vol. 5. Clarendon Press. p. 25.

- ^ a b Christopher Clay (November 1994), "The Origins of Modern Banking in the Levant: The Branch Network of the Imperial Ottoman Bank, 1890-1914", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Cambridge University Press, 26:4 (4): 589–614, JSTOR 163804

- ^ Johann Strauss (July 2016). "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire". In Rhoads Murphey (ed.). Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315587967.

- ^ a b c d e f André Autheman (1996). "I. L'Ottoman Bank". La Banque impériale ottomane. Histoire économique et financière - XIXe-XXe. Paris: Institut de la gestion publique et du développement économique : Comité pour l'Histoire Economique et Financière de la France. pp. 1–20. ISBN 9782111294219.

- ^ Arthur Edwin Crouchley (1938), "The Charter of the Bank of Egypt (19 Vict. - 1856)", Bulletin de l'Institut d'Égypte, 21: 31–41, doi:10.3406/bie.1938.3511, S2CID 250468734

- ^ a b c d André Autheman (1996). "II. Création de la Banque impériale ottomane". La Banque impériale ottomane. Histoire économique et financière - XIXe-XXe. Paris: Institut de la gestion publique et du développement économique : Comité pour l'Histoire Economique et Financière de la France. pp. 21–32. ISBN 9782111294219.

- ^ Rondo Cameron; Valeriĭ Ivanovich Bovykin (1992). International Banking 1870-1914. Oxford University Press. p. 407.

- ^ a b c d Nora Şeni; Sophie Le Tarnec (1997). Les Camondo, ou l'éclipse d'une fortune. Babel / Actes Sud.

- ^ a b c d André Autheman (1996). "III. Les débuts de la Banque impériale ottomane". La Banque impériale ottomane. Histoire économique et financière - XIXe-XXe. Paris: Institut de la gestion publique et du développement économique : Comité pour l'Histoire Economique et Financière de la France. pp. 33–56. ISBN 9782111294219.

- ^ a b V. Necla Geyikdağı (2011). "French Direct Investments in the Ottoman Empire Before World War I" (PDF). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Ekrem Karademir (December 2007), Between Stumbling and Fall Towards Insolvency: The Endeavors of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century (PDF), Ankara: Bilkent University

- ^ See Tabitha Morgan, Sweet and Bitter Island (London: Taurus Book, 2010) 70f

- ^ "La Banque ottomane : une structure originale au service de l'Empire ottoman". BNP Paribas. 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Hubert de Saint-Amand nommé à la tête de la Banque Ottomane". Les Échos. 2 October 1991.

- ^ Lorans Tanatar Baruh. "The Imperial Ottoman Bank". Bibliothèque nationale de France / Bibliothèques d'Orient.

- ^ a b c d "History of the Bank". Ottoman Bank Archive.

- ^ Ivy Wang (2019). "A Balance Sheet Analysis of the Banque de Syrie et du Liban" (PDF). Johns Hopkins University.

- ^ "History". Garanti BBVA Investor Relations.

- ^ "Garanti ile Osmanlı birleşiyor".

- ^ Research on Berç Türker Keresteciyan's life page 37-38 Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Phivos Stavrides Foundation - Larnaca Archives". Michelangelo Foundation.

- ^ Washington Mito (16 July 2022). "Inside Nairobi CBD's First Brick Building: Story of a Man Impressing Girlfriend". Kenyans.co.ke.

- ^ "SALT and the Ottoman Bank Museum". Istanbul For 91 Days. 15 June 2013.

- ^ a b "12: SALT Galata". A City That Remembers: Space and Memory from Taksim to Sultanahmet. 31 January 2019.

- ^ "The (Imperial) Ottoman Bank, Istanbul." Edhem Eldem. Financial History Review. Vol 6, 1999, p. 85-95.

- ^ Mustafa Akyol (8 January 2012). "The motto of the late Ottoman Bank: "That who earns money is God's beloved."". Twitter.

External links

![]() Media related to Ottoman Bank at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ottoman Bank at Wikimedia Commons

- Interlanguage link template existing link

- CS1 French-language sources (fr)

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with short description

- Articles containing Turkish-language text

- Articles containing French-language text

- Articles containing Ottoman Turkish (1500-1928)-language text

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2022

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Commons category link is the pagename

- AC with 0 elements

- 1856 establishments in the Ottoman Empire

- 2001 disestablishments in Turkey

- Banks established in 1856

- Economy of the Ottoman Empire

- Former central banks

- Defunct banks of France

- Defunct banks of Turkey

- Defunct banks of the United Kingdom

- Banks disestablished in 2001

![The same building in 2020, now the State Conservatory of Thessaloniki [el]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/%CE%9A%CF%81%CE%B1%CF%84%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C_%CE%A9%CE%B4%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%BF_%CE%98%CE%B5%CF%83%CF%83%CE%B1%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%AF%CE%BA%CE%B7%CF%82_.jpg/120px-%CE%9A%CF%81%CE%B1%CF%84%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C_%CE%A9%CE%B4%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%BF_%CE%98%CE%B5%CF%83%CF%83%CE%B1%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%AF%CE%BA%CE%B7%CF%82_.jpg)

![Branch in Izmir, built in the late 1920s on a design by Giulio Mongeri [tr]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/Ottoman_Bank_%C4%B0zmir_Branch_%2815188377595%29.jpg/77px-Ottoman_Bank_%C4%B0zmir_Branch_%2815188377595%29.jpg)

![Former branch in Larnaca, 2017; now Phivos Stavrides Foundation[23]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3c/Larnaca_01-2017_img09_Old_Ottoman_Bank.jpg/120px-Larnaca_01-2017_img09_Old_Ottoman_Bank.jpg)

![Branch in Nairobi from 1956 to 1969, designed by R. H. Robertson and built in the 1920s,[24] now a Stanbic branch](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/84/Nairobi_Branch_%2814739443358%29.jpg/120px-Nairobi_Branch_%2814739443358%29.jpg)

![Entrance hall with inscription that reads "Who Earns Money Is God's Beloved"[28]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/SALT_Galata_in_1990_%2814666124881%29.jpg/120px-SALT_Galata_in_1990_%2814666124881%29.jpg)