Russian occupation of Kherson Oblast

Kherson Oblast

Херсонська область | |

|---|---|

|

| |

Kherson Oblast: Ukrainian-controlled territory | |

| Occupied country | Ukraine |

| Occupying power | Russia |

| Russian-installed occupation regime | Kherson military-civilian administration[a] (2022) |

| Disputed oblast of Russia | Kherson Oblast[b] (2022–present) |

| Battle of Kherson | 2 March 2022 |

| Annexation by Russia | 30 September 2022 |

| Administrative centre | Kherson |

| Government | |

| • Military Commander | Viktor Bedrik[1] |

| • Head of the MCA | Volodymyr Saldo[2] (Volodymyr Saldo Bloc) |

| • Chair of the MCA | Sergei Yeliseyev |

| • Deputy Chairs of the MCA | Vitaliy Buliuk (Our Land) Ekaterina Gubareva (New Russia Party) Kirill Stremousov (Derzhava) Igor Semenchev (Volodymyr Saldo Bloc) Aslan Arsanukaev Sergey Cherevko |

| Website | khogov |

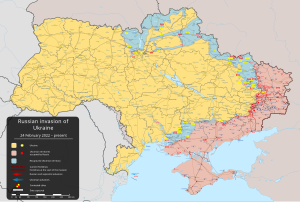

The Russian occupation of Kherson Oblast is an ongoing military occupation, which began on 2 March 2022, in Kherson Oblast, Ukraine. Russia claims the territory of the entire oblast, as well as parts of Mykolaiv Oblast, including areas around Snihurivka and Oleksandrivka,[3][better source needed] and part of the Kinburn Peninsula south of the Dnieper–Bug estuary.[citation needed] The military occupation zone was formed after the Fall of Kherson and most of the oblast, which led to the de facto control of most of the territories of the oblast by the Russian government and its armed forces.[4]

In mid-May 2022, the leadership of the Kherson military-civilian administration announced its intention for the region be annexed by the Russian Federation.[5] Referendums were held in late September for Zaporizhzhia Oblast and Kherson Oblast to join Russia.[6][7] In July, a Russian decree extended Russian 2022 war censorship laws to the Kherson oblast, with deportation to Russia included as a punishment for infringement.[8]

Since 29 August 2022, the Kherson region was the center of the 2022 Ukrainian southern counteroffensive.[9]

Russia annexed Kherson Oblast on 30 September 2022, including parts of the oblast that it did not control at the time.[10] The United Nations General Assembly subsequently passed a resolution calling on countries not to recognise what it described as an "attempted illegal annexation" and demanded that Russia "immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw".[11]

The Russian-installed occupation force was initially called "Kherson military-civilian administration" (Russian: Херсонская военно-гражданская администрация, romanized: Khersonskaya voyenno-grazhdanskaya administratsiya). Its name was changed to "Kherson Oblast" (Russian: Херсонская область, romanized: Khersonskaya oblast) after the Russian annexation. On 19 October 2022, the administration's executive bodies moved from Kherson to the left bank of the Dnipro as part of an evacuation.[12]

Background

On 24 February, Russian forces began an invasion of Ukraine.[13] Fighting began across the Kherson Oblast, resulting in multiple Russian victories.[14][15][16][17] On 2 March, Russian forces captured the capital of the oblast, Kherson,[18] beginning a military occupation of the city and the oblast.[19]

Military occupation

Shortly after Kherson was captured, the Russian Ministry of Defence said talks between Russian forces and city administrators regarding the maintenance of order were underway. An agreement was reached in which the Ukrainian flag would still be hoisted in the city while Russia established the new administration. Mayor Ihor Kolykhaiev announced new conditions for the city's residents: citizens could only go outside during daytime and were forbidden to gather in groups. Additionally, cars were only allowed to enter the city to supply food and medicine; these vehicles were to drive at minimum speeds and were subject to searches. Citizens were warned not to provoke Russian soldiers and obey any commands given.[20]

In the first days of the invasion, Russian forces established control over and unblocked the North Crimean Canal, effectively rescinding a longstanding water blockage imposed on Crimea by Ukraine after the 2014 Russian annexation of the peninsula.[21]

Initial allegations that Russian soldiers had raped 11 women in Kherson, and that six of those women were killed, including a teenager,[22][23] were denied by Hennadiy Lahuta, head of the Ukrainian Kherson Regional State Administration, who stated that such reports were disinformation.[24]

On 5 March, Kolykhaiev said that there was no armed resistance in the city and Russian troops were "quite settled". He requested humanitarian aid, stating that the city lacked power, water, and medicine.[25] Later that day, around 2,000 protesters marched in the city center. The protesters waved Ukrainian flags, sang the national anthem, and chanted patriotic slogans. A video showed Russian soldiers firing into the air to dissuade the protestors. There were also claims that the Russian force had a list of Ukrainian activists in the city that they wanted to capture.[26] On 9 March, the General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces stated that Russia had detained more than 400 people in Kherson due to ongoing protests.[27]

On 12 March, Ukrainian officials claimed that Russia was planning to stage a referendum in Kherson to establish the Kherson People's Republic, similar to the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic. Serhiy Khlan, deputy leader of the Kherson Oblast Council, claimed that the Russian military had called all the members of the council and asked them to cooperate.[28] Lyudmyla Denisova, Ombudsman of Ukraine, stated that the referendum would be illegal because "under Ukrainian law any issues over territory can only be resolved by a nationwide referendum".[29] Later that day, the Kherson Oblast Council passed a resolution stating that the proposed referendum would be illegal.[30]

On 13 March, Ukrayinska Pravda, a Ukrainian newspaper, reported that several thousand people in Kherson took part in a protest.[31] Russian soldiers dispersed the protest with gunfire, stun grenades, and rubber bullets, injuring several people.[32][33]

On 22 March, the Ukrainian government warned Kherson was facing a "humanitarian catastrophe" as the city was running out of food and medical supplies and accused Russia of blocking evacuation of civilians to Ukraine-controlled territory.[34][35] Russia countered by saying that its military helped deliver aid to the city's population.[36] A local journalist stated that there was only a staged event, in which former prisoners from Crimea were brought in to act as locals welcoming the Russians and accepting their assistance.[37] According to several media outlets, residents report intrusive checkpoints, abductions, and Russian looting of shops.[38][39]

Military-civilian administration

By the beginning of April, Russian flags began to be displayed in Kherson Oblast.[40][41]

On 18 April, Igor Kastyukevich, a Russian politician and deputy of the 8th State Duma, was allegedly appointed by the Russian government as a de facto mayor for Russian forces on 2 March.[42][43] Kastyukevich denied these reports.[44]

On 25 April 2022, Ihor Kolykhaiev announced that Russian forces had taken control of the Kherson City Council building.[45]

On 26 April, both local authorities and Russian state media reported that Russian troops had taken over the city's administration headquarters and had appointed a new mayor,[46] former KGB agent Oleksandr Kobets, and a new civilian-military regional administrator, ex-mayor Volodymyr Saldo.[47] The next day, Ukraine's Prosecutor General said that troops used tear gas and stun grenades to disperse a pro-Ukraine protest in the city centre.[46]

In an indication of an intended split from Ukraine, on 28 April the new military-civilian administration announced that from May it would switch the region’s currency to the Russian ruble. Additionally, citing unnamed reports that alleged discrimination against Russian speakers, its deputy head, Kirill Stremousov said that "reintegrating the Kherson region back into a Nazi Ukraine is out of the question".[48]

On 27 April, the Legislative Assembly of Krasnoyarsk Krai in Siberia approved the expropriation of grain from the Kherson region. Agricultural machinery from the occupied Kherson region was also transported to remote Russian lands, including Chechnya.[49] Lyudmila Denisova, the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, has compared this to repeating the Holodomor, a famine in Soviet Ukraine in 1932-1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians.[50]

On 29 April, Saldo stated that the official languages of the Kherson Oblast would be both Ukrainian and Russian and that the International Settlements Bank from South Ossetia would open 200 branches in Kherson Oblast soon.[51]

On 1 May, a four-month plan was adopted for a full transition to rubles. At the same time, the Ukrainian hryvnia was to remain the current currency along with the ruble for four months.[52]

On 7 May, a new coat of arms was adopted, based on the 1803 coat of arms of Kherson of the Russian Empire.[53][54][55][56]

On 9 May, an Immortal Regiment event took place in the city, celebrating Victory Day. Soviet-era victory flags and red banners were flown.[57]

On 11 May 2022, Kirill Stremousov announced his readiness to send President Vladimir Putin with a request for Kherson Oblast to join the Russian Federation, noting that there would be no creation of the "Kherson People's Republic" or referendums regarding this matter.[5] Commenting on these statements, Putin's press secretary Dmitry Peskov said that this issue should be decided by the inhabitants of the region and that "these fateful decisions must have an absolutely clear legal background, legal justification, be absolutely legitimate, as was the case with Crimea".[58]

On 30 May, Russia claimed that it had started exporting last year’s grain from Kherson to Russia. They were also working on exporting sunflower seeds.[59] According to locals, Russian soldiers were being employed as strawberry pickers in Kherson Oblast.[60]

On 3 June, the EU stated that it wouldn’t recognize any Russian passports issued to Ukrainian citizens in the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions.[61] On 11 June, according to local officials, the first Russian passports were handed out to citizens in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Region, including local officials such as Volodymyr Saldo.[62][63]

According to Ukrainian authorities, at the beginning of July, People's Deputy of Ukraine Oleksii Kovalov assumed the position of deputy head of the government of Kherson Oblast.[64] Kovalov was shot dead in his own home on 29 August 2022.[65][64]

Composition

The military commander and the head of the administration are in charge of the administration, which includes:[66]

| Name | Position |

|---|---|

| Volodymyr Saldo Sergei Yeliseyev |

Head of Administration Acting Head of Administration |

| Vitaly Buliuk | First Deputy Head of Administration for Economics, Financial and Budgetary Policy, Agriculture, Revenues and Fees |

| Ekaterina Gubareva | Deputy Head of Administration for Digitalization, Communications, Legal Regulation, Domestic and Foreign Policy |

| Kirill Stremousov | Deputy Head of Administration for Family, Youth, Sports and Information Policy |

| Igor Semenchev | Deputy Head of Administration for Fuel and Energy Complex, Industry and Trade |

| Aslan Arsanukayev | Deputy Head of Administration for Capital Construction, Housing, Transport and Natural Resources |

| Sergey Cherevko | Deputy Head of Administration for Education, Science, Culture, Health and Social Protection of the Population |

Administrative division

According to the occupation administration, the Kherson Military-Civilian Administration is divided into 5 districts, 49 territorial municipalities, within which there are 298 settlements.[67] Thus, the military-civilian administration includes Kherson Raion, Beryslav Raion, Skadovsk Raion, Kakhovka Raion and Henichesk Raion. In fact, the administrative division of the Kherson Oblast and the division of the military-civilian administration do not have any significant differences, and the military-civilian administration simply copied the division of Ukraine so it retained, among other things, the Ukrainian system of administrative divisions.

Torture and abduction of civilians by Russian forces

Dementiy Bilyi, head of the Kherson regional department of the Committee of Voters of Ukraine, claimed that the Russian security forces were "beating, torturing, and kidnapping" civilians in the Kherson Oblast of Ukraine. He added that eyewitnesses had described "dozens" of arbitrary searches and detentions, resulting in an unknown amount of abducted persons.[68] At least 400 residents had gone missing by 16 March, with the mayor and deputy mayor of the town of Skadovsk being allegedly abducted by armed men.[69] An allegedly leaked letter described Russian plans to unleash a "great terror" to suppress protests occurring in Kherson, stating that people would "have to be taken from their homes in the middle of the night".[70]

Ukrainians who escaped from occupied Kherson into Ukrainian-controlled territory provided testimonies of torture, abuse and kidnapping by Russian forces in the region. One person, from Bilozerka in Kherson Oblast, provided physical evidence of being tortured by Russians and described beatings, electrocutions, mock executions, strangulations, threats to kill family members and other forms of torture.[71]

An investigation by BBC News gathered evidence of torture, which in addition to beatings also included electrocution and burns on people's hands and feet. A doctor who treated victims of torture in the region reported: "Some of the worst were burn marks on genitals, a gunshot wound to the head of a girl who was raped and burns from an iron on a patient's back and stomach. A patient told me two wires from a car battery were attached to his groin and he was told to stand on a wet rag". In addition to the BBC, Human Rights Watch and the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine have reported on torture and disappearances carried out by Russian occupation forces in the region. One resident stated: "In Kherson, now people go missing all the time (...) there is a war going on, only this part is without bombs."[72]

Kherson's elected Ukrainian mayor compiled a list of more than 300 people who had been kidnapped by Russian forces as of 15 May 2022. According to The Times, in the building housing the Russian occupation authorities, the screams of the tortured can be frequently heard throughout the corridors.[73]

According to The Washington Post, by 15 April 824 graves had been dug at Kherson's cemetery.[74]

On 22 July 2022, Human Rights Watch reported that Russian forces had tortured, unlawfully detained, and forcibly disappeared civilians in the occupied areas of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions. The purpose of the abuse seemed to be to obtain information and to instil fear so that people would accept the occupation, as Russia seeks to assert sovereignty over occupied territory in violation of international law.[75]

Resistance to occupation

According to Nezavisimaya Gazeta, the activities of the Russian-installed Salvation Committee for Peace and Order encounter constant resistance among the population, and a number of its members were killed by Chief Directorate of Intelligence (GUR) or Ukrainian partisans.[76] Newsweek also reports that two local high-profile pro-Russian figures were shot dead in Kherson by the Ukrainian resistance.[77]

On 5 March, residents of Kherson went to a rally with Ukrainian flags and chanted that the city is still Ukrainian and will never be Russian, despite Russian occupation. The Russian military opened warning fire against the protesters. At the same time, the National Police of Ukraine published a video where a Kherson police officer, holding a Ukrainian flag in his hands, jumped onto a Russian armored personnel carrier that was driving past the rally, and local residents supported his action with shouts and applause.[78]

On 7 March, the Kherson Regional Prosecutor's Office of Ukraine, on the basis of Part 2 of Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (violation of the laws and customs of war, associated with premeditated murder), opened a criminal case into the death of several protesters in Nova Kakhovka. According to the investigation, during a rally on 6 March, the Russian military opened fire on protesters indiscriminately "despite the fact that people were unarmed and did not pose any threat," resulting in at least one death and seven injuries.[79]

On 20 March, protesters in Kherson confronted several Russian military vehicles and told them to "go home".[80] New rallies against the occupation happened on 11 and 27 April, both of which were violently dispersed by Russian occupation forces and separatist militias, killing four people in the process.[81] The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars reports that medical workers in Kherson refused to go to work, in order to boycott Russian occupation forces and not treat their injured.[82]

On 20 April, regional media from Odessa reported that pro-Russian blogger Valery Kuleshov had been killed by Ukrainian partisans in Kherson.[83]

On 6 August, deputy head of the Russian administration in Nova Kakhovka, Vitaly Gura, was shot dead in his home.[84] In September 2022, information emerged that Gura’s assassination had been faked by the FSB.[85]

Ukrainian counter-attacks

On 23 April 2022, Ukraine's Ministry of Defence claimed a strike on a Russian 49th Combined Arms Army command post near Kherson, saying it killed two generals and critically injuring one. The names of the generals were not released.[86][87]

On 24 April 2022, the Ukrainian Operational Command South reported that the Ukrainian army had liberated eight settlements in Kherson Oblast.[88]

On 27 April 2022, the Ukrainian Air Force struck the Kherson TV Tower with a missile temporarily forcing Russian television off-air.[89]

On 10 July, Iryna Vereshchuk, the Deputy Prime Minister of Ukraine urged civilians in the Kherson region to evacuate ahead of a future Ukrainian counterattack.[90]

On 27 July 2022 the surface of a section of the Antonivka Road Bridge was rendered unusable for heavy equipment,[91] by M142 HIMARS attacks.[92]

On 4 September 2022, president Zelenskyy announced the liberation of two villages in Kherson Oblast. Ukrainian authorities released a photo showing the raising of the Ukrainian flag in Vysokopillia by Ukrainian forces.[93][94]

On 6 September 2022, Ukraine confirmed reports that the villages of Liubymivka and Novovoskresenske, southeast of Vysokopillia, had been recaptured by the AFU.[95]

Control of settlements

See also

- Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine

- Russian occupation of Crimea

- Russian occupation of Chernihiv Oblast

- Russian occupation of Donetsk Oblast

- Russian occupation of Kharkiv Oblast

- Russian occupation of Kyiv Oblast

- Russian occupation of Luhansk Oblast

- Russian occupation of Mykolaiv Oblast

- Russian occupation of Sumy Oblast

- Russian occupation of Zaporizhzhia Oblast

- Russian occupation of Zhytomyr Oblast

- Snake Island during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

- Russian annexation of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts

- 2022 protests in Russian-occupied Ukraine

- Ukrainian resistance during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

Notes

References

- ^ "Полковник Бедрик: пропагандисти "засвітили" ймовірного окупаційного коменданта Херсонської області". Центр журналистских расследований. 23 April 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ "Kherson mayor refuses to cooperate with collaborators and invaders". Ukrinform. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Два округа Николаевской области включены в состав Херсонской". lentv24.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ Schwirtz, Michael (2 March 2022). "First Ukraine City Falls as Russia Strikes More Civilian Targets". The New York Times. 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Оккупационные власти Херсона заявили о плане включить регион в состав России". Радио Свобода (in Russian). Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ N/A, N/A (16 July 2022). "Russia plans to hold referendums in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts on 11 September Ukrainian intelligence". Yahoo News. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ France-Presse, Agence (16 July 2022). "Ukraine's occupied Zaporizhzhia eyes Russia 'referendum' in autumn". Firstpost. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Psaropoulos, John (21 June 2022). "Russia resumes eastern Ukraine offensive and expands war aims". Al Jazeera Media Network.

- ^ "Kherson: 'Heavy fighting' as Ukraine seeks to retake Russian-held region". BBC News. 30 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine war latest: Putin declares four areas of Ukraine as Russian".

- ^ "Ukraine: UN General Assembly demands Russia reverse course on 'attempted illegal annexation'". 12 October 2022.

- ^ "Власти Херсона переедут на левый берег Днепра". РБК (in Russian). Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "Putin announces formal start of Russia's invasion in eastern Ukraine". Meduza. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Nova Kakhovka has fallen to Russia: Ukraine media". The Business standard. 27 February 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

Its mayor Volodymyr Kovalenko has reportedly said that Russian troops have seized the city's executive committee and removed all Ukrainian flags from buildings

- ^ "Part of Kherson region territory occupied by aggressor – Regional Administration". Interfax Ukraine. Kyiv. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Mayor of southern Ukrainian town says Russians have taken control". CNN News. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Korobova, Marina (1 March 2022). ""Мелитополь не сдался, Мелитополь – временно оккупирован" – городской голова о ситуации на 1 марта". Mestnyye Vesti (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Schwirtz, Michael; Pérez-Peña, Richard (2 March 2022). "First Ukraine City Falls as Russia Strikes More Civilian Targets". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Kherson: How is Russia imposing its rule in occupied Ukraine?". BBC News. 11 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ James, Liam (3 March 2022). "Russian claims it has seized Kherson as city's mayor agrees to curfew". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Schwirtz, Michael; Schmitt, Eric; MacFarquhar, Neil (25 February 2022). "Russia Batters Ukraine With Artillery Strikes as West Condemns Invasion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Kherson: Girls are asked to stay at home and not go outside. There are rape cases". Rubryka. 3 March 2022. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Steinbuch, Yaron (4 March 2022). "Ukrainian woman claims Russian troops raping women in Kherson". New York Post. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "With fakes about the situation in Kherson, the enemy wants to cause panic and destabilization". Mail BD. 5 March 2022. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Kherson has no more armed resistance against Russia forces, mayor tells CNN". 5 March 2022. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "War in Ukraine: Thousands march in Kherson against occupiers". BBC. 5 March 2022. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Shelling continues to hamper civilian flight as Kremlin decries U.S. oil sanctions". Ynet. 9 March 2022. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Russia plotting sham referendum to create 'Kherson People's Republic', says Ukrainian official". inews.co.uk. 12 March 2022. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ AFP. "Ukraine says Russia plotting to create a pro-Moscow 'people's republic' in Kherson". www.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine: how Putin could try to split the country into regional puppet governments". The Conversation. 14 March 2022. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) In Kherson, thousands of people rallied against the occupier, and the Russians opened fire Archived 13 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrayinska Pravda (13 March 2022)

- ^ "Russian soldiers fire on Kherson protesters". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine says Russian forces violently disperse Kherson protest". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine says 300,000 people are running out of food in occupied Kherson". Reuters. 22 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Medicine shortages and Russian army searches: life in occupied Kherson". France 24. 31 March 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine: UN chief calls on Russia to end 'unwinnable' war — as it happened | DW | 22 March 2022". Deutsche Welle. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Kherson Diary: A first-hand account documenting three weeks of life in a Russian-occupied Ukrainian city. Posted by The Guardian". The Milwaukee Independent. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Peterson, Scott; Naselenko, Oleksandr (6 April 2022). "Tear gas, arrogance, and resistance: Life in Russia-occupied Kherson". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche, Snapshot of daily life in Russia-occupied Kherson | DW | 2 April 2022, retrieved 7 April 2022

- ^ Bowman, Verity (11 April 2022). "'Intimidating' Russian soldiers tear down Ukraine flag in occupied Kherson". The Telegraph. 0307-1235. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Херсонщина: в Олешках на будівлі адміністрації окупанти вивісили російський прапор". www.radiosvoboda.org. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Окупанти призначили нового "мера" Херсона (фото)" (in Ukrainian). UA News. 18 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "В Херсоні росіяни призначили окупаційного "голову"" (in Ukrainian). 18 April 2022. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Игорь Кастюкевич опроверг слухи о его назначении на должность главы Херсона". ИА REGNUM (in Russian). Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Russian invaders seize building of Kherson City Council – mayor". Ukrinform. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ a b Prentice, Alessandra; Zinets, Natalia (27 April 2022). "Russian forces disperse pro-Ukraine rally, tighten control in occupied Kherson". Reuters. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Times, The Moscow (28 April 2022). "Russian-Occupied Kherson Names New Leadership Amid Pro-Ukraine Protests, Rocket Attacks". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Vasilyeva, Nataliya (28 April 2022). "Occupied Kherson will switch to Russian currency, puppet government says". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Looting Officially: Russia intends to steal grain and other products from occupied Ukraine". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia can cause famine in Ukraine and the world again". Національний музей Голодомору-геноциду. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Назначенный РФ "руководитель" Херсонской области заявил об открытии в регионе банка, который работает в "ЛДНР"". strana.news (in Russian). Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Brian Evans. "The Kremlin orders a Russian-occupied city in Ukraine to start using rubles, state media says". Markets Insider. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Invaders want to make residents of Kherson Oblast take Russian citizenship". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Херсонская область вернет герб времен Российской империи - Газета.Ru | Новости". Газета.Ru (in Russian). Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Invaders want to make residents of Kherson Oblast take Russian citizenship". english.nv.ua. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Герб Херсона". Heraldicum (in Russian). Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Russians hold parades with Soviet flags in occupied Ukrainian cities". Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine's Occupied Kherson Seeks to Join Russia, Moscow-Installed Leader Says". WSJ. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Vasilyeva, Nataliya (30 May 2022). "Russian-controlled Kherson region in Ukraine starts grain exports to Russia - TASS". Reuters. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Russian soldiers seek jobs in Kherson Oblast". Yahoo.com. 2 June 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine: Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the EU on attempts of the Russian Federation to forcefully integrate parts of Ukrainian territory". 3 June 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "First Russian passports issued in occupied areas of Ukraine". www.BBCcom. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Meditation Drums And Caribbean Kidnappings: Meet Russia's 'Governor' In Ukraine's Kherson". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Ukrainian collaborator killed in Kherson Oblast". Ukrainska Pravda. 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

"На Херсонщині вбили нардепа-зрадника Ковальова – джерело". Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022. - ^ "В Росії офіційно підтвердили смерть нардепа зрадника Ковальова". Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "Структура администрации". Официальный сайт Администрации Херсонской области. 17 June 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Херсонская ВГА (16 June 2022). "Херсонская область". Официальный сайт Администрации Херсонской области (in Russian).

- ^ "Russian military abducts, tortures people in Kherson region". www.ukrinform.net. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "In A Ukrainian Region Occupied By Russian Forces, People Are Disappearing. Locals Fear It's About To Get Worse". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Tucker, Tom Ball, Maxim. "Russia plans kidnapping and violence in 'great terror' to end Kherson protests". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "'I Would Not Have Kidneys Left': Ukrainian Village Deputy Speaks About Russian Torture, Threat". International Business Times. June 2022.

- ^ Davies, Caroline (31 May 2022). "Ukraine war: Stories of torture emerging out of Kherson". BBC News.

- ^ Tucker, Maxim (15 May 2022). "Screams of the tortured echo in Kherson as Putin's puppets prepare to join Russia". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ "Satellite imagery reveals fresh graves in Russian-occupied Kherson". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Ukraine: Torture, Disappearances in Occupied South". Human Rights Watch. 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Rodin, Ivan (21 March 2022). "Пока политический план по Украине не заработал / Политика / Независимая газета". Nezavisimaya Gazeta.

- ^ Brennan, David (21 April 2022). "As Soviet victory flag raised over Kherson, resistance hunts collaborators". Newsweek.

- ^ Martynko, Christina (5 March 2022). "Жители Херсона протестуют под обстрелами российских оккупантов: Мы не боимся! Херсон - это Украина!" [Residents of Kherson protest under fire from Russian invaders: We are not afraid! Kherson is Ukraine!]. KP (in Russian).

- ^ Boyko, Ivan (7 March 2022). "Во время митинга в Новой Каховке оккупанты убили одного человека, а семь - ранили" [During a rally in Nova Kakhovka, the invaders killed one person and wounded seven]. UNIAN (in Russian).

- ^ "Ukraine war: Kherson residents tell Russian forces to 'go home' as they confront military vehicles". Sky News. 21 March 2022.

- ^ "Russians disperse a rally for Ukraine in Kherson - there are four victims". Ukrayinska Pravda. 27 April 2022.

- ^ Kudriavtseva, Natalia (25 May 2022). "Fierce Resistance in Kherson Disrupts the Russian "Liberation" Scenario". Wilson Centre.

- ^ "Notorious pro-Russian blogger Kuleshov was killed in Kherson". Odessa Journal. 21 April 2022.

- ^ "На Херсонщині вбили високопоставленого колаборанта Віталія Гуру". Слово і Діло (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ "Смерть замглавы администрации Новой Каховки оказалась инсценировкой".

- ^ "Russia-Ukraine war: Zelenskiy holds press conference; two Russian generals killed near Kherson, says Ukraine – live". the Guardian. 23 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Cooler than Chornobayivka: the Armed Forces destroyed the command post of the occupiers in the Kherson region". Fakty. 23 April 2022. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian forces liberate eight settlements in southern Ukraine". Twitter. The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Live Updates | Explosions in Ukrainian city of Kherson". Yahoo! News. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Civilians in Kherson urged to evacuate". The Guardian. 10 July 2022.

- ^ Ukrainska Pravda (27 Jul 2022) Video from Antonivka Road Bridge in Kherson shows extensive damage

- ^ Ortiz, John Bacon and Jorge L. "Ukraine warns Kremlin to 'retreat or be annihilated' in Kherson; US pushing deal to free Griner: July 27 recap". USA TODAY. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ Ukraine-Russia live, 4 September 2022

- ^ "Institute for the Study of War". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine update: Russian 'hard points' are falling in Kherson, Kharkiv, and near Izyum". Daily Kos. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- Articles containing Russian-language text

- CS1 Russian-language sources (ru)

- Articles with Ukrainian-language sources (uk)

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 Ukrainian-language sources (uk)

- Use dmy dates from July 2022

- Articles with short description

- Pages using infobox settlement with no coordinates

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles lacking reliable references from October 2022

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2022

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Articles with broken excerpts

- Interlanguage link template existing link

- Russian occupation of Ukraine

- States and territories established in 2022

- Southern Ukraine offensive

- April 2022 events in Ukraine

- Kherson

- History of Kherson Oblast