Nothrotheriidae

| Nothrotheriidae Temporal range: Early Miocene Early Holocene (Irvingtonian-Rancholabrean (NALMA) & Colhuehuapian-Lujanian) (SALMA)

~ | |

|---|---|

| |

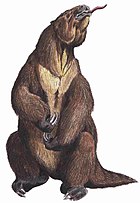

| Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops shastense), Peabody Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Clade: | †Megatheria |

| Family: | †Nothrotheriidae (Ameghino 1920) C. de Muizon et al. 2004 |

| Genera | |

| |

Nothrotheriidae is a family of extinct ground sloths that lived from approximately 19.8 mya—10,000 years ago, existing for approximately 19.79 million years.[7] Previously placed within the tribe Nothrotheriini or subfamily Nothrotheriinae within Megatheriidae, they are now usually placed in their own family, Nothrotheriidae.[8] Nothrotheriids appeared in the Burdigalian, some 19.8 million years ago, in South America. The group includes the comparatively slightly built Nothrotheriops, which reached a length of about 2.75 metres (9.0 ft). While nothrotheriids were small compared to some of their megatheriid relatives, their claws provided an effective defense against predators, like those of larger anteaters today.

Evolution

During the late Miocene and Pliocene, the sloth genus Thalassocnus of the west coast of South America became adapted to a shallow-water marine lifestyle.[8][9][10] However, the family placement of Thalassocnus has been disputed; while long considered a nothrotheriid, one recent analysis moves it to Megatheriidae,[1] while another retains it in a basal position within Nothrotheriidae.[2]

The only known nothrotheriid in North America was Nothrotheriops, which appeared at the beginning of the Pleistocene, about 2.6 Ma ago.[11] Nothrotherium reached Mexico (Nuevo Leon) by the late Pleistocene.[12]

The last ground sloths in North America belonging to Nothrotheriidae, the Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops shastensis), died so recently that their dried subfossilized dung has remained undisturbed in some caves – such as the Rampart Cave, located on the Arizona side of the Lake Mead National Recreation Area – as if it were just recently deposited. A Shasta ground sloth skeleton, found in a lava tube at Aden Crater in New Mexico, still had skin and hair preserved, and is now at the Yale Peabody Museum. The largest samples of Nothrotheriops dung can be found in the collections of the National Museum of Natural History.

Phylogeny

The following sloth family phylogenetic tree is based on collagen and mitochondrial DNA sequence data (see Fig. 4 of Presslee et al., 2019).[13]

| Folivora |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Here is a more detailed phylogeny of the Nothrotheriidae based on Varela et al. 2018.[14]

| Folivora |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ a b Amson, E.; de Muizon, C.; Gaudin, T. J. (2017). "A reappraisal of the phylogeny of the Megatheria (Mammalia: Tardigrada), with an emphasis on the relationships of the Thalassocninae, the marine sloths" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 179 (1): 217–236. doi:10.1111/zoj.12450. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-12.

- ^ a b Varela, L.; Tambusso, P.S.; McDonald, H.G.; Fariña, R.A.; Fieldman, M. (2019). "Phylogeny, Macroevolutionary Trends and Historical Biogeography of Sloths: Insights From a Bayesian Morphological Clock Analysis". Systematic Biology. 68 (2): 204–218. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy058. PMID 30239971.

- ^ A 2017 phylogenetic study moves this subfamily to Megatheriidae,[1] while a 2019 study retains it in Nothrotheriidae.[2]

- ^ PUJOS, FRANçOIS; DE IULIIS, GERARDO; MAMANI QUISPE, BERNARDINO; ADNET, SYLVAIN; ANDRADE FLORES, RUBEN; BILLET, GUILLAUME; FERNáNDEZ-MONESCILLO, MARCOS; MARIVAUX, LAURENT; MüNCH, PHILIPPE; PRáMPARO, MERCEDES B.; ANTOINE, PIERRE-OLIVIER (2016-11-01). "A new nothrotheriid xenarthran from the early Pliocene of Pomata-Ayte (Bolivia): new insights into the caniniform-molariform transition in sloths". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 178 (3): 679–712. doi:10.1111/zoj.12429. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ François Pujos, Gerardo De Iuliis, Bernardino Mamani Quispe & Ruben Andrade Flores (2014) Lakukullus anatisrostratus, gen. et sp. nov., a new massive nothrotheriid sloth (Xenarthra, Pilosa) from the middle Miocene of Bolivia,Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 34:5,1243-1248, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2014.849716

- ^ Gaudin, T. J.; Boscaini, A.; Mamani Quispe, B.; Andrade Flores, R.; Fernández-Monescillo, M.; Marivaux, L.; Antoine, P.-O.; Münch, P.; Pujos, F. (2022). "Recognition of a new nothrotheriid genus (Mammalia, Folivora) from the early late Miocene of Achiri (Bolivia) and the taxonomic status of the genus Xyophorus". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2075744.

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Nothrotheriidae, basic info

- ^ a b Muizon, C. de; McDonald, H. G.; Salas, R.; Urbina, M. (June 2004). "The Youngest Species of the Aquatic Sloth Thalassocnus and a Reassessment of the Relationships of the Nothrothere Sloths (Mammalia: Xenarthra)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 387–397. doi:10.1671/2429a. S2CID 83732878.

- ^ de Muizon, C.; McDonald, H. G.; Salas, R.; Urbina, M. (June 2004). "The evolution of feeding adaptations of the aquatic sloth Thalassocnus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 398–410. doi:10.1671/2429b. JSTOR 4524727. S2CID 83859607.

- ^ Amson, E.; de Muizon, C.; Laurin, M.; Argot, C.; Buffrénil, V. de (2014). "Gradual adaptation of bone structure to aquatic lifestyle in extinct sloths from Peru". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Royal Society of London. 281 (1782): 20140192. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0192. PMC 3973278. PMID 24621950.

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Nothrotheriops, basic info

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Nothrotherium, basic info

- ^ Presslee, S.; Slater, G. J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J. V.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Lezcano, M.; Lanata, J. L.; Southon, J.; Feranec, R.; Bloch, J.; Hajduk, A.; Martin, F. M.; Gismondi, R. S.; Reguero, M.; de Muizon, C.; Greenwood, A.; Chait, B. T.; Penkman, K.; Collins, M.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

- ^ Varela, L.; Tambusso, P. S.; McDonald, H. G.; Fariña, R. A. (2018). "Phylogeny, Macroevolutionary Trends and Historical Biogeography of Sloths: Insights From a Bayesian Morphological Clock Analysis". Systematic Biology. 68 (2): 204–218. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syy058.

External links

Error: "Q16879160" is not a valid Wikidata entity ID.

- Pages with non-numeric formatnum arguments

- Articles with short description

- Articles with 'species' microformats

- Taxonbars desynced from Wikidata

- Taxonbar pages requiring a Wikidata item

- Taxonbars with invalid from parameters

- Taxonbars without secondary Wikidata taxon IDs

- Prehistoric sloths

- Prehistoric mammal families

- Miocene xenarthrans

- Pliocene xenarthrans

- Pleistocene xenarthrans

- Burdigalian first appearances

- Holocene extinctions

- Neogene mammals of South America

- Quaternary mammals of South America

- Quaternary mammals of North America

- Taxa named by Florentino Ameghino