Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5th Senior Officer of the United States Army | |

| In office April 13, 1792 – December 15, 1796 | |

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Arthur St. Clair |

| Succeeded by | James Wilkinson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1791 – March 21, 1792 | |

| Preceded by | James Jackson |

| Succeeded by | John Milledge |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 1, 1745 Easttown Township, Province of Pennsylvania, British America |

| Died | December 15, 1796 (aged 51) Fort Presque Isle, Erie, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Fort Presque Isle, Erie, Pennsylvania, U.S. and St. David's Episcopal Church, Radnor, U.S. |

| Political party | Anti-Administration party |

| Spouse | Mary Penrose |

| Children | Margretta Wayne Isaac Wayne |

| Relatives | Isaac Wayne (father) Samuel Van Leer (brother in-law) |

| Occupation | Soldier |

| Nickname | Mad Anthony |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1775–1783 1792–1796 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and Founding Father of English descent. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his military exploits and fiery personality quickly earned him promotion to brigadier general and the nickname "Mad Anthony".[1] He later served as the Senior Officer of the Army on the Ohio Country frontier and led the Legion of the United States.

Wayne was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and worked as a tanner and surveyor after attending the College of Philadelphia. He was elected to the Pennsylvania General Assembly and helped raise a Pennsylvania militia unit in 1775. During the Revolutionary War, he served in the Invasion of Quebec, the Philadelphia campaign, and the Yorktown campaign. Although his reputation suffered after defeat in the Battle of Paoli, he won wide praise for his leadership in the 1779 Battle of Stony Point.[2] After being promoted to major general in 1783, he retired from the Continental Army soon after. Anthony Wayne was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati of the state of Georgia.[3] In 1780, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[4]

After the war, Wayne settled in Georgia on the Richmond and Kew plantation that had been granted to him for his military service, with Wayne using slaves to manage his plantation.[5] He briefly represented Georgia in the United States House of Representatives where he faced controversy relating to his participation in electoral fraud. Following his financial failures in Georgia, Wayne returned to the Army to accept command of U.S. forces in the Northwest Indian War, where he defeated the Northwestern Confederacy, an alliance of several Native American tribes aided by the British. Following the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers and a subsequent scorched earth campaign of destroying villages, he later negotiated the Treaty of Greenville which ended the war.[6] His victory during the Northwest Indian War resulted in the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans in the Ohio Valley,[7][8][6] and helped pave the way for the future westward expansion of the United States under the doctrine known as manifest destiny.

Wayne's legacy is controversial. His skills as a military leader were criticized by his contemporaries,[9][10] and in recent years, his actions against Native Americans and ownership of slaves have further tarnished his reputation.[11][12]

Early life

Wayne was one of four children born to Isaac Wayne, who had immigrated to Easttown, Pennsylvania, from Ireland, and Elizabeth Iddings Wayne. He was part of a Protestant Anglo-Irish family; his grandfather was a veteran of the Battle of the Boyne, where he fought for the Williamite side.[13] His sister Hannah married his neighbor and fellow United States Army officer Samuel Van Leer.

Wayne was born on January 1, 1745, on his family's 500 acre Waynesborough estate.[14][15] During his upbringing, Wayne would clash with his father's desires that he become a farmer.[16] As a child, his father served as a captain during the French and Indian War, leaving an impression on Wayne who would mimic stories of battles at the time.[15] He was educated as a surveyor at his uncle's private academy in Philadelphia and at the College of Philadelphia for two years.[15] In 1765, Benjamin Franklin sent him and some associates to work for a year surveying land granted in Nova Scotia, and he assisted with starting a settlement the following year at The Township of Monckton.[17]

He married Mary Penrose in 1766, and they had two children. Their daughter, Margretta, was born in 1770, and their son, Isaac Wayne, was born in 1772. Wayne would go on to have romantic relationships with other women throughout his life, including Mary Vining, a wealthy woman in Delaware, leading to himself and his wife to eventually become estranged.[18][19]He would later become a U.S. representative from Pennsylvania.[20]

Wayne was an avid reader and often quoted Caesar and Shakespeare at length while serving in the military.[21] In 1767, he returned to work in his father's tannery while continuing work as a surveyor. At the time, Wayne owned a 40-year-old male slave named Toby, who was registered in Chester County as a "slave for life."[22]

In 1774 after receiving the family farm in Chester County, Pennsylvania, he stepped into the political limelight as the elected chairman of the Chester County Committee of Safety before then being elected into the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly.[23] At the same time, American colonists were reacting both with sword and pen to the British acts imposed on them, setting the stage for the American Revolutionary War.

American Revolution

In 1775, Wayne was nominated to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety beside John Dickinson, Benjamin Franklin, and Robert Morris.[24] Following Great Britain's enactment of the Intolerable Acts, Wayne began to oppose the British and by October 1775, his chairman position for the Chester County Committee of Safety was replaced by a Quaker as citizens described him as a "radical" against the British, an accusation Wayne denied.[24] On January 3, 1776, Wayne was nominated as colonel of the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment by the Pennsylvania delegation of the Second Continental Congress.[24] The poor supplies and controversies between his regiment and the Pennsylvania assembly would later influence Wayne to support the centralization of government.[24]

Regarding tactics, Wayne discarded the conventional line warfare, once stating "the only good lines are those nature made", instead focusing on maneuver warfare and strict discipline.[15] He and his regiment were part of the Continental Army's unsuccessful invasion of Canada where he was sent to aid Benedict Arnold. Wayne commanded a successful rear-guard action at the Battle of Trois-Rivières and then led the forces on Lake Champlain at Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence. His service led to his promotion to brigadier general on February 21, 1777. According to historians, Wayne earned the name "Mad Anthony" because of his angry temperament, specifically during an incident when he severely punished a skilled informant for being drunk.[25][26]

On September 11, 1777, Wayne commanded the Pennsylvania Line at the Battle of Brandywine, where they held off General Wilhelm von Knyphausen in order to protect the American right flank. The two forces fought for three hours until the American line withdrew and Wayne was ordered to retreat.[27] He was then ordered to harass the British rear in order to slow General William Howe's advance towards Pennsylvania. Wayne's camp was attacked on the night of September 20–21 in the Battle of Paoli. General Charles Grey had ordered his men to remove their flints and attack with bayonets in order to keep their assault secret.[28] The battle earned Grey the sobriquet of "General Flint", but Wayne's own reputation was tarnished by the significant American losses, and he demanded a formal inquiry in order to clear his name.

On October 4, 1777, Wayne again led his forces against the British in the Battle of Germantown. His soldiers pushed ahead of other units, and the British "pushed on with their Bayonets—and took Ample Vengeance" as they retreated, according to Wayne's report.[29] Wayne and General John Sullivan advanced too rapidly and became entrapped when they were two miles (3.2 km) ahead of other American units. They retreated as Howe arrived to re-form the British line. Wayne was again ordered to hold off the British and cover the rear of the retreating body.

After winter quarters at Valley Forge, Wayne led the attack at the 1778 Battle of Monmouth, where his forces were abandoned by General Charles Lee and were pinned down by a numerically superior British force. Wayne held out until relieved by reinforcements sent by General George Washington. He then re-formed his troops and continued to fight.[30] The body of British Lt. Colonel Henry Monckton was discovered by the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment, and a legend grew that he had died fighting Wayne.[31]

Wayne would also set an example on coping with adversity during military operations. On October, 1778, Wayne wrote of the brutal cold and lack of appropriate supplies, "During the very severe storm from Christmas to New Year's, whilst our people lay without any cover except their old tents, and when the drifting of snow prevented the green wood from taking fire."[32] Through these tough conditions, Wayne wrote that he sought to keep his soldiers, "well and comfortable."[32]

In July 1779, Washington named Wayne to command the Corps of Light Infantry, a temporary unit of four regiments of light infantry companies drawn from all the regiments in the main army. His successful attack on British positions in the Battle of Stony Point was the highlight of his Revolutionary War service. On July 16, 1779, he replicated the bold attack used against him at Paoli and personally led a nighttime bayonet attack lasting 30 minutes. His three columns of about 1,500 light infantry stormed and captured British fortifications at Stony Point, a cliff-side redoubt commanding the southern Hudson River. The battle ended with around 550 prisoners taken, with fewer than 100 casualties for Wayne's forces. Wayne was wounded during the attack when an enemy musket ball gashed his scalp. The success of this operation provided a small boost to the morale of the army, which had suffered a series of military defeats, and the Continental Congress awarded him a medal for the victory.[26]

On July 21, 1780, Washington sent Wayne with two Pennsylvania brigades and four cannons to destroy a blockhouse at Bulls Ferry opposite New York City in the Battle of Bull's Ferry. Wayne's troops were unable to capture the position, suffering 64 casualties while inflicting 21 casualties on the Loyalist defenders.[33]

On January 1, 1781, Wayne served as commanding officer of the Pennsylvania Line of the Continental Army when pay and condition concerns led to the Pennsylvania Line Mutiny, one of the most serious of the war. He successfully resolved the mutiny by dismissing about half the line. He returned the Pennsylvania Line to full strength by May 1781. This delayed his departure to Virginia, however, where he had been sent to assist General Lafayette against British forces operating there, and the line's departure was delayed once more when the men complained about being paid in the nearly worthless Continental currency.[34]

On July 4, General Charles Cornwallis departed Williamsburg for Jamestown, planning to cross the James River en route to Portsmouth. Lafayette believed he could stage an attack on Cornwallis' rear guard during the crossing. Cornwallis anticipated Lafayette's plan and laid an elaborate trap. Wayne led a small scouting force of 500 at the 1781 Battle of Green Spring to determine the location of Cornwallis, and they fell into the trap; only a bold bayonet charge against the numerically overwhelming British enabled his forces to retreat. The action reinforced the perception among contemporaries that justified the moniker "Mad" to describe Wayne.[35] During the Yorktown campaign, Wayne was shot in the leg; the lead musket ball was never removed from his leg.[36]

After the British under Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Wayne went farther south and disbanded the British alliance with Native American tribes in Georgia.[37] With the goal of establishing peace between settlers and Native Americans, Wayne captured Creek troops early in his time in Georgia, releasing them in order to establish goodwill between the Creek people and the United States.[38] After various skirmishes with Native Americans, Wayne became angered and disenchanted with establishing alliances with Native Americans and in one instance, executed thirty Creek people he captured in July 1783.[38] He then negotiated peace treaties with both the Creeks and the Cherokees during a bout with malaria, for which Georgia purchased a rice plantation for 4,000 guineas and rewarded it to him.[15][37] Wayne would suffer from complications related to malaria for the remainder of his life.[15]

Civilian life

Pennsylvania

In 1783, Wayne returned to Pennsylvania and was celebrated as a hero, deciding to enter politics with other conservative friends at the time.[24] Initially a supporter of democracy, Wayne ultimately grew more authoritarian, believing that the United States should be an aristocracy, supporting the idea of a centralized government controlled by the "aristocratick" property owners, that their interests be maintained, and that the United States military would be controlled by the elites.[24][39] He joined the Federalist Party since he believed he could secure a position among the American elite, aligning himself with the supporters of Washington, and like most federalists, he favored centralization, federalism, modernization, and protectionism.[39][40] He would go on to support Republicanism because Wayne ultimately believed that the United States should have a strong centrally-controlled government, stronger banks, manufacturing, and a standing army and navy.

Wayne would then present himself as a candidate for the Pennsylvania Council of Censors and on election day in October 1783, he gathered troops and approached electoral judges, demanding that they would be allowed to vote.[24] He used his position to protect aristocrats.[24] On October 10, 1783, he was promoted to major general. Wayne was elected to serve in the Pennsylvania General Assembly for two years, becoming even more conservative and defending Tories from persecution.[24]

Georgia

Plantation and slaves

After living in Pennsylvania, Wayne moved to Georgia and had a career in private business running two rice plantations with a total area of 1,134 acres (459 hectares).[41] The plantations, Richmond and Kew, were situated on the Savannah River and had been confiscated from British loyalist Alexander Wright, son of the governor of the Province of Georgia, James Wright.[42][43] Wayne would mortgage his family's Waynesborough estate for 5,000 pounds and purchase 47 slaves – 9 boys, 12 girls, 11 women and 15 men – from Adam Tunno for 3,300 pounds, paying 990 pounds initially and then 2,310 pounds over a five-year period.[16][44][43] A plantation overseer was used by Wayne to direct the actions of his slaves.[16] Letters by Wayne from the time express that he found it difficult to find affordable slaves.[45] Records state that a "number of negroes" were present at the plantations, with the slaves tasked with farming and making various repairs to Wayne's property.[44][43] The plantations were officially given to Wayne in 1786 and he received loans from Dutch bankers for repairs after years of abandonment during a titling process.[16][44] Male slaves would clear land while female slaves would plant rice crops.[16] Wayne also had a personal slave named "Caesar" that he named after his favorite historical figure, Julius Caesar.[46]

Wayne quickly fell into debt running the plantations. His plantations were ultimately unsuccessful as he made poor business decisions and acquired a large debt to Tunno following his slave purchase, later begging various acquaintances to assist him with making payments.[44][47] Wayne approved of slavery and viewed his slaves as passive property.[46][48] When his Georgia possessions were sold, Wayne's advertisement described his slaves as "a Gang of Fifty Country Born and Seasoned Negroes".[46]

During his time in Georgia, his wife abandoned him after rumors of a relationship between Wayne and General Nathanael Greene's wife Catherine spread.[49] While Wayne's wife and family maintained their lives in Pennsylvania, Wayne became a citizen of Georgia in November 1788.[50][51]

Congressman

While in Georgia, Wayne engaged in tormenting politicians and electoral fraud to establish his position.[18] He was a delegate to the state convention that ratified the United States Constitution in 1788 and lost an election to the Senate that same year.[24] In late 1790, he was elected into the 2nd United States Congress as a representative of Georgia's 1st congressional district.[24][52] In what was the first formal complaint of electoral fraud in the United States, Wayne's opponent James Jackson charged that in one country there were less voters than votes counted, Wayne's campaign manager Judge Thomas Gibbons, had prevented voting in another county and that individuals documented as participating in the election later denied voting.[24][53] It was likely that Wayne was aware of Gibbons' act of electoral fraud.[24] While in Congress, Wayne promoted the increased militarization of the United States and supported an act of 5,000 troops entering the Northwest Territory.[24] A House committee determined that electoral fraud had been committed in the 1790 election and Congress voted Wayne out of office on March 16, 1792, and his seat was formally vacated on March 21.[24][54] A special election was held on July 9, 1792, sending John Milledge to fill Wayne's vacant seat, and Wayne declined to run for re-election in 1792.[55][56] As a civilian, Wayne ultimately found himself bankrupt, abandoned by his wife, and removed from office.[57][50][58][56]

Later military career

The Northwest Indian War had been a disaster for the United States, as the British refused to leave the ceded land and continued their involvement in Native American politics. Native Americans also sought to make the Ohio River the border with the United States.[15] Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson's idea of raids had triggered tribes to unite during St. Clair's defeat against General Arthur St. Clair and his troops. Up until that point, it was "the most decisive defeat in the history of the American military"[59] and its largest defeat ever by Native Americans.[60] The death of Major General Richard Butler during St. Clair's defeat, Wayne's closest friend during the revolution, made Wayne particularly upset.[54] Many Native Americans in the Northwest Territory had sided with the British in the Revolutionary War, but the British had ceded any sovereignty over the land to the United States in the Treaty of Paris of 1783. The British were known for persuading Native Americans to fight for them and continued to do so.[61] Although the British were reluctant to directly engage the United States, historian Reginald Horsman writes of their involvement in organizing Native American support, "The Indian Department at Detroit had done all within its power to bolster northwestern Indian resistance to American expansion. The agents had acted as organizers, advisers, and suppliers of the Indians, and they had made it possible for an Indian army to face Wayne."[62]

The United States formally organized the region in the Land Ordinance of 1785 and negotiated treaties allowing settlement, but the Northwestern Confederacy refused to acknowledge them. After the treaties, American settlers started to flood the region and set the foundation for manifest destiny. The Native Americans living in the region quickly became embroiled in conflicts after some support from the British while defending their land from American settlers. The skirmishes resulted with 1,500 deaths over a period of seven years.[15][62]

Interested in maintaining his interests in Georgia, Wayne wrote to President Washington in the spring of 1789 asking to "organize & discipline a Legionary Corps," writing that "Dignity, wealth, & Power" in the United States could only be achieved by the military.[63] United States Secretary of War Henry Knox would agree with Wayne in July 1789 writing "the sword of the Republic only, is adequate to guard a due administration of Justice, and the preservation of the peace," believing that treaties with Native Americans were worthless.[63] At a time of his life when Wayne experienced a shameful political and personal status, President Washington recalled Wayne from civilian life to lead an expedition in the British-led Northwest Indian War, with Wayne's continued bitterness towards Native Americans at the time of his appointment from his previous interactions.[64][65]

While historians generally agree that Wayne's negative attitude towards Native Americans impacted his actions during the Northwest Indian War, Wayne was also deeply motivated by his love for a young United States and the need to set the nation up for future success. In May of 1793, Wayne wrote to then Secretary of War Henry Knox, "Knowing the critical situation of our infant nation and feeling for the honor and reputation of the government which I shall support with my latest breath, you may rest assured that I will not commit the legion unnecessarily."[32] Samuel W. Pennypacker, a former governor of Pennsylvania and president of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, goes on to elaborate on Wayne's perceived importance of American demonstrations of strength, "Wayne had reached the conclusion that we should never have a permanent peace until the Indians were taught to respect the power of the United States, and until the British were compelled to give up their posts along the shores of the lake.”[32]

The confederacy achieved major victories in 1790 and 1791 under the leadership of Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Little Turtle of the Miami tribe. The tribes were encouraged to refuse peace treaties and supported by the British, who also refused to evacuate their own fortifications in the region as stipulated in the Treaty of Paris, citing that the American refusal to pay the debt agreements in the treaty meant that the treaty was not yet in effect, strengthened the tribe's resistance against the United States.[66]

At the same time, Washington was under congressional investigation and needed to raise a larger army to protect the borders against the British and their allied tribes. He felt his best choice was to recruit country-loyal Wayne to take on this daunting task despite Wayne's recent past. Injured, with swollen legs and recurring malaria, Wayne accepted command of the new Legion of the United States in 1792.[67] Washington would allot an extraordinary budget for Wayne to triple the size of the army, administering $1 million, or about 83% of the federal budget, to establish control of the Northwest territory through 1,280 enlisted soldiers.[6][68][69] Under the direction of Washington's policies, Wayne battled the Native Americans he encountered, destroying their villages and food stocks before the winter in order to make them more vulnerable to the elements.[26]

Command of the Legion of the United States

Upon accepting his new position, Wayne said, "I clearly foresee that it is a command which must inevitably be attended with the most anxious care, fatigue, and difficulty, and from which more may be expected than will be in my power to perform."[70] As the new commanding officer for the Legion of the United States, Wayne was first tasked with increasing the number of soldiers in his force. He began his recruiting efforts in the Spring of 1792 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Although recruiting proved to be a difficult effort with the failures of past American expeditions still fresh, Wayne eventually was able to successfully boost the number of soldiers in the Legion.[69]

Wayne then established Fort Lafayette on September 4, 1792, as a frontier settlement from Fort Pitt.[71] Based on earlier failures of American generals, it was vital to train new soldiers and prepare them for new conflicts. Wayne established a basic training facility at Legionville to prepare professional soldiers for the reorganized army, stating that the area near Pittsburgh was "a frontier Gomorrah" that distracted troops.[71] Using the Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States authored by Prussian military officer Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, Wayne began to train his troops.[71] This was the first attempt to provide basic training for regular Army recruits, and Legionville was the first facility established expressly for this purpose. Wayne set up a well-organized structure of sub-legions led by brigadier generals, seen as forerunners of today's brigade combat teams.[72] Wayne was a strict disciplinarian and executed several troops for offenses.[71] Two soldiers were executed for sleeping at their posts.[15] He required his soldiers to adhere to a sharp dress code, with each sub-legion having a distinctive cap and regimental standards with their unit colors.[73] On April 7, 1793, Wayne's troops moved to Fort Washington in Ohio and continued their intense training while also entrenching themselves to repel potential attacks.[71]

Although some experts today are quick to point to the drawbacks of Wayne's severe disciplinary methods, Major John Brooke finds they also helped build confidence among his troops.[69] Each day, he allowed troops to receive half a gill of whiskey with their rations and an extra one for the best shooters. Barrels of rum, whiskey, wine, flour, and rations were stockpiled at various forts and traveled with Wayne's legion.[73] Brooke goes on to write about Wayne's strong relationship with his soldiers, "The winter passed drearily at Greeneville. They were almost in the heart of the Indian country, cut off from communication with the outside world, and surrounded by crafty and treacherous foes. Wayne shared the hardships and privations of his men, and personally saw that discicipline and instruction were kept up. The sentinel on post might know when to expect the conventional visit from the officer of the day, but he never knew at what hour he might see the form of the commander-in-chief emerge from the wintry gloom.”[69] Wayne's support of his soldiers builds on his earlier experiences with his soldiers during the Revolutionary War.[32]

During his command of the Legion of the United States, Wayne also encountered domestic problems en route to securing the Northwest Territory. On May 5, 1793, Wayne entered Cincinnati in preparation for future conflict further West. Although Kentucky was a newly independent state after breaking away from Virginia, many citizens still believed that the United States federal government did little to protect their economic interests in the region. Historian, Paul David Nelson, writes of the local sentiment,"Thus, a few of Kentucky's citizens continued into 1793 to plot all sorts of schemes, including assisting the French to attack Spanish territory, using Kentucky as a base of operations; taking Kentucky out of the federal union and uniting it with the Spanish Empire; and striking a deal with some Canadian citizens to form a separate nation in the West, free from the control of the United States, Britain, or Spain."[74] After learning of a smaller than originally anticipated military force, Wayne had to turn to recruiting local Kentucky citizens with the help of Kentucky Governor, Isaac Shelby. Although Wayne was able to successfully add Kentucky citizens to the Legion, there were still fewer than expected and many joined too late to have a significant impact.[74] Nelson goes on to write about the ineffectiveness of the Kentucky troops during the Northwest Indian War, "Once the Kentucky soldiers reached Wayne's winter head quarters, moreover, they did not cover themselves with glory. The commander, knowing that the troops were restless and murmuring about returning to their home state, suggested to Scott in late October that the Kentucky Mounted Volunteers be detached for a 'desultory expedition against the Indian Villages at Au Glaize'...To Wayne's utter disgust, one-third of Scott's men — through no fault of Scott — simply decamped for home in mid November without order."[74]

On December 24, 1793, Wayne dispatched a force to Ohio to establish Fort Recovery at the location of St. Clair's defeat as a base of operations.[71] Friendly Native Americans helped Wayne recover a cannon that had been buried nearby by the attackers, with its redeployment at the fort.[71] The fort became a magnet for military skirmishes in the summer of 1794, with an attack led by Miami chief Little Turtle failing after two days and resulting in Blue Jacket becoming war leader.[71] In response, the British built Fort Miami to block Wayne's advance and to protect Fort Lernoult in Detroit. Wayne's army continued north, building strategically defensive forts ahead of the main force. British officer Alexander McKee provided strategic battle advice to the western confederacy beforehand.[75]

On August 3, 1794, a tree fell on Wayne's tent at Fort Adams in northern Mercer County. He was knocked unconscious, but he recovered sufficiently to resume the march the next day to the newly built Fort Defiance on August 8, 1794.[71][76] After observing Wayne's activities for two years, Little Turtle declared that Wayne was "the Chief that does not sleep" and advised fellow Indians to answer calls for peace, though British agents and Blue Jacket were opposed.[71] On August 20, 1794, Wayne mounted an assault on the Indian confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near modern Maumee, Ohio, which was a decisive victory for the U.S. forces, effectively ending the war. It was later discovered that a British company under Lieutenant Colonel William Caldwell had dressed as Native Americans and participated in the battle.[77] Following the battle, Wayne used Fort Defiance as a base of operations, ordering his troops to destroy all Native American crops, homes and villages within a radius of 50 miles (80 km) around the fort.[15][71][78][79] With each Miami village that Wayne's troops approached, the Americans would consume what crops they could and destroy what was not used.[79] During the campaign, Wayne would go on to lead his troops to destroy the fields and homes of thousands of Native Americans as winter approached, using scorched earth tactics as one of his main strategies.[8][18][80][6] Admiring his scorched earth strategy, Wayne would write "their future prospects must naturally be gloomy & unpleasant".[79]

Native American troops attempted to find refuge at the British Fort Miami, though they were locked out.[8] Wayne then used Fort Deposit as a base of operations because of its proximity to Fort Miami and encamped for three days in sight of Fort Miami. Wayne attempted to provoke the fort's commander, Major William Campbell, by destroying McKee's post as well as Native American crops and villages within sight of Fort Miami before withdrawing.[81] When Campbell asked the meaning of the encampment, Wayne replied that the answer had already been given by the sound of their muskets. The next day, Wayne rode alone to Fort Miami and slowly conducted an inspection of the fort's exterior walls. The British garrison debated whether to engage Wayne, but in the absence of orders and with Britain already being at war with France, Campbell declined to fire the first shot at the United States.[82] Neither Campbell nor Wayne was willing to be the one to start a second war, and the Legion finally departed for Fort Recovery.

Wayne planned for another large battle against the Native Americans and the British while the Legion was at full strength. When Wayne arrived at Kekionga unopposed on September 17, 1794, he razed the Miami capital and then selected it as the site for the new Fort Wayne.[71][83] Wayne wanted a strong fort, capable of withstanding a possible attack by the British from Fort Detroit. Fort Wayne was finished by October 17 and was capable of withstanding 24-pound cannon. Although the Native Americans did not re-form into a large army, small bands continued to harass the Legion's perimeter, scouts, and supply trains.[84]

Wayne then negotiated the Treaty of Greenville between the tribal confederacy — which had experienced a difficult winter – and the United States, which was signed on August 3, 1795. The U.S. stated the land was already ceded to the French or British in previous wars. The treaty gave most of Ohio to the United States and cleared the way for the state to enter the Union in 1803. At the meetings, Wayne promised the land of "Indiana", the remaining land to the west, to remain Indian forever.[65] Wayne read portions of the Paris treaty, informing them that the British were encouraging them to fight for land and forts the British already ceded to the United States.

Wayne's victory was described by the Philadelphia Aurora at the time as an "uncommon slaughter" of Native Americans[85] and is recognized as the turning point that provided the geographical and imaginative base for manifest destiny.[86] In the subsequent decades, settlers would continue pushing natives further westward, with the Miami people later saying that fewer than one hundred adults survived twenty years after the treaty.[65][87]

Betrayal by Wilkinson

When picking a general to lead the Legion of the United States, President Washington considered a few options, most notably Wayne and James Wilkinson.[88] When thinking of his choices, Washington found Wayne to be, "more active and enterprising than Judicious and cautious," and Wilkinson to be lacking experience, "as he was but a short time in the Service."[70] Throughout the campaign, Wayne's second in command, General James Wilkinson, secretly tried to undermine him. Wilkinson wrote anonymous negative letters to local newspapers about Wayne and spent years writing negative letters to politicians in Washington, D.C. Wayne was unaware as Wilkinson was recorded as being extremely polite to Wayne in person. Wilkinson was also a Spanish spy at the time and even served as an officer.[89] In December 1794, Wilkinson secretly instructed suppliers to delay rations and send just enough to keep the army alive in hopes of preventing progress.[40] Secretary of War Henry Knox eventually alerted Wayne about Wilkinson, and Wayne began an investigation. Eventually, Spanish couriers carrying payments for Wilkinson were intercepted. Wayne's suspicions were confirmed, and he attempted to court-martial Wilkinson for his treachery. However, Wayne developed a stomach ulcer and died on December 15, 1796; there was no court-martial. Instead Wilkinson began his first tenure as Senior Officer of the Army, which lasted for about a year and a half. He continued to pass on intelligence to the Spanish in return for large sums in gold.[90]

Death and legacy

Wayne died during a return trip to Pennsylvania from a military post in Detroit. It has been speculated but never proven that Wilkinson had him assassinated. Wilkinson benefited from his death and was made commander.[91][92] Wayne was buried at Fort Presque Isle, where the modern Wayne Blockhouse stands. His son, Isaac Wayne, disinterred the body in 1809 and had the corpse boiled to remove the remaining flesh from the bones.[93] He then placed the bones into two saddlebags and relocated them to the family plot in the graveyard of St. David's Episcopal Church in Wayne, Pennsylvania.[94] The other remains were reburied but were rediscovered in 1878, giving Wayne two known grave sites.[93]

Wayne is not recognized as a strategist and is primarily seen as a reckless battle tactician.[9][10] He was considered impulsive, bad-tempered and overly aggressive as a military leader and advocated the tactics of Julius Caesar and Maurice de Saxe.[15][58][9][10][95] President Theodore Roosevelt would later praise Wayne as America's best fighting general.[96] He was also recognized for his grandiose and luxurious tendencies.[9][10] Contemporary leaders described Wayne in various ways; fellow officer Henry Lee III would say that Wayne "acquired strength from indulgence".[10]

More recently Wayne's legacy has been criticized due to his actions against Native Americans. During the Northwest Indian War, Wayne's military leadership led to the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans in the Ohio Valley.[7][8][6] He was recognized as being racist,[97] with Rob Harper, a historian and professor at University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, describing Wayne as holding beliefs of "racial and cultural chauvinism".[18] Wayne's victory during the Northwest Indian War set a precedent for the treatment of Native Americans by the federal government of the United States.[63][97] According to Indian Country Today, "It was General Mad Anthony Wayne who led the first wave" of Indian removal in the United States, writing that the Miami people "maintain that celebrating Wayne glosses over and ignores his role in the genocide of Native Americans".[98]

At a February 2019 city council meeting in Fort Wayne, Indiana, its members voted to approve Anthony Wayne Day by a vote of 6-3 with the resolution initially being proposed by council member Jason Arp. Of the nine council members of the time, seven were republicans and two were democrats. The two democrats and one more traditional republican voted against the creation of Anthony Wayne Day.[99] The approval was criticized by City Councilman Glynn Hines, who stated Wayne's actions were part of a "genocide of Native Americans," and many local citizens took to social media to express their thoughts.[99][98][100] The local press also covered the polarizing debate of Anthony Wayne Day, with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Charlie Savage writing, "An early public sign of dissent over the city’s creation of Wayne Day appeared in the March 8 issue of the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, the morning newspaper where I worked as a clerk in high school, and got my start as a summer reporting intern in college. It published a reader letter calling Arp’s account of history a 'victor’s version' and scorning his claim that opposing Wayne Day somehow made Hines unpatriotic."[99] During the 2019 council discussions in Fort Wayne, passages from Unlikely General by Mary Stockwell were used by members supporting Wayne, though Harper would describe Stockwell's book as sympathetic towards Wayne, concluding that, "the book's blind spots and errors make it a perilous instrument for correcting the historical record."[18] With the Miami tribe learning of the creation of Anthony Wayne Day and maintaining a strong connection with Fort Wayne, Indiana as part of their ancestral homeland, they objected to many of the facts put forward by Arp and his supporters to champion Wayne as a foundational figure in American history. Savage writes of the Miami's actions, "In a show of respect for Fort Wayne’s own sovereignty, the tribal council came to a decision: It would object to the resolution’s historical errors and omissions, but not to the honoring of Wayne himself, though they privately opposed that, too."[99] With the republicans losing two seats on the city council during the 2020 election, the future of Anthony Wayne Day is unclear with many other cultural issues emerging during the Covid-19 pandemic as well.

In addition to the destruction and death he caused against the Native Americans, Wayne is remembered for a variety of other faults. First, his open relationships with other women, who were sometimes also married, led to him and wife to become estranged.[22][18] In later years, his wife and children would go on to live in Pennsylvania with Wayne moving to Georgia to run plantations.[51][50] Second, Wayne accepted the institution of slavery and also used slaves in an attempt to enrich himself on his plantations. While his plantations would prove unsuccessful, Wayne viewed his slaves as property and would go on to sell them.[46][48] Third, Wayne and his campaign manager engaged in electoral fraud while Wayne was running for Congress. Congress would then go on to remove Wayne from office.[24][54]

On March 5, 1792, the Third United States Infantry was established to protect the borders of the newly formed United States. On November 1, 1796, it became the Third Regiment of Infantry, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Gaither. Until 1800, the Third Regiment protected the Northwest Territory and played a pivotal role in helping Wayne win the Northwest Indian war.[101] Today the Third Regiment is best known for its role in the changing-of-the-guard ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arlington National Cemetery.[99][101]

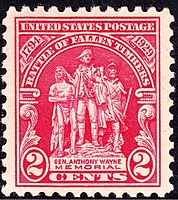

Memorials

The door in Senate room 128 features a 19th-century fresco painting by Constantino Brumidi named "Storming at Stonypoint, General Wayne wounded in the head carried to the fort".[102] On September 14, 1929, the U.S. Post Office issued a stamp honoring Wayne which commemorated the 135th anniversary of the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The post office issued a series of stamps often referred to as the "Two Cent Reds" by collectors, most of them issued to commemorate the 150th anniversaries of the many events that occurred during the American Revolution. The stamp shows Bruce Saville's Battle of Fallen Timbers Monument.

Descendants and relatives

Wayne's notable relatives and descendants include:

- Isaac Wayne (1772–1852), Wayne's son, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.[103]

- Captain William Evans Wayne (1828-1901) fought in the Civil War for the Union.[104]

- Isaac Wayne Van Leer (1846-1861) enlisted for the Union during the Civil War at age 15 and was documented in several publications for his patriotism.[105]

- Blake Wayne Van Leer (1926-1997), a prominent commander and captain in the U.S. Navy and led Seabee program, the nuclear research and power unit at McMurdo Station during Operation Deep Freeze.[106][107]

Gallery

The Storming of Stony Point, 1779 by Constantino Brumidi (1871) in room S-128 of the United States Capitol

Battle of Fallen Timbers, commemorative issue of 1928, 2¢

His home, Waynesborough in Paoli, Pennsylvania

Anthony Wayne Bridge (Toledo, Ohio)

Keystone Marker in Wayne, Pennsylvania, named for General Wayne

Wayne County Building (Detroit, Michigan) pediment

Wayne State University. Detroit, Michigan, Maccabees Building

See also

Notes

- ^ Boatner, Mark M. (2006). v Encyclopedia of the American Revolution: Library of Military History. Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 670.

- ^ Washington, George (July 16, 1799). [link.gale.com/apps/doc/EJ2153000098/UHIC?u=vol_s22s&sid=bookmark-UHIC&xid=75c9f2d0. "Wayne Storms Stony Point, New York (1779)"]. Primary Source Media. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Aimone, Alan Conrad (2005). "New York State Society of the Cincinnati: Biographies of Original Members and Other Continental Officers (review)". The Journal of Military History. 69 (1): 231–232. doi:10.1353/jmh.2005.0002. ISSN 1543-7795. S2CID 162248285.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Wayne Family. "Anthony Wayne Family Papers". Clements Library. University of Michigan. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Hixson, W. (2013). American Settler Colonialism: A History. Springer Publishing. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9781137374264.

the American approach to Indian removal: it would seek to accomplish the project humanely and through diplomacy but when Indians resisted giving up colonial space, "justice" was on the side of military aggression and ethnic cleansing. Americans mobilized for violent retribution under the command of General "Mad" Anthony Wayne, who declared his eagerness to lay siege to the "haughty and insidious enemy." ... American History texts focus on the anticlimactic Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794) but it was the scorched-earth campaign against the Indian homes and agricultural stocks that shattered the resistance.

- ^ a b Zelnik, Eran (Spring 2021). "Self-Evident Walls: Reckoning with Recent Histories of Race and Nation". Journal of the Early Republic. Philadelphia. 41 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1353/jer.2021.0000. S2CID 234183824.

In fact, recent scholarship has shown, elites too did not shy away from carrying out even more brutal campaigns against the Natives of the region when it suited their needs. ... Anthony Wayne's scorched-earth campaign in 1794 ... elites-through the federal government and the states-led and organized the military push that resulted in ethnic cleansing. ... These diverse ethnic cleansing strategies stand in stark contrast to resolution of tensions-even when they became militant-between Euro American settlers. ... Similarly, during the summer of 1794-while Anthony Wayne was burning villages and fields across the Ohio Valley-on the eastern edge of the valley, near Pittsburgh, the Whiskey Rebellion met a very different ending. Though Alexander Hamilton and President Washington wanted to make an example of the west Pennsylvania uprising and recruited an army of 13,000 troops, tensions were resolved with virtually no bloodshed.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Gary Clayton (2014). Ethnic Cleansing and the Indian: The Crime That Should Haunt America. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780806145082.

General Wayne prepared his army for combat. Plain and simple, the young United States was going to war to "cleanse" Ohio of its Indians.

- ^ a b c d Harper, Rob (June 2021). "Across the City Council Divide". Reviews in American History. Baltimore. 49 (2): 222–231. doi:10.1353/rah.2021.0023. S2CID 238033600.

[Wayne] lacked the imagination and pragmatic adaptability of a Washington or Nathanael Greene. He was a better tactician than a strategist, and a better bon vivant than a human being. He was impulsive and prone to flights of grandiosity, flavored with a heavy dose of Julius Caesar.

- ^ a b c d e Nelson, Paul David (October 1982). "Anthony Wayne: Soldier as Politician". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. University of Pennsylvania Press. 106 (4): 463–464.

Anthony Wayne is remembered in history primarily as a "proud, quick-tempered, impetuous, and even arrogant" soldier of the Revolutionary War, ... "General Wayne had a constitutional attachment to the sword," said Henry Lee of his colleague in arms, "and this cast of character had acquired strength from indulgence." ... [Wayne's] reputation as a rash, impulsive officer who acted first and thought later

- ^ Dixon, Mark E. (May 20, 2015). "What Almost Bankrupted Gen. Anthony Wayne". Main Line Today. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Harper, Rob (2021). "Across the City Council Divide". Reviews in American History. 49 (2): 222–231. doi:10.1353/rah.2021.0023. ISSN 1080-6628. S2CID 238033600.

- ^ Caust-Ellenbogen, Celia. ""Mad" Anthony Wayne". Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Nelson 1985, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Anthony Wayne". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. University of Pennsylvania Press. 32 (3): 257–301. 1908.

- ^ a b c d e "What Almost Bankrupted Gen. Anthony Wayne". Main Line Today. May 20, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ Labaree, pp. 345-350.

- ^ a b c d e f Harper, Rob (June 2021). "Across the City Council Divide". Reviews in American History. Baltimore. 49 (2): 222–231. doi:10.1353/rah.2021.0023. S2CID 238033600.

- ^ Nelson 1985, pp. 4–5, 208.

- ^ "Anthony and Mary (Penrose) Wayne Family Bible". ACPL Genealogy Center. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ HistoryNet Staff (July 10, 2019). "Book Review: Unlikely General". HistoryNet. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "1780 Chester County Slave Register". Chester County, Pennsylvania. July 28, 2020.

- ^ Nelson, Paul David (1982). "Anthony Wayne: Soldier as Politician". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. American National Biography Online: 463–481.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Nelson, Paul David (October 1982). "Anthony Wayne: Soldier as Politician". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. University of Pennsylvania Press. 106 (4): 463–481.

- ^ Nelson 1985, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Savage, Charlie (July 31, 2020). "When the Culture Wars Hit Fort Wayne". POLITICO. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Nelson 1985, p. 52.

- ^ Nelson 1985, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Nelson 1985, p. 60.

- ^ Lancaster, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Boatner, Mark M. (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- ^ a b c d e Pennypacker, Samuel (1908). "Anthony Wayne". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 32 (3): 257–301. JSTOR 20085434 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Boatner, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Wright, Robert K. Jr. (2006). Mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line. Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 772–775.

- ^ Lancaster, pp. 319–322.

- ^ "The Legacy of Anthony Wayne". Yale University Press Blog. May 8, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Nicknaming of General "Mad" Anthony Wayne". Journal of the American Revolution. May 3, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Harper, Rob (June 2021). "Across the City Council Divide". Reviews in American History. Baltimore. 49 (2): 222–231. doi:10.1353/rah.2021.0023. S2CID 238033600.

Early on, he captured a large group of Creeks, treated them well, and then sent them home, hoping they would spread goodwill toward the United States. But months of brutal skirmishing compounded by the general's bad temper, mood swings, and depression, wore away at Wayne's openness to Indian friendship. In July, he put thirty Creek prisoners to death.

- ^ a b Nelson 1985, p. 4: "As time wore on, therefore, General Wayne expressed views that were more and more at variance with his earlier, more democratic positions on how government, society, and they army ought to be organized and who should dominate these institutions. In short, ... he advocated until the end of his life, that a strong central government ought to be instituted by, and maintained in the interests of, the propertied and "aristocratick" elements of the nation. ... he concluded that the same officer corps of the army ought likewise be recruited from these same elites. Since he was a member of that small social group which in his scheme would run things, and since he might be helped personally by securing a "place" in such a structuring of government, it is not surprising that he became a Federalist"

- ^ a b Stockwell, Mary (2018). Unlikely General. Yale University Press. pp. 88–236.

- ^ "Founders Online: May [1791]". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Rogers, George C. Jr. (April 1988). "A Social Portrait of the South at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century". Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. American Antiquarian Society. 98, Part 1: 35–49.

- ^ a b c Nelson 1985, pp. 187–208.

- ^ a b c d "RICHMOND OAKGROVE PLANTATION: Part II". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. Georgia Historical Society. 24 (2): 124–144. June 1940.

- ^ "Anthony Wayne family papers 1681-1913". William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Harper, Rob (June 2021). "Across the City Council Divide". Reviews in American History. Baltimore. 49 (2): 222–231. doi:10.1353/rah.2021.0023. S2CID 238033600.

Stockwell reveals almost nothing about Wayne's investments in slavery. She briefly mentions Wayne buying new uniforms for himself and "his servant Caesar" (p. 224), but leaves it to the reader to imagine the general naming an enslaved man after his favorite Roman hero. An image of a broadside advertising the sale of his Georgia properties mentions the availability of "a Gang of Fifty Country Born and Seasoned Negroes," but Stockwell's text mentions only that the broadside listed "the many assets of the place" (pp. 238, 237). Elsewhere she refers to "slaves taken by the British army" (p. 250): a dismissive way to describe people who had freed themselves from bondage and found refuge with the enemy-of-their-enemy. Throughout the book enslaved people appear rarely, and only as passive property (as Wayne himself may have seen them).

- ^ Nelson 1985, pp. 4–5, 187–208.

- ^ a b Procknow, Gene (June 20, 2018). "Unlikely General: Mad Anthony Wayne and the Battle for America". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

Wayne’s ownership of slaves, on the other hand, is the one aspect of Wayne’s devotion to liberty that Stockwell did not address. Similar to most other Revolutionary War generals, Wayne condoned slavery and readily purchased numerous slaves after the Revolution to work on his new plantation given to him by the state of Georgia for his service in chasing the British from the state.

- ^ "Mulberry Grove from the Revolution to the Present Time". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. Georgia Historical Society. 23 (4): 315–336. December 1939.

- ^ a b c "Richmond Oakgrove Plantation: Part II". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. Georgia Historical Society. 24 (2): 124–144. June 1940.

- ^ a b "RICHMOND OAKGROVE PLANTATION: Part II". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. Georgia Historical Society. 24 (2): 124–144. June 1940.

- ^ "Wayne, Anthony, (1745–1796)". bioguide.congress.gov.

- ^ Gumbel, Andrew (Winter 2008). "Election Fraud and the Myths of American Democracy". Social Research. 75 (4): 1109–1134. doi:10.1353/sor.2008.0004.

- ^ a b c Urwin, Gregory J W (Spring 2020). "Unlikely General: "Mad" Anthony Wayne and the Battle for America". Journal of the Early Republic. 40 (1): 138–140. doi:10.1353/jer.2020.0009. S2CID 213615655.

- ^ United States Congressional Elections, 1788–1997: The Official Results confirms the seat was declared vacant on March 21, 1792.

- ^ a b "TEHS - Quarterly Archives". tehistory.org.

- ^ Nelson 1985, pp. 4–5, 208, 187–208.

- ^ a b "Wayne, General Anthony | Detroit Historical Society". detroithistorical.org.

- ^ Landon Y. Jones (2005). William Clark and the Shaping of the West. p. 41. ISBN 9781429945363.

- ^ Calloway, Colin G. (June 9, 2015). "The Biggest Forgotten American Indian Victory". What It Means to be American. The Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ "Roles of Native Americans during the Revolution". American Battlefield Trust. January 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Horsman, Reginald (September 1, 1962). "The British Indian Department and the Resistance to General Anthony Wayne, 1793–1795". Journal of American History. 49 (2): 269–290. doi:10.2307/1888630. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 1888630.

- ^ a b c Cayton, Andrew R L. (June 1992). ""Separate Interests" and the Nation-State: The Washington Administration and the Origins of Regionalism in the Trans-Appalachian West". The Journal of American History. 79 (1): 39–67. doi:10.2307/2078467. JSTOR 2078467.

- ^ Harper, Rob (June 2021). "Across the City Council Divide". Reviews in American History. Baltimore. 49 (2): 222–231. doi:10.1353/rah.2021.0023. S2CID 238033600.

[Wayne] headed west a burnt-out shell of a man who had found success only on the battlefield and who was predisposed to view Native people as inveterate enemies.

- ^ a b c Savage, Charlie (July 31, 2020). "When the Culture Wars Hit Fort Wayne". Politico. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Horsman, Reginald (September 1, 1962). "The British Indian Department and the Resistance to General Anthony Wayne, 1793–1795". Journal of American History. 49 (2): 269–290. doi:10.2307/1888630. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 1888630.

- ^ DuVal, Kathleen (May 15, 2018). "'Unlikely General' Review: He Opened the Way West". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Deloria, Philip (November 2, 2020). "Defiance". The New Yorker. Vol. XCVI, no. 34.

After the defeats, George Washington tripled the size of the Army and committed five-sixths of the federal budget to subduing the Western Indians. Anthony Wayne’s victory at Fallen Timbers was made possible because the Americans, out of necessity, threw everything they had at the Indian alliance.

- ^ a b c d Brooke, John (1895). "Anthony Wayne: His Campaign against the Indians of the Northwest". University of Pennsylvania Press. 78 (3): 387–396. JSTOR 20085650 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b D., Gaff, Alan (2008). Bayonets in the wilderness : Anthony Wayne's legion in the Old Northwest. Univ. of Oklahoma Press. pp. 22–24. OCLC 914618152.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tucker, Spencer (2013). Almanac of American Military History, Volume 1. ABC-Clio. pp. 412–427. ISBN 9781598845303.

- ^ Quintin, Brandon (June 24, 2019). "Assessment of the Legion as the Ideal Small Wars Force Structure". Divergent Options. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ a b Stockwell, Mary (2018). Unlikely General. Yale University Press. pp. 56–184.

- ^ a b c Nelson, Paul David (1986). ""Mad" Anthony Wayne and the Kentuckians of the 1790s". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 84 (1): 1–17. JSTOR 23381138 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Sword 2003, p. 296.

- ^ Carter, p. 133.

- ^ Sword 2003, p. 298.

- ^ "Defiance, Ohio - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bergmann, William H (Spring 2008). "A "Commercial View of This Unfortunate War": Economic Roots of an American National State in the Ohio Valley, 1775-1795". Early American Studies. 6 (1): 137–164. doi:10.1353/eam.2008.0000. S2CID 144686624.

- ^ Zelnik, Eran (Spring 2021). "Self-Evident Walls: Reckoning with Recent Histories of Race and Nation". Journal of the Early Republic. 41 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1353/jer.2021.0000. S2CID 234183824.

- ^ "Defiance, Ohio - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Hogeland, pp. 350–351.

- ^ Poinsatte, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Nelson 1985, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Riordan, Liam (Summer 2011). ""O Dear, What Can the Matter Be?": The Urban Early Republic and the Politics of Popular Song in Benjamin Carr's Federal Overture". Journal of the Early Republic. 31 (2): 179–227. doi:10.1353/jer.2011.0026. S2CID 145801731.

- ^ Shalev, Eran (Summer 2021). ""This Natural Defect of Apprehension": Native Americans and the Politics of Time in the Young United States". European Journal of American Studies. 16 (2). doi:10.4000/ejas.16983. S2CID 237798370.

- ^ Pember, Mary Annette. "Celebrating (not) Mad Wayne Day". Indian Country Today. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Landon (2004). William Clark and the Shaping of the West. Hill and Wang.

- ^ "This Day in History: The Secret Plot Against General Mad Anthony Wayne". Taraross. January 25, 2019.

- ^ Nelson, 1999

- ^ Harrington, Hugh T. (August 20, 2013). "Was General Anthony Wayne Murdered?". Journal of the American Revolution.

- ^ "Why I Believe Meriwether Lewis Was Assassinated | History News Network". historynewsnetwork.org.

- ^ a b "Wayne Buried in Two Places". Paoli Battlefield. Independence Hall Association. Retrieved October 16, 2019 – via ushistory.org.

- ^ Hugh T. Harrington and Lisa A. Ennis. "Mad" Anthony Wayne: His Body Did Not Rest in Peace, citing History of Erie County, Pennsylvania, vol. 1. pp. 211–212. Warner, Beers & Co., Chicago. 1884.

- ^ Procknow, Gene (June 20, 2018). "Unlikely General: Mad Anthony Wayne and the Battle for America". Journal of the American Revolution.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore; Lodge, Henry Cabot. "Hero Tales from American History - The Storming of Stony Point". Together We Teach. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Ariail Reed, Isaac (2017). "Chains of Power and Their Representation". Sociological Theory. 35 (2): 90.

Having reorganized the flailing U.S. Army into legions and achieved a massive and brutally violent victory, Wayne was the walking embodiment of a new American populism—pragmatic, self-confident, and racist.

- ^ a b Pember, Mary Annette. "Celebrating (not) Mad Wayne Day". Indian Country Today. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Savage, Charlie (July 21, 2020). "When the Culture Wars Hit Fort Wayne". Politico. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Tran, Louie (March 2, 2019). "'If it wasn't for Anthony Wayne, there may not be a United States of America'; City Council officials share the importance of Anthony Wayne Day". WPTA. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ a b "Third Regiment of Infantry | The Army of the US Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief | U.S. Army Center of Military History". history.army.mil. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ "8 "Gems of the Capitol"". Constantino Brumidi: Artist of the Capitol (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1998. pp. 106, 109. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ "Biography of General Anthony Wayne". www.ushistory.org.

- ^ ""Mad" Anthony Wayne | Historical Society of Pennsylvania". hsp.org.

- ^ Smith Futhey, J. (2007). "History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical". History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical. pp. 752–753. ISBN 9780788443879.

- ^ "Wayne Family". www.vanleerarchives.org.

- ^ "TEHS - Quarterly Archives". tehistory.org.

References

- Allen, William B. (1872). A History of Kentucky: Embracing Gleanings, Reminiscences, Antiquities, Natural Curiosities, Statistics, and Biographical Sketches of Pioneers, Soldiers, Jurists, Lawyers, Statesmen, Divines, Mechanics, Farmers, Merchants, and Other Leading Men, of All Occupations and Pursuits. Bradley & Gilbert. pp. 46–47. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Boatner, Mark M., III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Carter, Harvey Lewis (1987). The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01318-2.

- Dubin, Michael J (1998). United States Congressional Elections, 1788–1997: The Official Results of the Elections of the 1st through 105th Congresses. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company. ISBN 0-7864-0283-0.

- Hogeland, William (2017). Autumn of the Black Snake: the creation of the U.S. Army and the invasion that opened the West. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374107345. LCCN 2016052193.

- Knopf, Richard C., ed. (1960). Anthony Wayne: A Name in Arms. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822975342.

- Labaree, Leonard W., ed. (1968). The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Vol. 12. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

- Lancaster, Bruce (1971). The American Revolution. New York: American Heritage Books. ISBN 0-618-12739-9.

- Nelson, Paul David (1985). Anthony Wayne. Soldier of the Early Republic. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-30751-1.

- Nelson, Paul David. "Wilkinson, James (1757–28 December 1825)" American National Biography (1999).

- Pleasants, Henry; Delaware County Historical Society (1907). History of Old St. David's Church Radnor, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. John C Winston Co. p. 206.

- Poinsatte, Charles (1976). Outpost in the Wilderness: Fort Wayne, 1706-1828. Allen County, Fort Wayne Historical Society. ISBN 3337364691.

- Wayne, Isaac (1829). Biographical Memoir of Major General Anthony Wayne. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Casket No. 5. pp. 190–203.

- Sword, Wiley (2003) [1985]. President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2488-9.

External links

- Anthony Wayne and the Battle of Fallen Timbers from The Army Historical Foundation

- General Anthony Wayne

- Anthony Wayne family papers. William L. Clements Library.

- National Park Service Museum Collection: American Revolutionary War Exhibit, Wayne portrait & bio

- Maumee Valley Heritage Corridor

- Anthony Wayne – The Man Buried in Two Places

- CS1 errors: URL

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Articles with short description

- Use mdy dates from January 2015

- Commons category link is defined as the pagename

- AC with 0 elements

- 1745 births

- 1796 deaths

- American slave owners

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American people of the Northwest Indian War

- Burials at St. David's Episcopal Church (Radnor, Pennsylvania)

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Continental Army generals

- Continental Army officers from Pennsylvania

- History of Fort Wayne, Indiana

- Members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Georgia (U.S. state)

- People from Chester County, Pennsylvania

- People from Paoli, Pennsylvania

- History of Pennsylvania

- People of colonial Pennsylvania

- People of Pennsylvania in the American Revolution

- United States Army generals

- University of Pennsylvania alumni

- Commanding Generals of the United States Army

- 18th-century American politicians

- Members of the United States House of Representatives removed by contest