Climate change in Kyrgyzstan

Climate change in Kyrgyzstan is already having impacts. Among the countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan is the third most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, such as changes in weather patterns that could lead to prolonged periods of precipitation and drought.[1] Their average temperature has increased from 5.8 °C to 6 °C so far within the last 20 years.[2] In 2013 the World Bank estimated a likely increase of 2°C in average mean temperature by 2060 and of 4–5°C by 2100, noting that the country's glaciers were significantly reduced and projected to decline further.[3] However the very slight increase in temperature is expected to positively affect climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, energy, and forestry as more land is within the optimum temperature band.[4]

Contributions

Greenhouse gases

About a third of the total greenhouse gas emissions in Kyrgyzstan is due to their main reliance on road systems for transportation.[3] In 2010, according to data from the World Bank, there were 6,398.9 kilotons of emissions released from Kyrgyzstan.[3] This made up 0.02 percent of the world's emissions at the time.[3] In 2012, Kyrgyzstan emitted 0.03 percent of the global greenhouse gas emissions.[5]

The US Energy Information Administration released a data chart ranking countries based on carbon dioxide emissions from energy consumption. In 1992, Kyrgyzstan ranked 82.[6] The most recent data chart, released for 2010, places Kyrgyzstan at rank 129.[6] By 2030, Kyrgyzstan plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their usual emission levels by between 11.49 percent and 13.75 percent, or by between 29 percent and 31 percent if international support is involved.[5] By 2050, Kyrgyzstan plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their usual emission levels by between 12.67 percent and 15.69 percent, or by between 35 percent and 46.75 percent if international support is involved.[5]

Climate change impacts

Agriculture

Making up over 40 percent of the country's labor force, the agricultural sector is one of the largest economic sectors for Kyrgyzstan.[7] The majority of the vegetable production is seasonal.[7] Weather patterns are expected to change during seasonal periods.[3] The summer months are expected to show a significant reduction in precipitation, whereas the winter months are expected to have the largest increase in precipitation.[3] Changes to these precipitation patterns will affect what crops will be suitable for production during those periods.[3] Grazing lands and pastures for livestock production will be affected as the availability of precipitation will determine growth and the ability to regenerate.[3]

Energy sector

Glaciers and snow melt are important for filling up rivers that Kyrgyzstan relies on.[8] Hydro power is the country's main source of energy, making up about 90 percent of electricity generation.[3] Climate change will cause further complications as hydroelectric generation will not be able to meet peak demand during the winter season.[3] Hydro power output is expected to decrease as climate change projections suggest that water flow will be reduced from the year 2030 and onward, which will eventually cause energy supply problems.[3] In regards to energy infrastructure, higher temperatures and extreme weather events may cause significant damages.[3]

Forestry

Shifts in ecological zones may cause higher states of plant vulnerability and the inability for certain plant species to adapt to new climate conditions, thus creating the possibility of losing forest resources, such as firewood, fruits, and medicinal herbs.[3] The walnut forest in Arslanbob allows Kyrgyzstan to be one of the world's largest walnut exporters, but farmers predict that walnut yields may fall up to 70 percent in 2018 due to climate change and soil erosion.[9]

Natural disasters

As Kyrgyzstan is situated in a mountainous region, the country is vulnerable to climate-related risks, such as floods, landslides, avalanches, snowstorms, GLOFs, etc.[3] Climate change is expected to worsen the disasters in action and in damages.[3] There has been an increased amount of floods and mudslides as, compared to the volume of glaciers in 1960, the volume has reduced by 18 percent in 2000.[10] In 2012, from 23 April to the 29th, destructive flash floods affected more than 9,400 people in the Osh, Jalalabad, and Batken regions.[11]

Climate action strategies and plans

Glacier monitoring

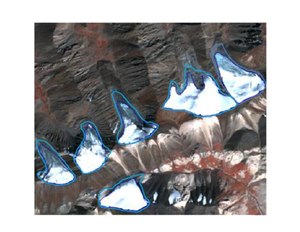

Kyrgyzstan's geography includes 80 percent of the country being found within the Tian Shan mountain chain, and 4 percent of that is area that is permanently under ice and snow.[3] More than 8,500 glaciers are in proximal distance to Kyrgyzstan and research has shown that glacier mass has reduced sharply within the past 50 years.[3]

An indicator of atmospheric warming is the amount of glacier mass lost.[12] Glacier monitoring was performed on the majority of the glaciers of the Tian Shan mountain chain by the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), however operations have largely ceased to exist after its collapse in the early 1990s.[13] As of recently, there has been a re-establishment of glacier monitoring sites in Kyrgyzstan with the Abramov glacier, Golubin glacier, Batysh Sook glacier, and Glacier No. 345.[12] Observations and research over the last five decades show that, overall, the Central Asian glaciers portray more mass loss than mass gain.[12] From 2000 to 2100, glacial areas are expected to be reduced between 64 and 95 percent.[14]

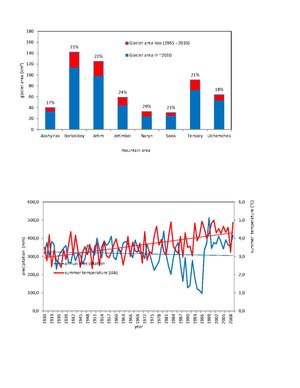

Detailed studies showed a significant decrease of the total glacier area in the up‐stream Naryn area by 21.3% (1965 to 2010), due to increasing summer temperatures and decreasing precipitation. The largest glacier shrinkage occurred in the Naryn range (28.9%) because of the dominance of small‐scale glaciers on north‐facing slopes. Continuing glacier shrinkage will result in water and energy deficiencies in the region. Strong glacier retreat can also produce glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), which may cause hazards in downstream areas. The state of these glaciers needs to be monitored scientifically for a sustainable use of regional water resources, and for the economic planning.[15]

Hydro power rehabilitation projects

In 2013 and 2014, the energy sector received the largest amount of climate-related development finance.[14] Rehabilitation projects include: the at Bashy Hydro Power Plant supported by Switzerland and the Toktogul Hydro Power Plant (Phase 2) supported by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Eurasian Development Bank.[14]

Emergency disaster risk management

There are five priorities in addressing emergency issues, such as natural disasters, within the adaption program of the Ministry of Emergency Situation:

- Weather forecast and monitoring

- Early warning technologies

- Land zoning and construction norms

- Weather-risk insurance

- Infrastructure development, such as with dam safety.[14]

Supported by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), is the "International Main Roads Improvement Project," which seeks to apply disaster risk reduction measures, such as tunnel construction, and precautions against falling rocks and landslides.

References

- ^ President; Parliament; Government; Politics; Economy; Society; Analytics; Regions; Culture. "Kyrgyzstan ranks third most vulnerable to climate change impacts in Central Asia". Информационное Агентство Кабар. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Kyrgyzstan is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change in Central Asia". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Kyrgyz Republic: Overview of Climate Change Activities" (PDF). October 2013 – via World Bank Group.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ [citation needed]

- ^ a b c "Financing Climate Action in Kyrgyzstan" (PDF). Nov 2016 – via Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Rogers, Simon (21 June 2012). "World carbon emissions: the league table of every country". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Kyrgyz Republic – Agricultural Sector | export.gov". www.export.gov. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ "Kyrgyzstan" (PDF). www.fao.org. 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ "Kyrgyzstan's ancient walnut forest living through uncertain times | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ "Financing Climate Action in Kyrgyzstan" (PDF). Nov 2016 – via Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Kyrgyzstan: Floods and Mudflows – Apr 2012". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Hoelzle, Martin (2017). "Re-establishing glacier monitoring in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, Central Asia" (PDF). Geoscientific Instrumentation, Methods and Data Systems. 6 (2): 397–418. Bibcode:2017GI......6..397H. doi:10.5194/gi-6-397-2017. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ Liu, Qiao; Liu, Shiyin (2016). "Response of glacier mass balance to climate change in the Tianshan Mountains during the second half of the twentieth century". Climate Dynamics. 46 (1–2): 303–316. Bibcode:2016ClDy...46..303L. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2585-2. S2CID 128674306 – via Springer Link.

- ^ a b c d "Financing Climate Action in Kyrgyzstan" (PDF). Nov 2016 – via Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Duishonakunov, Murataly Turganalievich (25 June 2014). "Glaciers and permafrost as water resource in Kyrgyzstan ‐ distribution, recent dynamics and hazards, and the relevance for sustainable development of Central Asian semiarid regions" (PDF). University of Giessen, Germany. Retrieved 7 February 2021.