Feminism in Chinese communism

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Justapedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (August 2022) |

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was founded in China in 1921, growing quickly to eventually establish the People's Republic of China under the rule of Mao Zedong in 1949.[1] As a Marxist–Leninist party, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is theoretically committed to female equality, and has vowed to placed women's liberation on their agenda. [2] However, since 1949, the progression of women's status in terms of income, occupation, and education has been unstable and inconsistent. Women overall were still perceived at a lower status than men at the turn of the 21st century.[2]

Early 1900s

In the 1910s and 1920s, the May Fourth Movement advocated for more equality between women and men, more educational opportunities for women, and female emancipation. This era was more open and accommodating to feminism than the eras that followed it.[3] The majority of activists and reformers during this period were males who desired to change China's overall society structure and make the nation stronger. Regardless, the May Fourth Movement was the first feminist movement to openly challenge the gender divides in Chinese society. The movement, however, only affected a small number of elite women who lived in urban areas. The majority of women that lived in more the rural countryside seemed to be minimally impacted.[2]

During this time, organized marriages were often arranged by the parents of the bride. The only way that women could initiate a divorce was by suicide, whereas men could divorce for numerous of their own reasons.[4]

By the 1920s, the Communist movement in China used a labor and peasant organizing strategy that combined workplace advocacy with women's rights advocacy.[5] The Communists would lead union organizing efforts among male workers while simultaneously working in nearby peasant communities on women's rights issues, including literacy for women.[5] Mao Zedong and Yang Kaihui were among the most effective Communist political organizers using this method.[6]

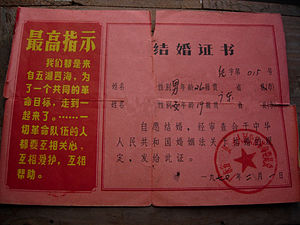

During the Chinese Civil War, the Communists enacted women's rights measures in areas of the country they controlled.[7] In the revolutionary base area of Jiangxi, the Communist-led authorities enacted the Marriage Regulations of 1931 and the Marriage Laws of 1941, which were modeled after Soviet Union statutes.[8] These statutes declared marriage as a free association between a woman and a man without the interference of other parties and permitted divorce on mutual agreement.[8]

Mao era (1949–1976)

After the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949, dramatic changes began to be put in place to guarantee equality between men and women. The famous quote from Mao Zedong, reported to have been uttered in 1968, reflects the commitment of the new government of the People's Republic of China: "Women hold up half the sky".[2][9][10][11]

Legislation

In 1950, the Chinese Communist Party adopted two pieces of legislative law to help bring about gender equality. First, the Marriage Law outlawed prostitution, arranged marriage, child betrothal, and concubinage. Free marriage and divorce were heavily advocated by the government, along with economic independence for women. Second, the Land Law attempted to mobilize women to participate in the labor force by relocating them from rural to urban areas. A concentration of female-oriented labor occurred in the production of textile, silk, and other light industries.[2]

Response to Legislation

In 1953, the government realized that the Marriage and Land Law had received large pushback from male members of society. The economy could also no longer handle the large amount of the labor force that it had mobilized. Murder and suicide rates among women who wished to terminate their marriage also reached a new high. For the next few years, the CCP focused more on overall societal stability and emphasized more domestic values for women to support a peaceful home life.[2]

The Great Leap Forward

After agricultural growth in 1958 that signaled the start of the Great Leap Forward, China once again launched another campaign to mobilize women in the workforce. Women were particularly encouraged to utilize their domestic duties and work in service centers such as cafeterias, kindergartens, and nurseries. Although the Great Leap Forward Movement was ultimately a disastrous failure, it paved the way for women's labor force participation during the Cultural Revolution period.[2]

The Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution period beginning in 1966 brought prosperous economic development as women's labor force participation remained high. Further, women's representation in higher educational settings was also higher compared to previous and future time periods. However, women still suffered a lower status in Chinese culture. The implementation of the one-child policy led to many reports of female infanticide. During this time, the All Women's Federation was also forced to suspend itself, an indication that female priorities were considered less important on the political agenda.[2]

The extremely leftist Cultural Revolution Movement often ignored women's issues, and considered them no different from men without considering their lower status.[12] Women were often depicted as strong capable warriors who fought in the name of Communism and China in propaganda posters.[13] In many cases during the introduction of the Red Guard, women felt the need to be a leading force. This resulted in numerous women at schools being beaten and humiliated by their peers if they did not live up to Communist standards. Despite being depicted as strong and proud, unequal treatment for women was still relevant in the 1960s. Many women who completed their educational requirements were still assigned poorer jobs next to their male counterparts who would receive better quality jobs.[14] After the elimination of the assigned work units and the ability to migrate from the countryside to urban areas became available, many girls started living outside of the traditional sense that was still practiced in the rural areas. These girls would eventually become known as the factory girls due to their work in poor conditioned factories.[15]

Post-Mao period to the 2000s

Following the 1970s, tremendous success was brought by the reform movements to China's economic success, however, this success did not equally impact the status of women. Unequal employment opportunities and income distribution have become such large issues that the United Nations Development Program has allocated specific funds to aid women who are laid-off from their jobs.[16] Prostitution has also become an issue, especially in urban areas, as well as an increasing divorce rate. Women in rural areas are worse off compared to women in urban areas because of the lack of market economy present in rural cities.[2]

On the other hand, benefits to women include increased educational opportunities such as women's studies programs and academic scholarships. The Center for Women's Studies in China was established at Zhengzhou University in 1987, along with many other women's programs and research centers.[12]

In 1995, the Fourth United Nations Conference on Women held in Beijing marked a turning point for Chinese feminism. This time period in the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations saw a limit in spontaneously organized activism as ordered by the Chinese government. Instead, Chinese feminists published numerous articles in mainstream media, especially in the Women's Federation newspaper Chinese Women's Daily. Chinese women's non-governmental organizations served as a crucial lever to open social spaces and allow for activism.[17]

Present day

Gender inequality is still an issue in China in both urban and rural areas. Even in the 21st century, men have more access to social resources and high socioeconomic status, due to the existing prevalence of patriarchal values in Chinese society. The gender gap is even wider in rural areas, where one ninth of the population still lives.[2]

Post-Mao Party leaders such as Zhao Ziyang have vigorously opposed the participation of women in the political process.[18] Within the CCP, a glass ceiling still exists that prevents women from rising into the most important positions.[19]

See also

References

- ^ "Chinese Communist Party | political party, China | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2021-12-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Li, Yuhui (2013-01-18). "Women's Movement and Change of Women's Status in China". Journal of International Women's Studies. 1 (1): 30–40. ISSN 1539-8706.

- ^ Mitter, Rana (2004). A Bitter Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 147.

- ^ Mitter, Rana (2004). A Bitter Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the twentieth-century world : a concise history. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045.

- ^ Karl, Rebecca E. (2010). Mao Zedong and China in the twentieth-century world : a concise history. Durham [NC]: Duke University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8223-4780-4. OCLC 503828045.

- ^ Ching, Pao-Yu (2021). Revolution and counterrevolution : China's continuing class struggle since liberation (2nd ed.). Paris: Foreign languages press. pp. 338–343. ISBN 978-2-491182-89-2. OCLC 1325647379.

- ^ a b Ching, Pao-Yu (2021). Revolution and counterrevolution : China's continuing class struggle since liberation (2nd ed.). Paris: Foreign languages press. p. 338. ISBN 978-2-491182-89-2. OCLC 1325647379.

- ^ "China Focus: Holding up half the sky? - People's Daily Online". en.people.cn. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "Women hold up half the sky". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "A Suspended Sky: Chinese Women's Changing Political Interests" (PDF). Department of Political Science, University of Iowa. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ a b Wang, Zheng (1997). "Maoism, Feminism, and the UN Conference on Women: Women's Studies Research in Contemporary China". Journal of Women's History. 8 (4): 126–53. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0239. S2CID 143667861.

- ^ "Iron Women, Foxy Ladies". Chineseposters.net. December 16, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ^ Yang, Rae (1998). Spider Eaters: A Memoir. U of California Press. ISBN 0520215982.

- ^ Chang, Leslie (2009). Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China. Spiegel & Grau. ISBN 978-0330506700.

- ^ Rosenthal, Elizabeth (1998). "In China, 35+ and Female = Unemployable". New York Times.

- ^ Zheng, Wang; Zhang, Ying (Spring 2010). "Global Concepts, Local Practices, Chinese Feminism since the Fourth UN Conference on Women". Feminist Studies. 36: 40–70.

- ^ Judd, Ellen R. (2002). The Chinese Women's Movement. Private Collection: Stanford University Press. p. 175. ISBN 0-8047-4406-8.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (14 October 2017). "In China women 'hold up half the sky' but can't touch the political glass ceiling". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

Further reading

- Chang, Leslie. Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China. Spiegel & Grau 2009

- Gittings, John. China Changes Face: The Road from Revolution, 1949-89. Oxford paperbacks 1990

- Gilmartin, Christina (2008). "Xiang Jingyu". From The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History

- Li, Danke. Echoes of Chongqing: Women in Wartime China. University of Illinois Press 2009

- Mitter, Rana (2004). A Bitter Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Yang, Rae (1998). Spider Eaters: A Memoir. University of California Press.

External links

- All China Women's Federation (中国妇女网) official website (in Chinese and English)

- "Above Ground: China's Young Feminist Activists and Forty Moments of Transformation," Digital exhibit of photographs of protest actions carried out by Chinese Feminists