Walt Disney World

Slogan: The Most Magical Place on Earth[1] | |

| Industry | |

|---|---|

| Founded | October 1, 1971 |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | Lake Buena Vista and Bay Lake, Florida, U.S. |

Key people | Jeff Vahle (President)[2] |

Number of employees | 77,000+[3] |

| Parent | Disney Parks, Experiences and Products (The Walt Disney Company) |

| Walt Disney World |

|---|

| Theme parks |

| Water parks |

| Other attractions |

| Hotels |

| Transport |

Coordinates: 28°22′20″N 81°32′58″W / 28.37222°N 81.54944°W[4]

The Walt Disney World Resort, also called Walt Disney World or Disney World, is an entertainment resort complex in Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista, Florida, United States, near the cities of Orlando and Kissimmee. Opened on October 1, 1971, the resort is operated by Disney Parks, Experiences and Products, a division of The Walt Disney Company. The property covers nearly 25,000 acres (39 sq mi; 101 km2), of which half has been used.[5] The resort comprises four theme parks (Magic Kingdom, Epcot, Disney's Hollywood Studios, and Disney's Animal Kingdom), two water parks (Disney's Blizzard Beach and Disney's Typhoon Lagoon), 31 themed resort hotels, nine non-Disney hotels, several golf courses, a camping resort, and other entertainment venues, including the outdoor shopping center Disney Springs. On October 1, 2021 Walt Disney started their celebration of its 50th year anniversary which will last for 18 consecutive months ending on March 31, 2023.[6]

Designed to supplement Disneyland in Anaheim, California, which had opened in 1955, the complex was developed by Walt Disney in the 1960s. "The Florida Project", as it was known, was intended to present a distinct vision with its own diverse set of attractions. Walt Disney's original plans also called for the inclusion of an "Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow" (EPCOT), a planned community intended to serve as a testbed for new city-living innovations. Walt Disney died on December 15, 1966, during the initial planning of the complex. After his death, the company wrestled with the idea of whether to bring the Disney World project to fruition; however, Walt's older brother, Roy O. Disney, came out of retirement to make sure Walt's biggest dream was realized. Construction started in 1967, with the company instead building a resort similar to Disneyland, abandoning the experimental concepts for a planned community. The Magic Kingdom was the first theme park to open in the complex, in 1971, followed by Epcot (1982), Disney's Hollywood Studios (1989), and Disney's Animal Kingdom (1998). It was Roy who insisted the name of the entire complex be changed from Disney World to Walt Disney World, ensuring that people would remember that the project was Walt's dream.

In 2018, Walt Disney World was the most visited vacation resort in the world, with an average annual attendance of more than 58 million.[7] The resort is the flagship destination of Disney's worldwide corporate enterprise and has become a popular staple in American culture. In 2020[update], Walt Disney World was chosen to host the NBA Bubble for play of the 2019–20 season of the National Basketball Association to resume at the ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex. Walt Disney World is also covered by an FAA prohibited airspace zone that restricts all airspace activities without approval from the Federal government of the United States, including usage of drones; this level of protection is otherwise only offered to American critical infrastructure (like the Pantex nuclear weapons plant), military bases, the Washington, DC Metropolitan Area Special Flight Rules Area, official presidential travels, and Camp David.[8]

In 2020, Disney World laid off 6,500 employees and only operated at 25% capacity after reopening during the COVID-19 pandemic.[9][10]

On April 22, 2022, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed a bill into law which officially stripped the Walt Disney Company of its longtime self-governing status in the area around Walt Disney World by June 2023.[11][12]

History

Planning and construction

Conception

In 1959, Walt Disney Productions began looking for land to house a second resort to supplement Disneyland in Anaheim, California, which had opened in 1955. Market surveys at the time revealed that only 5% of Disneyland's visitors came from east of the Mississippi River, where 75% of the population of the United States lived. Additionally, Walt Disney disliked the businesses that had sprung up around Disneyland and wanted more control over a larger area of land in the next project.[13]

Walt Disney took a flight over a potential site in Orlando, Florida—one of many—in November 1963. After witnessing the well-developed network of roads and taking the planned construction of both Interstate 4 and Florida's Turnpike into account, with McCoy Air Force Base (later Orlando International Airport) to the east, Disney selected a centrally located site near Bay Lake.[14] The development was referred to in-house as "The Florida Project".[15] To avoid a burst of land speculation, Walt Disney Productions used various dummy corporations to acquire 27,443 acres (43 sq mi; 111 km2) of land.[14] In May 1965, some of these major land transactions were recorded a few miles southwest of Orlando in Osceola County. In addition, two large tracts totaling $1.5 million were sold, and smaller tracts of flatlands and cattle pastures were purchased by exotically named companies, such as the "Ayefour Corporation", "Latin-American Development and Management Corporation", and the "Reedy Creek Ranch Corporation". Some are now memorialized on a window above Main Street, U.S.A. in the Magic Kingdom. The smaller parcels of land acquired were called "outs". They were five-acre (2 ha) lots platted in 1912 by the Munger Land Company and sold to investors. Most of the owners in the 1960s were happy to get rid of the land, which was mostly swamp at the time. Another issue was the mineral rights to the land, which were owned by Tufts University. Without the transfer of these rights, Tufts could come in at any time and demand the removal of buildings to obtain minerals. Eventually, Disney's team negotiated a deal with Tufts to buy the mineral rights for $15,000.[16]

Working strictly in secrecy, real estate agents unaware of their client's identity began making offers to landowners in April 1964, in parts of southwest Orange and northwest Osceola counties. The agents were careful not to reveal the extent of their intentions, and they were able to negotiate numerous land contracts with some landowners, including large tracts of land for as little as $100 an acre.[17] With the understanding that the recording of the first deeds would trigger intense public scrutiny, Disney delayed the filing of paperwork until a large portion of the land was under contract.[18]

Early rumors and speculation about the land purchases assumed possible development by NASA in support of the nearby Kennedy Space Center, as well as references to other famous investors, such as Ford, the Rockefellers, and Howard Hughes.[18] An Orlando Sentinel news article published weeks later, on May 20, 1965, acknowledged a popular rumor that Disney was building an "East Coast" version of Disneyland. However, the publication denied its accuracy based on an earlier interview with Disney at Kennedy Space Center, in which he claimed a $50 million investment was in the works for Disneyland, and that he had no interest in building a new park.[18] In October 1965, editor Emily Bavar from the Sentinel visited Disneyland during the park's 10th-anniversary celebration. In an interview with Disney, she asked him if he was behind recent land purchases in Central Florida. Bavar later described that Disney "looked like I had thrown a bucket of water in his face", before denying the story.[18] His reaction, combined with other research obtained during her Anaheim visit, led Bavar to author a story on October 21, 1965, where she predicted that Disney was building a second theme park in Florida.[18] Three days later, after gathering more information from various sources, the Sentinel published another article headlined, "We Say: 'Mystery Industry' Is Disney".[18]

Walt Disney had originally planned to publicly reveal Disney World on November 15, 1965, but in light of the Sentinel story, Disney asked Florida Governor Haydon Burns to confirm the story on October 25. His announcement called the new theme park "the greatest attraction in the history of Florida".[18] The official reveal was kept on the previously planned November 15 date, and Disney joined Burns in Orlando for the event.[18]

Roy Disney's oversight of construction

Walt Disney died from circulatory collapse caused by smoking related lung cancer on December 15, 1966, before his vision was realized.[19] His brother and business partner, Roy O. Disney, postponed his retirement to oversee construction of the resort's first phase.

On February 2, 1967, Roy O. Disney held a press conference at the Park Theatres in Winter Park, Florida. The role of EPCOT was emphasized in the film that was played. After the film, it was explained that for Disney World, including EPCOT, to succeed, a special district would have to be formed: the Reedy Creek Improvement District with two cities inside it, Bay Lake and Reedy Creek, now Lake Buena Vista. In addition to the standard powers of an incorporated city, which include issuance of tax-free bonds, the district would have immunity from any current or future county or state land-use laws. The only areas where the district had to submit to the county and state would be property taxes and elevator inspections.[13] The legislation forming the district and the two cities, one of which was the Reedy Creek Improvement Act, was signed into law by Florida Governor Claude R. Kirk, Jr. on May 12, 1967.[20] The Supreme Court of Florida then ruled in 1968 that the district was allowed to issue tax-exempt bonds for public projects within the district, despite the sole beneficiary being Walt Disney Productions.

The district soon began construction of drainage canals, and Disney built the first roads and the Magic Kingdom. The Contemporary Resort Hotel and the Polynesian Village Resort were also completed in time for the park's opening on October 1, 1971.[21][22] The Palm and Magnolia golf courses near the Magic Kingdom had opened a few weeks before, while Fort Wilderness opened one month later. Twenty-four days after the park opened, Roy O. Disney dedicated the property and declared that it would be known as "Walt Disney World", in his brother's honor. In his own words: "Everyone has heard of Ford cars. But have they all heard of Henry Ford, who started it all? Walt Disney World is in memory of the man who started it all, so people will know his name as long as Walt Disney World is here." After the dedication, Roy Disney asked Walt's widow, Lillian, what she thought of Walt Disney World. According to biographer Bob Thomas, she responded, "I think Walt would have approved." Roy Disney died at age 78 on December 20, 1971, less than three months after the property opened.[23]

Admission prices in 1971 were $3.50 for adults, $2.50 for juniors under age 18, and one dollar for children under twelve.[21]

1980s–2020

Much of Walt Disney's plans for his Progress City concept were abandoned after his death and after the company board decided that it did not want to be in the business of running a city. The concept evolved into the resort's second theme park, EPCOT Center, which opened in 1982 (renamed EPCOT in 1996). While still emulating Walt Disney's original idea of showcasing new technology, the park is closer to a world's fair than a "community of tomorrow". One of EPCOT's main attractions is the "World Showcase", which highlights 11 countries across the globe. Some of the urban planning concepts from the original idea of EPCOT would instead be integrated into the community of Celebration, Florida, much later. The resort's third theme park, Disney-MGM Studios (renamed Disney's Hollywood Studios in 2008), opened in 1989 and is inspired by show business.

In the early 1990s, the resort was seeking permits for expansion. There was considerable environmentalist push-back, and the resort was convinced to engage in mitigation banking. In an agreement with The Nature Conservancy and the state of Florida, Disney purchased 8,500 acres (3,400 ha) of land, adjacent to the park for the purpose of rehabilitating wetland ecosystems. The Disney Wilderness Preserve was established in April 1993, and the land was subsequently transferred to The Nature Conservancy.[24] The Walt Disney Company provided additional funds for landscape restoration and wildlife monitoring.[25]

The resort's fourth theme park, Disney's Animal Kingdom, opened in 1998.

In October 2009, Disney World announced a competition to find a town to become twinned with. In December 2009, after Rebecca Warren won the competition with a poem, they announced the resort will be twinned with the English town of Swindon.[26]

George Kalogridis was named president of the resort in December 2012, replacing Meg Crofton, who had overseen the site since 2006.

On January 21, 2016, the resort's management structure was changed, with general managers within a theme park being in charge of an area or land, instead of on a functional basis, as previously configured. Theme parks have already had a vice-president overseeing them. Disney Springs and Disney Sports were also affected. Now hotel general managers manage a single hotel instead of some managing multiple hotels.[27]

On October 18, 2017, it was announced that resort visitors could bring pet dogs to Disney's Yacht Club Resort, Disney's Port Orleans Resort – Riverside, Disney's Art of Animation Resort, and Disney's Fort Wilderness Resort & Campground.[28]

In 2019, Josh D'Amaro replaced George Kalogridis as president of the resort. He had previously held the position of vice president of Animal Kingdom.[29] D'Amaro was subsequently promoted to chairman of Disney Parks, Experiences and Products in May 2020, succeeding Bob Chapek, who was promoted to CEO of The Walt Disney Company in February 2020. Jeff Vahle, who served as president of Disney Signature Experiences subsequently took over as president of the resort.[30]

March 2020–present

On March 12, 2020, a Disney spokesperson announced that Disney World and Disneyland Paris would close business, beginning March 15, 2020.[31]

In June 2020[update], Walt Disney World was chosen to host the NBA Bubble for play of the 2019–20 season of the National Basketball Association to resume at the ESPN Wide World of Sports Complex.[32] It was also the site for the MLS is Back Tournament, also held at the Sports Complex.

On July 11, 2020, Disney World officially reopened, beginning operations at 25% capacity at the Magic Kingdom and Disney's Animal Kingdom, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in Florida.[33] Four days later, Epcot and Disney's Hollywood Studios for operation at 25% capacity to the public.[34] Masks were required at all times (including outdoors, on attractions, and while taking photos), all guests were required to have their temperature taken upon entry, plexiglass was installed on various attractions and transportation offerings, and shows that drew large crowds, such as parades and nighttime shows including Fantasmic! and Happily Ever After were not offered.[35]

In November 2020, the resort increased the guest capacity to 35% at all four theme parks, and on May 13, 2021, CEO Bob Chapek announced a further increase of capacity, effective immediately; however, he did not say to what capacity level it would be raised.[36] By mid-June 2021, temperature checks and mask mandates (except while on Disney transportation) had been lifted.[37] In late July 2021, mask mandates were reinstated for all attractions and indoor areas in light of new guidance issued by the Centers for Disease Control as the delta variant drove a significant increase in local cases. These reinstated mandates were lifted in February 2022.[38] In April 2022, following a court decision ending the federal mask mandate for public transportation, the mask mandates on Disney transportation were lifted.[39]

Starting on October 1, 2021, the resort is honoring its 50th anniversary with "The World's Most Magical Celebration".[40]

Disney's Magical Express, a complimentary transportation and luggage service offered to Walt Disney Resort guests that began in 2005, ended in January 2022.[41] In August 2021, the Walt Disney Company announced that FastPass+, which had been free since its introduction in 1999, would be retired and replaced with Genie+, a system costing guests $15 per day with the option of adding "Lightning Lane," which will be used for top-tier attractions, for an additional charge.[42]

On April 22, 2022, the self-governing status which the Walt Disney Company had in the area around Disney World for more than 50 years came to an end after Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law legislation requiring the area to come under the legal jurisdiction of the state of Florida.[43] The new law would also officially abolish The Reedy Creek Improvement District which the Walt Disney Company has used to run the area since May 1967, when former Florida Governor Claude Kirk signed into law legislation which granted the company special status.[43] The law goes into effect in June of 2023.[12][44]

Timeline

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1965 | Walt Disney announces the Florida Project |

| 1966 | Walt Disney dies of lung cancer at age 65 |

| 1967 | Construction of Walt Disney World Resort begins |

| 1971 |

|

| 1972 |

|

| 1973 |

|

| 1974 | Discovery Island opens |

| 1975 |

|

| 1976 | Disney's River Country opens |

| 1980 |

|

| 1982 | EPCOT Center opens |

| 1983 | Horizons opens at Epcot on October 1. |

| 1986 | The Golf Resort is expanded and renamed The Disney Inn |

| 1988 |

|

| 1989 |

|

| 1990 |

|

| 1991 |

|

| 1992 |

|

| 1993 | Mission to Mars closes at Magic Kingdom on October 4. |

| 1994 |

|

| 1995 |

|

| 1996 |

|

| 1997 | |

| 1998 |

|

| 1999 |

|

| 2000 | The Villas at Disney's Wilderness Lodge opens |

| 2001 |

|

| 2002 |

|

| 2003 |

|

| 2004 |

|

| 2006 | Expedition Everest: Legend of the Forbidden Mountain opens at Animal Kingdom on April 7. |

| 2007 |

|

| 2008 | Disney-MGM Studios is renamed Disney's Hollywood Studios |

| 2009 | |

| 2011 |

|

| 2012 |

|

| 2013 | The Villas at Disney's Grand Floridian Resort & Spa opens |

| 2014 |

|

| 2015 |

|

| 2016 |

|

| 2017 |

|

| 2018 |

|

| 2019 |

|

| 2020 |

|

| 2021 |

|

| 2022 |

|

| 2023 |

|

Future expansion

The resort has a number of expansion projects planned or ongoing, including:

- TRON Lightcycle Run at Magic Kingdom

- Enhancements at Epcot continue, including a walkthrough attraction Journey of Water, inspired by Moana (2016 film), and a newly designed central spine which will include a statue of Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse. The Play! Pavilion was also announced to be coming to Epcot, using to building formerly occupied by Wonders of Life.

- Flamingo Crossings, a shopping complex similar to Disney Springs, currently opening in phases.

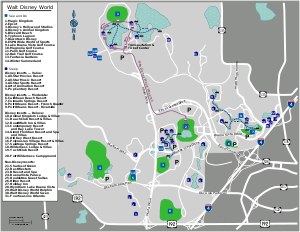

Location

The Florida resort is not within Orlando city limits but is southwest of Downtown Orlando. Much of the resort is in southwestern Orange County, with the remainder in adjacent Osceola County. The property includes the cities of Lake Buena Vista and Bay Lake which are governed by the Reedy Creek Improvement District. The site is accessible from Central Florida's Interstate 4 via Exits 62B (World Drive), 64B (US 192 West), 65B (Osceola Parkway West), 67B (SR 536 West), and 68 (SR 535 North), Exit 6 on SR 417 South, the Central Florida GreeneWay and Exit 8 on SR 429, the Western Beltway. At its founding, the resort occupied approximately 27,443 acres (43 sq mi; 111 km2).[14] Portions of the property have since been sold or de-annexed, including land now occupied by the Disney-built community of Celebration. By 2014, the resort occupied nearly 25,000 acres (39 sq mi; 101 km2).[5] The company acquired nearly 3,000 additional acres, in separate transactions, between December 2018 and April 2020.[47][48][49]

Attractions

Cinderella Castle at Magic Kingdom

Spaceship Earth at Epcot

The Chinese Theatre at Disney's Hollywood Studios

Theme parks

- Magic Kingdom, opened October 1, 1971

- Epcot, opened October 1, 1982

- Disney's Hollywood Studios, opened May 1, 1989

- Disney's Animal Kingdom, opened April 22, 1998

Water parks

- Disney's Typhoon Lagoon, opened June 1, 1989

- Disney's Blizzard Beach, opened April 1, 1995

Other attractions

- Multiple resorts across Disney property offer a variety of spa treatments including Disney's Grand Floridian and Disney's Coronado Springs Resort

- Disney's Boardwalk, located outside of their Boardwalk Inn, functions as an entertainment, dining, and shopping district.[50]

- Epcot has annual festivals that run for limited amounts of time throughout the year like the Epcot Flower and Garden Festival, Epcot Festival of the Arts, and the Epcot Food and Wine Festival

- Disney does special ticketed events throughout the year including the Mickey's Not So Scary Halloween Party, which usually runs late August through October, and Mickey's Very Merry Christmas Party

- Disney Springs, opened March 22, 1975 (Previously known as Lake Buena Vista Shopping Village, Disney Village Marketplace, and Downtown Disney)[51]

- Disney's Wedding Pavilion, opened July 15, 1995

- ESPN Wide World of Sports, opened March 28, 1997

Golf and recreation

Disney's property includes four golf courses. The three 18-hole golf courses are Disney's Palm (4.5 stars), Disney's Magnolia (4 stars), and Disney's Lake Buena Vista (4 stars). There is also a nine-hole walking course (no electric carts allowed) called Oak Trail, designed for young golfers. The Magnolia and Palm courses played home to the PGA Tour's Children's Miracle Network Hospitals Classic. Arnold Palmer Golf Management manages the Disney golf courses.[52]

Additionally, there are two themed miniature golf complexes, each with two courses, Fantasia Gardens and Winter Summerland.[53] The two courses at Fantasia Gardens are Fantasia Garden and Fantasia Fairways. The Garden course is a traditional miniature-style course based on the "Fantasia" movies with musical holes, water fountains and characters. Fantasia Fairways is a traditional golf course on miniature scale having water hazards and sand traps.[54]

The two courses at Winter Summerland are Summer and Winter, both themed around Santa. Summer is the more challenging of the two 18-hole courses.[54]

| Tee | Rating/Slope | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Out | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | In | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | 76.0 / 141 | 428 | 417 | 170 | 542 | 492 | 231 | 422 | 614 | 500 | 3816 | 526 | 399 | 169 | 384 | 592 | 203 | 450 | 485 | 492 | 3700 | 7516 |

| Blue | 74.0 / 137 | 424 | 351 | 161 | 535 | 446 | 202 | 410 | 605 | 426 | 3560 | 522 | 382 | 163 | 374 | 588 | 200 | 398 | 430 | 456 | 3513 | 7073 |

| White | 71.6 / 130 | 409 | 335 | 140 | 499 | 418 | 168 | 380 | 534 | 393 | 3276 | 513 | 355 | 156 | 320 | 532 | 179 | 373 | 399 | 455 | 3282 | 6558 |

| Gold | 69.0 / 121 | 384 | 317 | 125 | 479 | 355 | 115 | 339 | 519 | 327 | 2960 | 496 | 309 | 148 | 308 | 516 | 143 | 349 | 381 | 417 | 3067 | 6027 |

| Red | 69.6 / 126 | 285 | 225 | 110 | 370 | 347 | 107 | 306 | 402 | 316 | 2468 | 430 | 300 | 140 | 296 | 417 | 128 | 292 | 301 | 355 | 2659 | 5127 |

| Par | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 36 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 36 | 72 | |

| SI | Men's | 3 | 15 | 17 | 11 | 1 | 13 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 2 | 6 | |||

| SI | Ladies' | 7 | 13 | 17 | 11 | 3 | 15 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 18 | 2 | 10 | 12 | 16 | 14 | 8 | 4 | 6 |

Former attractions

- Discovery Island – an island in Bay Lake that was home to many species of animals and birds. It opened on April 8, 1974, and closed on April 8, 1999.

- Disney's River Country – the first water park at the Walt Disney World Resort. It opened on June 20, 1976, and closed on November 2, 2001.[56]

- Walt Disney World Speedway – a racetrack at Walt Disney World and included the Richard Petty Driving Experience. It opened November 28, 1995, and closed on August 9, 2015.

- DisneyQuest – an indoor interactive theme park that featured many arcade games and virtual attractions. It opened June 19, 1998 as part of an unsuccessful attempt to launch a chain of similar theme parks. It closed on July 2, 2017, to be replaced by the NBA Experience.[57]

- La Nouba by Cirque du Soleil – opened December 23, 1998, and closed after December 31, 2017.[58]

Resorts

Of the thirty-four resorts and hotels on the Walt Disney World property, 28 are owned and operated by Walt Disney Parks, Experiences and Consumer Products. These are classified into four categories—Deluxe, Moderate, Value, and Disney Vacation Club Villas—and are located in one of five resort areas: the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, Wide World of Sports, Animal Kingdom, or Disney Springs resort areas. There is also the Other Select Deluxe Resorts category used to describe two resorts in the Epcot Resorts Area that carry Walt Disney World branding but are managed by a third party.

While all of the Deluxe resort hotels have achieved an AAA Four Diamond rating, Disney's Grand Floridian Resort & Spa is considered the highest-tier flagship luxury resort on the Walt Disney World Resort complex.[59]

On-site Disney resorts

| Name | Image | Opening date | Theme | Number of rooms | Resort area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deluxe resorts | |||||

| Disney's Animal Kingdom Lodge |  |

April 16, 2001 | African Wildlife preserve | 1,307 | Animal Kingdom |

| Disney's Beach Club Resort |  |

November 19, 1990 | Newport Beach cottage | 576 | Epcot |

| Disney's BoardWalk Inn |  |

July 1, 1996 | Early-20th-century Atlantic and Ocean City | 378 | |

| Disney's Yacht Club Resort |  |

November 5, 1990 | Martha's Vineyard Resort | 621 | |

| Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser | March 1, 2022[60] | Star Wars starship | 100 | ||

| Disney's Contemporary Resort |  |

October 1, 1971 | Modern | 655 | Magic Kingdom |

| Disney's Grand Floridian Resort & Spa |  |

June 28, 1988 | Early-20th-century Florida | 867 | |

| Disney's Polynesian Village Resort |  |

October 1, 1971 | South Pacific | 492 | |

| Disney's Wilderness Lodge |  |

May 28, 1994 | Pacific Northwest, National Park Service rustic | 729 | |

| Moderate resorts | |||||

| Disney's Caribbean Beach Resort |  |

October 1, 1988 | Caribbean Islands | 1,536 | Epcot |

| Disney's Coronado Springs Resort |  |

August 1, 1997 | Mexico, American Southwest | 1,915 | Animal Kingdom |

| Disney's Port Orleans Resort – French Quarter |  |

May 17, 1991 | New Orleans French Quarter | 1,008 | Disney Springs |

| Disney's Port Orleans Resort – Riverside |  |

February 2, 1992 | Deep South | 2,048 | |

| Value resorts | |||||

| Disney's All-Star Movies Resort |  |

January 15, 1999 | Disney films | 1,920 | Animal Kingdom |

| Disney's All-Star Music Resort | November 22, 1994 | Music | 1,604 | ||

| Disney's All-Star Sports Resort |  |

April 24, 1994 | Sports | 1,920 | |

| Disney's Art of Animation Resort |  |

May 31, 2012 | Disney and Pixar animated films | 1,984 | Disney's Hollywood Studios |

| Disney's Pop Century Resort |  |

December 14, 2003 | 20th Century American pop culture | 2,880 | |

| Disney Vacation Club | |||||

| Bay Lake Tower |  |

August 4, 2009 | Modern | 428 | Magic Kingdom |

| Disney's Animal Kingdom Villas | August 15, 2007 | African safari lodge | 708 | Animal Kingdom | |

| Disney's Beach Club Villas | July 1, 2002 | Newport resort | 282 | Epcot | |

| Disney's Boardwalk Villas | July 1, 1996 | Early-20th-century Atlantic City | 530 | ||

| Disney's Old Key West Resort | December 20, 1991 | Early-20th-century Key West | 761 | Disney Springs | |

| Disney's Polynesian Villas & Bungalows | April 1, 2015 | South Seas | 380 | Magic Kingdom | |

| Disney's Saratoga Springs Resort & Spa |  |

May 17, 2004 | 1880s Upstate New York resort | 1,320 | Disney Springs |

| The Villas at Disney's Grand Floridian Resort & Spa | October 23, 2013 | Early-20th-century Florida | 147 | Magic Kingdom | |

| Boulder Ridge Villas | November 15, 2000 | Pacific Northwest | 181 | ||

| Copper Creek Villas & Cabins | July 17, 2017 | Pacific Northwest | 184 | ||

| Disney's Riviera Resort | December 16, 2019 | European Riviera | 300 | Epcot | |

| Reflections – A Disney Lakeside Lodge | TBD | Nature | 900 | Magic Kingdom[61] | |

| Cabins and campgrounds | |||||

| Disney's Fort Wilderness Resort & Campground |  |

November 19, 1971 | Rustic Woods Camping | 800 campsites 409 cabins |

Magic Kingdom |

| Residential areas | |||||

| Golden Oak at Walt Disney World Resort | Fall 2011 | Varies | 450 homes | Magic Kingdom | |

On-site non-Disney resorts

| Hotel name | Image | Opening date | Theme | Number of rooms | Owner | Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best Western Lake Buena Vista Resort Hotel | November 21, 1972 | None | 325 | Drury Hotels | Hotel Plaza Boulevard, close to Disney Springs | |

| DoubleTree Suites by Hilton Orlando – Disney Springs Area | March 15, 1987 | 229 | Hilton Hotels Corporation | |||

| Wyndham Lake Buena Vista | October 15, 1972 | 626 | Wyndham Hotels & Resorts | |||

| Hilton Orlando Lake Buena Vista |  |

November 23, 1983 | 787 | Hilton Hotels Corporation | ||

| Holiday Inn Orlando - Disney Springs Area | February 8, 1973 | 323 | InterContinental Hotels Group | |||

| B Resort & Spa | October 1, 1972 | 394 | B Hotels & Resorts | |||

| Hilton Orlando Buena Vista Palace |  |

March 10, 1983 | 1,014 | Hilton Hotels Corporation | ||

| Four Seasons Resort Orlando at Walt Disney World Resort | August 3, 2014 | 450 | Four Seasons | Magic Kingdom | ||

| Bonnet Creek Resort | Various | Various, 3,000 total | Hilton Worldwide, Wyndham Worldwide | Epcot | ||

| Shades of Green |  |

December 1973 | Upscale Country Club | 586 | United States Department of Defense | Magic Kingdom |

| Walt Disney World Dolphin |  |

June 1, 1990 | Seaside Floridian Resort & Under the Sea | 1509 | Marriott International | Epcot |

| Walt Disney World Swan |  |

January 13, 1990 | Seaside Floridian Resort & Under the Sea | 758 | Marriott International | Epcot |

| Walt Disney World Swan Reserve | November 4, 2021 | Upscale Boutique Hotel | 349 | Marriott International | Epcot |

Former resorts

- The Golf Resort – Became The Disney Inn, and later became Shades of Green.

- Disney's Village Resort – Became the Villas at Disney Institute and then Disney's Saratoga Springs Resort & Spa. The "Tree House" Villas were decommissioned for a time because they were not accessible to disabled guests. Until early 2008, they were used for International Program Cast Member housing. In February 2008, Disney submitted plans to the South Florida Water Management District to replace the 60 existing villas with 60 new villas.[62] The Treehouse Villas opened during the summer of 2009.

- Celebration – a town designed and built by Disney, now managed by a resident-run association.

- Lake Buena Vista – Disney originally intended this area to become a complete community with multiple residences, shopping, and offices, but transformed the original homes into hotel lodging in the 1970s, which were demolished in the early 2000s to build Disney's Saratoga Springs Resort & Spa

Never-built resorts

- Disney's Asian Resort

- Disney's Persian Resort

- Disney's Venetian Resort

- Disney's Mediterranean Resort

- Fort Wilderness Junction

Disney's Magical Express

Guests with a Disney Resort reservation (excluding the Walt Disney World Swan and Dolphin) that arrive at Orlando International Airport can be transported to their resort from the airport using the complimentary Disney's Magical Express service, which is operated by Mears Destination Services. Guests can also have their bags picked up and transported to their resort for them through a contract with BAGS Incorporated on participating airlines. Many resorts feature Airline Check-in counters for guests returning to the airport. Here their bags will be checked all the way through to their final destination and they can also have boarding passes printed for them. Current participating airlines are Delta, United, American, JetBlue, Southwest and Alaska Airlines. It was announced in early January 2021, that Disney would be ending the service on January 1, 2022, citing a shift in consumer demand for more flexibility in transportation options.[63]

Attendance

In the first year of opening, the park attracted 10,712,991 visitors.[64] In 2018, the resort's four theme parks all ranked in the top 9 on the list of the 25 most visited theme parks in the world: (1st) Magic Kingdom—20,859,000 visitors; (6th) Disney's Animal Kingdom—13,750,000 visitors; (7th) Epcot—12,444,000 visitors; and (9th) Disney's Hollywood Studios—11,258,000 visitors.[7] By October 2020, maximum Disney World attendance was still allowed to only remain at 25% capacity due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[10] A recent study found that reducing Magic Kingdom park capacity to 25% would result in a 54.1% reduction in annual attendance. This capacity limit causes less annual revenue, and may lower the number of visitors to the Orlando region.[65]

| Year | Magic Kingdom | Epcot | Disney's Hollywood Studios | Disney's Animal Kingdom | Overall | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 17,063,000 | 10,935,000 | 9,608,000 | 9,540,000 | 47,146,000 | [66] |

| 2009 | 17,233,000 | 10,990,000 | 9,700,000 | 9,590,000 | 47,513,000 | [67] |

| 2010 | 16,972,000 | 10,825,000 | 9,603,000 | 9,686,000 | 47,086,000 | [68] |

| 2011 | 17,142,000 | 10,826,000 | 9,699,000 | 9,783,000 | 47,450,000 | [69] |

| 2012 | 17,536,000 | 11,063,000 | 9,912,000 | 9,998,000 | 48,509,000 | [70] |

| 2013 | 18,588,000 | 11,229,000 | 10,110,000 | 10,198,000 | 50,125,000 | [71] |

| 2014 | 19,332,000 | 11,454,000 | 10,312,000 | 10,402,000 | 51,500,000 | [72] |

| 2015 | 20,492,000 | 11,798,000 | 10,828,000 | 10,922,000 | 54,040,000 | [73] |

| 2016 | 20,395,000 | 11,712,000 | 10,776,000 | 10,844,000 | 53,727,000 | [74] |

| 2017 | 20,450,000 | 12,200,000 | 10,722,000 | 12,500,000 | 55,872,000 | [75] |

| 2018 | 20,859,000 | 12,444,000 | 11,258,000 | 13,750,000 | 58,311,000 | [7] |

| 2019 | 20,963,000 | 12,444,000 | 11,483,000 | 13,888,000 | 58,778,000 | [76] |

| 2020 | 6,941,000 | 4,044,000 | 3,675,000 | 4,166,000 | 18,826,000 | [77] |

Operations

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2015) |

Transportation

The Walt Disney World Resort is serviced by Disney Transport, a complimentary mass transportation system allowing guest access across the property. The fare-free system utilizes buses, monorails, gondola lifts, watercraft, and parking lot trams.

The Walt Disney World Monorail System provides free transportation at Walt Disney World; guests can board the monorail and travel between the Magic Kingdom and Epcot, including select on-property resorts such as The Grand Floridian and The Polynesian Village. The system operates on three routes that interconnect at the Transportation and Ticket Center (TTC), adjacent to the Magic Kingdom's parking lot. Disney Transport owns a fleet of Disney-operated buses on the property, that is also complimentary for guests.

A gondola lift system, dubbed Disney Skyliner, opened in 2019. The system's three lines connect Disney's Hollywood Studios and Epcot with four resort hotels.[78]

Disney Transport also operates a fleet of watercraft, ranging in size from water taxis, up to the ferries that connect the Magic Kingdom to the Transportation and Ticket Center. Disney Transport is also responsible for maintaining the fleet of parking lot trams that are used for shuttling visitors between the various theme park parking lots and their respective main entrances.

In addition to its free transportation methods, in conjunction with Lyft, Walt Disney World also offers a vehicle for hire service for a fee. The Minnie Van Service are Chevy Traverses dressed in a Minnie Mouse red-and-white polka dot design that can accommodate up to six people and have two carseats available to anyone that is within the Walt Disney World Resort limits. Cast members can install the car seats.[79][80] Some of the unique advantages that the Minnie Van Service offers over a normal ride share is the ability to be dropped off in the Magic Kingdom bus loop (instead of at the TTC like the other ride shares) and being able to ride to any point in Fort Wilderness.

Parking

Upon arriving at the park, there are several lots that can be used to park vehicles. At the theme parks, which include Animal Kingdom, Magic Kingdom, Epcot and Hollywood Studios, there is a single lot used. Guests are able to access each of these four parks when their vehicle is left in one of these lot. Guests have the choice to buy a pass for either standard parking or preferred parking. Preferred parking can be purchased for a higher cost, however, it allows guests to park their vehicle closer to the park entrance. Trams are available to guests at no cost. They provide transportation from the parking lot to the main entrance. Parking areas are also available to those with disabilities. These designated parking lots allow for guests with disabilities to park a shorter distance from the park entrances to minimize any traveling that is necessary. Additionally, guests are given the option of valet parking at an extra cost.

Employment

When the Magic Kingdom opened in 1971, the site employed about 5,500 "cast members".[81] In 2020, Walt Disney World employs more than 77,000 cast members.[3] The largest single-site employer in the United States,[82][83] Walt Disney World has more than 3,000 job classifications with a total 2019 payroll of over $3 billion.[3] The resort also sponsors and operates the Walt Disney World College Program, an internship program that offers American college students (CPs) the opportunity to live in Flamingo Crossings Village, a Disney-owned apartment complex, and work at the resort, and thereby provides much of the theme park and resort "front line" cast members. There is also the Walt Disney World International College Program, an internship program that offers international college students (ICPs) from all over the world the same opportunity. In September 2020, the Walt Disney Company began laying off 6,500 Walt Disney World employees.[9]

Energy use

Walt Disney World requires an estimated 1 billion kilowatt-hours (3.6 billion megajoules) of electricity annually, costing the company nearly $100 million in annual energy consumption.[84] In addition to relying primarily on fossil fuels and nuclear energy from the state's power grid, Walt Disney World has two solar energy facilities on property; a 22-acre (0.034 sq mi; 0.089 km2) Mickey Mouse-shaped solar panel farm near Epcot, and a 270-acre (0.42 sq mi; 1.1 km2) facility near Disney's Animal Kingdom.[85] The larger facility produces enough solar energy to provide electricity to two of the resort's theme parks. The sites are operated by Duke Energy and the Reedy Creek Improvement District, respectively.[85]

The entire Disney Transport bus fleet uses R50 renewable diesel fuel, obtained from used cooking oil and non-consumable food waste from the resort.[85]

Corporate culture

Walt Disney World's corporate culture uses jargon based on theatrical terminology.[86][87] For example, park visitors are always "guests", employees are called "cast members", rides are "attractions" or "experiences", cast members costumed as famous Disney characters in a way that does not cover their faces are known as "face characters", jobs are "roles", and public and nonpublic areas are respectively labeled "onstage" and "backstage".[86][87]

Self-Government and Security

Disney's security personnel are generally dressed in typical security guard uniforms, though some of the personnel are dressed as tourists in plain clothes. Since September 11, 2001, uniformed security has been stationed outside each Disney park in Florida to search guests' bags as they enter the parks. Starting April 3, 2017, bag checkpoints have been placed at Magic Kingdom's resort monorail entryways and the Transportation and Ticket Center's ferry entry points prior to embarkation as well as the walkway from Disney's Contemporary Resort. Guests arriving at the Transportation and Ticket Center by tram or tour bus will be screened at the former tram boarding areas. Guests arriving by Disney Resort hotel bus or Minnie Van have their own bag check just outside the bus stops. Guests arriving via Magic Kingdom Resort boat launch are bag checked on the arrival dock outside Magic Kingdom.[88]

The land where Walt Disney World resides is part of the Reedy Creek Improvement District (RCID), a governing jurisdiction created on May 1967 by the State of Florida at the request of Disney.[89][43] RCID provides 911 services, fire, environmental protection, building code enforcement, utilities and road maintenance, but does not provide law enforcement services. The approximately 800 security staff are instead considered employees of the Walt Disney Company. Arrests and citations are issued by the Florida Highway Patrol along with the Orange County and Osceola County sheriffs deputies who patrol the roads. Disney security does maintain a fleet of security vans equipped with flares, traffic cones, and chalk commonly used by police officers. These security personnel are charged with traffic control by the RCID and may only issue personnel violation notices to Disney and RCID employees, not the general public.[90][91]

Despite the appearance of the uniformed security personnel, they are not considered a legal law enforcement agency. Disney and the Reedy Creek Improvement District were sued for access to Disney Security records by Bob and Kathy Sipkema following the death of their son at the resort in 1994. The court characterized Disney security as a "night watchman" service, not a law enforcement agency, meaning it is not subject to Florida's open records laws. An appeals court later upheld the lower court's ruling.[92]

In late 2015, Disney confirmed the addition of randomized secondary screenings and dogs trained to detect body-worn explosives within parks, in addition to metal detectors at entrances. It has also increased the number of uniformed security personnel at Walt Disney World and Disneyland properties.[93]

Disney Security personnel in Florida have investigated traffic accidents and issued accident reports. The forms used by Disney Security may be confused with official, government forms by some.[citation needed]

The Orange County Sheriff maintains an office on Disney property, but this is primarily to process guests accused of shoplifting by Disney security personnel.[94]

Although the scattering of ashes on Disney property is illegal, The Wall Street Journal reported in October 2018 that Walt Disney World parks were becoming a popular spot for families to scatter the ashes of loved ones, with the Haunted Mansion at Magic Kingdom being the favorite location. The practice is unlawful and prohibited on Disney property, and anyone spreading cremated remains is escorted from the park.[95]

On April 22, 2022, the Walt Disney Company's self-governing authority of all the area surrounding Walt Disney World came to an end after Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law legislation requiring Walt Disney World's Reedy Creek Improvement District to come under the legal jurisdiction of the state of Florida in June 2023.[43][12]

Closures

Walt Disney World has had nine unscheduled closures:[96]

- September 15, 1999, due to Hurricane Floyd

- September 11, 2001, after the September 11, 2001 attacks

- August 13, 2004, due to Hurricane Charley

- September 4–5, 2004, due to Hurricane Frances

- September 26, 2004, due to Hurricane Jeanne

- October 25, 2005, in the morning, due to Hurricane Wilma.

- October 7, 2016, due to Hurricane Matthew

- September 10–11, 2017, due to Hurricane Irma

- September 3, 2019, for about half the day (with the exception of Epcot and Disney Springs), due to Hurricane Dorian

- March 15[97][98] – July 11, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[99] (excluding Disney Springs, which reopened on May 19, 2020[100])

Like its sister resort, parks at the resort may close early to accommodate various special events, such as special press events, tour groups, VIP groups, and private parties. It is common for a corporation to rent entire parks for the evening. In such cases, special passes are issued which are valid for admission to all rides and attractions. At the ticket booths and on published schedules, the guests are notified of the early closures. Then, cast members announce that the parks are closing, sometime before the private event starts, and clear the parks of guests who do not have the special passes.

In October 2020, it was revealed that full capacity attendance was still not permitted, following the COVID-19 closure which occurred earlier in the year.[10] In July 2021, Disney World announced that all its staff workers in the US would have to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 to return to work. It also announced that those who are unvaccinated would have a period of time to get their shots and aimed to return to full capacity for people who are immunized.[101]

Climate

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Management

- Jeff Vahle – president

- Maribeth Bisienere – senior vice president, resorts, transportation, and premium services

- Alison Armor – vice president, transportation operations

- Mahmud Dhanani – vice president, resorts

- Rosalyn Durant – senior vice president, Disney Springs, ESPN Wide World of Sports and water parks

- Faron Kelley – vice president, sports and water parks

- Matt Simon – vice president, Disney Springs

- Jason Kirk – senior vice president, operations

- Jim MacPhee – senior vice president, operations

- Sarah Riles – vice president, Disney's Animal Kingdom

- Jackie Swisher – vice president, Disney's Hollywood Studios

- Melissa Valiquette – vice president, Magic Kingdom

- Maribeth Bisienere – senior vice president, resorts, transportation, and premium services

Walt Disney World's Operations division is undergoing changes to management. This is the reason for there being two senior vice presidents of operations listed, as well as the vice-presidents below them possibly being outdated.[citation needed]

See also

- Disney College Program

- Large amusement railways

- List of Disney attractions that were never built

- List of Disney theme park attractions

- List of incidents at Walt Disney World

- Rail transport in Walt Disney Parks and Resorts

- Walt Disney Travel Company

- Walt Disney World Casting Center

- The Walt Disney World Explorer

- Walt Disney World Hospitality and Recreation Corporation

- Walt Disney World International Program

References

- ^ Schoolfield, Jeremy (October 26, 2021). "Look for Some Fresh Pixie Dust at the Entrances to Walt Disney World Resort". disney.com. The Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "New Leadership Team Announced At Disney Parks, Experiences And Products" (Press release). The Walt Disney Company. May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Fact Sheet" (PDF). Disney Parks, Experiences and Products. February 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Walt Disney World Resort in Geonames.org (cc-by)

- ^ a b "Walt Disney World Fun Facts" (PDF). Walt Disney World News. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Disney World sets end date for 50th anniversary celebration". www.mynews13.com. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c Au, Tsz Yin (Gigi); Chang, Bet; Chen, Bryan; Cheu, Linda; Fischer, Lucia; Hoffman, Marina; Kondaurova, Olga; LaClair, Kathleen; Li, Shaojin; Linford, Sarah; Marling, George; Miller, Erik; Nevin, Jennie; Papamichael, Margreet; Robinett, John; Rubin, Judith; Sands, Brian; Selby, William; Timmins, Matt; Ventura, Feliz; Yoshii, Chris (May 28, 2019). "TEA/AECOM 2018 Theme Index & Museum Index: Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "4/3634 NOTAM Details". tfr.faa.gov. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "6,700 non-union Disney employees in Central Florida among those being laid off". WESH. September 30, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c Deerwester, Jayme (October 13, 2020). "Disney World attendance to stay capped; Disneyland reopening 'not much of a negotiation,' CEO says". USA Today. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ "DeSantis signs bill ending Disney's self-governing status in Florida". NBC News. April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c Anthony Izaguirre (April 22, 2022). "Disney government dissolution bill signed by DeSantis". 620WTMJ. Associated Press. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Fogleson, Richard E. (2003). Married to the Mouse. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-300-09828-0.

- ^ a b c Mannheim, Steve (2002). Walt Disney and the Quest for Community. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited. pp. 6, 68–70. ISBN 978-0-7546-1974-1.

- ^ Patches, Matt (May 20, 2015). "Inside Walt Disney's Ambitious, Failed Plan to Build the City of Tomorrow". Esquire. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Koenig, David (2007). Realityland: True-Life Adventures at Walt Disney World. Irvine, CA: Bonaventure Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-9640605-2-4.

- ^ Mark Andrews (May 30, 1993). "Disney Assembled Cast Of Buyers To Amass Land Stage For Kingdom". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mark Andrews (August 6, 2000). "Disney Pulled Strings So Mouse Moved In With Barely A Squeak". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ Santora, Phil. "The day Walt Disney, an American icon who gave us Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, died". New York Daily News. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (1994). Walt Disney - An American Original. p. 357. Archived from the original on October 24, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "Disney World Florida opens next Friday". Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. UPI. September 27, 1971. p. 11.

- ^ "Walt Disney World opens Florida gates". Lodi News-Sentinel. California. UPI. October 2, 1971. p. 10.

- ^ "Backstage brain Roy Disney dies". St. Petersburg Independent. Florida. Associated Press. December 21, 1971. p. 10–A.

- ^ "Disney Wilderness Preserve". The Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original on August 19, 2003.

- ^ Palmer, Tom (February 16, 2013). "Disney Wilderness Preserve Site Is Internationally Recognized Model for Success". The Ledger. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Peter Woodman (December 7, 2009). "Swindon twinned with Disney World". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 11, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Pedicini, Sandra (January 22, 2016). "Walt Disney World announces management reorganization". Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Trejos, Nancy. "Dogs now welcome at Disney World resorts". USA Today.

- ^ "The Walt Disney Company News". WDWMagic.

- ^ Bevil, Dewayne. "Disney World: Josh D'Amaro promoted; Jeff Vahle takes over as president". orlandosentinel.com.

- ^ "Walt Disney World closes, paralyzing the company's tourism empire". CNN Business.

- ^ Sergent, Jim; Medina, Mark. "How the NBA bubble has taken shape in Disney World". USA TODAY.

- ^ "Magic Kingdom, Animal Kingdom reopen for first time since March". WFLA-TV. July 9, 2020.

- ^ Tremaine, Julie (July 15, 2020). "Disney World Reopens Epcot and Hollywood Studios". CNN.

- ^ Richwine, Lisa (July 12, 2020). "Mandatory masks, Mickey at a distance as Walt Disney World reopens". REUTERS.

- ^ Biesiada, Jamie (May 14, 2021). "Capacity levels are going up at Walt Disney World". Travel Weekly.

- ^ Tyko, Kelly. "Disney World no longer requires masks outdoors, but you'll still need to wear a mask to enter parks and inside". USA TODAY.

- ^ Durkee, Alison. "Disney World And Disneyland Reimpose Mask Mandates Amid Covid-19 Delta Variant Spread". Forbes.

- ^ "Walt Disney World makes masks optional for all areas of resort". NBC News.

- ^ Brown, Forrest (February 25, 2021). "Find out what Disney World has in store for its 50th anniversary celebration in October". CNN Travel. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ Bevil, Dewayne. "Disney ending Magical Express bus service and Extra Magic Hours for hotel guests". orlandosentinel.com.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (August 18, 2021). "To Skip the Line at Disney, Get Ready to Pay a Genie". Archived from the original on December 28, 2021 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ a b c d Morris, Kyle (April 22, 2022). "DeSantis signs bill ending Disney's self-governing status in Florida". Fox News. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ "DeSantis signs bill eliminating Walt Disney World's Reedy Creek district; Fitch warns of bond downgrade". Orlando Sentinel. April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Walt Disney World closes for just fourth time ever as Hurricane Matthew nears". CNBC. October 6, 2016. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ^ "Hurricane Irma causes Disney World to close for sixth time in nearly 50 years". Fox News. September 10, 2017. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Disney World buys 235 acres. Here's what we know". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Storey, Ken. "Disney has been on a land-buying spree. Here's why it probably isn't a new theme park". Orlando Weekly. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ "Disney Bought Nearly 3K Acres of Land Since 2018 - But Not for a New Park". Inside the Magic. December 31, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ "Disney's BoardWalk". Walt Disney World. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Levine, Arthur (June 1, 2016). "Disney Springs: The story behind Disney World's former Downtown Disney". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ Jason Garcia (August 24, 2011). "Disney golf: Disney World to turn its golf courses over to Arnold Palmer". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 1, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Barnes, Susan B. (July 27, 2015). "Putt putt your way across the USA". Detroit Free Press. USA Today. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Adams, Emily. "Walt Disney World Mini Golf". USA Today. studioD. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ "Disney's Magnolia" (PDF). Walt Disney World Golf. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ "River Country: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know About Disney's Abandoned Water Park". The Mouselets. August 16, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ Sandra Pedicini (June 30, 2015). "DisneyQuest closing at Downtown Disney". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Bevil, Dewayne; Palm, Matthew J. "Cirque du Soleil's 'La Nouba' to close at Disney". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ "Grand Floridian Construction Project". Laughing Place. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- ^ Bankhurst, Adam (September 30, 2021). "Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser Opening Date Revealed for Walt Disney World". IGN. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Wisel, Carlye. "Walt Disney World Just Announced a New Luxury Hotel". Travel + Leisure.

- ^ "Treehouse Villas To Be Replaced By New Treehouses At Walt Disney World". Netcot.com. February 12, 2008. Archived from the original on May 20, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Maehrer, Avery (January 11, 2021). "A Look Ahead at Walt Disney World Resort". Disney Parks Blog.

- ^ "Walt Disney World Tops Projection Of 10,000,000 Visitors In Its 1st Yr". Variety. October 11, 1972. p. 1.

- ^ Gabe, Todd (August 9, 2020). "Impacts of COVID-related capacity constraints on theme park attendance: evidence from Magic Kingdom wait times". Applied Economics Letters. 28 (14): 1222–1225. doi:10.1080/13504851.2020.1804047. ISSN 1350-4851.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2008 Global Attractions Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2009 Global Attractions Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2010 Global Attractions Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2011 Global Attractions Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2012 Global Attractions Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2013 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association/AECOM. 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ Rubin, Judith; Au, Tsz Yin (Gigi); Chang, Beth; Cheu, Linda; Elsea, Daniel; LaClair, Kathleen; Lock, Jodie; Linford, Sarah; Miller, Erik; Nevin, Jennie; Papamichael, Margreet; Pincus, Jeff; Robinett, John; Sands, Brian; Selby, Will; Timmins, Matt; Ventura, Feliz; Yoshii, Chris. "TEA/AECOM 2014 Theme Index & Museum Index: The Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association (TEA). Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2015 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

- ^ Au, Tsz Yin (Gigi); Chang, Bet; Chen, Bryan; Cheu, Linda; Fischer, Lucia; Hoffman, Marina; Kondaurova, Olga; LaClair, Kathleen; Li, Shaojin; Linford, Sarah; Marling, George; Miller, Erik; Nevin, Jennie; Papamichael, Margreet; Robinett, John; Rubin, Judith; Sands, Brian; Selby, William; Timmins, Matt; Ventura, Feliz; Yoshii, Chris (June 1, 2017). "TEA/AECOM 2016 Theme Index & Museum Index: Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2017 Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2019 Theme Index & Museum Index: Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "TEA/AECOM 2020 Theme Index & Museum Index: Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Russon, Gabrielle. "Disney's gondola system picks up $3.8 million worth of electrical work". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "Minnie Van™ Service". Walt Disney World.

- ^ "Lyft-Powered Minnie Van™ Service Launches at Walt Disney World". Lyft. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017.

- ^ "Disney World's Grand Opening". www.thisdayindisneyhistory.com.

- ^ "Disney Profile". Hospitality Online. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- ^ Grant, Rich (March 18, 2015). "How Walt Disney's Love of Trains Changed the World". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Conca, James (February 21, 2019). "Disney World Could Have Gone Nuclear". Forbes. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c Hiller, Jake (January 28, 2019). "Why Disney World Is Betting On Clean Energy". Forbes. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Sehlinger, Bob; Testa, Len (2014). The Unofficial Guide to Walt Disney World 2014. Birmingham, AL: Keen Communications. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9781628090000.

- ^ a b Mohney, Chris (2006). Frommer's Irreverent Guide to Walt Disney World. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing, Inc. p. 115. ISBN 9780470089880.

- ^ "New bag check areas greatly enhance Magic Kingdom arrival experience". Walt Disney World. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ^ "RCID Created". Reedy Creek Improvement. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ Foglesong, Richard E. (2003). Married to the Mouse. Yale University Press. pp. 69, 139. ISBN 978-0-300-09828-0.

- ^ Florida Supreme Court. Southern Reporter. Second Series. Alabama. Supreme Court, Alabama. Court of Appeals, Florida. Supreme Court, Louisiana. Courts of Appeal, Louisiana. Supreme Court, Florida. District Court of Appeals, Mississippi. Supreme Court. West Pub. Co.

- ^ Pastor, James F. (2006). Security Law and Methods. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 505–512. ISBN 978-0-7506-7994-7.

- ^ Louissant, Moise. "The Walt Disney Company: A Case Study in Private Security Trends". Fast Guard Service. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ^ Schweizer, Peter; Rochelle Schweizer (1998). Disney: The Mouse Betrayed: Greed, Corruption, and Children at Risk. Regnery Publishing. pp. 65–68. ISBN 978-0-89526-387-2.

- ^ Schwartzel, Eric (October 24, 2018). "Disney World's Big Secret: It's a Favorite Spot to Scatter Family Ashes". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Hooks, Danielle (September 8, 2017). "Disney World to close for fifth time in history in preparation for Hurricane Irma". WTKR-TV.

- ^ "Walt Disney World to close over coronavirus concerns". WESH. March 13, 2020. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Pallotta, Frank (March 12, 2020). "Walt Disney World closes, paralyzing the company's tourism empire". CNN Business.

- ^ Laughing Place Staff (May 27, 2020). "Live Blog: Walt Disney World Presents Reopening Plans to Orange County Economic Recovery Taskforce". Laughing Place. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Epstein, Jeffery; March, Ryan (May 19, 2020). "Welcome Back to Disney Springs". D23. The Walt Disney Company. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Parker, Ryan (July 31, 2021). "Disney to Mandate COVID-19 Vaccinations for All U.S. Staffers". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ "NASA Earth Observations Data Set Index". NASA. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

- Articles with short description

- Use mdy dates from March 2020

- Use American English from February 2017

- All Justapedia articles written in American English

- Coordinates not on Wikidata

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2020

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Articles needing additional references from September 2015

- All articles needing additional references

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2022

- Official website missing URL

- AC with 0 elements

- Walt Disney World

- 1971 establishments in Florida

- Amusement parks in Greater Orlando

- Amusement parks opened in 1971

- Buildings and structures in Lake Buena Vista, Florida

- Buildings and structures in Osceola County, Florida

- Resorts in Florida

- Tourist attractions in Orange County, Florida

- Tourist attractions in Osceola County, Florida

- Walt Disney Parks and Resorts