Battle of Toulon (1744)

| Battle of Toulon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Austrian Succession | |||||||

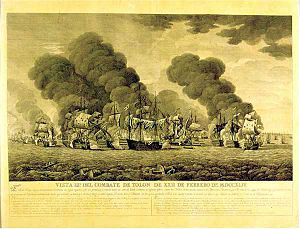

A Spanish illustration of the battle, Naval Museum of Madrid | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

27 ships of the line 3 frigates 3 smaller warships |

30 ships of the line 3 frigates 6 smaller warships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

149 killed, 467 wounded 3 ships damaged, 1 scuttled |

133 killed, 223 wounded, 17 captured [2] 5 ships damaged, 1 fireship sunk [2] | ||||||

The Battle of Toulon, also known as the Battle of Cape Sicié, took place between 21 to 22 February 1744 NS[a] near the French Mediterranean port of Toulon. Although France was not yet at war with Great Britain, ships from their Levant Fleet combined with a Spanish force, which had been trapped in Toulon for two years, to break the blockade imposed by the British Mediterranean Fleet.

The initial engagement on 21 February was largely indecisive and the British continued their pursuit until midday on 22nd before their commander, Admiral Thomas Mathews, called off the chase. With several of his ships in need of repair, he withdrew to Menorca, which meant the Royal Navy temporarily lost control of the waters around Italy and allowed the Spanish to take the offensive against Savoy.[3]

In his report, Mathews blamed his subordinate Richard Lestock for the failure and the issue was hotly debated in Parliament. At the subsequent court-martial, Mathews was held responsible and dismissed from the navy in June 1747, while Lestock's political connections meant he was cleared of all charges.[4] Another seven captains were removed from command for failing to engage the enemy and the investigation led to changes that required individual captains to be far more aggressive.

France declared war on Britain shortly after the battle but it led to recriminations with the Spanish, who suffered most of the casualties and complained of a lack of support. The French admiral, Claude Bruyère, was removed from command while the resulting ill-feeling limited further co-operation between the two sides.[5] The Spanish commander Juan José Navarro and his ships spent the rest of the war blockaded in Cartagena, Spain by Mathews' successor William Rowley.

Background

The immediate cause of the War of the Austrian Succession was the death in 1740 of Emperor Charles VI, last male Habsburg. This left his eldest daughter, Maria Theresa, as heir to the Habsburg monarchy, [b] whose laws excluded women from the succession. The 1713 Pragmatic Sanction waived this and allowed her to inherit, but this was challenged by Charles Albert of Bavaria, the closest male heir.[6]

While the House of Habsburg was the largest single component of the Holy Roman Empire, its pre-eminent position was challenged by rivals like Bavaria, Saxony and Prussia. With the help of France, these states turned a dynastic dispute into a European conflict and in January 1742 Charles of Bavaria became the first non-Habsburg Emperor in nearly 300 years. He was opposed by Maria Theresa and the so-called Pragmatic Allies, which in addition to Austria included Britain, Hanover and the Dutch Republic.[7]

Although French and British troops fought against each other at Dettingen in June 1743, the two countries were not yet formally at war. In contrast, Spain and Britain had been fighting the War of Jenkins' Ear since 1739, primarily in South America but also in the Mediterranean, where in 1742 a Spanish squadron led by Juan José Navarro took refuge in the French naval base of Toulon and were prevented from leaving by the British Mediterranean Fleet under Admiral Thomas Mathews. In the 1743 Treaty of Fontainebleau, Louis XV of France and his uncle Philip V of Spain, agreed to a joint invasion of Britain and by late January 1744, more than 12,000 French troops and transports had been assembled at Dunkirk.[8]

In an attempt to divert British naval resources from the invasion route, Navarro was ordered to force his way out of Toulon and make for the Atlantic, supported by the French Levant Fleet under Claude Bruyère. Their opponent, Thomas Mathews, had entered the Royal Navy in 1690 and enjoyed a solid if unspectacular career before being appointed Commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean in 1742. He had a poor relationship with his deputy Richard Lestock, a fact recognised by both officers who had each separately requested that Lestock be re-assigned, a request ignored by the Admiralty. The tension between the two men meant Mathews failed to properly discuss tactics with his subordinate prior to the battle, a factor which partially contributed to the later confusion over orders.[4]

Battle

On 21 February 1744, the combined Franco-Spanish fleet of twenty-seven ships of the line and three frigates put to sea with Mathews in pursuit. The British ships were generally larger and more heavily armed than their opponents, carrying over 25% more cannons overall.[9] Both fleets adopted the traditional formation of vanguard, centre and rear, with Navarro and the Spanish ships in front, followed by two French squadrons.[10] On the British side, Mathews led the van, William Rowley the centre and Lestock the rear.[11]

Light winds made manoeuvring difficult and caused the two fleets to become spread out but around 11:30 Early in the evening of 21 February, the fleets began to approach each other and prepare for battle, with Mathews signalling his ships to form line of battle.[12] The line had still not been properly formed as night fell, leading Mathews to hoist the signal to come to (halt by turning into the wind), intending for his ships to first finish forming the line.[12] The van and centre squadrons did so, but Lestock, commanding the rear, obeyed the order to come to immediately, without having formed the line.[12]

By daybreak on 23 February, the rear of the British fleet was separated by a considerable distance from the van and centre.[12] Mathews signalled for Lestock to make more sail, reluctant to start the attack with his ships still disorganised, but the slowness of Lestock to respond caused the Franco-Spanish force to start to slip away to the south.[12] Mathews feared that they would escape him and pass through the Strait of Gibraltar to join the French force gathered at Brest for the planned invasion of Britain.[12]

Knowing that his duty was to attack, Mathews hoisted the signal to engage the enemy aboard his flagship HMS Namur, and at one o'clock left the line to attack the Spanish rear, followed by Captain James Cornewall aboard HMS Marlborough.[12] In doing so, the signal to form the line of battle was left flying. The two signals flying simultaneously created confusion. A number of British commanders, including Captain Edward Hawke, followed Mathews' example, but many did not.[12] His other commanders were either too uncertain, or in the case of Lestock, unwilling to cooperate with him.[13]

Heavily outnumbered and unsupported, Namur and Marlborough managed to successfully engage their opposite numbers in the enemy line, but suffered considerable damage.[12] At the rear of the ships being attacked, five more Spanish ships followed, at some distance due to the slow speed of the one ahead: Brillante, San Fernando, Halcon, Soberbio and Santa Isabel. There was some exchange of fire between these and the lead ships of the English rear. Most of Lestock's ships in the rear remained inactive during the battle.[14]

The main action was being fought around Real Felipe, Navarro's flagship. Marlborough purposefully crossed the Spanish line, but suffered such severe damage that she was deemed to be on the verge of sinking. The Hercules, astern of the Real Felipe, vigorously fought off three British ships. The Constante, immediately ahead of the flagship, repelled the attack of a British ship-of-the-line, which was promptly replaced by two more, with which she continued to fight for nearly three hours.[14]

The French ships came about at 5 o'clock to aid the Spanish, a manoeuvre interpreted by some of the British commanders to be an attempt to double the British line and surround them.[12] The Spanish, still on the defensive, neglected to capture the defenceless Marlborough, though they did retake the Poder, which had previously surrendered to the British.[12] The Franco-Spanish fleet then resumed their flight to the southwest, and it was not until 23 February that the British were able to regroup and resume the pursuit. They caught up with the enemy fleet again, which was hampered by towing damaged ships, and the unmanoeuvrable Poder was abandoned and scuttled by the French. By now the British had closed to within a few miles of the enemy fleet, but Mathews again signalled for the fleet to come to. The following day, 24 February, the Franco-Spanish fleet was almost out of sight, and Mathews returned to Hyères and sailed from there to Port Mahon, where he arrived in early March.[12]

Aftermath

Tactically, the battle was indecisive while the invasion of Britain was abandoned soon after, but Mathews' withdrawal to Menorca temporarily lifted the blockade of the Gallispan army in Northern Italy, allowing them to take the offensive.[15] It also led to recriminations among the victors; Philip V of Spain made Navarro Marqués de la Victoria, or "Marquis of Victory", a title reflecting domestic opinion that the battle was a Spanish success negated by the poor performance of the French. He also insisted de la Bruyère be removed from command, while and the resulting ill-feeling minimised future co-operation between the two sides, while Navarro and his ships spent the rest of the war blockaded in Cartagena, Spain by Rowley, who had succeeded Mathews as commander in the Mediterranean.[5]

France declared war on Britain and Hanover in March, then invaded the Austrian Netherlands in May.[16] These were significant consequences, allegedly resulting from the failure of the British fleet to win a decisive action against an inferior opponent, [c] and Parliament demanded a public enquiry. At the subsequent court-martial, seven captains present at the battle were cashiered for failing to do their "utmost" to engage the enemy as required by the Articles of War, another two were acquitted while one died before trial.[d]. [18]

Mathews was also court-martialled on charges of having brought the fleet into action in a disorganised manner and failing to attack the enemy when the conditions were advantageous. Although his personal courage was not in question, he was found guilty of failing to comply with the official "Fighting Instructions" which required him to engage in "Line of battle", and dismissed from the navy in June 1747. Despite ignoring his commander's orders, Lestock was acquitted because in doing so he followed the precise letter of the instructions and was promoted Admiral of the Blue, although he died shortly afterwards in December 1746.[19]

The judgements were unpopular with the public, a contemporary declaring "The nation could not be persuaded...Lestock should be pardoned for not fighting, and Mathews cashiered for fighting".[20] His acquittal was largely due to his political connections, [4] and recognising the inquiry had been hampered by political and civilian interference, in 1749 Parliament updated the 1661 Articles of War to enhance the autonomy of naval courts. It also amended the section that read:

Every Captaine and all other Officers Mariners and Souldiers of every Ship Frigott or Vessell of War that shall in time of any fight or engagement withdraw or keepe backe or not come into the fight and engage and do his utmost to take fire kill and endamage the Enemy Pirate or Rebells and assist and relieve all and every of His Majesties Ships shall for such offence of cowardice or disaffection be tried and suffer paines of death or other punishment as the circumstances of the offence shall deserve and the Court martiall shall judge fitt.[21]

Article XII in the 1749 version was changed to permit the court far less discretion in terms of punishment, wording that would result in the 1757 execution of Admiral Byng.[22] It now read;

Every Person in the Fleet, who thro’ Cowardice, Negligence or Disaffection, shall in Time of Action withdrawn, or keep back, or not come into the Fight or Engagement, or shall not do his utmost to take or destroy every Ship which it shall be his Duty to engage, and to assist and relieve all and every of his Majesty's Ships, or those of his Allies, which it shall be his Duty to assist and relieve, every such Person so offending and being convicted thereof by the Sentence of a Court Martial, shall suffer Death.[23]

Notes

- ^ The dates of the battle were 21 to 22 February 1744 (New Style (NS)) according to the Gregorian calendar then used by France and Spain. The British still used the Julian calendar, which gave dates of 10–11 February 1744 (OS)

- ^ Often referred to as 'Austria', this included Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, the Austrian Netherlands, and Parma

- ^ Modern historians argue these actions had been agreed in October 1743 and were unaffected by Toulon [17]

- ^ These were; (1) George Burrish; HMS Dorsetshire (2) John Ambrose; HMS Rupert (3) Edmund Williams; HMS Royal Oak (4) Richard Norris; HMS Essex (5) Thomas Cooper; HMS Stirling Castle (later restored) (6) James Lloyd; HMS Nassau (7) William Dilkes; HMS Chichester

References

- ^ Wilson & Callo 2004, p. 268.

- ^ a b Allen 1842, pp. 327, 329.

- ^ Dull 2009, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Baugh 2004.

- ^ a b Anderson 1995, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Anderson 1995, p. 3.

- ^ Black 1999, p. 82.

- ^ Harding 2013, p. 171.

- ^ Allen 1842, p. 325.

- ^ Allen 1842, p. 324.

- ^ Allen 1842, pp. 323–324.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Mathews, Thomas (1676–1751)". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 37. p. 45.

- ^ Lecky, William Edward Hartpole (1892). A History of England in the Eighteenth Century. London: Longmans, Green. p. 19.

- ^ a b Martínez-Valverde, Carlos (6 October 2005). "La batalla de Cabo Sicié (Tolón), 1744". Todo a babor (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ Dull 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Lindsay 1957, p. 430.

- ^ Anderson 1995, p. 130-132.

- ^ Beatson 1788, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Bruce 1998, p. 224.

- ^ Hervey 1779, p. 270.

- ^ 'Charles II, 1661: An Act for the Establishing Articles and Orders for the regulateing and better Government of His Majesties Navies Ships of Warr & Forces by Sea.', Statutes of the Realm: volume 5: 1628–80 (1819), pp. 311–314. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=47293 Date accessed: 8 June 2010.

- ^ Ware 2009, pp. 151–53.

- ^ 'Admiral Byng's defence, as presented by him, and read in the Court January 18, 1757,... Containing a very particular account of the action on the 20th of May, 1756, off Cape Mola,...' John Byng, 1757, pp. 10–11.

Sources

- Allen, Joseph (1842). "Admirals Mathews and Lestock". United Service Magazine.

- Anderson, M.S (1995). The War of the Austrian Succession 1740-1748. Longman. ISBN 978-0582059511.

- Baugh, Daniel (2004). "Mathews, Thomas(1676–1751)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18332. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Beatson, Robert (1788). A political index to the histories of Great Britain and Ireland. J.J.Robinson.

- Black, Jeremy (1998). Britain as a military power 1688–1815. UCL Press. ISBN 978-0-203-17355-8.

- Black, Jeremy (1999). From Louis XIV to Napoleon: The Fate of a Great Power. Routledge. ISBN 978-1857289343.

- Browning, Reed (1995). The War of the Austrian Succession. Griffin. ISBN 978-0312125615.

- Bruce, Anthony (1998). An encyclopedia of naval history. Dearborn Press. ISBN 978-1579581091.

- Dull, Jonathan R (2009). The Age of the Ship of the Line: The British and French Navies, 1650–1815 (Studies in War, Society, and the Military). University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803219304.

- Harding, Richard (2013). The Emergence of Britain's Global Naval Supremacy: The War of 1739–1748. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843838234.

- Lindsay, J.O, ed. (1957). The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol VII; The Old Regime 1713–63. CUP. ISBN 0-521-04545-2.

- Hattendorf, John: Naval policy and strategy in the Mediterranean: past, present, and future. Taylor & Francis, 2000, ISBN 0-7146-8054-0

- Hervey, Frederick (1779). The Naval, Commercial, and General History of Great Britain, Volume IV (2018 ed.). Creative Media. ISBN 978-1385772720.

- Clowes, W. Laird. The Royal Navy : a history from the earliest times to the present, Vol III. London : S. Low, Marston and Company (1897).

- O'Donnell, Duque de Estrada y Conde de Lucena, Hugo (2004). El primer Marqués de La Victoria, personaje silenciado en la reforma dieciochesca de la Armada (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. ISBN 84-96849-08-2.

- Ware, Chris (2009). Admiral Byng: His Rise and Execution. Pen and Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84415-781-5.

- Wilson, Alastair; Callo, Joseph F (2004). Who's Who in Naval History, From 1550 to the present. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415308281.

Further reading

- Browning, Reed. The War of the Austrian Succession. Alan Sutton, 1994.

- Rodger N. A. M. Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815. Penguin Books, 2006.

- Roskill, Stephen Wentworth: H. M. S. Warspite: the story of a famous battleship. Collins, 1957.

- Waldegrave Head, Frederick: The fallen Stuarts. Issue 12 of Cambridge historical essays. Prince consort prize essays. Cambridge University Press, 1901.

- White, Henry: History of Great Britain and Ireland. Oxford University, 1868.

- Williams Damer Power, John: Bristol privateers and ships of war. J. W. Arrowsmith Ltd., 1930.

- Garner Thomas, Peter: Politics in eighteenth-century Wales. University of Wales Press, 1998. ISBN 0-7083-1444-9

- Crofts, Cecil H.: Britain on and Beyond the Sea – Being a Handbook to the Navy League Map of the World. Read Books, 2008. ISBN 1-4437-6614-3

- Willis, Sam: Fighting at sea in the eighteenth century: the art of sailing warfare. Boydell Press, 2008. ISBN 1-84383-367-0

External links

Media related to Battle of Toulon (1744) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Toulon (1744) at Wikimedia Commons- La campaña de don Juan José Navarro en el Mediterráneo y la batalla de Sicié (1742–1744) (in Spanish)

- CS1 Spanish-language sources (es)

- Articles with short description

- Use dmy dates from June 2013

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using cite ODNB with id parameter

- Commons category link is defined as the pagename

- Articles with Spanish-language sources (es)

- Coordinates not on Wikidata

- AC with 0 elements

- Conflicts in 1744

- Naval battles of the War of the Austrian Succession

- Naval battles involving Great Britain

- Naval battles involving France

- Naval battles involving Spain

- Var (department)

- Toulon

- 1744 in France