Waltham Watch Company

| |

| Industry | Watchmaking and Clockmaking |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1850 |

| Headquarters | |

| Products | Watches, clocks & aircraft clocks |

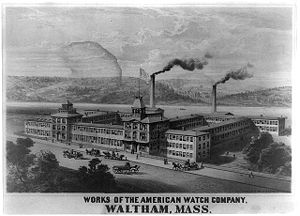

The Waltham Watch Company, also known as the American Waltham Watch Co. and the American Watch Co., was a company that produced about 40 million watches, clocks, speedometers, compasses, time delay fuses, and other precision instruments in the United States of America between 1850 and 1957. The company's historic 19th-century manufacturing facilities in Waltham, Massachusetts have been preserved as the American Waltham Watch Company Historic District.

The company went through a series of bankruptcies and restarts under new ownership, with watches and clocks bearing the Waltham name still being made and marketed today.

History

The early years, 1849 to 1857

Prior to 1850, watches in America were generally supplied either from England or Switzerland.[1] The idea for the Waltham Watch Company came from watchmaker Aaron Lufkin Dennison. Dennison was the son of a shoemaker, born in Maine in 1812.[2] He served as an apprentice to a jeweler for three years as a youth and had come to Boston in 1833.[2] In 1833 he became a journeyman watchmaker with the firm of Currier & Trott in Boston, leaving in 1839 to go into business for himself.[3]

Mass production of clocks had come on line during the first quarter of the 19th century in the United States, moving from a handicraft to a factory basis; the forward-thinking Dennison hoped to apply the same principles and techniques to the making of pocket watches.[1] This would not be his first venture, however. In 1844 Dennison started the firm that would later emerge as the Dennison Manufacturing Company, a paper box business. He found this enterprise distracted him from his dream of industrial production of watches and turned the company over to brother Eliphalet Dennison in 1849 so that he could turn his full attention to horology.[4]

In 1849, Dennison was approached by Edward Howard, a clock and scale maker from Boston. Howard initially wanted Dennison to build locomotives but instead went into business with Dennison making watches. Joining Dennison and Howard in establishment of the company were fellow Bostonians David P. Davis, experienced in manufacturing, and financial angel Samuel Curtis.[2] Initial funding of $20,000 was raised[3] and the American Horological Company was born.

Dennison, paid $1,200 a year to head the project, was sent to Great Britain by his partners to learn trade secrets and purchase supplies for the American effort.[1] Dennison observed that the watch industry in England was not highly mechanized and believed the new American firm by he and his partners could make an impact in the watch industry.[1]

The company began with construction of a 100-foot long brick building on land in Roxbury, Massachusetts already owned by partners Howard and Davis.[5] Specialized machinery was designed and the flow of daily operations perfected.[6] "The firm attracted an able staff well versed in the field of watchmaking and willing to experiment with new methods," one historian of the firm later observed.[1] Both Swiss and American watchmakers were employed.[3]

Unfortunately, the company's first offering, an innovative model which ran for eight days without winding, was a commercial failure, with about 900 pieces produced. A second, more conventional model with a 36-hour power reserve was put into production and met with success in the marketplace.[6]

The Roxbury factory was soon deemed to be too small for efficient mass production.[6] Dennison sought a rural locale for the new facility and the town of Waltham, Massachusetts was chosen.[6] Local residents contributed funds for land and improvements through a development company established by Dennison, the Waltham Improvement Company.[6] One hundred acres of land were purchased and a building constructed, with operations commencing in 1854.[6] There were 90 workers at the factory at the time of its inception, with total output of 30 watches per week.[6]

in 1855 the company name was changed once again, this time to The American Waltham Watch Company.[7]

The economics of production on this scale proved untenable. To cover the deficit in watch company operations in 1856 $6,000 in notes guaranteed by the Waltham Improvement Company were issued.[8] The situation further deteriorated with the coming of an economic crisis in the third quarter of 1856.[8] As the economy stalled, Waltham's watch sales plummeted. The partners contributed their personal savings in an effort to save the company, with an additional $20,000 raised by selling exclusive selling rights to Waltham watches to a large wholesale jeweler in New York City.[8] This effort was insufficient and at the end of February 1857 the Waltham Improvement Company foreclosed on the mortgage it held for the Waltham factory.[8] Assets were distributed in a sheriff's auction, with the Waltham property purchased by Royal E. Robbins for $56,000.[8]

Although founder Dennison remained as superintendent of the Waltham facility until 1862, the initial phase of the Waltham Watch Company had come to an end.[9]

The Civil War period, 1857 to 1865

New owner Royal Robbins was an experienced New York watch importer who worked a partnership with his brother Henry Asher Robbins and Daniel F. Appleton in an effort to make the Waltham Watch operation a success. All three members of this troika had extensive experience in the watch sales and the jewelry trade.[10] Administration of the company was measured and prudent and the economic crisis of 1857 was survived.

With the coming of the American Civil War in 1861, the American economy began to boom. Demand for watches expanded markedly, with soldiers in particular eager to obtain a reasonably-priced timepiece for their personal use.[9] To meet this demand, Waltham Watch unveiled a comparatively inexpensive $13 model called the "William Ellery."[9] This watch was a "fad" among Union soldiers and sales blossomed. By the end of the Civil War the Ellery represented fully 45 percent of Waltham's annual sales.[11]

The Period of Growth, 1866 to 1906

After the Civil War, the company became the main supplier of railroad chronometers to various railroads in North America and more than fifty other countries. In 1876, the company showed off the first automatic screw making machinery and obtained the first gold medal in a watch precision contest at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.

In 1885 the company name changed to the American Waltham Watch Company (AWWCo).

Decline, diversification, and restructuring, 1907 to 1922

Waltham's profitability was greatly impacted by the Panic of 1907, which brought a rapid fall of sales and earnings.[12] This downturn not only did not abate but actually accelerated in 1908 and 1909, leading the sons of Royal Robbins to liquidate their holdings in the company as quietly as possible, with the brothers selling nearly all of the Waltham stock which they had inherited from their father.[12] Stockholder became aggrieved by the company's flagging fortunes and voted to terminate an existing sales relationship with the company Robbins & Appleton,[13] an independently owned wholesale arm which contracted to dispose of the entire output of Waltham on a 6% commission. Four longtime members of the company's board of directors resigned and new directors appointed.[13]

Board member Augustus P. Loring became the effective leader of Waltham's majority shareholders in 1910.[14] In an economizing measure a vice-presidential position was cut and executive pay generally reduced by the new board majority.[15] A further effort was made to infuse new blood into Waltham's management corps in an effort to break up a privileged and lethargic executive bureaucracy, although this change was met with only limited success.[16]

The company attempted to diversify its output. Seeing a great demand in Europe as a result of the outbreak of World War I, Waltham introduced production of mechanized time fuses to control the burst of artillery shells in 1915, as well as automobile speedometers in 1916 and blood pressure gauges in 1917.[17] Wholesale sales were taken in-house rather than being contracted out.[18]

Waltham found itself pouring time and effort into the task of developing and improving a timing device which could absorb the shock of being fired from heavy artillery and its ability to design and manufacture conventional timepieces consequently suffered.[19] By 1917 the American economy was booming, demand for watches was high, but Waltham was operating at full capacity, with the United States War Department calling for increased production of artillery fuses.[19] Other American watchmakers were content limiting themselves to production of ordinary chronometers; with no experience making artillery fuses, contracts and production fell overwhelming upon Waltham's shoulders.[20]

In the short term, Waltham prospered through its emphasis on military contracts, with sales nearly doubling between 1915 and 1918 and earnings soaring by 156%.[21] However the easy money of military contracts papered over what one historian has characterized as an era of "wanton extravagance, gross inefficiency, and a marked lack of business foresight."[22] With the end of the war came the Depression of 1920–1921, drying up military and consumer sales alike.

Waltham was a bloated behemoth, divided into watertight departments operated with a minimal eye to coordination and cooperation.[23] A panel of consultants employed by management were shocked to discover 25 rival departments within the company, with "each foreman operating his department as though it were a plant in itself," determining its own production and hiring its own personnel.[24] The company was massively overstaffed, with the consulting engineers indicating that 4,000 people were currently employed to do the work that 2,000 efficiently used workers were capable of achieving.[24] Unsold inventory ballooned to $11 million, while the company racked up $8 million in debt, while being forced to pay dividends on a substantial quantity of stock.[25]

With the coming of price deflation in 1921, banks tightened their credit policies. Lending banks came to realize that Waltham's loans were not adequately covered by current assets.[25] Information about Waltham's inefficient model of organization also undermined lender confidence.[26] Waltham's external financiers worried that shutting off credit entirely might force Waltham into liquidation and default upon their original loans. A period of negotiation was begun, in which lenders successfully demanded that Waltham's management be brought under their own direct control.[27]

Regarding Waltham's management as incompetent, the First National Bank of Boston and other creditors took effective control of the company late in 1921, selecting one of their own directors, Gifford K. Simonds of Fitchburg, Massachusetts as new chief executive officer.[27] The manager of a mid-sized family-owned sawmill for a decade,[28] Simonds threw himself into learning the watch business, visiting every part of the plant and working three months behind a retail counter to learn about consumer preferences and expectations.[29]

Fighting for freedom of action against entrenched interest groups, including bankers, stockholders, managers, and workers, Simonds sought to instill discipline, speed up the production process, and lay off superfluous workers, cutting payroll by 1,000.[30] He believed that unsold inventory was severely overvalued on the company's books, leading to a write-down assets by $3 million and a dumping unsold inventory on the market.[31] Cutting benefits and speeding up production norms, Simonds managed to reduce the production cost by 25% and to eliminate $800,000 of the company's debt by January 1923.[32] This proved insufficient for troubled lenders, however, and in February 1923 creditors had found a new underwriter and Simonds' brief tenure drew to a close.

The wristwatch era, 1923 to 1940

Waltham was reorganized in 1923 by a syndicate headed by the investment firm of Kidder, Peabody and Co.[33] Kidder, Peabody drove a hard bargain, forcing through a two-tiered financial overhaul in which large investors able to contribute new money for the purchase of preferred stock were able to convert old common stock for newly issued common stock at the rate of 10 shares for 9.[34] These monied investors were also able to convert their old interest-bearing preferred stock to new at the rate of 10 shares for 8.[34] Small investors unable to contribute new money were treated far less favorably, however, being forced to accept an exchange of old stock for new at the rate of 10 shares for 2.5 — thereby losing 75% of their equity in one fell swoop.[34] Financial institutions and large investors thus saw their stake in the reorganized firm protected, while small investors absorbed the brunt of the inevitable write-down of company value.

Kidder-Peabody benefited handsomely as underwriter of securities and investor in preferred stock, realizing nearly $2.5 million in profit, dividends, and capital gain from the sale of stock over the 1923–28 period.[35]

A charismatic new chief executive came in as part of the restructuring, F. C. Dumaine, who arrived at Waltham to lead the new regime in February 1923.[36] The former "gargantuan collection of small workshops" was integrated,[37] and production steered towards more marketable products. Company debt was paid down. This restructing proved profitable, and the price of Waltham stock subsequently advanced impressively, easing the company's credit burden.[33]

The restructured company of 1923 began its run on the precipice of disaster. A fairly vast part of unsold inventory took the form of partially completed timepieces, a substantial part of which could not be readily disposed of except as scrap.[38] Foremen had kept their departments running at full capacity regardless of actual demand for the components produced, resulting in gluts of jewels, lubricating oil, steal, and brass, while other components remained in short supply.[39] Some items were overproduced to such great extent that available stocks were projected to last for 20 years or more.[39]

Moreover, Waltham was slow to adapt to the desires of a changing marketplace, with postwar consumers demanding an overwhelming proportion of small wristwatches, for which Waltham lacked stylistic prowess or physical machinery.[40] The company remained geared towards the production of high-grade pocket watches. Competition had made itself felt, with rivals Elgin and Hamilton increasing their capitalization and modernizing their plant, while imports from Switzerland increased nearly 500% between 1913 and 1920.[41] Economic recovery in 1922 had left Waltham behind, with fully two-thirds of the plant left idle.[40]

Dumaine's efforts at rationalization of Waltham began with a reduction of executive salaries, which had topped $100,000 a year for top level executives in the previous period.[42] Private secretaries were eliminated and a smaller secretarial office pool established instead.[43] No general reduction of salaries was attempted for office and factory workers but total payroll was nonetheless reduced through layoffs and reorganization, with an eye to streamlining the company's inefficient planning and billing bureaucracy.[43]

In the words of one study of the company's business management practices:

- "The saving in money — about a thousand dollars a day — was important, but the effect on methods and morale was of greater consequence. This initial campaign demonstrated at once, and for all time, that direct and simple methods would be used; also that every employee must earn his wages, not merely in effort expended, but also in results accomplished.[43]

Most importantly, Dumaine changed the company's course from the production of the elegantly-crafted pocket watches for which it was known — a form increasingly out of favor with post-war consumers — towards the manufacture of smaller and fresher wristwatches designed for a mass market at a lower price-point.[44] This change had come with significant risk, as Waltham had dominated the market for luxury pocket watches and faced a serious shortage of the designers and toolmakers needed to revamp and modernize its product line.[45] There was even doubt whether American factory production could be adapted to take on the finely-detailed and well crafted product produced by the Swiss at a lower average wage rate.[46]

Dumaine also took aim at Waltham's pricing policy, which had previously varied with market conditions to achieve as high a price as possible.[46] Waltham's products were consequently priced for between 15 and 25% more than equivalent products of rival companies when the new company regime took the helm in 1923.[46] Still seeking the cachet of a top shelf price, Dumaine nevertheless immediately lowered the selling prices of the company's products to a point just 5% higher than the comparable goods of its domestic competitors.[46] This proved to be a first step to true parity with the prices of the company's main American competitors, Elgin and Hamilton.[47]

Watchmakers' Strike of 1924

The company turned to a general wage cut of 10 to 40% to bolster profitability in 1924.[48][49] This, unsurprisingly, proved unpopular with Waltham workers, 75 of whom in the Finishing department put down tools on August 11, 1924, over news of a forthcoming 10% wage cut.[50] The spirit of militance spread and the next day, slated to be the first of the new wage scale, fully 200 workers from the Finishing and Setting-Up departments stayed home.[51] Within three days the entire Waltham plant was embroiled in a company-wide work stoppage, the first in the more than 70-year history of the company.[52]

As part of the strike, former department-level worker organization within Waltham was abandoned and a new organization called the Watchmakers Protective Association established.[53] Affiliation of this new company-wide union with the American Federation of Labor was anticipated.[51]

Plant superintendent I.E. Boucher refused to meet with organized workers in connection with the strike, only individuals, further exacerbating the conflict.[51] Moreover, Boucher declared that striking workers would be no longer considered employees of Waltham and that each must individually apply for reemployment through the company's employment office.[53] On the third day, other departments shut down over the company's unilateral wage cut, with 2,000 of Waltham's 2,900 total employees hitting the street over the reduction.[52] A parade estimated at 2,000 people, including some workers with 50 years of company service, marked through the streets of Waltham to a rally held at the city park.[52] The only department which remained in operation after the third day was the Machine department, whose employees were members of a separate AF of L-affiliated union and who were awaiting approval of their national organization to join the work stoppage.[54] Packing clerks and stenographers joined the strike in sympathy during the second week, effectively halting operations of the Waltham plant.[55]

As August ended the two sides remained deadlocked over the wage scale. More mobile workers began to leave the city, going to Elgin, Illinois or Lancaster, Pennsylvania to seek employment with Waltham's chief domestic competitors.[56]

In September a union proposal accepting wage reductions for men making more than $40 a week or women making more than $20 — thereby exempting the lowest paid workers from the cutback.[57] Company acceptance was expected and a celebratory was held on Saturday, September 27.[58] When news came of the company's rejection of the compromise proposal, in favor of a counteroffer of a general 7.5% wage cut, the party turned into a riot, with a mob of thousands storming the company's gates.[59] Police intervention broke up the melee in the wee hours of Sunday morning.[58]

The rejection of the compromise proposal marked a turning point in the strike, as strikers became more aggressive towards strikebreakers who crossed their picket lines, hurling abuse and stones and waving yellow handkerchiefs at the defectors.[60] Vacations were canceled for the Waltham police force and police presence was increased in the aftermath of the threatened violence.[60]

The strike continued into October, when the Massachusetts State Board of Conciliation, after a lengthy fact-finding process, proposed a 5% wage cut as justified for all workers earning more than $18 a week.[61] This proposal satisfied no one, with Waltham management politely refusing to move off their proposal for a general reduction of 10% and strikers holding a mass meeting which lent no support to the board's report.[62]

The company was able to maintain operations through the use of strikebreakers, primarily new hires and the strike continued through then end of 1924.

World War II and after, 1941–1957

During World War II Waltham was an important contractor for the American military, producing timepieces for service personnel and timing devices for military ordinance.

The post-war years were not kind to Waltham, however. The company closed its factory doors and declared bankruptcy in 1949, despite noble efforts by machinist George B. Peel, who'd invented an unbreakable mainspring. Although the factory briefly reopened a few times, primarily to finish and case the existing watch inventory for sale. Several different plans were presented to restart the business, but all failed for various reasons.

Waltham of Chicago, 1959 to 1967

In 1957 Waltham decided to leave the consumer watch business. The former Waltham company was reorganized as the Waltham Precision Instruments Company, a maker of speedometers and electronic parts for the automotive and aviation industry. President Joseph Axler retained control of the Waltham name, which he sold to Harold B. "Harry" Aronson, president of the Hallmark Watch Company, in the spring of 1959.[63] Hallmark had previously held a contract to assemble and market Waltham products under license.[63]

The officers of Hallmark took over similar positions in the reorganized Waltham. The board consisted of Harold B. "Harry" Aronson (president), Ben Cole, and Morris Draft, formerly officers of Hallmark.[64] Chicago attorney Seymour Rady was a vice president and the company's chief counsel from 1957 until his death in December 1966.[65] At the end of 1959 Aaron Thorne, a former Western regional sales manager for Benrus Watch Company was added as a vice president, working from an office in Los Angeles. Thorne supervised sales to the Western United States and Asia.[66]

The new company moved its base of operations from Massachusetts to Chicago. An important change was made in the company's business model, with a move to franchised distributors who would pay about $1200 up front to the company in exchange for display cases and inventory to be placed in local drug stores, hardware stores, and appliance stores. Hundreds of newspaper ads were placed around the country to publicize the venture, which was headquartered in New York under the name Time Industries. Franchisees were to maintain inventory in these cases, splitting proceeds with the business owners in which the cases were placed.[67] This change signified a new emphasis upon lower-end, more popularly priced products.

The new company also moved to license its well-known and respected name to others. In the fall of 1963 Waltham signed a licensing agreement with the Samson Company of Chicago to manufacture transistor radios and tape recorders bearing the Waltham logo.[68]

Production of the complicated inner watch movements was moved out of the United States. Waltham opened a new factory in Neuchatel, Switzerland in the summer of 1962 designed to produce up to 100,000 watch movements per month.[69]

The company came under much scrutiny by the Federal Trade Commission throughout the 1960s, accused of misrepresenting the number of jewels within its watches, pre-tagging merchandise with inflated prices bearing no connection to actual prices charged, and misrepresenting country of origin and connection of the new company to the previous Waltham Watch Co. It was forced to change its advertising and branding policies in response to these complaints.[70]

Waltham was a very successful enterprise throughout its Chicago period with total sales jumping from about $10.5 Million in 1962 to $12.1 Million in 1963, and net income increasing by 70%. Improvement in efficiency and higher gross margins were credited for the up-tick in profitability.[71] Sales and profits increased again in 1964, with total sales hitting the $13.3 Million mark and net income up another 35%.[72]

Waltham emerged as a leading maker of dive watches, a segment which sold over 200,000 pieces in the United States in 1967. The company made a 5 bar hand-winding model priced at $50 and a deluxe version good to 300 feet for serious divers retailing for $120.[73]

Sale to new Swiss ownership, 1968 to 1980

In March 1968, Waltham President Harry Aronson announced that a Swiss group headed by the Invicta Watch Co. had agreed to in principle purchase Waltham, a publicly-held company whose shares were sold over the counter.[74] A formal offer to buy shares of Waltham common stock at $16 per share was announced in September 1968. Purchaser was a Delaware-registered entity called Iseca, headed by Invicta Watch Company of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, but also including H. Sandoz & Co. of La Chaux-de-Fonds, and Degoumois & Co. of Neuchatel, Switzerland.[75] Iseca's purchase was of 283,976 shares, of which 151,819 were held by a group headed by company president Harry B. Aronson.[75] Aronson was retained under terms of the deal as a consultant for six years at $30,000 per year.[75] A total of just over $6.5 million cash were to be used in the acquisition, financed by sale of Iseca capital stock and a $3.9 million loan from the Union Bank of Switzerland.[75] According to the published Sept. offer, "Iseca does not presently have any plan to liquidate Waltham, or to sell its assets to, or merge it with, any other persons, or to make any other major change in Waltham's business or corporate structure."[75]

Management was changed with the purchase of Waltham by Invicta, with Georges Didisheim, president of Invicta Watch Co., named chairman and Morris Draft executive vice president in August 1968. The company remained headquartered in Chicago.[76]

There are also some Waltham watch models that have been brought to Invicta. In those years Waltham started to produce a watch line, especially for Invicta. This was called “Invicta by Waltham”. In some cases, both Invicta and Waltham were on the dial. Other cases will only show a “W” to indicate that this watch was manufactured by Waltham for Invicta.

Later in the 1970s, Waltham was merged into a federation with other Swiss makers of inexpensive watches, the Société des Garde-Temps SA (SGT). Georges Didisheim remained chairman of the board of Waltham following this merger.[77]

Concentrating on manufacturing watches for a lower retail price point, sales blossomed, with quantity of watches sold doubling between 1968 and 1975, to a total of more than one million pieces annually.[77] This made Waltham the third largest watchmaker in America by 1975, behind Timex and Bulova.[77] Sales were sufficient to move to a new larger facility in Chicago, a 100,000 square foot building formerly owned by the American Can Company.[77]

In January 1974, Société des Garde-Temps purchased rights to the name of the Elgin Watch Company, another storied American brand.[77]

Waltham in the Quartz era, 1981 to date

As a result of the quartz crisis, SGT terminated operations in 1981. The rights to the names of the various SGT brands were sold individually.[78]

The Waltham brand name was purchased by the Japanese firm Heiwado & Co. and soon emerged as the most popular brand in Japan.[79]

In 2011 a majority stake in Waltham International SA was sold to Italian-American entrepreneur Antonio DiBenedetto.[79]

Legacy

Before the Waltham Watch Company went out of business in 1957, it founded a subsidiary in Switzerland in 1954, Waltham International SA. Waltham International SA retains the right to the Waltham trade name outside of North America, and continues to produce mechanical wrist watches and mechanical pocket watches under the "Waltham" brand.

During their restructuring efforts in the 1950s, Waltham opened an office in New York for the purposes of importing Swiss watch movements and cases. Due to restrictions placed on the company by its main creditor, the Restructuring Finance Corporation, they could not sell these watches directly, so they were sold through an independent company, the Hallmark Watch Company.

Specialized clocks and chronographs for use in aircraft control panels continued to be made in the Waltham factory by the Waltham Precision Instruments Company. In February 1994, Prime Time Clocks purchased the last remaining product line, the mechanical aircraft clock.[citation needed] Waltham Precision Instruments was moved to Ozark, Alabama and changed its name to Waltham Aircraft Clock Corporation.[citation needed]

Historical resources

Every watch movement that the company produced through the early 1950s was engraved with an individual serial number. That number can be used to estimate the date of production. Volunteers have created a database of Waltham serial numbers,[80] models and grades,[81] and descriptions of observed watches.[82]

The archive of the Waltham Watch Company is housed by Baker Library Special Collections department of the library of Harvard Business School, Harvard University. The material, which includes company books primarily from 1854 to 1929, is contained in 52 archival boxes, totaling 111 linear feet.[83]

See also

- American system of watch manufacturing

- Benrus Watch Company

- Bulova Watch Company

- Elgin Watch Company

- Gruen Watch Company

- Hamilton Watch Company

- Illinois Watch Company

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e Caross, "The Waltham Watch Co.," p. 167.

- ^ a b c Caross, "The Waltham Watch Co.," p. 166.

- ^ a b c "Yankee Hod-Carrier Revolutionized the Making of Watches". The Independent-Record. 28 February 1895. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Caross, "The Waltham Watch Co.," pp. 166–167.

- ^ Caross, "The Waltham Watch Co.," pp. 167–168.

- ^ a b c d e f g Caross, "The Waltham Watch Co.," p. 168.

- ^ Harry Chase Brearley, Time Telling Through the Ages. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1919; pp. 241-243.

- ^ a b c d e Caross, "The Waltham Watch Co.," p. 169.

- ^ a b c Caross, "The Waltham Watch Co.," p. 170.

- ^ Caross, "The Waltham Watch Co.," pp. 169–170.

- ^ Carlene Stephens, "A Close Look at the Pocket Watch of a Civil War Surgeon," The Atlantic, August 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Charles W. Moore, Timing a Century: History of the Waltham Watch Company. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1945; p. 92.

- ^ a b Moore, Timing a Century, p. 95.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 100.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 102.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 103.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 106.

- ^ a b Moore, Timing a Century, p. 107.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 108.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 110.

- ^ Charles W. Moore in Moore, Timing a Century, p. 111.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 114.

- ^ a b Moore, Timing a Century, p. 115.

- ^ a b Moore, Timing a Century, p. 116.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Moore, Timing a Century, p. 117.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 119.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 126.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, Chapter 7, passim.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 123, 125.

- ^ a b Basil Manly, "New Tariff Bill to Send Watch Prices Soaring," Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer, Sept. 1, 1929, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 149.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 160.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 136.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 139.

- ^ a b Moore, Timing a Century, p. 131.

- ^ a b Moore, Timing a Century, p. 135.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 134–135.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 162.

- ^ a b c Moore, Timing a Century, p. 163.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, p. 164.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b c d Moore, Timing a Century, p. 165.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 166.

- ^ The cut was framed by the company as a 10% general wage cut, with strikers contending that the actual proposed reduction ranged from 10 to 40 percent, with an average cut of about 25%. See: "More Employees Quit Watch Co," Boston Globe, Aug. 13, 1924, p. 4.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 171.

- ^ "75 Waltham Watch Co Finishers Go On Strike," Boston Globe, Aug. 11, 1924, p. 18.

- ^ a b c "Waltham Watch Co Workers on Strike," Boston Globe, Aug. 12, 1924, p. 11.

- ^ a b c "More Employees Quit Watch Co," Boston Globe, Aug. 13, 1924, p. 4.

- ^ a b "1600 More Join Waltham Strike," Boston Globe, Aug. 13, 1924, p. 11.

- ^ "To Hold Parley in Watch Strike," Boston Globe, Aug. 14, 1924, p. 13.

- ^ "Watches," Buffalo Evening News, Aug. 21, 1924, p. 14.

- ^ "No Sign of Either Side Giving In," Boston Globe, Sept. 3, 1924, p. 5.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b "Strikers Massed at Gate," Barre [VT] Daily Times, Sept. 29, 1924, p. 1.

- ^ Moore, Timing a Century, pp. 172.

- ^ a b "Waltham Crowd is Threatening," Boston Globe, Sept. 30, 1924, p. 15.

- ^ "Urges 5 Percent Cut at Waltham," Boston Globe, Oct. 11, 1924, p. 13.

- ^ "Not to Act Now on Peace Plan," Boston Globe, Oct. 12, 1924, p. 14.

- ^ a b "Harry Aronson Heads Waltham Watch Co.," Boston Globe, March 31, 1959, p. 43.

- ^ "Waltham Watch Firm Ordered To Halt Claims," York [PA] Gazette and Daily, Dec. 1, 1962, p. 2.

- ^ "Seymour Rady, Hightland Park Attorney, Dies," Chicago Tribune, Dec. 8, 1966, Section 1C, p. 16.

- ^ "Business and People," Los Angeles Times, Dec. 31, 1959, section 1, p. 8.

- ^ See, for example, "Rare Business Opportunity," Rocky Mount [NC] Telegram, Feb. 8, 1959, p. 4D.

- ^ "Sampson Signs License Pact With Waltham," Chicago Tribune, Nov. 23, 1963, p. 49.

- ^ "New Waltham Watch to Run by Radio Waves," Chicago Tribune, March 27, 1962, p. 47.

- ^ "Waltham Precision Instruments vs Federal Trade Commission". OpenJurist. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ "Waltham's Net in Year Jumps 70%," Chicago Tribune, May 18, 1964, section 3, p. 8.

- ^ "Waltham Net Hits Record; Vote Dividend," Chicago Tribune, April 12, 1965, section 3, p. 13.

- ^ "Skin Diver Watches: The Latest Masculine Fashion Trend," West Side Index [Newman, CA], June 20, 1968, p. 2.

- ^ "Swiss Group to Make Offer for Waltham," Chicago Tribune, March 31, 1968, section 4, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e "Offer to Purchase Common Stock of Waltham Watch Company," Chicago Tribune, Sept. 4, 1968, sec. 3, p. 8.

- ^ "People," Chicago Tribune, Aug. 29, 1968, section 3, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e William Gruber, "Waltham Watch Ticking Happily in Larger Plant," Chicago Tribune, Sept. 30, 1975, p. 53.

- ^ Treub, Lucien F. (1999). Die Zeit der Uhren. Ebner Verlag. ISBN 3871880094.

- ^ a b Watch Angels, "Waltham: The Timeline, 1850 to 2021," Watch Angels, 2020, p. 12.

- ^ Waltham serial numbers

- ^ Waltham models and grades

- ^ Waltham descriptions of observed watches (via Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Waltham Watch Company records," Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Mss:598 1854-1929.

Further reading

- Carosso, Vincent P., The Waltham Watch Company: A Case History, Bulletin of the Business Historical Society, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Dec., 1949), pp. 165–187, published by The President and Fellows of Harvard College

- Engle, Tom; Richard E. Gilbert; and Cooksey Shugart, Complete Guide to Watches, Twenty Seventh Edition, January 2007, ISBN 1-57432-553-1

- Gitelman, H.M., "The Labor Force at Waltham Watch During the Civil War Era," Journal of Economic History, vol. 25, no. 2 (June 1965), pp. 214–243.

- Gitelman, Howard M., Working Men of Waltham: Mobility in American Urban Industrial Development, 1850–1890. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1974.

- Kaplan, Jacob J. et al., "The Reorganization of the Waltham Watch Company: A Clinical Study," Harvard Law Review, vol. 64, no. 8. (June 1951), pp. 1252–1286.

- Marsh, Edward A. The Evolution of Automatic Machinery as Applied to the Manufacture of Watches at Walthamm Mass, by the American Watch Co., Chicago: G. K. Hazlitt & Co., 1896.

- Moore, C.W., "Some Thoughts on the Early Labor Policy of the Waltham Watch Co.," Bulletin of the Business Historical Society, vol. 13, no. 2 (April 1939), pp. 25–29.

- Moore, Charles W., Timing a Century: History of the Waltham Watch Company. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1945.

- Shugart, Cooksey, The Complete Guide to American Pocket Watches, 1981, ISBN 0-517-54378-8

External links

- Official Waltham Watches Website

- Jonathan A. Boschen, "Waltham's Watches," (documentary video) Jonathan A. Boschen Motion Pictures, via YouTube, 2011.

- Waltham Watch Company Records at Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School

- Extensive collection of Waltham pocket watches

- Waltham Aircraft Clock Corporation website.

- NAWCC: National Association of Watch & Clocks Collectors

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Articles with short description

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2017

- AC with 0 elements

- 1850 establishments in Massachusetts

- Buildings and structures in Waltham, Massachusetts

- Clock manufacturing companies of the United States

- Watch manufacturing companies of the United States

- Manufacturing companies established in 1850

- Waltham, Massachusetts