1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera

| 1886 Eruption of Mount Tarawera | |

|---|---|

Mount Tarawera in Eruption by Charles Blomfield | |

| Volcano | Mount Tarawera |

| Start date | 10 June 1886 |

| Start time | 2 a.m. |

| End date | 10 June 1886 |

| End time | 8 a.m. |

| Type | Plinian, Peléan |

| Location | North Island, New Zealand 38°13′0″S 176°31′0″E / 38.21667°S 176.51667°E |

| VEI | 5 |

| Impact | ca. 120 killed,[1] Pink and White Terraces destroyed, formation of Waimangu Volcanic Rift Valley, enlargement of Lake Rotomahana |

Location of Mount Tarawera | |

In 1886, a violent eruption occurred at Mount Tarawera, near the city of Rotorua on New Zealand's North Island. At an estimated Volcanic Explosivity Index of 5, the eruption is the largest and deadliest in New Zealand during the past 500 years, which includes the entirety of European history in New Zealand.[2] The eruption began in the early hours of 10 June 1886 and lasted for approximately 6 hours, causing a 10-kilometre-high (6.2 mi) ash column, earthquakes, lightning, and explosions to be heard as far away as Blenheim in the South Island — more than 500 kilometers (300 miles) away. A 17-kilometre-long (11 mi) rift formed across the mountain and surrounding area during the eruption, starting from the Wahanga peak at the mountain's northern end and extending in a southwesterly direction, through Lake Rotomahana and forming the Waimangu Volcanic Rift Valley.

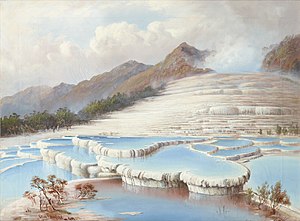

Damage in the local area was extensive, with ash fall blanketing nearby villages including Te Wairoa.[1] The eruption is responsible for the presumed destruction of the famed Pink and White Terraces, which prior to the eruption were New Zealand's most famous tourist attraction and brought visitors from across the British empire.[3] Lake Rotomahana, the former site of the terraces, significantly expanded as a result of the eruption as it filled portions of the newly-formed rift valley.[4]

At the time of the eruption, around 150 people were believed to have died. Modern estimates however have revised this down to around 120, with the majority of deaths coming from Māori villages near the mountain.[1] As such, the eruption is the deadliest known in New Zealand history, although the lahar-caused Tangiwai disaster from 1953 has a higher overall death count.[5]

Geology

Mount Tarawera is a rhyolitic dome volcano that makes up part of the Ōkataina Volcanic Centre, one of eight caldera systems in the Taupō Volcanic Zone.[6] Other volcanoes which form part of the Ōkataina complex include the Haroharo vents and Lake Rotomā, while the complex also includes geothermal features such as Waiotapu. Mount Tarawera itself reached a height of 1,080 metres (3,540 ft) prior to the eruption, and had three distinct peaks: Wahanga at the north, followed by the highest peak of Ruawahia in the centre, and Tarawera as the southernmost peak. [7] These had been built up by a series of eruptions at Tarawera which first commenced about 18,000 years ago, with the most recent eruption prior to 1886 occurring around 1200 CE.[8]

Prelude

The months prior to the eruption saw an increase in geothermal activity in the region, particularly through increased discharge at nearby hot springs and geysers.[9] In the days leading up to the eruption, a series of unusual events were documented by those living in or visiting the area. On 31 May, 11 days prior to the eruption, a group of tourists returning from the Terraces claimed to have seen a war canoe approaching their boat before disappearing into the mist. Witnesses described two rows of occupants, one of which was "standing wrapped in flax robes, their heads bowed and, according to Māori eyewitnesses, their hair plumed as for death" using huia and kōtuku feathers.[10] Tūhoto Ariki, a tohunga at Te Wairoa, declared that the tourists had sighted a waka wairua (spirit canoe) which was to herald the destruction of the region.[11]

In the days between the apparent sighting of the waka and the eruption, further signs of unrest were noted. In one account from Sophia Hinerangi, a renowned Māori guide in the area, her tour party found the creek in which the boats were moored was dry, with the boats beached in the mud. A series of seiches then occurred, flooding the creek with lake water before receding again.[11] On other instances the dock would suddenly flood while the tour party was waiting, leading to local guides refusing to go on the lake without persuasion.[10] These phenomena were collectively interpreted by a local Māori chief as heralding an impending war, while Tūhoto Ariki saw them as consistent with his interpretation of the waka wairua.[11]

Eruption

Shortly after midnight on the morning of 10 June 1886, a series of more than 30 increasingly strong earthquakes were felt in the Rotorua area[12] and an unusual sheet lightning display was observed from the direction of Tarawera. Explosions began at around 1:30am, with a larger earthquake at around 2:10 am being followed by the formation of an eruption cloud roughly 9.5 kilometres (5.9 mi) high.[9][13][14] During this initial phase, an 8-kilometre-long (5.0 mi) fissure vent opened from the Wahanga dome initially to extend across Mount Tarawera itself, causing fountains of semi-basic andesitic lava.[15] By 2:30 am, all three of Mount Tarawera's peaks had erupted, blasting three distinct columns of smoke and ash thousands of metres into the sky.[16] The fissure continued to expand to the southwest as the eruption progressed, at the same time as eruptive activity was increasing around the present location of Waimangu.[9]

At around 3.30 am, the largest phase of the eruption commenced when the expanding rift reached Lake Rotomahana, causing the lake water to come into contact with magma and resulting in a large explosion and a volcanic crater two kilometres wide at the former site of the lake.[15] This explosion distributed a mix of wet ash and lapilli over an area of 10,000 square kilometres (3,900 sq mi) and produced a pyroclastic surge which destroyed several villages within a 6-kilometre (3.7 mi) radius, causing the majority of deaths associated with the eruption.[9] Ash fall of up to 15 metres (49 ft) was reported in the immediate vicinity of the rift, while a layer of ash 8-10 centimetres deep fell on Te Puke and lighter amounts were reported on boats in the Bay of Plenty up to 240 kilometres (150 mi) to the north.[15][11] This stage of the eruption saw a dramatic increase in the height of the eruption column, with estimates placing the height at between 27.8 kilometres (17.3 mi) and 34 kilometres (21 mi) in order to produce the pattern of ash observed given weather conditions.[14][9] The effects of this ash were seen from as far south as Christchurch, over 800 kilometres (500 mi) away.[11] Approximately 2 cubic kilometres (0.5 cubic miles) of tephra was erupted,[17] more than Mount St. Helens ejected in 1980.

This phase of the eruption continued for less than three hours, with the majority of the eruption having stopped by 6:00 am. Ash fall continued to occur in surrounding areas and as far away as Tauranga, prompting city officials to consider the evacuation of the city.[11] Material continued to be ejected from craters at Rotomahana and Okaro for up to ten days after the initial eruption, although these declined in frequency and intensity.[18] Occasional phreatic eruptions continued to occur at Rotomahana for months after the initial eruption, before declining volcanic activity allowed the former lake to begin refilling.[15]

The noise from this eruption was reported across the country, from as far away as Kaikōura, where it was thought to be a ship in distress, and Blenheim, where the shock-wave rattled windows. Māori on the Whanganui River believed the noise to be from an approaching war party, while in Auckland the noise and sight of the eruption was thought by some to be an attack by Russian warships.[11]

Casualties

At the time of the eruption, the official death toll was 153 – consisting mostly of Māori who lived in villages near the volcano. However, more recent research by physicist Ron Keam has only identified 108 people killed by the eruption. Much of the discrepancy was due to misspelled names and other duplications. Allowing for some unnamed and unknown victims, he estimated that the true death toll was 120 at most.[13][19] This is disputed by local iwi, with oral accounts fron Ngāti Hinemihi stating a death toll of thousands.[20]

The Māori settlements of Moura, Te Koutu, Kokotaia, Piripai, Pukekiore, Otuapane, Te Tapahoro, Te Wairoa, Totarariki, and Waingongoro were buried or destroyed. Beyond the official death toll, many survivors of the eruption from these villages were displaced, with several (including Sophia Hinerangi) moving to nearby towns such as Whakarewarewa or Rotorua.[2] Some of the local survivors at Te Wairoa took shelter in a Māori meeting house, a wharenui, named Hinemihi, which was later taken to England and erected in the grounds of Clandon Park, the seat of the 4th Earl Onslow, who had been governor-general of New Zealand at the time.

Te Wairoa is now a tourist attraction called "The Buried Village". Many people survived by sheltering in Te Wairoa's stronger buildings.[1]

Effects

The eruption left the area immediately around the volcano covered by a thick layer of volcanic ash, mud and debris – in some places up to 20 metres (66 ft) thick.[21] Forests in the area, which before the eruption featured a wide variety of native trees including rimu, rata, tōtara, and pōhutukawa, were devastated, with the first two of these disappearing completely from Tikitapu forest, to Tarawera's west.[22] In contrast to the devastation in Tikitapu forest, forests on Putauaki many of the larger trees survived, despite 36 centimetres (14 in) of ash falling at that mountain. This difference appears to be due to slight differences in the type of ash which fell in each place: at Tikitapu, the ash was moist and mud-like, while that which fell at Putauaki was dryer and primarily scoria.[22] Other vegetation in the same direction as Putauaki also emerged largely unscathed, despite 60 centimetres (24 in) of ash falling in many places. Forests on Tarawera itself, which were extensive prior to the eruption, were completely destroyed.[23] Accounts from the aftermath describe the forest as "a mass of broken limbs and riven stumps, wrenched and torn to an extent that renders the wood utterly useless."[22]

Ash continued to dominate the landscape for years following the eruption. Rapid erosion caused the formation of steep v-shaped ridges and valleys in the deepest areas of ash fall, providing scientists with a cross-section of the eruption phases.[15] While forest regeneration did occur, this happened at different paces in different locations. This initially included plants such as bracken, tutu, and tree ferns, as well as introduced species such as the blue gum and prickly acacia, but later began to include traditional species such as pōhutukawa, kamahi and rewarewa.[15][22] Most notably, the large amount of ash and other volcanic material blocked Kaiwaka stream, which previously had drained Lake Rotomahana into nearby Lake Tarawera. The resulting blockage significantly increased the size of Lake Rotomahana, causing the lake level to rise and fill the eruption craters to eventually reach 60 metres (200 ft) above its pre-eruption level.[24]

The opening of a 17-kilometre-long (11 mi) rift from the summit of Tarawera through to the southwest also significantly changed the landscape. The southern end of this rift became known as the Waimangu Volcanic Rift Valley, and included a range of new geothermal systems formed in the aftermath of the eruption. The area takes its name from the Waimangu Geyser, which erupted between 1900 and 1908 at heights of up to 460 metres (1,510 ft), making it the most powerful geyser in the world.[25]

Pink and White Terraces

Most famously, the eruption was long believed to have caused the destruction of the Pink and White Terraces, New Zealand's greatest tourist attraction at the time. The terraces, which prior to the eruption sat on the shoreline of Lake Rotomahana, could not be found in the new landscape after the eruption and were presumed lost due to the devastation across the rest of the area. Accounts from the time describe the devastation around where Rotomahana had erupted, with a large crater on the site of the White Terraces and the Pink Terraces "having been blown away".[18] Guides in the area explored the new landscape for any sign of the terraces, refusing to believe that they had been destroyed despite a lack of evidence as to their survival.[26]

However, in 2011, portions of both the Pink Terraces and later the White Terraces were rediscovered some 60 metres below the current level of Lake Rotomahana by scientists from New Zealand's GNS Science.[27][28] The announcement of the rediscovery of the White Terraces coincided with the 125th anniversary of the eruption. The exact location and extent of the terraces continues to be the subject of much research, with a 2017 study using a forgotten 1859 survey to suggest possible locations of the Pink and White Terraces and map the extent of the original Lake Rotomahana.[29][30][31][32]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Eruption of Mt Tarawera". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Okataina Volcanic Centre/ Mt Tarawera Volcano / New Zealand Volcanoes / Volcanoes / Science Topics / Learning / Home - GNS Science". www.gns.cri.nz. GNS Science Te Pū Ao. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Pink and White Terraces". Rotorua Museum. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Background Info / Rotomahana project / Volcanoes / Science Topics / Learning / Home - GNS Science". www.gns.cri.nz. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Tangiwai railway disaster". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Cole, J. W.; Deering, C. D.; Burt, R. M.; Sewell, S.; Shane, P. A. R.; Matthews, N. E. (1 January 2014). "Okataina Volcanic Centre, Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand: A review of volcanism and synchronous pluton development in an active, dominantly silicic caldera system". Earth-Science Reviews. 128: 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.10.008. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Other events and outcomes". Christchurch Libraries.

- ^ Nairn, I.A. "Volcanic hazards at Okataina Centre". gns.cri.nz. Palmerston North: Ministry of Civil Defence. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Sable, J.E.; Houghton, B.F.; Wilson, C.J.N.; Carey, R.J. (2009). Thordarson, Thor (ed.). Studies in Volcanology: The Legacy of George Walker. London: The Geological Society. ISBN 978-1-86239-280-9.

- ^ a b McLintock, Alexander Hare; Jones, Ronald. "TARAWERA, PHANTOM CANOE". An encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, 1966. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu Taonga. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yarwood, Vaughan. "The night Tarawera awoke". New Zealand Geographic. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "On this day: Tarawera volcanic eruption in 1886". New Zealand Earthquake Commission. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ a b R. F. Keam (1988). Tarawera. ISBN 978-0-473-00444-6.

- ^ a b Walker, George P.L.; Self, Stephen; Wilson, Lionel (June 1984). "Tarawera 1886, New Zealand — A basaltic plinian fissure eruption". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 21 (1–2): 61–78. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(84)90016-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Park, James (1911). "Tarawera Eruption and after". The Geographical Journal. 37 (1): 42–49. doi:10.2307/1777578. ISSN 0016-7398.

- ^ "Mt Tarawera eruption 125th anniversary". Department of Conservation, Government of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ "Okataina: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ a b Hutton, F. W. (1 January 1887). "The Eruption of Mount Tarawera". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 43 (1–4): 178–189. doi:10.1144/gsl.jgs.1887.043.01-04.16. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Aftermath – Death list Archived 4 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Anheizen.com. Accessed 20 March 2009.

- ^ In 2007, the General Manager of the Earthquake Commission said that "... Ngati Hinemihi oral accounts put the death toll in the thousands." David Middleton (2007). A Roof Over Their Heads? The challenge of accommodation following disasters Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 12 April 2008.

- ^ "Waimangu: Geology". GNS Science. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d Nicholls, J.L. (1939). "The Volcanic Eruptions of Mt. Tarawera and Lake Rotomahana and Effects on Surrounding Forests" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Forestry: 133–142. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Aston, B. C. (1916). "The Vegetation of the Tarawera Mountain, New Zealand: Part I. The North-West Face". Journal of Ecology. 4 (1): 18–26. doi:10.2307/2255447. ISSN 0022-0477. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Daly, Michael (17 March 2021). "New map of Lake Rotomahana lakefloor shows likely locations of Pink and White Terrace remnants". Stuff. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "The Waimangu Geyser". Waimangu Volcanic Valley. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Keam, R.F. (1993). "Warbrick, Alfred Patchett". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "Scientists find part of Pink and White Terraces under Lake Rotomahana". GNS Science. 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011.

- ^ Cherie Winner (9 May 2012). "In Search of the Pink and White Terraces". Oceanus Magazine. Vol. 49, no. 2. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. ISSN 1559-1263. Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Bunn, Rex; Nolden, Sascha (7 June 2017). "Forensic cartography with Hochstetter's 1859 Pink and White Terraces survey: Te Otukapuarangi and Te Tarata". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 48: 39–56. doi:10.1080/03036758.2017.1329748. ISSN 0303-6758. S2CID 134907436.

- ^ Bunn and Nolden, Rex and Sascha (December 2016). "Te Tarata and Te Otukapuarangi: Reverse engineering Hochstetter's Lake Rotomahana Survey to map the Pink and White Terrace locations". Journal of New Zealand Studies. NS23: 37–53.

- ^ Bunn, Rex; Nolden, Sascha (7 June 2017). "Forensic cartography with Hochstetter's 1859 Pink and White Terraces survey: Te Otukapuarangi and Te Tarata". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 48: 39–56. doi:10.1080/03036758.2017.1329748. ISSN 0303-6758. S2CID 134907436.

- ^ Bunn and Nolden, Rex and Sascha (December 2016). "Te Tarata and Te Otukapuarangi: Reverse engineering Hochstetter's Lake Rotomahana Survey to map the Pink and White Terrace locations". Journal of New Zealand Studies. NS23: 37–53.

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Use dmy dates from October 2019

- Infobox mapframe without OSM relation ID on Wikidata

- 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera

- 19th-century volcanic events

- History of New Zealand

- 1886 natural disasters

- Volcanic eruptions in New Zealand

- June 1886 events

- VEI-5 eruptions

- Plinian eruptions

- Peléan eruptions

- Taupō Volcanic Zone

- Pages using the Kartographer extension